Abstract

Purpose: We provide an overview of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) efficacy for adult alcohol or other drug use disorders (AOD) and consider some key variations in application as well as contextual (ie, moderators) or mechanistic (ie, mediators) factors related to intervention outcomes.

Methods: This work is a narrative overview of the review literature on CBT for AOD.

Results: Robust evidence suggests the efficacy of classical/traditional CBT compared to minimal and usual care control conditions. CBT combined with another evidence-based treatment such as Motivational Interviewing, Contingency Management, or pharmacotherapy is also efficacious compared to minimal and usual care control conditions, but no form of CBT consistently demonstrates efficacy compared to other empirically-supported modalities. CBT and integrative forms of CBT have potential for flexible application such as use in a digital format. Data on mechanisms of action, however, are quite limited and this is despite preliminary evidence that shows that CBT effect sizes on mechanistic outcomes (ie, secondary measures of psychosocial adjustment) are moderate and typically larger than those for AOD use.

Conclusion: CBT for AOD is a well-established intervention with demonstrated efficacy, effect sizes are in the small-to-moderate range, and there is potential for tailoring given the modular format of the intervention. Future work should consider mechanisms of CBT efficacy and key conditions for dissemination and implementation with fidelity.

Introduction

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for alcohol and other drug use disorders (AOD) is one of the most widely studied modalities of addiction treatment in the United States and internationally. In 1985, Marlatt and Gordon published their seminal work on Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, which can be considered the “blueprint” for CBT treatment for addiction.1 Other key publications during this time include Daley’s2 Relapse Prevention Workbook: For Recovering Alcohol and Drug Dependence Persons, Monti et a’sl3 Treating Alcohol Dependence: A Coping Skills Training Guide, Kadden et al’s4 Project MATCH Manual for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Carroll’s5 A Cognitive Behavioral Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction. The emergence of CBT for AOD coincided with a broader shift in psychotherapy research toward manualized, empirically-supported treatment, and an exponential growth in the number of clinical outcome trials testing the efficacy (ie, the effect of intervention compared to one or more types of experimental control conditions) of specific-modality interventions for a range of mental health conditions. As a result, CBT for AOD has an extensive empirical base and is featured in a number of practice guidelines such as those from United States’ Department of Health and Human Services6 and the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Care Excellence.7 A survey of US treatment facilities shows 96% of program administrators report use of relapse prevention and 94% report use of CBT, and these percentiles are second only to the reported use of “drug counseling”.8 In short, the presence of CBT for AOD in the treatment landscape can be considered ubiquitous.

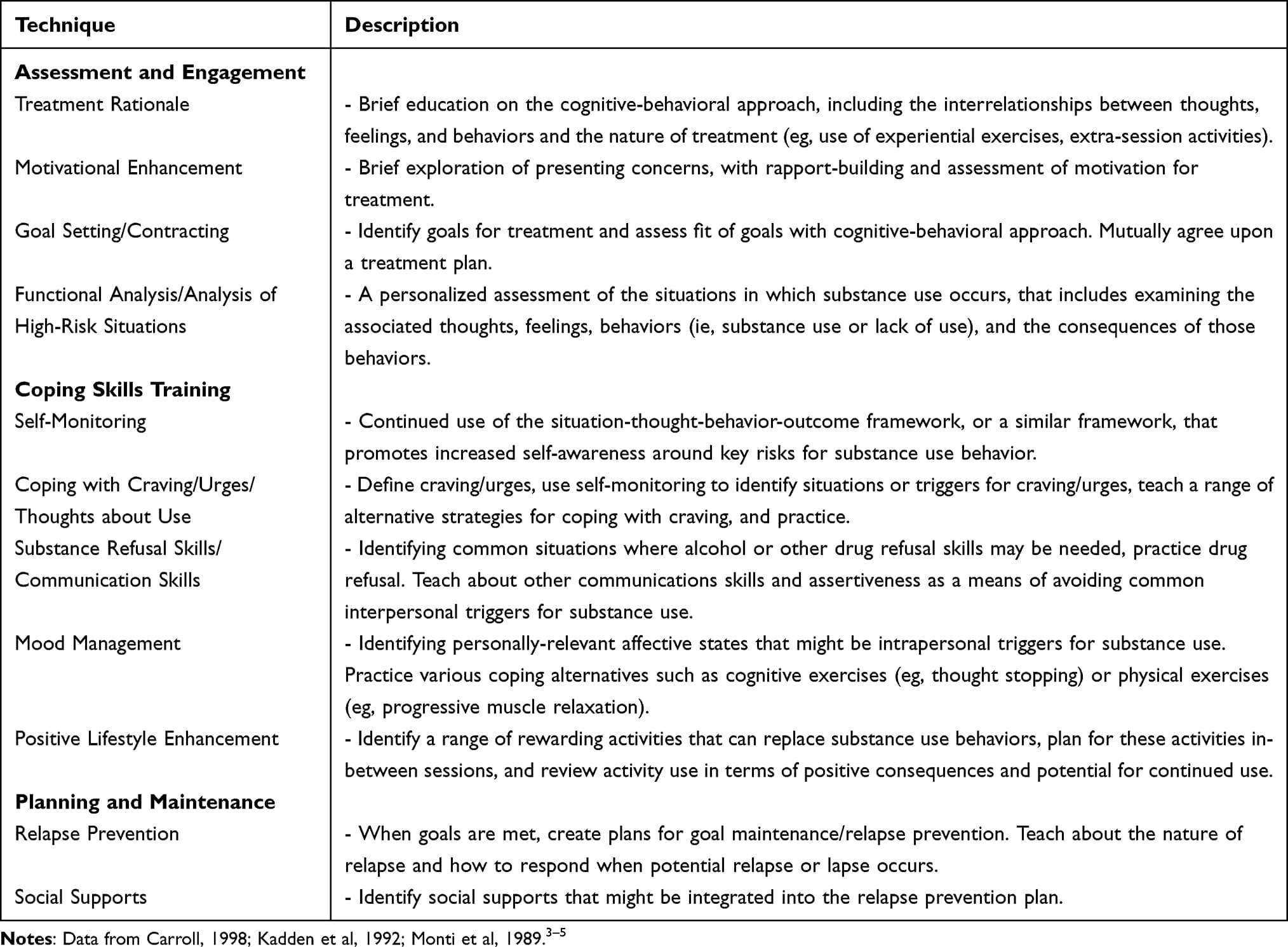

The question of whether one has heard of CBT might be relatively straightforward to answer, but what defines CBT is more challenging. Given its ubiquity and longevity, CBT for addiction is increasingly becoming an umbrella term for interventions that include a range of cognitive and behavioral techniques (see Table 1). For the purposes of the present discussion, we define CBT for AOD as a class of interventions that are time-limited, targeted, and based on principles of both cognitive (ie, an emphasis on the role of thoughts in shaping emotions and behaviors) and behavioral (ie, an emphasis on the role of behaviors in shaping emotions and thoughts) therapies. There is typically a phase of personalized assessment characterized by techniques such as functional analysis. Then, there is a phase of action, or coping skills training, that emphasizes enactment of specific behaviors to re-shape reward contingencies, put numerous biopsychosocial resources into place, and facilitate ongoing relapse prevention given this can be part of the normal course of AOD.

Table 1 Techniques Often Used in CBT for AOD, by Treatment Phase

Part of the difficulty in defining CBT is its evolution and diffusion. According to Hayes, three waves of behavioral therapies can be identified, beginning in the purest sense with the application of classical and operant conditioning principles to change specific behaviors.9,10 In the second wave, the integration of cognitive principles occurred via the work of Beck11 and Ellis12 and the integration of social-cognitive principles via the work of Bandura.13 The third wave characterizes even further integration with relational and humanistic principles, as well as spiritual and meditation practices which resulted in new forms of CBT not named as such, but with many shared theoretical underpinnings, processes, and techniques (eg, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Dialectical Behavior Therapy; Mindfulness-based Relapse Prevention).14–16 The literature has also seen increasing specific-modality therapies being combined with CBT, such as adding Motivational Interviewing (MI) or Contingency Management (CM). Modern day CBT for addiction is decidedly integrative and increasingly so as the applications evolve to reach novel and understudied populations.

Purpose and Aims

In the present narrative review, we offer an overview of CBT efficacy for adult AOD and consider some key variations in application as well as contextual (ie, moderators) or mechanistic (ie, mediators) factors related to intervention effectiveness. Specifically, we will examine what might be considered “classical” or “traditional” applications based on Marlatt and Gordon’s17 seminal work but will also consider some integrative applications such as CBT in combination with MI, CM, and pharmacotherapy. Next, we will review novel extensions such as digital format CBT. Finally, we will examine moderating and mediating factors that have been observed in studies of intervention efficacy. This work is intended to be a user-friendly overview of a large literature. As such, we provide a summary of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, but some landmark trials are also described. The population focus is adults with a diagnosed alcohol or other drug use disorder, as well as adults with substance use that may place them a risk for related consequences. To add clinical utility to this review, effect size data will be summarized using Cohen’s generic benchmarks of “small” (d ~ 0.20), “medium” (d ~ 0.50), and “large” (d ~ 0.80).18 In discussion, we provide final remarks on for whom, how, and where CBT may work best.

Results

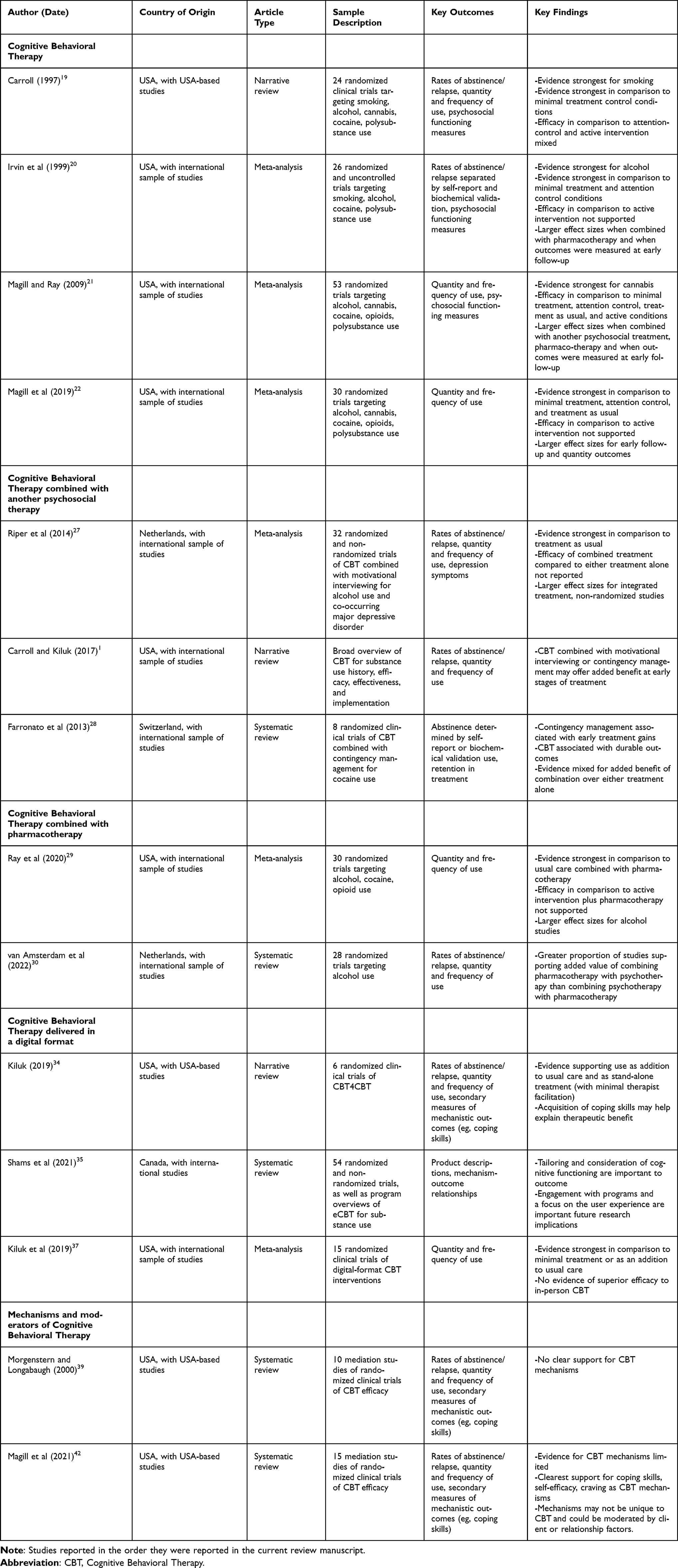

See Table 2 for a list and description of the studies reviewed in the following subsections.

Table 2 Reviews of CBT Efficacy for AOD

Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

In review studies of CBT for AOD, some general conclusions can be reached not only about intervention efficacy, but also about key outcomes and areas for future study. An early narrative review of 24 studies concluded CBT’s general efficacy compared to no-treatment controls (ie, waitlist), mixed evidence regarding superiority over usual care or other time and attention matched comparators (ie, attention-placebo), and absent evidence that it was more efficacious than another “active”, empirically-supported treatment.19 In 1999, Irvin et al completed the first meta-analysis of relapse prevention with the intention of directly following up on this earlier work. Here, 26 studies were reviewed across substances, including smoking, and both substance use and psychosocial outcomes were examined. The review mostly confirmed earlier conclusions regarding comparative efficacy over different levels of experimental control (ie, no treatment, attention-placebo, active treatment), although no studies in the sample contrasted CBT with usual, community care. The study also observed larger effect sizes in alcohol studies, at early follow-up, and for outcomes other than substance use such as self-efficacy, coping skills, and indicators of psychosocial adjustment (eg, depression symptoms).20More recent meta-analyses have demonstrated similar results with some exceptions. In a 2009 meta-analysis, 53 randomized clinical trials were reviewed, and CBT demonstrated efficacy over all levels of comparator, with effect sizes that were relative to the strength of each type of experimental control.21 In other words, effects were largest when CBT was compared to no treatment (kes = 6), while attention-placebo, usual care, and active comparison effect sizes were typically small (kes = 49). A 2019 meta-analysis of 30 clinical trials showed similar results although the effect size across active comparator studies (kes = 17) was non-significant.22 This raises a key point, which is that it is difficult to obtain a clinically-meaningful measure of CBT effect from the narrative review and meta-analytic literature because of the relative rarity of waitlist-controlled trials. The bar for demonstrated efficacy is quite high, and measures of how effective CBT is (ie, how much change is expected relative to baseline) are not typically provided. Therefore, it can be concluded that CBT is efficacious and the evidence is robust with respect to no treatment, attention-placebo, and even usual care, but how strong the effect is and for what outcomes is another question.How much change can a clinician, patient, or family expect from an evidence-based intervention, is a question of clinical significance. In Project MATCH, the US patient-to-treatment matching trial targeting alcohol use disorder, baseline to 15-month follow-up effect sizes for the CBT condition were d = 1.46 (r = 0.59) for the percentage of days abstinent and d = 1.61 (r = 0.62) for the number of drinks per drinking day, which are clinically meaningful improvements on average. Outcomes could additionally be classed by abstinence (25% of participants in the outpatient arm; 48% of participants in the aftercare arm) and continued use without associated consequences (7% of participants in the outpatient arm, 14% of participants in the aftercare arm).23 In our previously noted review in 2019, effect sizes did not significantly differ between alcohol studies and studies of one or more illicit drugs, but this latter group was heterogenous including studies of opioid use, stimulant use, and poly substance use.22 It is also noteworthy that Irvin et al observed significantly higher effect sizes for psychosocial outcomes compared to outcomes based on frequency or quantity of substance use.20 To our knowledge, that was the last published meta-analysis to consider these secondary measures of clinical benefit, and given recent dialog around what constitutes an optimal outcome metric in addiction research24,25 as well as interest in operationalizing the construct of recovery as beyond and not requiring abstinence,26 this is a limitation of the current literature review. In Project MATCH, 15-month follow-up effect sizes for secondary outcomes such as reduced psychiatric severity (d = 0.39/ r = 0.19) and alcohol-related consequences (d = 1.5/ r = 0.60) were moderate to large, respectively.23Summary. CBT for AOD is efficacious compared to no-treatment, attention-placebo, and usual care control conditions, but not compared to other evidence-based interventions such as CM or MET. Data on CBT effects for use outcomes by primary substance provide a mixed picture, and at present, most trials have targeted alcohol use disorder. Within condition, baseline-to-follow-up, effect sizes are not available at the aggregate level, but large-scale alcohol trial data show clinically meaningful change in frequency and quantity of use as well as psychosocial adjustment associated with CBT.

Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Combined with Another Psychosocial Treatment

In the most recent meta-analysis that examined CBT combined with another psychosocial treatment, Magill and Ray found a pooled effect size (across levels of experimental control, kes = 19) roughly double that of studies testing CBT alone (kes = 21).21 The added psychosocial treatments included MI and CM. When combining CBT with MI specifically, the expectation would be that the MI condition could be used as a pre-treatment to promote engagement in a subsequent course of CBT or integrated into the CBT protocol to incorporate additional relational and motivational elements throughout the course of care. Unfortunately, we are not aware of reviews that have examined the optimal timing and mode of integration when CBT and MI are combined. In a meta-analysis of 32 studies that examined alcohol consumption and co-occurring depression specifically, the combination was superior to usual care and brief intervention controls with effect sizes in the small-to-moderate range, but data on comparative efficacy compared to either treatment alone were not presented.27 For CBT combined with CM, the expectation is that CM could enhance compliance with prescribed CBT activities and that CBT could promote maintenance of early treatment gains due to the use of contingent reinforcers for abstinence. Narrative reviews have suggested support for this proposed benefit across four studies with individuals using cocaine (k = 2) or cannabis (k = 2).1 A systematic review of eight studies specifically targeting cocaine use found CM indeed produced earlier treatment gains and that CBT effects were more durable, but support for an additive effect for one treatment compared to the other was mixed with 2 out of 5 studies demonstrating this conclusion.28Summary. In early review, a robust benefit of combined CBT with other psychosocial therapies such as MI and CM was observed. However, this effect tends to be in contrast to minimal treatment and usual care. These effects have been observed in trials targeting alcohol use with co-occurring depression, cannabis use, and cocaine use. However, the additive effect of these combined interventions, despite clinically intuitive expectations of their compatibility, and even synergy, has not received conclusive support.

Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Combined with Pharmacotherapy

Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and large-scale trials of CBT combined with some form of pharmacotherapy provide data on efficacy, but much less is known about CBT combined with a specific therapeutic drug. For both the Irvin et al20 and Magill and Ray21 meta-analyses, observed effect sizes were larger for combined CBT and pharmacotherapy than for CBT delivered alone. In a meta-analysis addressing CBT combined with pharmacotherapy, 30 randomized clinical trials targeted alcohol (50%), cocaine (23%), and opioids (20%), and the following were the most common pharmacotherapies tested - naltrexone hydrochloride and/or acamprosate calcium (42%), methadone hydrochloride or combined buprenorphine hydrochloride and naltrexone (18%), and disulfiram (8%).29 Across the sample, the most conclusive support was for combined CBT and pharmacotherapy in contrast to usual, medication management and pharmacotherapy. Here, the effect size for posttreatment consumption frequency was small (kes = 9) but was more moderate for consumption quantity (kes = 3). CBT and pharmacotherapy compared to another active treatment (ie, MI or CM) and pharmacotherapy showed a non-significant pooled effect size. Results at later follow-ups were less conclusive, and the majority of trials did not report follow-up data.29A recent systematic review of 28 studies was concerned specifically with the question of whether CBT for alcohol use disorder combined with pharmacotherapy was better than CBT alone or pharmacotherapy alone.30 A note of caution here is that the authors included some MI studies in this work on CBT. In a “box-score” review (ie, a review with conclusions guided by statistical significance tests), the authors found that adding pharmacotherapy to CBT or MI was beneficial in 53% of the trials reviewed (k = 19). In contrast, combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was beneficial compared to pharmacotherapy alone in 33% of the trials reviewed (k = 9). Thus, the conclusion was that there was additional value particularly when adding pharmacotherapy to CBT delivery. This pattern of benefit, however, was not observed in the landmark US study Project COMBINE.31 Patients receiving weekly medication management with naltrexone or cognitive-behavioral intervention (CBI; ie, a combined MI and CBT condition) showed the highest abstinence rates (ie, 80% days abstinent), but the interaction did not show statistically significant efficacy comared to either treatment alone (ie, 76% days abstinent).31Summary. The literature provides a somewhat complex narrative on the efficacy of combined CBT and pharmacotherapy. In the largest trial to date, the added benefit of the combination was not observed, but review data suggest some benefit, and particularly for adding pharmacotherapy to CBT for alcohol use disorder. Meta-analytic data also suggest that when choosing between medication management and a more comprehensive adjunct to pharmacotherapy, the more comprehensive intervention is preferred. Finally, summary data on individual drugs beyond alcohol, later follow-up outcomes, and secondary measures of psychosocial functioning are quite sparse.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Delivered in a Digital Format

Interest in digital interventions (ie, delivered through a digital platform such as smartphone applications, tablets, or computers) has been on the rise for the last two decades. This is for several reasons including, the potential for cost-efficiency, the potential to reach individuals who are not inclined toward or do not have access to face-to-face therapy, and most recently, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic that shifted much of daily life activities to an online format. Digital interventions can include interactive teaching features and behavioral monitoring, making them highly conducive for CBT interventions. These interventions can be used as “clinician extenders” or as alternatives to traditional face-to-face therapy32 and may hold particular promise in medical or other non-specialty care settings where the opportunity for early intervention is high yet available resources for that intervention are low.33 Moreover, there is a health equity potential to these interventions because access in underserved geographic areas is possible and barriers due to stigma can be reduced or eliminated due to capacity for anonymous usage.34,35 At the same time, poor digital-health literacy, internet access limitations, and wariness of new technologies can be obstacles to broad access and implementation of digital interventions.36A recent meta-analysis by Kiluk et al studied 15 clinical trials of technology-based CBT interventions for alcohol use.37 The studies reviewed tended to include large samples (>500 participants), were conducted with individuals using alcohol that were non-dependent (95%), and most of the interventions explicitly targeted moderation (60%). These programs were delivered via internet-based websites or software programs and were self-directed with CBT as well as MI-based content. When delivered as stand-alone interventions and contrasted with minimal treatment controls, these programs showed small effect sizes (kes = 5) and non-significant effects compared to usual care (kes = 2). When delivered as an addition to usual care, however, the effect size was moderate (kes = 7) and stable over 12-month follow-up. There were only a few studies that compared digital CBT to in-person CBT, and this pooled effect size was non-significant (kes = 2).Summary. The literature available on digital CBT suggests these interventions have strong potential for reach (based on the large number of participants treated compared to studies of in-person CBT) and that they are efficacious as stand-alone treatments and as clinician-extenders in the context of usual care. However, the review data on drugs other than alcohol are quite limited, although studies of specific programs (eg, CBT4CBT; Computer-Based Training for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, TES; Therapeutic Education System) have been conducted. These interventions are also often integrative and may target additional outcomes such as depression (eg, SHADE: Self-Help for Alcohol and Other Drug Use and Depression). Additional studies or an updated review may shed light on moderators of efficacy and particularly those that could inform product design (eg, access point, esthetics, dosage, degree of clinician involvement) to optimize impact.

How and for Whom Does Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for AOD Work?

Mechanisms of behavior change (MOBC) are person-level processes that exert a causal influence on a specific behavior change outcome. MOBC can be in relation to naturalistic change or treatment-facilitated change and there may be a set of core underlying mechanisms relevant to many types of behavior change outcomes (eg, self-regulation, stress reactivity/resilience, social processes).38 MOBC research emphasizes the question of how change occurs (eg, statistical mediators of intervention efficacy or effectiveness) and part of identifying how, might require answering questions of for whom an intervention is effective (eg, statistical moderators of intervention efficacy or effectiveness). For CBT for AOD, the MOBC of interest are the specific indicators that are, based in theory, expected to transmit the effects of the intervention on its targeted outcomes. These include cognitive shifts in self-efficacy related to various risk scenarios (eg, negative affective states, positive affective states), enactment of coping skills relevant to the CBT approach (eg, quantity or quality of skills), changes to environmental contingencies (eg, quantity or quality of available social supports). If CBT is delivered in an integrated format, then additional MOBC relevant to the other intervention should be considered.Despite the richness of its theoretical foundations, the literature thus far has not provided a clear picture of how CBT exerts its effects on AOD outcomes. In an early systematic review by Morgenstern and Longabaugh, ten secondary, mediation analyses of CBT clinical trials were reviewed and the authors concluded that there was very little support for purported mediators of CBT effects.39 This was partly due to an absence of tests of the full path model (ie, CBT condition to a purported mediator/s [a path] and the purported mediator/s to outcome [b path]), and when such tests were conducted, there were only two instances of support (ie, indicators of coping skill in relation to cannabis use outcomes).40,41 In a follow-up systematic review,42 the pool of available studies went from 10 to 15, and six of the 15 studies were based on data from either Project MATCH23 or Project COMBINE.31 Half of studies targeted alcohol use (50%), and the second largest group of studies targeted polydrug use (40%). The authors summarized the selection of potential mediators as related to self-efficacy, copings skills, craving/affect regulation/stress, and other (eg, social measures as well as more generalist constructs such as the therapeutic alliance). The mediation studies were additionally grouped by whether the independent variable was a between (ie, CBT versus another treatment) or within (ie, a CBT-related process) condition indicator.The 2020 systematic review42 provided conclusions only somewhat more informative than the systematic review conducted 10 years earlier.39 Specifically, there was support for increases in coping skills as a mediator or moderated-mediator in 50% of studies reviewed (k = 8). Self-efficacy, however, was supported in one of seven studies and only when a within-condition, rather than between-condition mediation analysis was conducted. Importantly, between-condition mediation analyses, when supported, can suggest whether the mechanism is uniquely causal to the experimental treatment of interest. Therefore, self-efficacy, an indicator that has shown correlations to outcome in numerous studies (e.g),43 may be a process that is generally related to behavior change rather than specific to CBT. Reduced craving was supported as a mediator of the COMBINE CBI condition in contrast to a minimal treatment control (ie, placebo with medication management). The remaining potential MOBC were a diverse set of theoretically justified constructs with few studies and very little conclusive support. Further, the majority of MOBC models that were supported were conditional upon certain therapeutic conditions (eg, a strong alliance) or patient-characteristics (eg, level of symptom severity or low coping capacity at baseline).42Summary. CBT for AOD has a rich theoretical foundation, including general cognitive and behavioral theories, specific models of CBT for AOD (eg, Marlatt and Gordon’s Relapse Prevention Model), and numerous manuals to facilitate training and delivery with fidelity. In other words, the approach is well-articulated, but despite this, knowledge on MOBC (ie, how it works) and specific matching factors (ie, for whom it works) is limited. The limitations are not in study quality per se, but certainly in study quantity (ie, too few mediation studies to build a cohesive narrative of CBT MOBC) and heterogeneity (ie, varied assessment of potential mediators). This state-of-the-science stands in contrast to a large evidence-base for efficacy across a range of possible implementation conditions (ie, stand-alone, combined with other interventions, delivered in a digital format). From the two review studies considered and the subsequent 15 studies of mediators of CBT effects, coping skills, self-efficacy, and reduced craving show promise, but there is minimal evidence to suggest these processes are uniquely important to CBT and are more likely processes that are broadly relevant to AOD behavior change.

Discussion

This manuscript examined narrative and systematic reviews, large-scale trials, and meta-analyses of CBT for AOD under a range of delivery conditions. From this work, some general conclusions can be reached about intervention efficacy. Consistent with many evidenced-based treatments for addiction, CBT does not produce outcomes that are superior to those achieved by another empirically-supported modality (eg, motivational interviewing, contingency management, twelve step facilitation).20,22,23,29 When compared with usual community care, CBT generally shows superior efficacy with small effect sizes,20–22,29 but the additive benefit of face-to-face CBT combined with usual care has not been established.22 However, given the ubiquity of CBT in US treatment facilities, there may be less of a distinction between CBT and usual care, thus complicating direct tests of added benefit. Other combined interventions such as CBT combined with MI, CM, or a specific pharmacotherapy are also efficacious, but there is mixed evidence to guide exactly how these interventions should be combined to optimize care (eg, sequential, integrated) and data are also mixed regarding whether the combination of interventions is superior to either intervention alone.29–31 When delivered in a digital format, CBT-based interventions have most often targeted alcohol or polysubstance use and have shown significant effects as both a stand-alone treatment and as an addition to community treatment.37Within the CBT for AOD literature, alcohol has been the most studied drug although efficacy for other substances such as cocaine, opioids, and cannabis has been demonstrated in individual trials.1 In the meta-analytic literature, studies with minimal treatment controls (eg, a waitlist, a pamphlet, a very brief intervention) are quite rare and thus effect sizes for CBT are often small. As a result, these metrics of benefit are representative of CBT compared to something else rather than whether this class of interventions is efficacious over a truly inert control condition. Large-scale trials, however, demonstrate meaningful change from baseline with effect sizes in the moderate range (e.g).23,31,44,45 Secondary measures of psychosocial functioning (eg, cognitive changes, mental health and health indicators, quality of life) are typically collected in clinical trials but have not been a focus in the recent CBT for AOD review literature. In early work, these outcomes showed effect sizes nearly double those for substance use, which is important given they may be of equal or even greater importance to stakeholders such as providers, patients, and families.The question of whether a “one-size-fits-all” approach is appropriate is one of dissemination and implementation. In other words, if we know CBT works, what is the version of CBT that should be delivered in community settings? The literature thus far has not pointed to a single version of CBT implementation as superior, and in reality, this has proven an extremely difficult question to answer in the entire field of psychotherapy.46,47 This review has also demonstrated that there is not really one size fits all for CBT. This intervention can be characterized better as a framework for intervention with a core approach that will always be individualized because of an emphasis on functional analysis and/or assessment of high-risk situations that then guide which of a menu of coping skill alternatives will be prioritized over the course of care. According to Carroll and Kiluk, this modularized approach allows for both tailoring and generalization to broader levels of functioning such as other mental health outcomes. For example, in their discussion of CBT4CBT, a given topical module such as coping with craving has clear transdiagnostic implications because the skill being taught is management of uncomfortable stimuli without impulsive responding (ie, emotion regulation).1 Consideration of the adaptability of the core CBT approach must also consider the reality that CBT is now typically integrated with additional treatments to maximize effectiveness. Therefore, there is not one size fits all in relation to CBT, and this is a gift as well as a curse. The gift is the noted adaptability, and the curse is the diffusion of CBT and the possibility that the elements preserved in clinical trials via careful training and monitoring will not be preserved in translation to community care.48 With that said, recent work has suggested feasibility for implementation among community health workers49 and effectiveness of implementation among veteran populations.50

Conclusion

This manuscript offers a narrative overview of CBT efficacy for consideration among researchers, clinicians, and other community stakeholders. This work is an overview and should therefore be viewed as such, as some relevant studies may have been excluded. We provide a broad view and suggest that CBT is efficacious, but given its longevity, it has become increasingly integrative with time. This offers promise with respect to flexibility because there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach. With that said, the priority of the next phase for CBT is implementation and preservation of key elements when adaptation occurs.

Acknowledgment

This research is supported by R01 AA029703 and R21 AA026006 awarded to Molly Magill, K24 AA025704 to Lara A. Ray, and K02 AA027300 awarded to Brian D. Kiluk. This work is supported by funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, although it does not represent official positions of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure

Author Brian Kiluk is a consultant to CBT4CBT, LLC, which makes versions of CBT4CBT available to qualified clinical providers and organizations on a commercial basis. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.