Abstract

We aim to systematically review and meta-analyze the effectiveness and safety of psychedelics [psilocybin, ayahuasca (active component DMT), LSD and MDMA] in treating symptoms of various mental disorders. Web of Science, Embase, EBSCO, and PubMed were searched up to February 2024 and 126 articles were finally included. Results showed that psilocybin has the largest number of articles on treating mood disorders (N = 28), followed by ayahuasca (N = 7) and LSD (N = 6). Overall, psychedelics have therapeutic effects on mental disorders such as depression and anxiety. Specifically, psilocybin (Hedges’ g = -1.49, 95% CI [-1.67, -1.30]) showed the strongest therapeutic effect among four psychedelics, followed by ayahuasca (Hedges’ g = -1.34, 95% CI [-1.86, -0.82]), MDMA (Hedges’ g = -0.83, 95% CI [-1.33, -0.32]), and LSD (Hedges’ g = -0.65, 95% CI [-1.03, -0.27]). A small amount of evidence also supports psychedelics improving tobacco addiction, eating disorders, sleep disorders, borderline personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder. The most common adverse event with psychedelics was headache. Nearly a third of the articles reported that no participants reported lasting adverse effects. Our analyses suggest that psychedelics reduce negative mood, and have potential efficacy in other mental disorders, such as substance-use disorders and PTSD.

1. Introduction

Mental disorders including depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and dementia have an immense toll on the healthcare system and society at large (Brewster et al., 2023). More than 3.5 hundred million people live with depression and 3.74 hundred million people suffer from anxiety disorders globally (Romeo et al., 2020; Zeifman et al., 2021). Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by the persistence of negative thoughts and emotions that disrupt mood, cognition, motivation, and behavior (Vargas et al., 2020). Core features of anxiety disorder include excessive fear and anxiety or avoidance of perceived threats that are persistent and harmful (Kalin, 2020; Penninx et al., 2021). PTSD is a maladaptive and debilitating mental disorder, characterized by re-experiencing, avoidance, negative emotions and thoughts, and hyperarousal in the months and years following exposure to severe trauma (Ressler et al., 2022). At present, there are many treatment measures for patients with depression and anxiety, including drug therapy, evidence-based psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulationtechnology (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021; Penninx et al., 2021). When it comes to the treatment of PTSD, treatments with the strongest support are prolonged behavioral exposure and cognitive processing therapy (Merians et al., 2023). However, even the best-performing drugs and instrumental treatments show modest efficacy, non-negligible side effects, discontinuation problems, and high relapse rates, highlighting the need for novel, improved treatments.

Psychedelics are serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2AR) agonists including lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), ayahuasca (active component N,Nʹ-dimethyltryptamine, DMT),phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (psilocybin) and serotonin transporter (SERT) inhibitor—3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and they have been administered as sacraments since ancient times (Johnson et al., 2019). During the 1950s and 1960s, psychedelics were extensively investigated in psycholytic (low dose) and psychedelic (low to high dose) substance-assisted psychotherapy. Psychedelics can reduce morbidity in patients with various forms of depression and neuroses, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, sexual dysfunctions, and alcohol dependence (Reiff et al., 2020). Current behavioral and neuroimaging data show that psychedelics induce their psychological effects primarily via 5-HT2AR activation and modulate neural circuits involved in mood and affective disorders (Pędzich et al., 2022). Additional findings show that psychedelics enhance glutamate-driven neuroplasticity in animals and may provide a novel mechanism for the lasting symptom improvements observed in recent clinical trials of patients with mental disorders (Aleksandrova and Phillips, 2021).

Although evidence shows that psychedelics have a therapeutic effect on depression, their effectiveness varies across different types of psychedelics. Psilocybin therapy shows antidepressant potential, and Daws assessed the subacute impact of psilocybinon brain function in two clinical trials (an open-label trial and a double-blind phase II randomized controlled trial) of depression. In both trials, the antidepressant effects of psilocybin were rapid and sustained (Daws et al., 2022). The prototypical serotonergic hallucinogen LSD was used in the 1950s-1970s as an adjunct to psychotherapy (Passie et al., 2008). A published study showed the safety and efficacy of LSD-assisted psychotherapy in patients with anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. After 12 months of LSD psychotherapy, 10 participants reported a reduction in anxiety (77.8%) and a rise in quality of life (66.7%) (Gasser et al., 2015). LSD has also been investigated as a treatment for several mental disorders, including alcoholism, opioid addiction, and anxiety and depression associated with terminal illness (Schmid et al., 2021). Ayahuasca, a natural psychedelic brew prepared from Amazonian plants and rich in DMT and harmine, induces subjective well-being and may therefore have antidepressant actions (Osório Fde et al., 2015). Palhano-Fontes et al. observed significant antidepressant effects of ayahuasca when compared to placebo in 29 patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019). MDMA is the main psychoactive substance in the party drug ecstasy, which is known to increase feelings of empathy and social engagement, heighten mood states, and facilitate the processing of difficult emotions (Holze et al., 2020). An observational study suggests that MDMA use is associated with a lower risk of depression (Jones and Nock, 2022). MDMA-assisted behavioral therapy is highly efficacious in individuals with severe PTSD including those with common comorbidities such as dissociation, depression, substance use disorders, and childhood trauma (Mitchell et al., 2021).

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we synthesized the results of all clinical trials on psychedelic-assisted therapy or monotherapy published after 1960. We examined the effect sizes of psychedelics (LSD, ayahuasca, psilocybin, and MDMA) on mood disorders (depression, anxiety, negative emotions in people with substance-use disorders [SUD] and terminal illness), and other mental disorders (such as alcohol use disorder and PTSD) at the primary endpoints. We also analyzed the emotional effects of psychedelics on healthy subjects to evaluate the safety of psychedelics. Finally, we discussed the side effects of psychedelics in the treatment of mental illness. Overall, we aimed to synthesize the best available clinical evidence on these therapies and propose directions for future research.

2. Methods

The protocol for this review was preregistered with PROSPERO (CRD42022369783). The search and selection strategy was designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

2.1. Literature search

Web of Science, Embase, EBSCO, and PubMed were systematically searched in February 2024. Search string used was ((Hallucinogens[MeSH Terms] OR (Hallucinogenic Agents) OR (Psychedelic Agents) OR (Psychotomimetic Agents) OR (Hallucinogenic Substances) OR (Hallucinogenic Drugs) OR (psychedelic) OR (ecstasy) OR (MDMA) OR (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) OR (psilocybin) OR (Lysergic Acid Diethylamide) OR (LSD) OR (ayahuasca) OR (dimethyltryptamine) OR (DMT) OR (mescaline) OR (2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine) OR (DOI)) AND (psychiatr* OR "mental*" OR neuropsych* OR "personality disorder*" OR "mood disorder*" OR "affective disorder*" OR "depressi*" OR anxi* OR post-traumatic* OR PTSD OR "bipolar disorder*" OR schizophren* OR autis* OR ADHD OR "eating disorder*" OR "substance abuse" OR "substance dependence" OR "alcohol use" OR anorexia OR bulim* OR schizoaffect* OR psychosis OR antipsychotic* OR antidepressant*)) AND ((randomized controlled trial[Publication Types]) OR (controlled clinical trial[Publication Types]) OR (randomized[Title and/or abstract]) OR (placebo[Title and/or abstract]) OR (randomly[Title and/or abstract]) OR (clinical trial[Title and/or abstract]) OR (groups[Title and/or abstract]) OR ("open label"[Title and/or abstract])). Study selection was performed by three independent researchers (Y.Y., D.G., and T.S.L.). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies included were selected according to the following criteria: 1) They were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. 2) The studies included participants with mood disorders, and patients diagnosed using the DSM-IV or DSM-V who met criteria for anxiety, mood, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), MDD, recurrent MDD, or life-threatening illness related anxiety/depression. Patients also had been diagnosed with TRD of at least moderate severity, with most meeting the criteria for severe depression (HAM-D > 24; BDI > 30). Participants with a DSM-IV diagnosis of anxiety and/or mood symptoms were included. SUD patients (who met the criteria for admission into treatment at Takiwasi (Giovannetti et al., 2020)) were evaluated using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence and had at least 4 heavy drinking days during the 30 days before screening (defined as 5 or more drinks in a day for a man and 4 or more drinks in a day for a woman). PTSD patients met DSM-5 criteria for current PTSD (CAPS-5 Total Severity Score of 35 or greater at baseline). The participants were exposed to psychedelic as an add-on treatment or monotherapy. 3) Studies assessing adverse reactions related to psychedelic use were also included. 4) Experimental studies: randomized controlled clinical trials (RCT), quasi-RCTs, and controlled clinical trials. Both single-group and between-group designs were eligible. Because of the difficulty of blinding psychedelics, a large number of clinical studies have used non-RCT research methods such as single group pre-post designs. We included these non-RCT studies to avoid missing this part of the evidence. 5) Psychological scales were measured as an outcome before and after psychedelic treatment.

Studies were excluded using the following criteria: 1) Animal studies, 2) outdated data published before 1960, 3) studies published as abstracts only, conference abstracts, case series and case reports, observational studies, and cross-sectional surveys. Other exclusions were: 4) missing data necessary for computing effect sizes, and 5) lack of baseline or relevant control groups or objective measurement scales.

Articles about the effects of different psychedelics on healthy subjects and articles that could not be used for meta-analysis because data could not be extracted or the number of studies on related diseases was too small were used as systematic reviews.

2.3. Data extraction

The primary outcome of interest was the treatment effects on mental disorders, as indicated by pre-/post-scores of symptomatology using standard measures, as well as the statistical significance of results. All effect sizes were calculated as standardized mean differences between groups on primary outcome measures, comparing the active treatment groups to the control (placebo) groups or comparing the active treatment group before and after the treatment. We extracted the following data from the study: authors, year of publication, type of study design (single group pre/post or placebo-controlled), specific disorder (depression, anxiety, or substance-use disorders, alcohol use disorder, and PTSD), psychedelic drug, primary outcome measure, sample size, drug dose, number of dosing sessions, type of control group, primary endpoint (first assessment after treatment and the end point of the follow-up period) and main findings for that endpoint and side effects. We also extracted participants’ demographics (sex, average age). We selected symptom scales based on those most frequently used to assess anxiety and depression in the literature. If an article used multiple scales to evaluate an indicator, the scale used most frequently in the literature was selected. We selected the following scales for depression: Back Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression (HADS-D), Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology Self Report (QIDS-SR-16). For Anxiety, we used: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). For Suicide, we used: Montgomery-asberg Depression Rating Scale-Suicide (MADRS-SI) and Social Introversion (SI). We used for AUD: percentage of heavy drinking days; for PTSD: Clinical-Administered Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS) in sequence. When data were not available in these articles, we contacted the corresponding authors of each included trial by email to improve data collection. When authors did not respond after contact, we performed a graphical extraction and used Plot Dligitizer to calculate the standardized mean differences. This extraction was performed by both reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

2.4. Statistical analyses

In cases where continuous outcomes were reported, Hedges’ g was used to handle the heterogeneity of different measurement or scale for same outcome and was calculated as effect size by means, standard deviations, and sample sizes using Stata MP 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). In contrast, for categorical outcomes were reported, such as studies that only give the number of people in remission before and after treatment, the odds ratio (ORs) was used for the calculations. For the RCTs studies we used the difference between the control and experimental groups for calculations, whereas for the single group pre-post studies we used the mean change from baseline. For studies where multiple measurement time points existed, we used the difference from baseline at the last time point of follow-up in order to assess the long-term (or discreet) effects of psychedelic. The effect sizes describe treatment effects on mental disorders, such that larger negative numbers indicate stronger efficacy on symptoms. We included studies that reported the outcomes by the following: (a) psychedelics dose and (b) separately for sessions before and after cross-over, with each outcome having their data combined. The pooled standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidential interval (95% CI) for continues variables and ORs and 95% CI for categorical variables were estimated in the meta-analysis. Additionally, all analyses were performed with a random-effect model, which considers both between-study and within-study variability. The heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic, and categorized as low (I2 < 25%), moderate (I2 = 25–50%), or high (I2 > 50%). Subgroup analyses were performed on different psychedelics, disorder types, duration of efficacy, and efficacy index. Meta-regression was used to explore the heterogeneity of the results, including dose, age of the subjects, female proportion, and number of study participants. Two different analyses were used to evaluate the potential impact of publication bias on the present meta-analysis—Funnel plots and Egger's regression test. The sensitivity analysis was also conducted by eliminating each study one at a time to evaluate the stability of the results.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

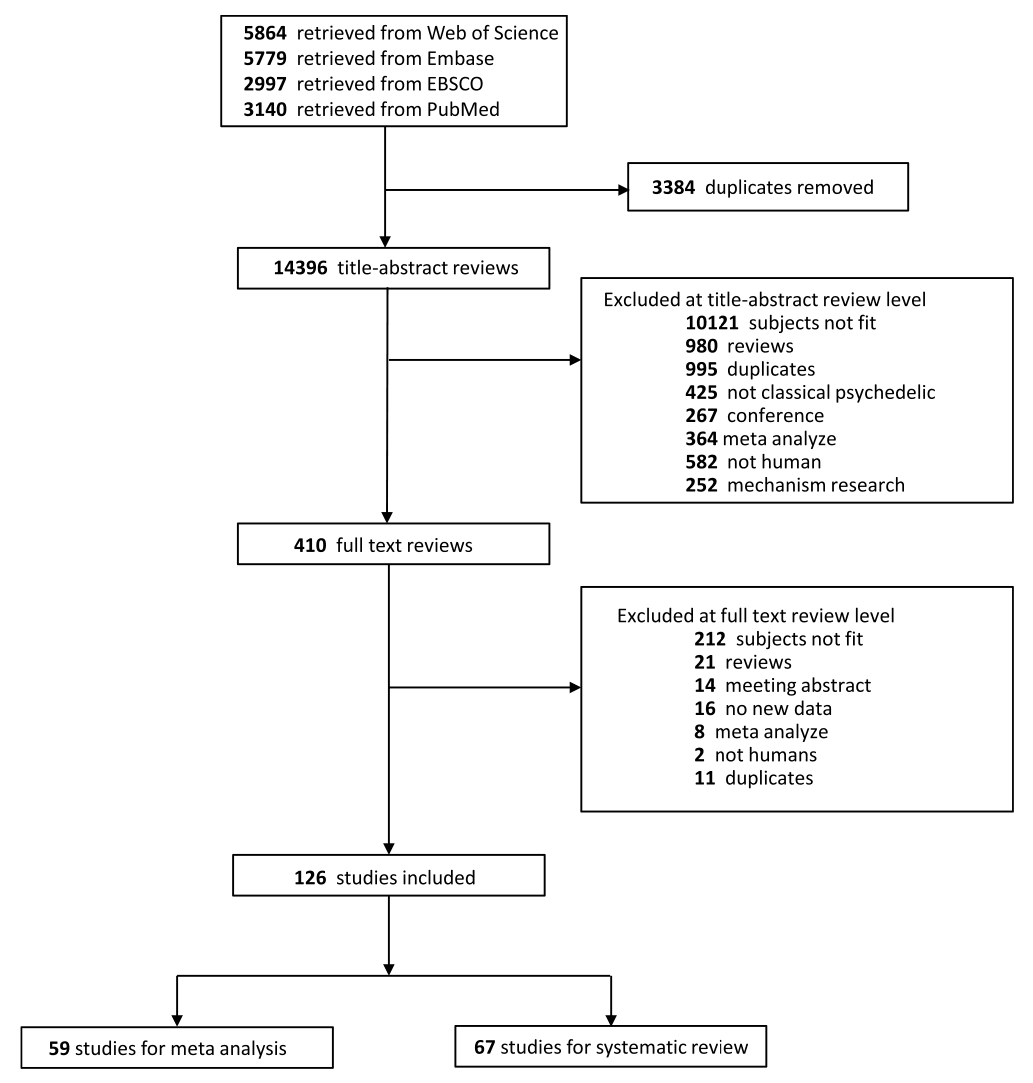

A flow diagram shows the specific steps in the article selection procedure (Fig. 1). Initially, a total of 17,780 citations from different databases were obtained. Redundance and duplicates were removed, and the remaining 14,396 titles and/or abstracts were screened. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 126 articles were finally included in the study, of which 59 were used for meta-analysis and 67 were used for systematic reviews.

3.2. Characteristics of studies

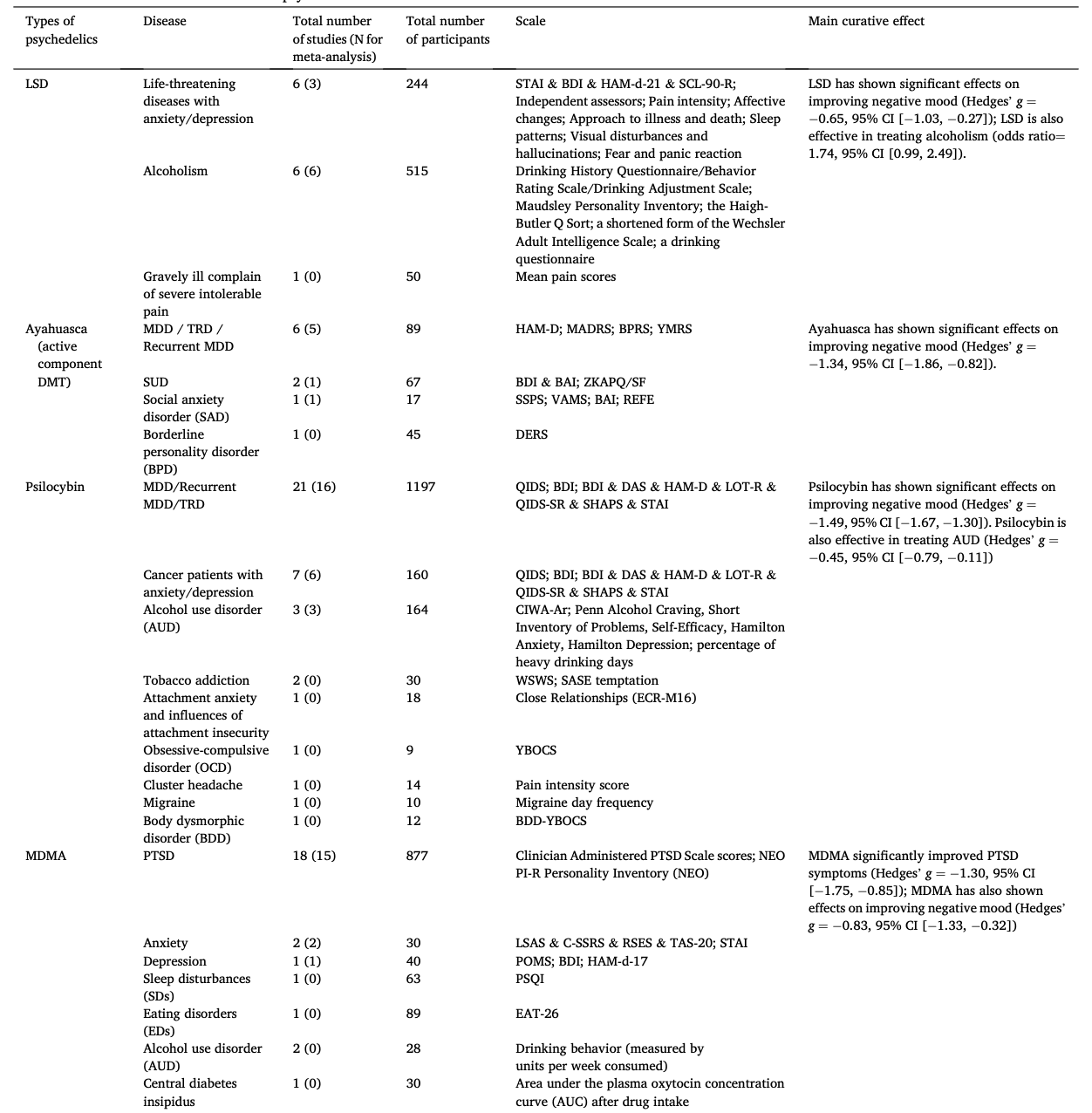

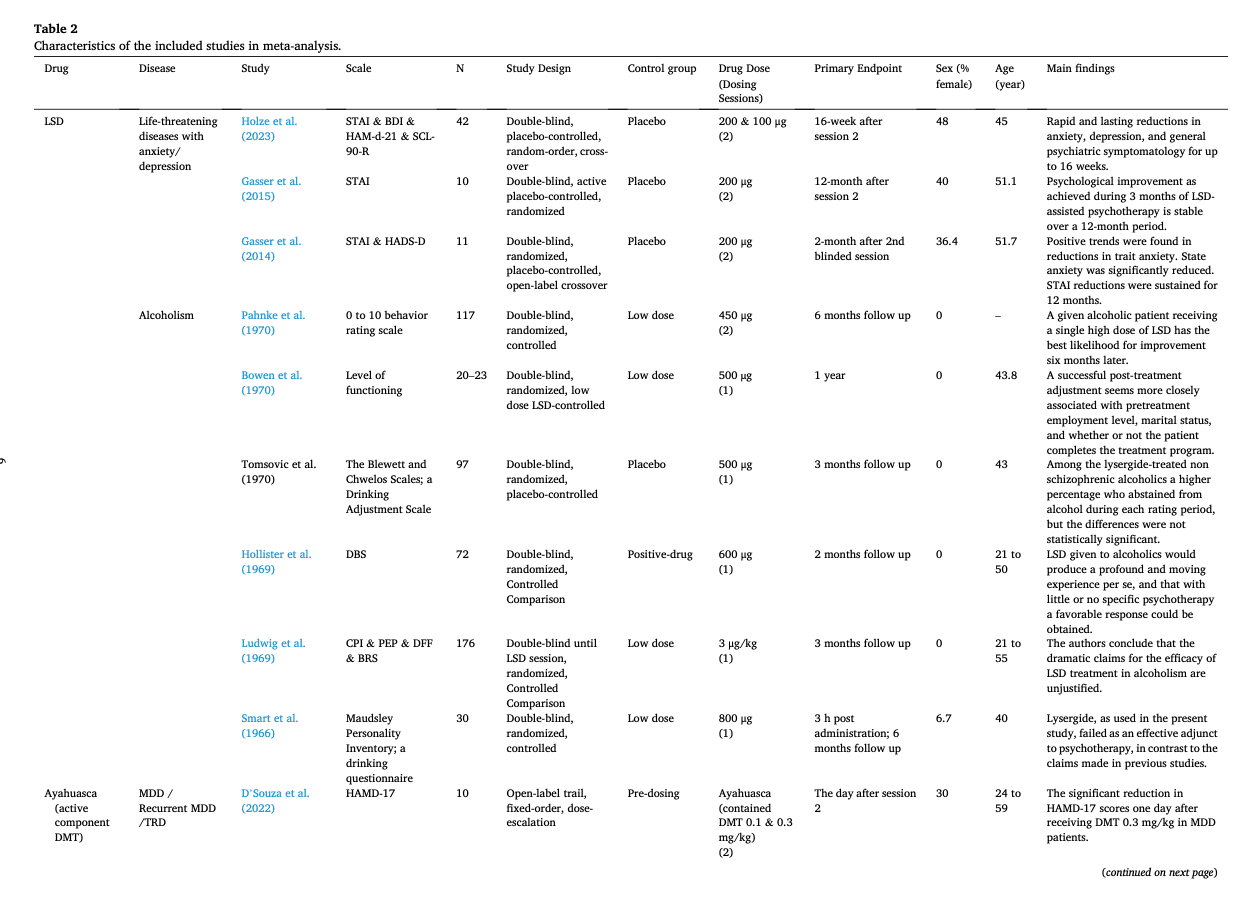

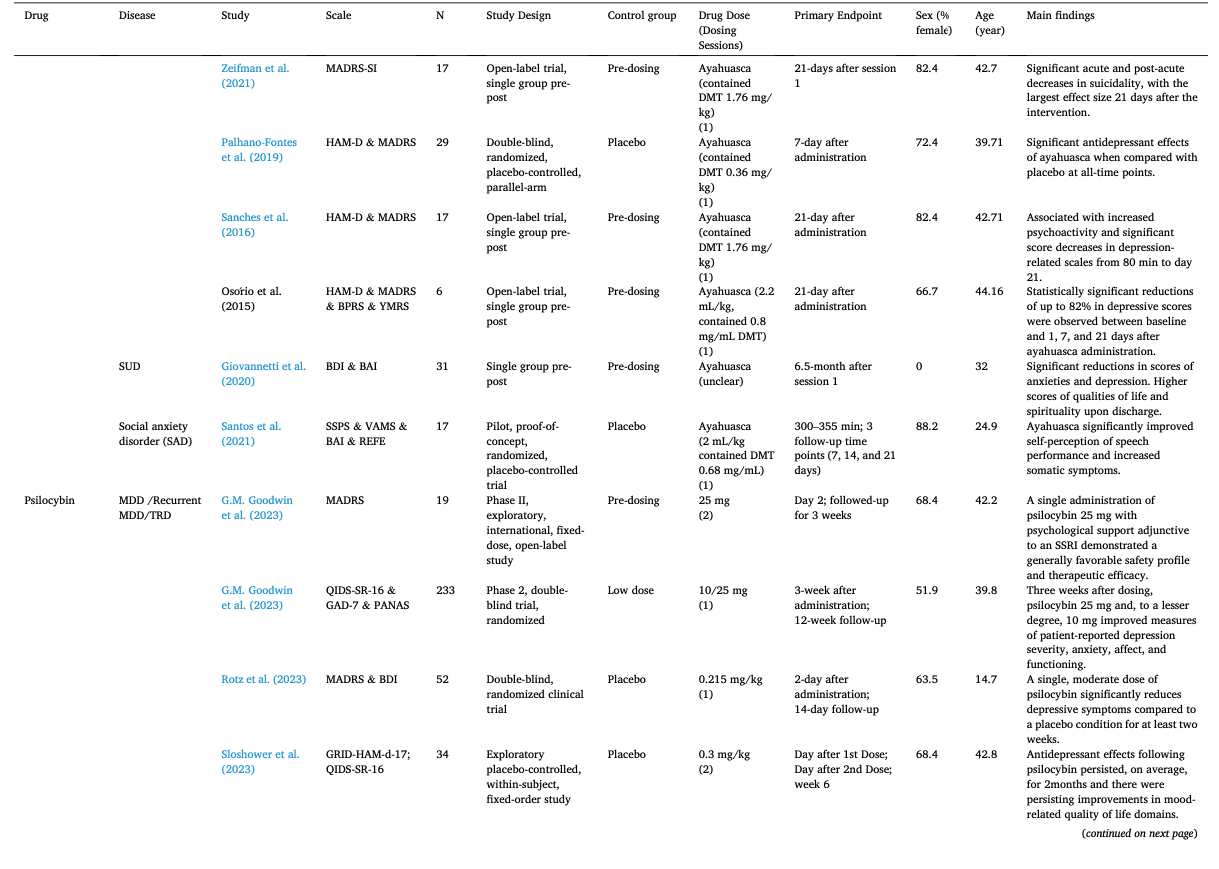

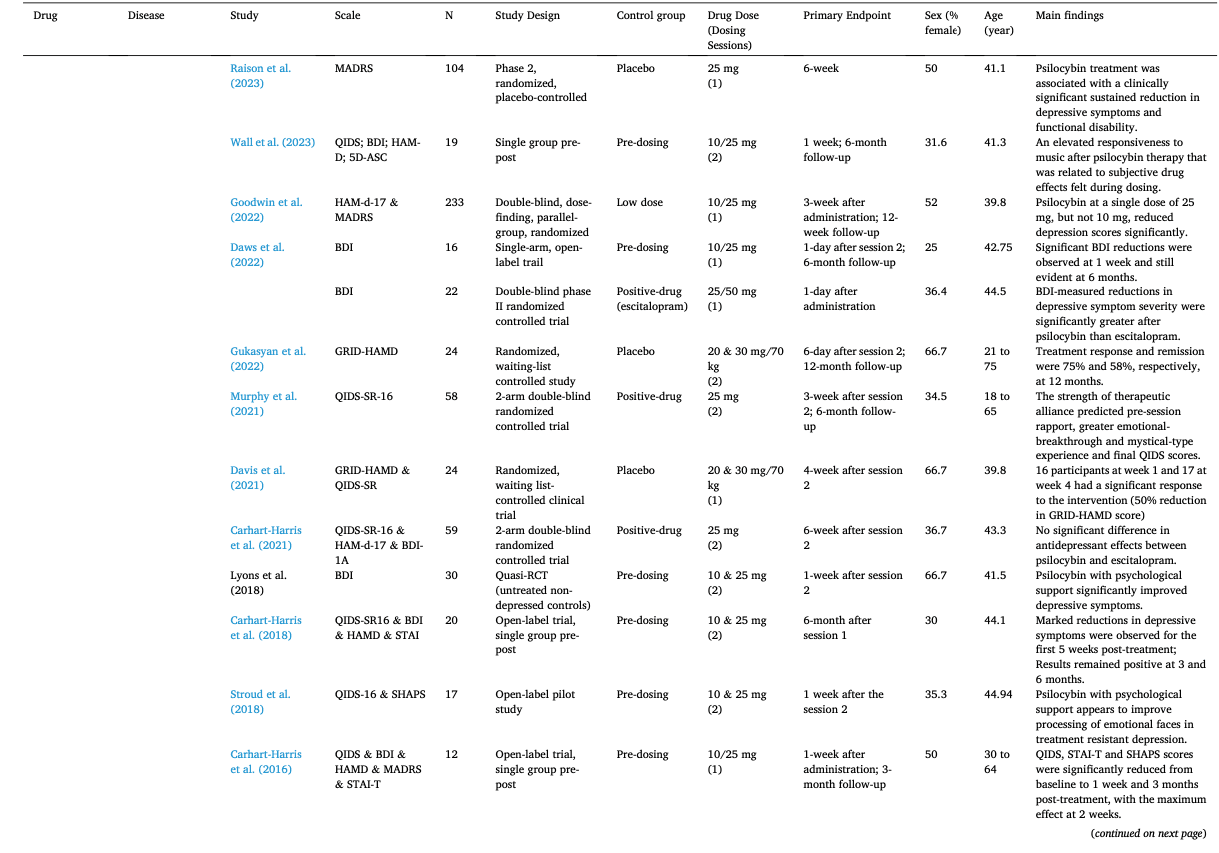

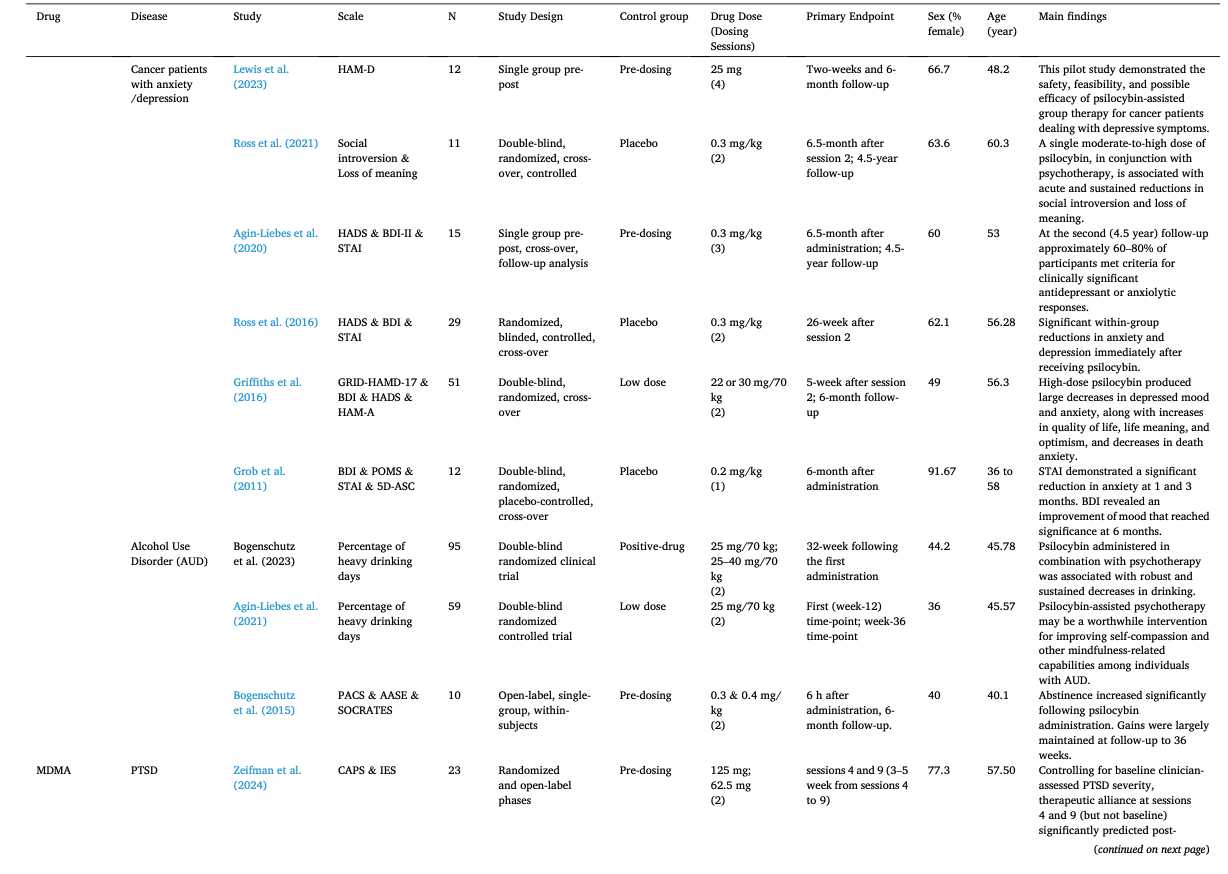

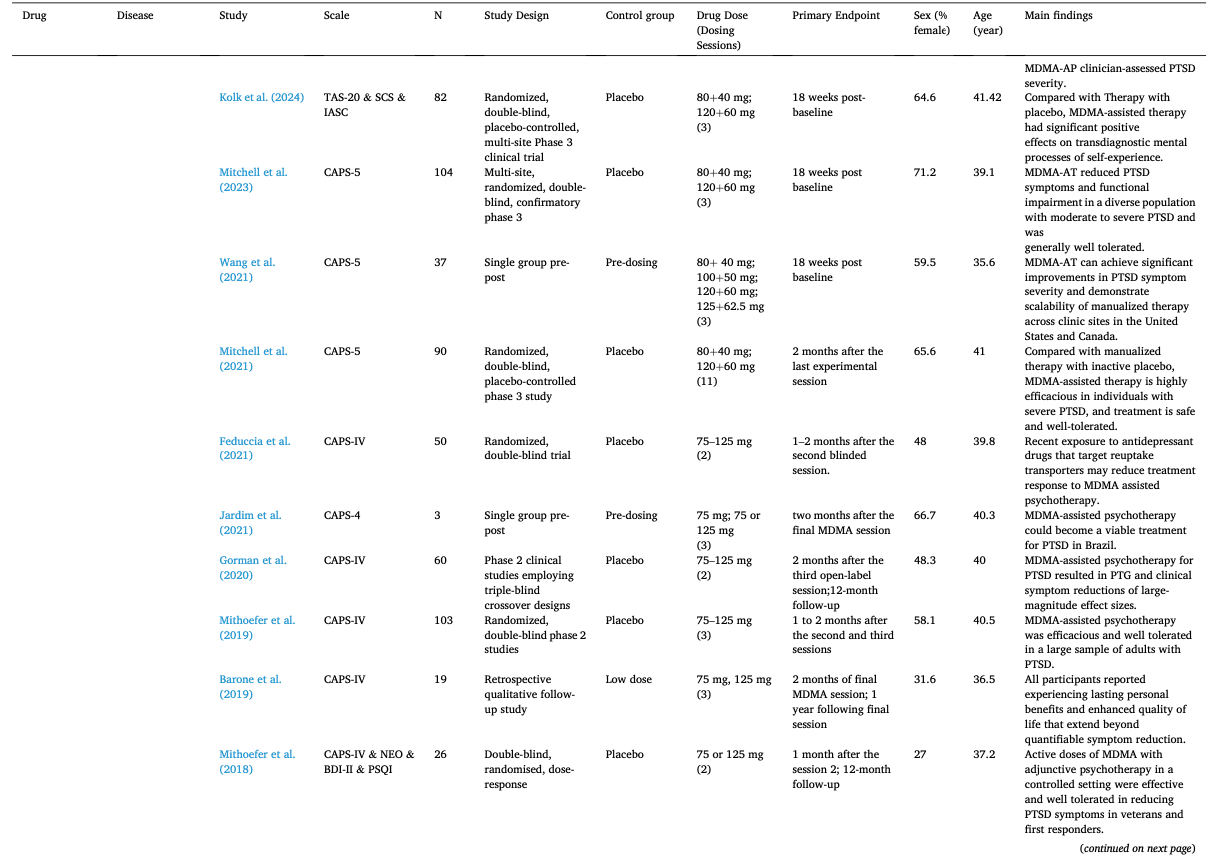

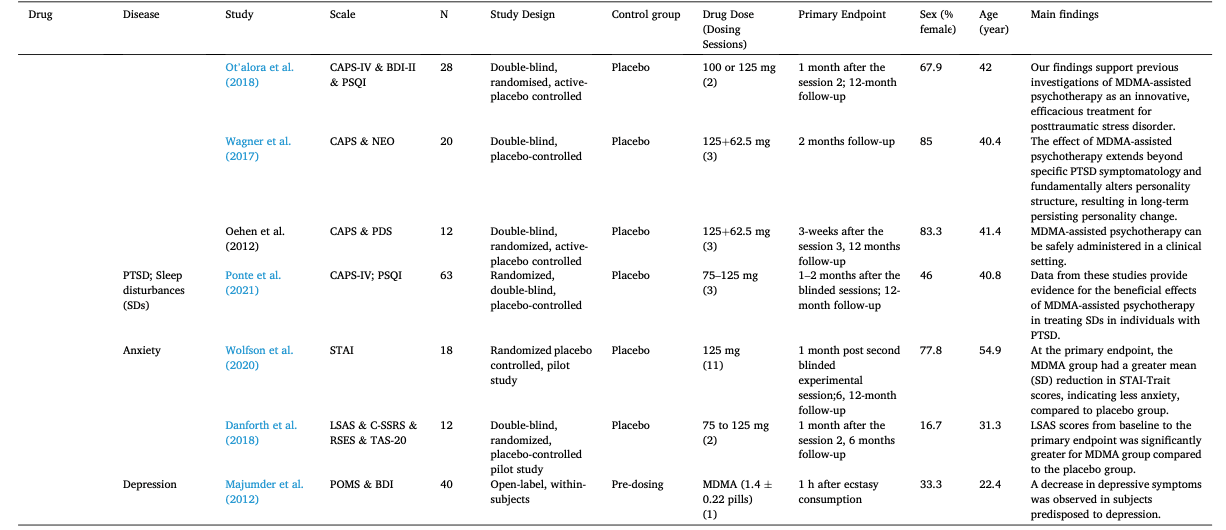

Table 1 summarizes the studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis: MDMA has the largest number of articles on treating PTSD (N = 18); Ayahuasca (N = 7) and psilocybin (N = 28) have the largest number of articles on treating mood disorders; LSD has six articles on treating mood disorders and six on alcoholism. The main characteristics of each study included in meta-analysis, as detailed in the Methods, are outlined in Table 2 (Agin-Liebes, 2021; Agin-Liebes et al., 2020; Barone et al., 2019; Bogenschutz et al., 2015, 2022; Bowen et al., 1970; Carhart-Harris et al., 2021, 2018, 2016a; D'Souza et al., 2022; Danforth et al., 2018; Davis et al., 2021; Daws et al., 2022; Dos Santos et al., 2021; Feduccia et al., 2021; Gasser et al., 2014, ; 2015; Giovannetti et al., 2020; Goodwin et al., 2022; G.M. Goodwin et al., 2023a, 2023b; Gorman et al., 2020; Griffiths et al., 2016; Grob et al., 2011; Gukasyan et al., 2022; Hollister et al., 1969; Holze et al., 2023; Jardim et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2023; Ludwig et al., 1969; Lyons and Carhart-Harris, 2018; Majumder et al., 2012; Mitchell et al., 2021, 2023; Mithoefer et al., 2019, 2018; Murphy et al., 2021; Oehen et al., 2013; Osório Fde et al., 2015; Ot'alora et al., 2018; Pahnke et al., 1970; Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019; Ponte et al., 2021; Raison et al., 2023; Ross et al., 2021, 2016; Sanches et al., 2016; Sloshower et al., 2023; Smart et al., 1966; Stroud et al., 2018; Tomsovic and Edwards, 1970; van der Kolk et al., 2024; von Rotz et al., 2023; Wagner et al., 2017; Wall et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021; Wolfson et al., 2020; Zeifman et al., 2024, 2021). Supplementary Table 1 (Apud et al., 2023; Atila et al., 2023; Barba et al., 2022; Brewerton et al., 2022; Christie et al., 2022; D'Souza et al., 2022; Dominguez-Clave et al., 2019; Doss et al., 2021; Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al., 2005; Grof et al., 1973; Johnson et al., 2014; Kast, 1967; Kast and Collins, 1964; Moreno et al., 2006; Nicholas et al., 2022; Pahnke et al., 1969; Roseman et al., 2018; Schindler et al., 2021, 2022; Schneier et al., 2023; Sessa et al., 2021, 2019; Shnayder et al., 2023; Singleton et al., 2023; Stauffer et al., 2021; Timmermann et al., 2024; Vogt et al., 2023; Weiss et al., 2023; Zeifman et al., 2023) summarized the main characteristics of each of the studies included in the systematic review that could not be used in the meta-analysis because of the unavailability of primary data or the number of studies on related diseases was too small. This part covered psychedelics for the treatment of specific symptoms and other mental disorders, which will be discussed in detail in Part III. Supplementary Table 2 (Baggott et al., 2016; Barrett et al., 2020; Becker et al., 2022; Bedi et al., 2010; Bershad et al., 2019; Bosker et al., 2010; Carbonaro et al., 2018; de Wit et al., 2022; Dolder et al., 2018, 2016; Doss et al., 2018; Dudysová et al., 2020; Griffiths et al., 2011; Grob et al., 1996; Hutten et al., 2020; Hysek et al., 2013, 2014; Kiraga et al., 2022; Kometer et al., 2012; Kraehenmann et al., 2015; Kuypers et al., 2008, 2018; Liechti et al., 2000a, 2000b; Marschall et al., 2022; Perkins et al., 2022; Perna et al., 2014; Pokorny et al., 2017; Ramaekers et al., 2021; Rucker et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2007; Schmid et al., 2014; Schmid and Liechti, 2018; Uthaug et al., 2021; van Wel et al., 2012; Wardle and de Wit, 2014) provided a summary of the main features of studies on the effects of different psychedelics on healthy subjects as another part of the systematic review, which involved 40 studies.

Most studies used only a single or two doses and the largest number focused on psilocybin (43.6%) with 29.9% involving MDMA, 14.9% involving LSD, and 11.5% involving ayahuasca. These psychedelics were used in five major groups of people: depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, PTSD, substance-use disorders related anxiety/depression, and life-threatening illness related anxiety/depression. The latter two groups were usually associated with adverse psychological states. Two subtypes of depressive disorder were classified as MDD and recurrent MDD/TRD, respectively.

The average post-treatment evaluation time was 11.97 weeks (SD = 11.88, range = 0 to 52). For studies with a follow-up assessment (51.7%), the last follow-up occurred 9.65 months on average (SD = 12.50, range = 0.5 to 54) after treatment. Except for some articles (Bogenschutz et al., 2022; Goodwin et al., 2022; G.M. Goodwin et al., 2023a, 2023b; Hollister et al., 1969; Ludwig et al., 1969; Mitchell et al., 2021, 2023; Mithoefer et al., 2019; Pahnke et al., 1970; Raison et al., 2023; Tomsovic and Edwards, 1970), most of them used small sample sizes with an average of 23.46 participants (SD = 13.30, range = 3 to 52). The mean age was 43.74 years old and 53.94% of the samples were female. A more detailed description will be displayed in the subgroup analysis.

3.3. Part I: psychedelics for the treatment of mood disorders

3.3.1. Overall effect sizes

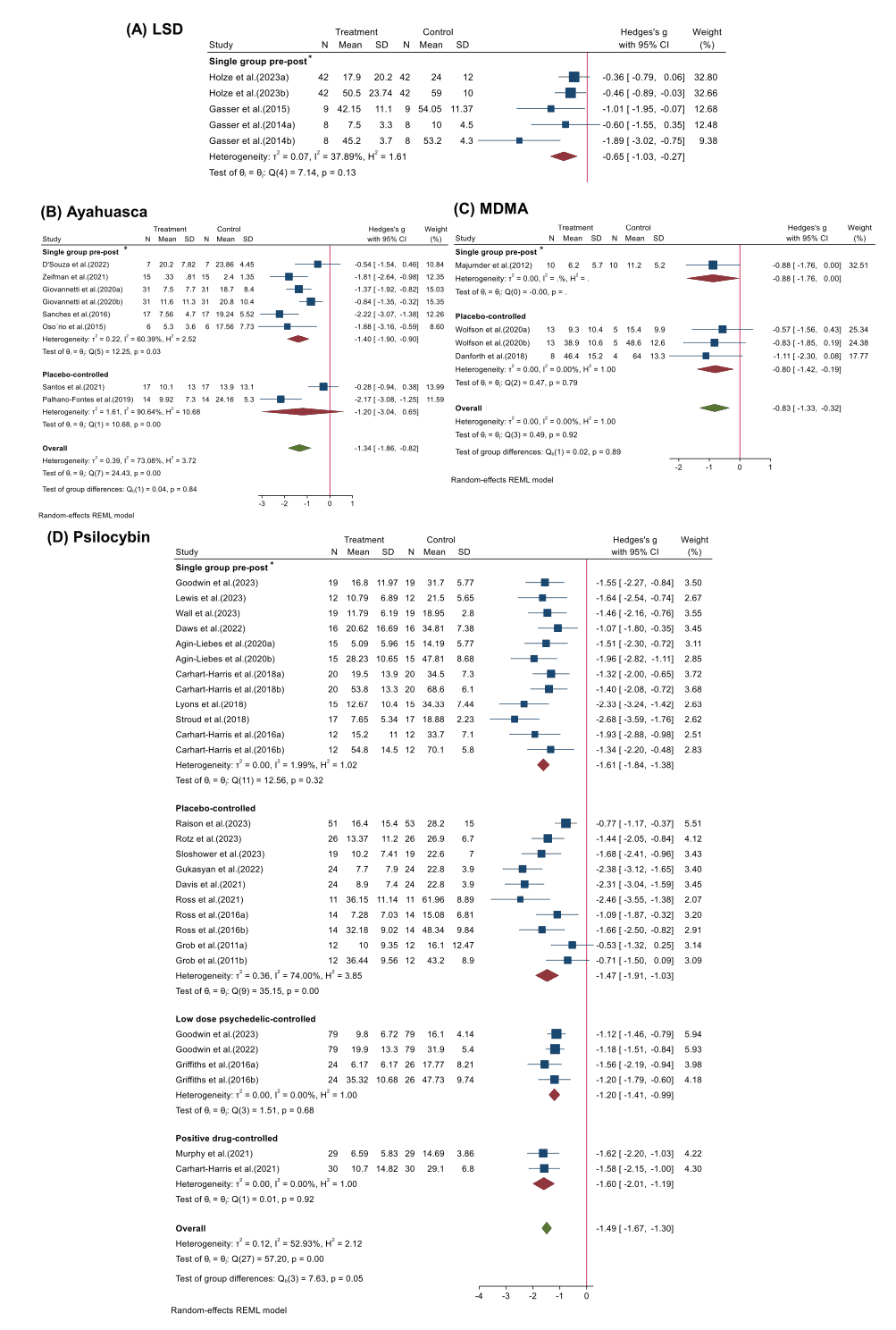

We conducted analyses of therapeutic effects across these 35 studies for four psychedelics: LSD, ayahuasca, psilocybin, and MDMA (Fig. 2). Overall, different psychedelics have improved negative mood to some extent. Specifically, psilocybin (Hedges’ g = −1.49, 95% CI [−1.67, −1.30], I2 = 52.93%, p < 0.001) in 22 studies showed the strongest therapeutic effect among four psychedelics, followed by ayahuasca (Hedges’ g= −1.34, 95% CI [−1.86, −0.82], I2 = 73.08%, p < 0.001) in 7 studies and MDMA (Hedges’ g= −0.83, 95% CI [−1.33, −0.32], I2 = 00.00%, p = 0.92) in 3 studies, while the effect of LSD (Hedges’ g = −0.65, 95% CI [−1.03, −0.27], I2=37.89%, p = 0.13) in another 3 studies was lower possibly due to the small number of included studies. Due to a relatively comprehensive study collection, this meta-analysis included clinical studies from a wide range of study types after excluding case series and case reports, observational studies, and cross-sectional surveys. Therefore, we conducted a subgroup analysis to discuss the effects of study designs of different psychedelics for the treatment of mood disorder. Specifically, four types were categorized: 1″Single group pre-post", 2″Placebo-controlled", 3″Low dose psychedelic-controlled", 4″Positive drug-controlled". It was found that the clinical studies of LSD contained only single group pre-post study designs (Hedges’ g = −0.65, 95% CI [−1.03, −0.27], I2 = 37.89%, p = 0.13) (Fig. 2A). Single group pre-post studies (Hedges’ g = −1.40, 95% CI [−1.90, −0.90], I2 = 60.39%, p = 0.03) on ayahuasca reported stronger efficacy than placebo-controlled (Hedges’ g = −1.20, 95% CI [−3.04, 0.65], I2 = 90.64%, p = 0.00) (Fig. 2B). A similar condition was seen in the MDMA studies which showed that single group pre-post studies (Hedges’ g = −0.88, 95% CI [−1.76, 0.00]) was slightly higher than placebo-controlled (Hedges’ g = −0.80, 95% CI [−1.42, −0.19], I2 = 00.64%, p = 0.79) (Fig. 2C). Psilocybin had the richest study design encompassing four of types mentioned above (Fig. 2D). Single group pre-post studies (Hedges’ g = −1.61, 95% CI [−1.84, −1.38], I2 = 1.99%, p = 0.32) seemed to overestimate efficacy, and the greater heterogeneity of groups using placebo controls (Hedges’ g = −1.47, 95% CI [−1.91, −1.03], I2 = 74.00%, p = 0.00) was reported. Heterogeneity was lower using low dose (Hedges’ g = −1.20, 95% CI [−1.41, −0.99], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.68) and positive drug controls (Hedges’ g = −1.60, 95% CI [−2.01, −1.19], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.92) and it appears that psilocybin showed superior efficacy to citalopram.

3.3.2. Subgroup analyses

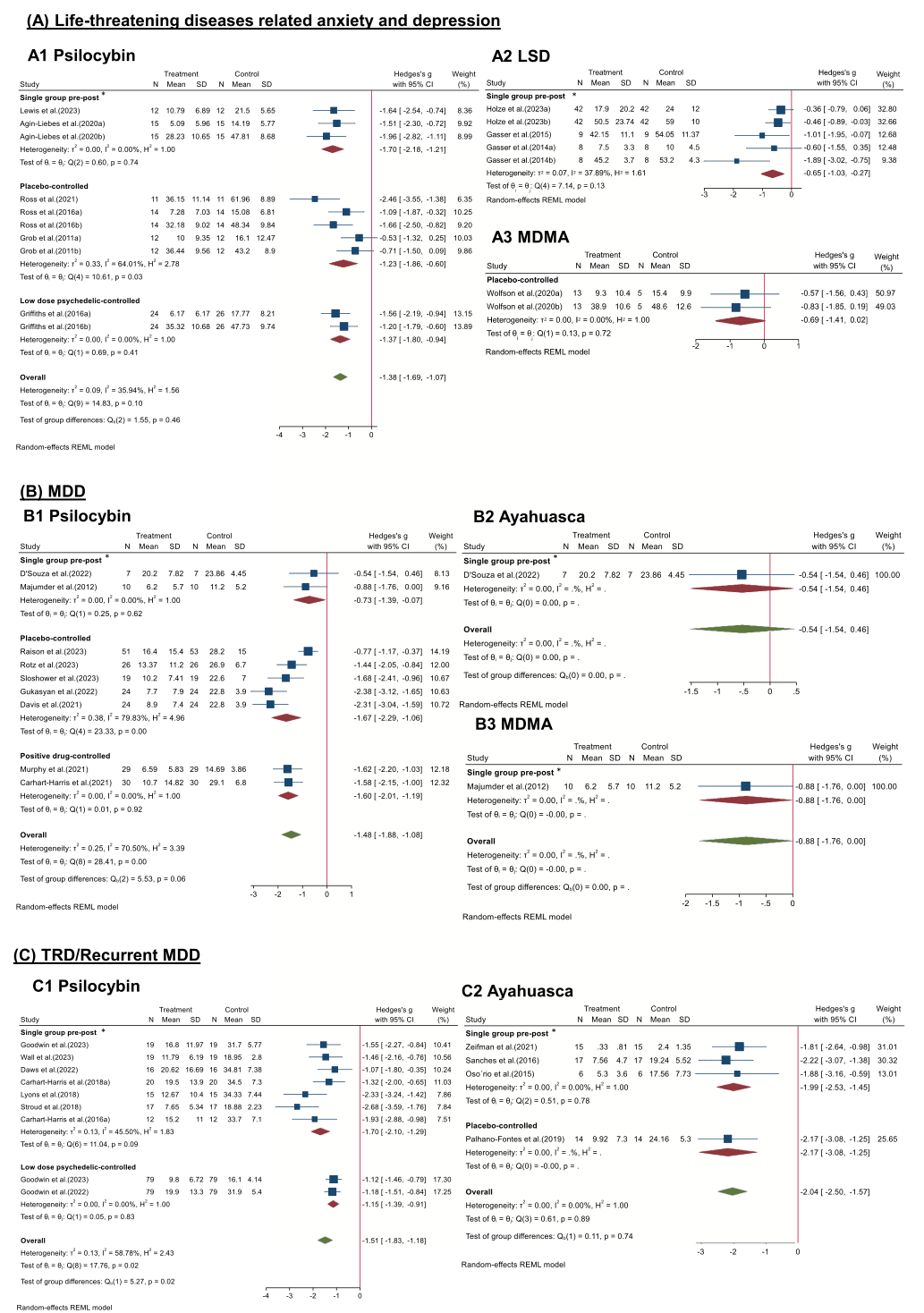

Disorder type: Previous clinical trials suggested that psychedelics were effective not only for depression (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Gukasyan et al., 2022; Majumder et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2021; Raison et al., 2023; Sloshower et al., 2023; von Rotz et al., 2023), but also for TRD and recurrent depression (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018, 2016a; Daws et al., 2022; Goodwin et al., 2022; G.M. Goodwin et al., 2023a; Lyons and Carhart-Harris, 2018; Osório Fde et al., 2015; Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019; Sanches et al., 2016; Stroud et al., 2018; Wall et al., 2023; Zeifman et al., 2021), in patients for whom general antidepressants are not effective enough. In addition, they had shown promising preliminary results for treating negative emotions in people with SUD (Giovannetti et al., 2020) and terminal illness (Agin-Liebes et al., 2020; D'Souza et al., 2022; Gasser et al., 2014, 2015; Griffiths et al., 2016; Grob et al., 2011; Holze et al., 2023; Lewis et al., 2023; Ross et al., 2021, 2016; Wolfson et al., 2020), as well as in populations with social anxiety disorders (Dos Santos et al., 2021) (Fig. 3). For the population with life-threatening diseases related anxiety and depression (Fig. 3A), psilocybin showed stronger efficacy (Hedges’ g = −1.38, 95% CI [−1.69, −1.07], I2 = 35.94%, p = 0.10) than LSD and MDMA in all types of study designs. Specifically, across three studies types, effect sizes of single group pre-post (Hedges’ g = −1.70, 95% CI [−2.18, −1.21], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.74), placebo-controlled (Hedges’ g = −1.23, 95% CI [−1.86, −0.60], I2 = 64.01%, p = 0.03), low dose psychedelic-controlled (Hedges’ g = −1.37, 95% CI [−1.80, −0.94], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.41) indicated different reductions of anxiety and depression. Besides, LSD (Hedges’ g = −0.65, 95% CI [−1.03, −0.27], I2 = 37.89%, p = 0.13) and MDMA (Hedges’ g = −0.69, 95% CI [−1.41, −0.02], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.72) also indicated slight reductions of anxiety and depression. For the MDD population (Fig. 3B), psilocybin has been most widely reported in the research articles. Across three studies types, effect sizes of single group pre-post (Hedges’ g = −0.73, 95% CI [−1.39, −0.07], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.62), placebo-controlled (Hedges’ g = −1.67, 95% CI [−2.29, −1.06], I2 = 79.83%, p = 0.00), positive drug-controlled (Hedges’ g = −1.60, 95% CI [−2.01, −1.19], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.92) indicated different reductions of MDD symptom. There was one article reported ayahuasca (Hedges’ g = −0.54, 95% CI [−1.54, −0.46]) and one reported MDMA (Hedges’ g = −0.88, 95% CI [−1.76, −0.00]) for treating MDD. For the TRD or recurrent MDD population (Fig. 3C), ayahuasca showed stronger efficacy (Hedges’ g = −2.04, 95% CI [−2.50, −1.57], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.89) than psilocybin (Hedges’ g = −1.51, 95% CI [−1.83, −1.18], I2 = 58.78%, p = 0.02), but there are more articles reported psilocybin than ayahuasca.

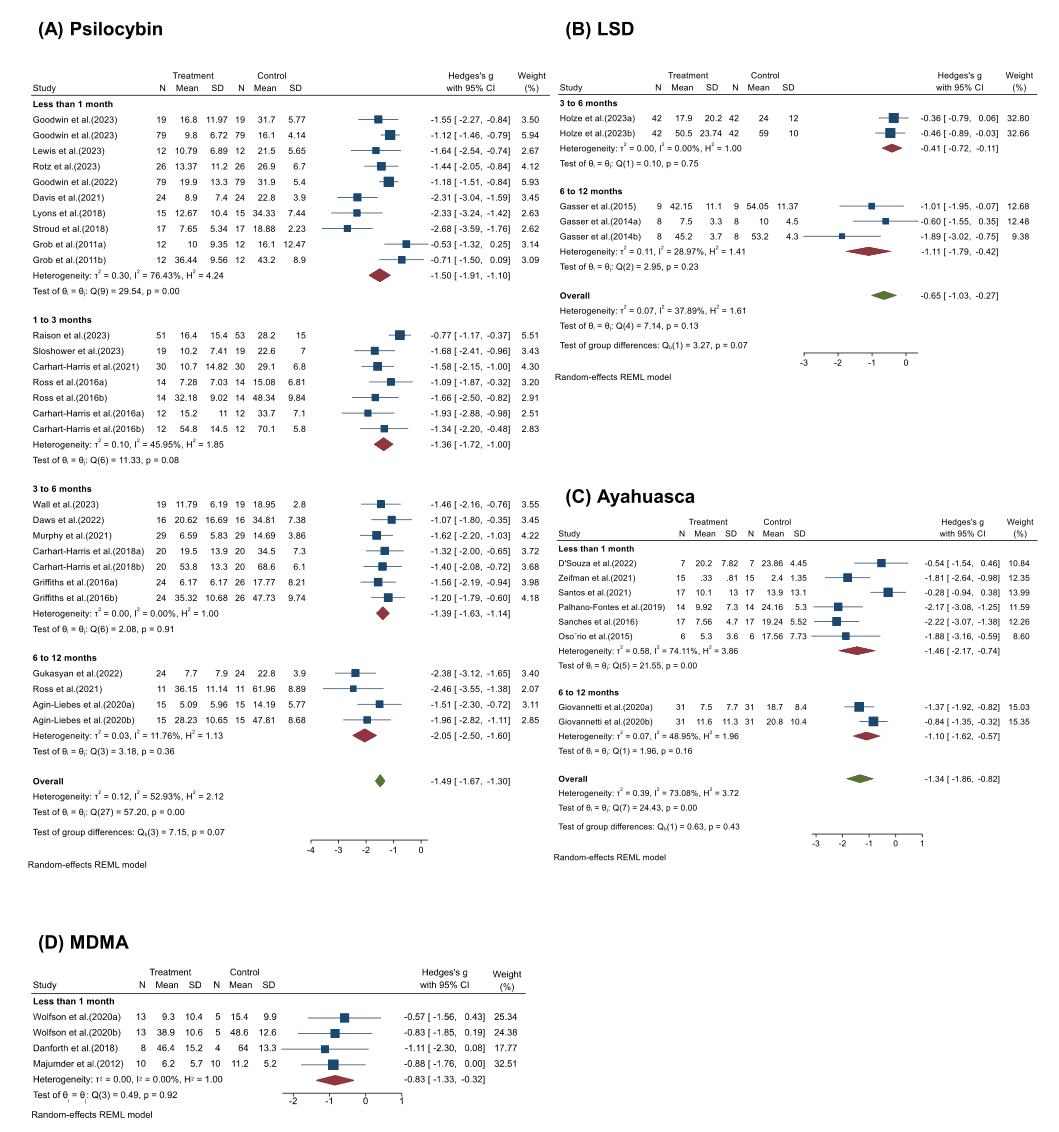

Duration of efficacy: When we compared the effects of psychedelics at different time points after the initial dose, the effects could persist for as long as one year, although the intensity of the effects may decrease over time (Fig. 4). Within a month of treatment, psychedelics showed promising efficacy, with a faster onset of action compared to traditional antidepressants. Specifically, psilocybin (Hedges’ g = −1.50, 95% CI [−1.91, −1.10], I2 = 76.43%, p < 0.001) showed similar efficacy to ayahuasca (Hedges’ g= −1.46, 95% CI [−2.17, −0.74], I2 = 74.11%, p < 0.001) at one month, while MDMA (Hedges’ g = −0.83, 95% CI [−1.33, −0.32], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.92) was slightly weaker. There was only a slight decrease of 9.3% in efficacy at 1 to 3 months after psilocybin administration (Hedges’ g = −1.36, 95% CI [−1.72, −1.00], I2=45.95%, p = 0.08). Thereafter, the efficacy of the psilocybin treatment is almost the same after 3 to 6 months (Hedges’ g = −1.39, 95% CI [−1.63, −1.14], I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.91). Nevertheless, the sustainable efficacy of psychedelics persisting six months to a year after administration seems remarkable, for psilocybin (Hedges’ g = −2.05, 95% CI [−2.50, −1.60], I2 = 11.76%, p = 0.36) and LSD (Hedges’ g = −1.11, 95% CI [−1.79, −0.42], I2 = 28.97%, p = 0.23) and ayahuasca (Hedges’ g= −1.10, 95% CI [−1.62, −0.57], I2 = 48.95%, p = 0.16), which may also be due to supplemental dosing.

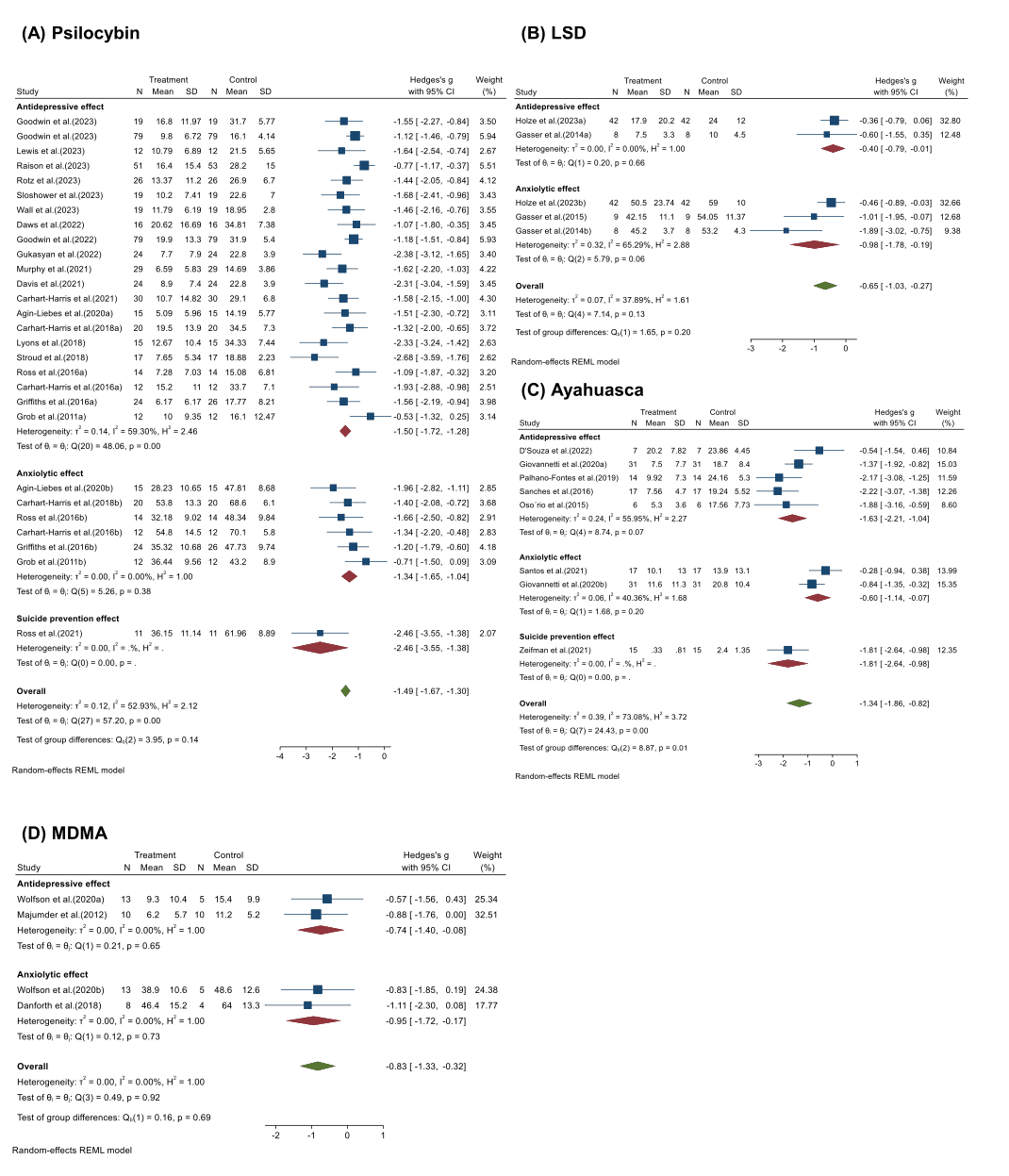

Negative mood state: When we divided the assessments of psychedelics’ therapeutic effects into three indexes based on the different scales used in previous studies (Fig. 5), psychedelics showed both anxiolytic and antidepressant effects and reduced the risk of suicide. Two reports showed consistent and robust suicide-prevention effects for psilocybin (Hedges’ g = −2.46, 95% CI [−3.55, −1.38]) and ayahuasca (Hedges’ g = −1.81, 95% CI [−2.64, −0.98). Slightly stronger antidepressant effects (Hedges’ g = −1.50, 95% CI [−1.72, −1.28], I2 = 59.30%, p < 0.001) than anxiolytic effects (Hedges’ g = −1.34, 95% CI [−1.65, −1.04], I2=0.00%, p = 0.38) was found in the treatment of psilocybin. Other classes of psychedelics also appear to vary in their anxiolytic and antidepressant effects, which may be due to differences in mechanisms of action.

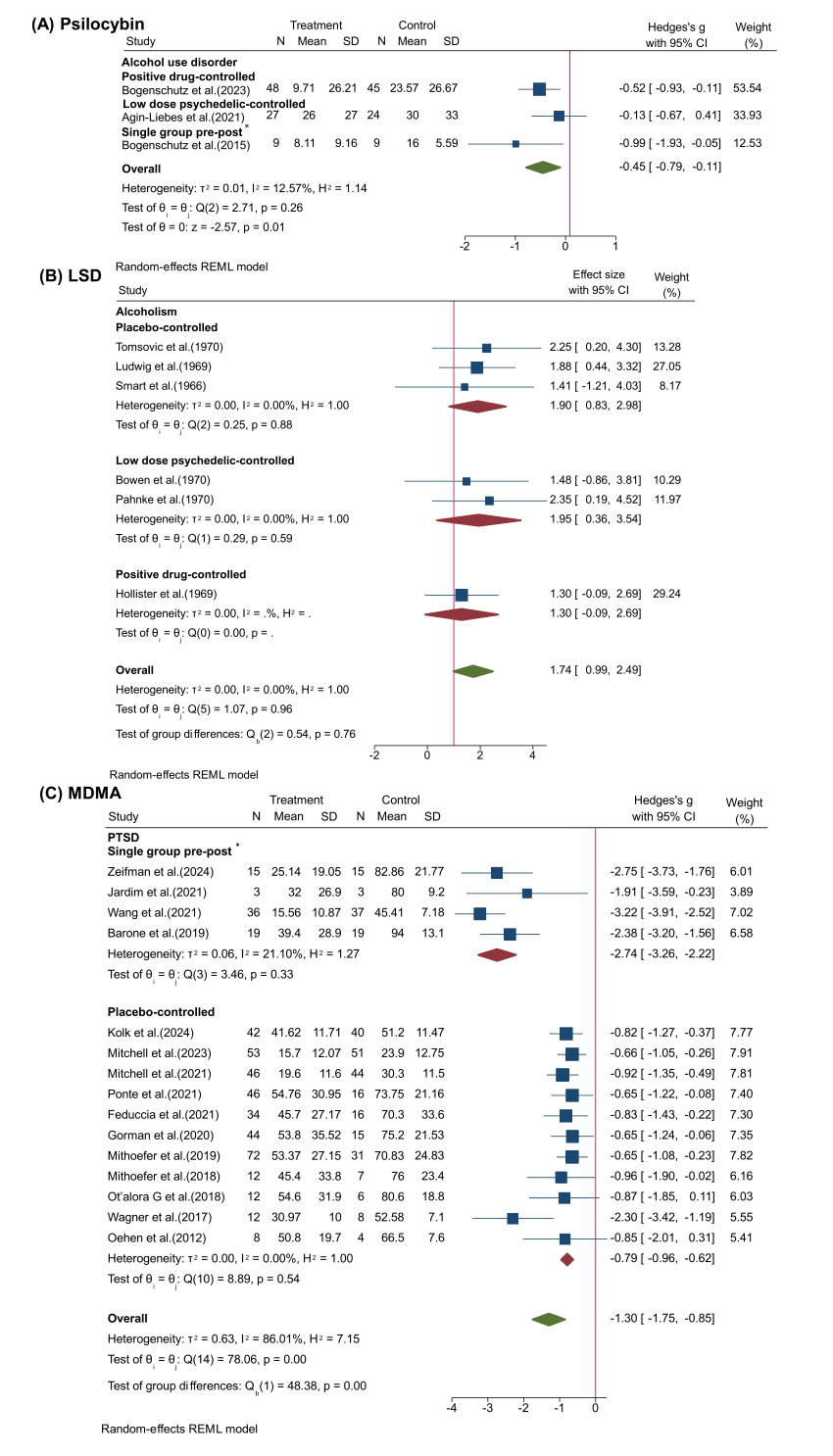

3.4. Part II: psychedelics for the treatment of substance use disorder and PTSD

Both psilocybin and LSD can help patients with SUD to better quit drinking, with three studies showing significant reductions in alcohol abuse and consumption in people treated with psilocybin in combination with psychotherapy (Hedges’ g = −0.45, 95% CI [−0.79, −0.11], I2=12.57%, p = 0.26) (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, six randomized controlled trials on LSD conducted during the 1960s for treating alcoholism reported a pooled odds ratio for improvement with LSD of 1.74 (95% CI [0.99, 2.49], I2=0.00%, p = 0.96) (Fig. 6B). These studies included three types: Placebo-controlled, low dose psychedelic-controlled and positive drug-controlled, with odds ratio of 1.90 (95% CI [0.83, 2.98], I2=0.00%, p = 0.88), 1.95 (95% CI [0.36, 3.54], I2=0.00%, p = 0.59) and 1.30 (95% CI [−0.09, 2.69), respectively. There was no significant heterogeneity within any of the groups, and it appears that positive drug-controlled showed the most conservative efficacy, however, there is no significant difference (p = 0.76).

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD has recently progressed to phase Ⅲ clinical trials and received breakthrough therapy designation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Mitchell et al., 2021). Twelve studies from 2012 to 2021 collectively found significant efficacy of MDMA in helping to reduce PTSD symptoms (Hedges’ g = −1.30, 95% CI [−1.75, −0.85], I2=86.01%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6C). Four of these single-group pre-post studies reported stronger efficacy of MDMA in the treatment of PTSD (Hedges’ g = −2.74, 95% CI [−3.26, −2.22], I2=21.10%, p = 0.33) than placebo-controlled RCTs (Hedges’ g = −0.79, 95% CI [−0.96, −0.62], I2=0.00%, p = 0.54).

3.5. Risk of publication bias

The funnel plot indicated low levels of heterogeneity and a lack of publication bias except for a few outliers (Supplementary Figure 1). A small number of studies have asymmetries, which may suggest that some studies have selected populations that are particularly sensitive to psychedelics, thus exaggerating the experimental effect size. The need for cautious, larger placebo-controlled randomized trials is highlighted by the high rate of publication bias in several domains and by the heterogeneity across studies.

3.6. Sensitivity analyses

Once more than three studies were included, leave-one-out sensitivity tests were conducted for each subgroup to make sure that the overall results were not impacted by a single study. These analyses consisted of repeating the analyses while sequentially excluding each study. Analysis showed that the combined effects of psychedelics on depression, anxiety, suicide intention, alcohol use disorder, and PTSD did not change significantly with several studies specifically omitted, indicating that the overall results obtained in this meta-analysis are robust (Supplementary Figures 2).

3.7. Moderator analyses

Since the meta-analysis covered more than 10 studies, we attempted to explore the sources of heterogeneity using meta-regression. Meta-regressions on dose (p = 0.733), number of study participants (p = 0.306), the age of the subjects (p = 0.209), and gender differences (p = 0.507) did not yield significant results as factors accounting for heterogeneity across studies (Supplementary Figures 3–6).

3.8. Part III: psychedelics for the treatment of specific symptoms and other mental disorders

Many studies have reported that MDMA has a significant therapeutic effect on PTSD. Specific symptoms contributing to this efficacy may include eating disorder symptoms, which have shown a significant reduction in total EAT-26 (Eating Attitudes Test 26) scores following MDMA-assisted therapy among participants with severe PTSD (Brewerton et al., 2022). Furthermore, sleep disturbances are among the most distressing and commonly reported symptoms of PTSD, and Ponte et al. have shown that MDMA can significantly improve sleep quality (Ponte et al., 2021). Finally, Atila et al. found that in central diabetes insipidus patients, oxytocin concentration slightly increased in response to MDMA (Atila et al., 2023).

Psilocybin-assisted therapy has shown marked success in treating depression, and some contributions may reflect reduced obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Moreno et al. observed marked decreases in obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms in all subjects during their testing sessions (23%−100% decrease in YBOCS score) and improvement generally lasted past the 24-hour time point (Moreno et al., 2006). Furthermore, a pilot study of single-dose psilocybin for body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) showed a significant decrease on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale Modified for BDD (BDD-YBOCS) score, with conviction of belief, negative affect, and disability improved after treatment(Schneier et al., 2023). Psilocybin can also reduce both cluster headaches and migraine burden (Schindler et al., 2021, 2022).

Dominguez-Clave et al. suggested a potential therapeutic effect of ayahuasca on emotion regulation and mindfulness capacities (including decentering, acceptance, awareness, and sensitivity to meditation practice) among borderline personality disorder traits (Dominguez-Clave et al., 2019). Kast et al. found LSD had profound analgesic action in severe intolerable pain although the onset of therapeutic action of LSD was somewhat slower than for opioids (Kast and Collins, 1964).

3.9. Adverse effects

Table 3 summarizes adverse reactions reported in 44 out of 70 total articles. The adverse reactions were reported in 8 LSD articles, 5 ayahuasca articles, 17 psilocybin articles, and 14 MDMA articles. Lasting negative or adverse effects resulted from the psychedelic-assisted therapy in about two-thirds of reports (62.9%). The pooled adverse events rate was 58.1% (SD = 24.1), and 19.32 (SD = 10.35) were complaints occurring during the treatment session. These adverse events included headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, insomnia, nystagmus, euphoria, muscle tension, transient increase in blood pressure, transient anxiety, and delusions, with headache being the most common. Some reports of adverse reactions to a particular psychedelic at the same dose appear to be extremely contradictory, implying that a more rigorous and standardized approach is required.

4. Discussion

We focused on the efficacy and adverse effects of four psychedelics: LSD, ayahuasca (active component DMT), psilocybin, and MDMA. The efficacy may be different due to various conditions being explored with different psychedelics. We found the efficacy of psychedelic-assisted therapy for seven different kinds of disorders: MDD, TRD/recurrent MDD, social anxiety disorder, SUD-related anxiety/depression, life-threatening illness-related anxiety/depression, alcohol use disorder, and PTSD. No serious adverse effects were reported with headache as the most common. This meta-analysis and systematic review provide evidence that psychedelic-assisted treatment is effective, with limited side effects and rapid effects along with the long-term effectiveness of one-dose treatment.

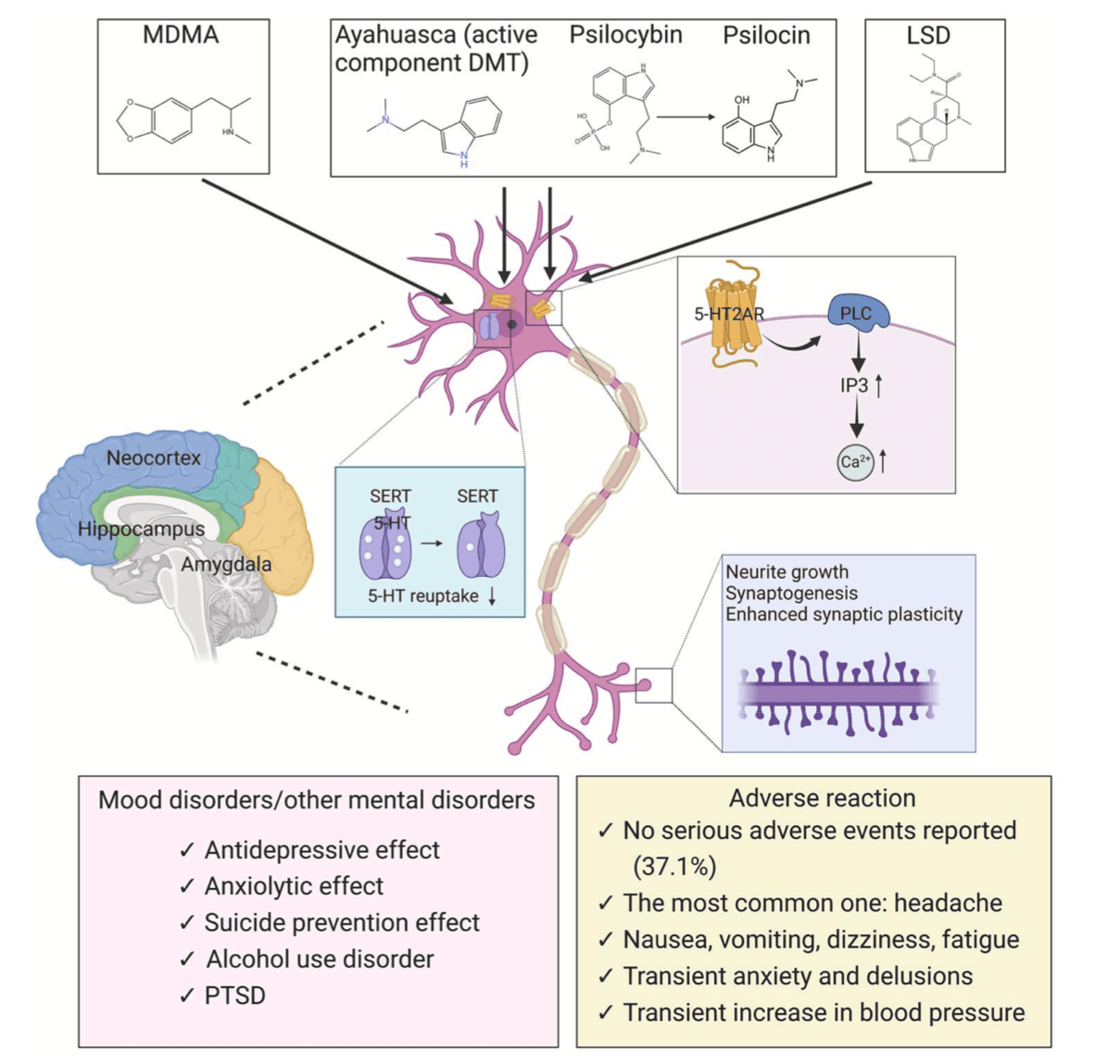

However, we have a limited understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of psychedelic compounds, their therapeutic potential at scale, and whether their positive outcomes can be separated from undesirable effects (Hess and Gould, 2023). Most studies suggest that psychedelics are 5-HT2A receptor agonists that can lead to profound changes in brain regions such as the hippocampus, neocortex, and amygdala, which are related to perception, cognition, and mood (Kwan et al., 2022). Downstream effects of the 5-HT2A receptor activation on cytomembranes, activation of phospholipase C (PLC), and subsequent synergistic inositol trisphosphate (IP3) activation ultimately lead to increased intracellular calcium concentration and altered neuronal firing (Mastinu et al., 2023). Nevertheless, there are common and subtle differences in the mechanisms of action of different psychedelics (Fig. 7). LSD acts as a 5-HT1A receptor agonist in the nucleus of the locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei (Reissig et al., 2005). MRI scans of the brains of volunteers taking LSD showed surprisingly enhanced neuroactivity with more brain blood flow, higher electrical activity, and denser network communication patterns (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016b). In addition, LSD is thought to be a partial agonist of 5-HT2A receptors, particularly those expressed on neocortical pyramidal cells (González-Maeso et al., 2007).

Ayahuasca, a botanical hallucinogen traditionally used by indigenous groups of the Northwest Amazonregion for ritual and medicinal purposes, has a hallucinogenic impact because it contains a mixture of two plants: the ayahuasca vine Banisteriopsis Caapi (inhibit monoamine oxidase) and the chakruna shrub Psychotria Viridis(containing DMT) (Mastinu et al., 2023). Most of the literatures about ayahuasca we included described the dosage of DMT, but only one mentioned ayahuasca without elucidating the specific dosage of DMT (Table 2). DMT is a partial agonist of the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors (5-HT2) and its mechanism of action involves the second messenger pathway of phospholipase C and A2 in postsynaptic neurons (Barker, 2018). It can also function at the presynaptic level as an inhibitor of the serotonin transporter(SERT) and vesicular monoamine transporter (2VMAT2) (Carbonaro and Gatch, 2016; Cozzi et al., 2009). Some recent studies have found a similar potential might exist for the short-acting tryptamine 5‑methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT). 5-MeO-DMT has shown potent and ultra-rapid antidepressant effects and produced significant changes in inflammatory markers, improved affect, and non-judgment (Reckweg et al., 2023; Uthaug et al., 2020). Our study focused on oral administration of traditional ayahuasca, rather than inhalation of vaporized synthetic 5-MeO-DMT. More clinical trials are needed to confirm the anti-inflammatory and antidepressant effects of synthetic 5-MeO-DMT.

Psilocybin has a good affinity with the 5-HT2A receptor (Erkizia-Santamaría et al., 2022) and has been shown to have pharmacological effects by increasing neuroplasticity and neurogenesis via the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways (Abate et al., 2020). Recent studies have demonstrated that activation of intracellular 5-HT2ARs by DMT and psilocin(produced from psilocybin) leads to sustained increases in dendrite growth and spine density (Hess and Gould, 2023). The prosocial therapeutic effects of MDMA underlie its mechanisms for treatment-resistant mental illness. MDMA is a 5-HT2A receptor agonist, and this effect is thought to contribute to its induced release of DA in the mesolimbic system (Orejarena et al., 2011). MDMA acting on the SERT is necessary but not sufficient for the prosocial effects of MDMA, which also requires 5-HT1B receptor activation (Heifets et al., 2019). MDMA also increases the available concentration of 5-HT via inhibiting SERT, reversing the direction of the membrane transporter and ultimately resulting in the accumulation of 5-HT in the synaptic cleft (Verrico et al., 2007). On the other hand, MDMA promotes the release of monoamines, hormones (oxytocin, cortisol), and other downstream signaling molecules (e.g., BDNF) that dynamically modulate emotional memory circuits (Feduccia and Mithoefer, 2018). In summary, the pharmacology and complexity of mechanisms of action may explain the variability of treatment effects, and further research is needed for clarification.

Although definitive clinical efficacy of psychedelic therapy for depressive and anxiety symptoms has not yet been demonstrated, our review demonstrates that psychedelics show promise against negative emotions within various pathological conditions such as MDD, TRD, terminal disease related negative emotions, SUD, PTSD and social anxiety disorder. Negative emotions like anxiety and depression exist in many people and are manifested in varying severity within many psychiatric disorders. The FDA designated psilocybin as a breakthrough therapy for the treatment of MDD and TRD based on results from a Phase II clinical study released in April 2023. Psilocybin at a single dose of 25 mg, but not 10 mg, reduced depression scores significantly more than a 1-mg dose over a period of 3 weeks but was associated with adverse effects in a phase 2 trial (Goodwin et al., 2022). In addition, psychedelic-assisted therapy (e.g., ayahuasca) has shown promising results as a treatment for SUD (Giovannetti et al., 2020). Other studies have shown that psilocybin has a rapid and long-lasting effect on anxiety and depression in many cancer patients (Agin-Liebes et al., 2020; Griffiths et al., 2016; Grob et al., 2011; Ross et al., 2021, 2016). Psilocybin and LSD administered in combination with psychotherapy also produced robust decreases in the severity of alcohol addiction compared to placebo and psychotherapy (Bogenschutz et al., 2022; Krebs and Johansen, 2012). Additionally, a phase III clinical trial found that MDMA coupled with psychotherapy was twice as likely as placebo with psychotherapy to induce recovery from PTSD (Mitchell et al., 2021). These early successes indicate an urgent need for more large-scale clinical trials to confirm clinical efficacy and document any adverse effects of psychedelics in assisted therapies.

Our meta-analysis showed significant negative symptom reduction at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, although the efficacy may weaken over time. A long-term follow-up of 3.2 and 4.5 years after psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy in patients with life-threatening cancer conducted by Stephen Ross indicated sustained efficacy of psilocybin treatment (Ross et al., 2021). We suggest that the underlying neural mechanisms behind this may involve remodeling and persistent changes in functional brain networks. Psilocybin can produce a therapeutic response in patients with refractory depression by increasing the connectivity of functional brain networks (Daws et al., 2022). These significant changes in the structure of brain modules suggest that the immediate effects of psilocybin may be retained. In support of this suggestion, a single dose of psilocybin can persistently induce the formation of dendritic spines in the medial frontal cortex of mice and enhance neuronal connectivity (Shao et al., 2021). This synaptic structural remodeling occurred within 24 h and persisted even after 1 month, potentially providing a long-term integration of experiences and lasting beneficial actions.

The increased risk of suicide in patients with MDD or other mood disorders contributes to high mortality and morbidity rates, and reducing the risk of suicide using psychedelics is quite compelling. Lifetime psilocybin use was associated with lowered odds of lifetime suicidal thinking, planning, and attempts (Jones et al., 2022). Another study showed ayahuasca reduced suicidal ideation (Zeifman et al., 2019). Ketamine also shows rapid antidepressant effects which reduce suicidal ideation (Abbar et al., 2022; Beaudequin et al., 2021; Mkrtchian et al., 2021). However, only two articles evaluating suicidal ideation were included in this meta-analysis, and broader demographic circumstances need to be considered in future studies to make this finding representative.

Although most studies indicate that psychedelic therapy has not resulted in serious life-threatening adverse effects, questions about the safe use of psychedelics remain. For example, Goodwin et al. conducted a phase 2 double-blind trial using single-dose psilocybin for TRD and found that in 233 participants adverse events occurred in 84% of participants in the 25 mg group, 75% of participants in the 10 mg group, and 72% of participants in the 1 mg group (G.M. Goodwin et al., 2023a). In a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of psilocybin involving patients with moderate-to-severe MDD, 87% of patients in the psilocybin group had adverse events (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021). Moreover, adverse events in polydrug ecstasy users with good medical health received MDMA 75 mg in two test days, and MDMA aggravated rather than relieved two negative affect states, anxiety and confusion (Kuypers et al., 2018). A syndrome known as hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is defined by persistent or recurrent perceptual symptoms that resemble the acute effects of hallucinogens after repeated use of hallucinogens. A wide range of LSD-like substances, cannabis, MDMA, psilocybin, mescaline, and psychostimulants are linked to HPPD (Lev-Ran et al., 2017; Müller et al., 2022; Orsolini et al., 2017). This makes special and secure therapeutic settings essential for intended therapeutic outcomes when using psychedelics. An exploratory survey about psychedelic knowledge and opinions in psychiatrists showed that the most desired topics were potential benefits of psychedelic-assisted therapy, how to conduct psychedelic-assisted therapy, psychedelic pharmacology, and psychedelic side effects (Barnett et al., 2022). Ideally, psychedelics can be utilized as powerful vectors of interpersonal psychotherapy (Ponomarenko et al., 2023), but administration of psilocybin requires careful attention to the setting in which the drug is administered (Messell et al., 2022). MDMA is believed to enhance a therapeutic alliance, thereby facilitating therapist-assisted trauma processing (Sottile and Vida, 2022). MAPS Public Benefit Corporation (“MAPS PBC”) announced submission of new drug application to the FDA for MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD. If approved, it would be the first psychedelic-assisted therapy approved for PTSD.

It has become evident from over 50 years of illicit hallucinogen use that combining psychedelics with psychotherapy under strict physician supervision is safer than unsupervised long-term use with abuse potential. Moreover, studies in recent years also have shown promising results regarding the use of psychedelics in addiction. For example, psilocybin may be a potentially efficacious adjunct to current smoking cessation treatment models (Johnson et al., 2014, 2017). Furthermore, LSD, MDMA, and psilocybin all have shown therapeutic effects in patients with alcohol use disorder or alcoholism (Bogenschutz et al., 2022; Krebs and Johansen, 2012; Ludwig et al., 1969; Sessa et al., 2021). In addition, we summarized the effects of psychedelics in healthy populations (Supplementary Table 2). It was found that 28 out of a total of 37 studies reported positive effects, which included subjective positive effects such as increased positive mood, prosocial behavior, happiness, social relationships, evaluation of the self, anxiolysis, protracted analgesic effect and attenuation of symptoms related to hopelessness and panic-like symptoms; 2 of them reported non-significant results (no improvement or effect on mood); 8 of them mentioned negative effects such as impaired recognition and accuracy of sad and fearful faces, prolonged REM sleeplatency, increased anxiety and confusion, and attenuates the encoding and retrieval of salient details from emotional events (75% derived from MDMA, but it is worth noting that some of the studies also reported positive effects); the other 3 used neutral descriptions such as producing subjective effects, and were well tolerated. In general, psychedelics are well tolerated in healthy populations, but attention should be paid to the negative effects mentioned above. Further research is warranted to define potential indications and safety guidelines.

There are several limitations in this meta-analysis. First is the main problem of heterogeneity, with different types of clinical studies being included and large variations in the doses, regimens, samples, inclusion criteria, and primary endpoints used in different studies. Second, meta-analysis cannot avoid publication bias, which occurs because positive results are more likely to be published, which can significantly overestimate effect sizes. We have excluded all observational studies to minimize this bias. Third are small study sample sizes, improper methodological design, inadequate statistical analysis, and subject inclusions. Among all the articles, 33 studies have less than 30 subjects, resulting in the lack of significant correlations in the meta-regressions. Fourth, because psychedelics can significantly alter perception and even produce hallucinations, the failure of some studies to blind participants and staff may have resulted in biased estimates of effects, making it difficult to ensure the certainty of our evidence. Finally, functional unblinding may still be challenges for researchers attempting to design rigorous, blinded, clinical trials. Placebo effects may be inflating efficacy sizes and psychotherapy trials would similarly have high rates of functional unblinding given how dramatically different these interventions are subjectively experienced by trial participants (Rosenblat et al., 2023). Thus, more cautious, large-scale, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials of psychedelics are essential.

In conclusion, the present study provides a relatively comprehensive insight into the efficacy and adverse effects of psychedelics in populations with eight types of mental disorders. Our findings suggest that psychedelic-assisted treatment offers a promising new direction for the booming innovations in the treatment of mental disorders. However, treatment with psychedelics still carries some risk of adverse effects and abuse, so the combined use of psychedelics as an adjunctive therapy under the strict supervision of a physician is certainly advisable.