Abstract

Background: Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) are chronic conditions characterized by high relapse rates and significant psychological, physical, and social complications. Despite the availability of traditional pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions, many individuals struggle to maintain abstinence. Recently, physical activity (PA) has emerged as a promising complementary intervention. This review aims to examine the existing evidence on the effects of PA in individuals with SUDs, with a particular focus on neurobiological mechanisms.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted on 30 September 2024, searching relevant keywords on PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus. Randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, reviews, and meta-analyses published between 1988 and 2024 were considered.

Results: Fifty studies were included. Key themes included the role of PA in inducing neuroadaptation in individuals with SUDs, which is crucial for relapse prevention and impulse control, and the effects of PA depending on the type of PA and the specific SUD. Neurobiological modifications related to PA are of particular interest in the search for potential biomarkers. Additionally, studies explored the effects of PA on cravings, mental health, and quality of life. The review overall discusses the psychological changes induced by PA during SUD rehabilitation, identifies barriers to participation in PA programs, and suggests clinical and organizational strategies to enhance adherence.

Conclusions: Physical activity is a promising adjunctive therapy for the management of Substance Use Disorders. Long-time longitudinal studies and meta-analyses are needed to sustain scientific evidence of efficacy. The success of PA programs moreover depends on overcoming barriers to adherence, including physical, psychological, and logistical challenges.

1. Introduction

Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) represent a critical challenge in global public health, with far-reaching consequences for individuals, families, and societies. According to Volkow and Blanco [1], SUDs are characterized by chronic, relapsing patterns of compulsive substance use, often accompanied by significant impairments in physical, psychological, and social functioning [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights that the global burden of SUDs continues to grow, exacerbating healthcare costs, disability rates, and socioeconomic disparities worldwide [2].

While traditional treatment approaches, including pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, have proven effective for many, they often fail to address all facets of SUDs, particularly the integration of physical and behavioral health. Relapse rates remain a significant concern, underscoring the need for innovative and holistic interventions that support long-term recovery [3]. Recent advancements in understanding the neurobiological and psychosocial aspects of SUDs have prompted interest in complementary therapies, such as physical activity (PA), as part of a broader treatment strategy.

PA offers a multifaceted approach to recovery, targeting both neurobiological and behavioral pathways. Evidence shows that regular PA enhances neuroplasticity and modulates the brain’s reward system, which is often dysregulated in individuals with SUDs [4]. The literature proposes that exercise can act as a novel treatment for drug addiction by alleviating withdrawal symptoms, reducing cravings, and improving mood through its effects on dopamine regulation and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [4]. Furthermore, studies suggest that PA positively impacts anxiety and depression, which frequently co-occur with SUDs, thereby addressing critical comorbidities that hinder recovery [5,6]. Notably, Giménez-Meseguer et al. reported that exercise tailored to the needs of individuals with SUDs significantly improved their physical health, mood, and psychological well-being, thus highlighting its relevance as a holistic therapeutic tool [7]. Animal studies have also provided insights into the mechanisms underlying PA’s benefits. For example, research on morphine-dependent and ethanol-withdrawn rats demonstrates that voluntary exercise can mitigate anxiety and seizure susceptibility, highlighting the neuroprotective role of PA in addiction recovery [6,8]. These findings provide a foundation for exploring how PA interventions can complement existing treatments and offer new avenues for addressing the complexities of SUDs.

This review aims to evaluate evidence supporting PA as an adjunctive therapy for SUDs, focusing on its neurobiological mechanisms, therapeutic benefits, and practical implications for clinical and community settings. By examining the interplay of physical, psychological, and social factors, this review seeks to advance the understanding of PA’s role in promoting recovery and long-term well-being for individuals with SUDs.

The review is structured as follows: first, we examine the neurobiological mechanisms through which PA benefits individuals with SUDs. Next, we discuss specific PA interventions and their efficacy in different contexts. Finally, we analyze barriers to implementation and offer recommendations for integrating PA into clinical and community settings.

2. Results

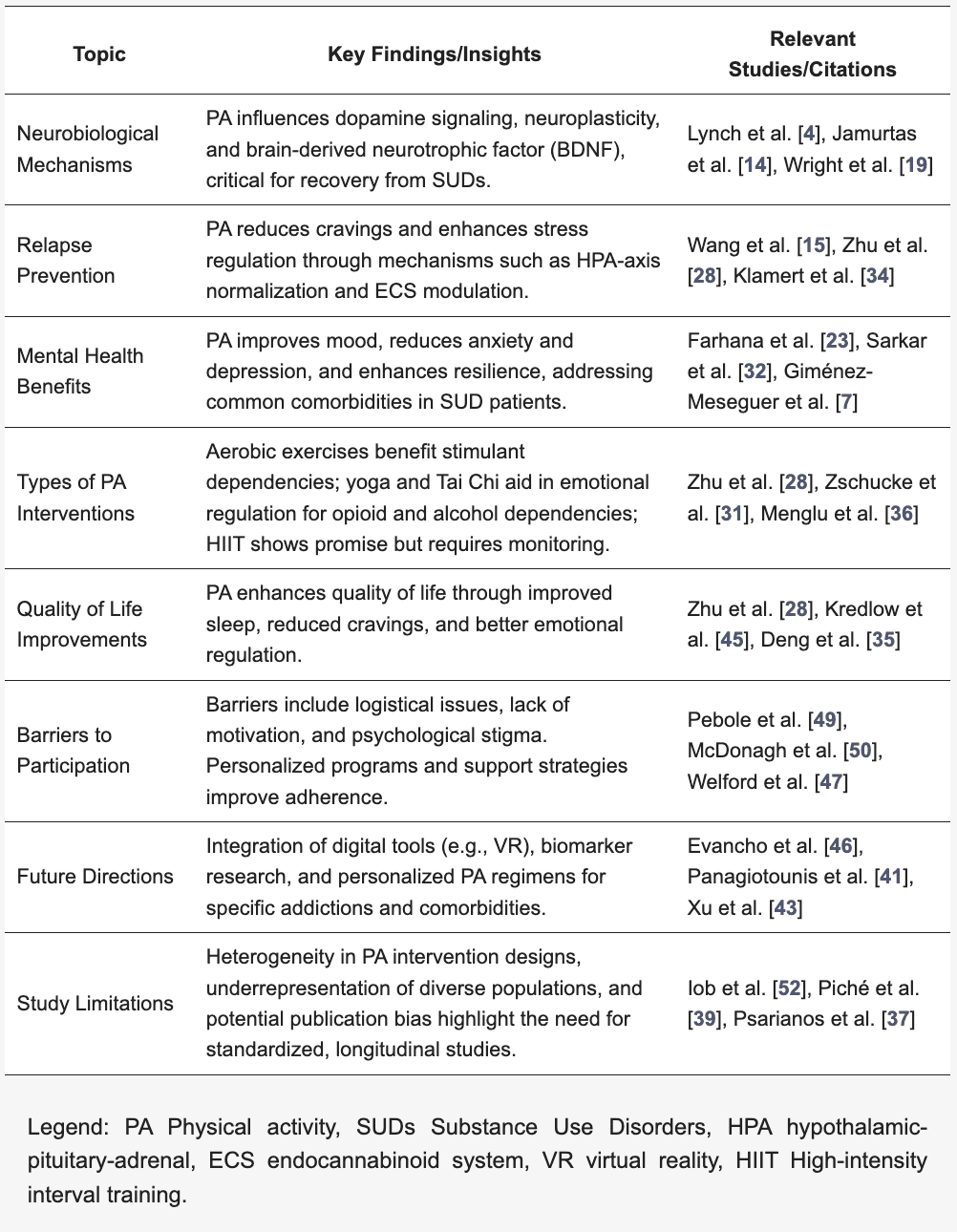

A total of 50 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review. Results were grouped thematically (Table 1) and further comprehensively discussed, focusing on barriers and strategies for enhancing adherence to PA and future research.

Table 1. Thematic synthesis of the review with key findings.

2.1. Neurobiological Mechanisms and Brain Plasticity

The beneficial effects of PA on SUDs are supported by neurobiological mechanisms involving dopamine and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), both crucial for neuronal plasticity [9,10,11,12,13]. Lynch et al. [4] hypothesize that PA modulates dopaminergic signaling in the brain, promoting neuronal adaptations that help counter the effects of substances. Physical exercise positively impacts brain circuits associated with reward and pleasure, as demonstrated by Jamurtas et al. [14], who observed increased beta-endorphins and mood improvement in subjects with SUD. Additionally, PA reduces cortisol release, the stress hormone, supporting healthier stress regulation and helping to reduce anxiety, a known relapse trigger [15,16]. Furthermore, the normalization of dopaminergic and glutamatergic activity facilitated by exercise may aid in long-term relapse management [17,18].

An exciting frontier in PA research is the exploration of neurobiological markers that can predict an individual’s response to exercise. Understanding the genetic, epigenetic, and molecular mechanisms that underlie individual differences in exercise-induced neuroplasticity could help personalize PA programs for optimal therapeutic effects. Additionally, neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI could be used to observe real-time changes in brain activity and structure in response to exercise, offering deeper insights into how PA influences brain function in patients with SUDs [19].

2.2. Effects on Abstinence and Craving Symptoms

One of the most studied effects of PA in SUDs concerns its ability to reduce craving and withdrawal symptoms [20,21,22]. The meta-analysis by Wang et al. [15] demonstrated that moderate and intense PA programs can significantly increase abstinence rates, with positive effects also observed on physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms, such as irritability, insomnia, and anxiety. Longitudinal studies indicate that PA contributes to reduced relapse rates both in the early months and beyond, suggesting a lasting impact on maintaining abstinence [23,24].

2.3. Benefits of Mental Health and Quality of Life

PA is associated with significant improvements in mental health and quality of life in SUD patients. Farhana et al. [23] report that PA-based interventions, such as aerobic exercises and yoga, reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, improve mood, and reduce the likelihood of relapse [25,26,27]. A study by Zhu et al. [28] demonstrated that a group aerobic exercise program improved cognitive functions and emotions in SUD patients.

These effects are attributed to increased levels of endorphins and serotonin, which can enhance emotional well-being [29,30]. Mind-body exercises like Tai Chi have also proven effective in improving emotional regulation, thereby increasing psychological resilience.

2.4. Differences Among Types of Physical Activity and Their Efficacy in SUDs

The type and intensity of PA play a key role in treating SUDs. Aerobic exercises like running and cycling help reduce cravings for stimulants such as cocaine by boosting dopamine and serotonin levels [4,15]. Mind-body activities like yoga and Tai Chi improve emotional regulation and reduce anxiety, making them effective for opioid and alcohol dependencies [31,32]. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) shows potential for neuroplasticity recovery due to increased BDNF levels but requires careful monitoring [4]. A personalized approach that adapts PA to the patient’s needs and recovery stage is essential for optimizing treatment outcomes [33].

3. Discussion

Beyond its physiological effects, PA offers a range of psychological benefits for individuals with SUDs that can be essential in supporting the recovery process. These benefits include increased resilience, enhanced self-efficacy, strengthened emotional regulation, and an overall reduction in stress and anxiety symptoms, all of which play a crucial role in managing and preventing relapse [34,35,36].

Resilience, the ability to cope with difficulties and adapt positively to stressful situations, is an essential aspect for those seeking to overcome addiction. Studies show that PA can help build and strengthen resilience, improving a patient’s ability to face the psychological challenges characteristic of the withdrawal process [34]. This helps patients become more resilient to stressors and develop healthier coping mechanisms than those triggered by substance use [4]. The resilience developed through PA is not merely an immediate effect: long-term studies suggest that as patients continue regular PA, their resilience tends to consolidate [34,37]. This is particularly important for relapse prevention, as resilience helps patients navigate high-risk situations without resorting to destructive behaviors.

PA also contributes to improving self-efficacy, defined as a person’s confidence in their ability to perform specific actions to achieve certain results. PA requires discipline, specific and measurable goals, and progressive performance improvements, all of which strengthen self-confidence [35]. During recovery, patients with a high level of self-efficacy are more likely to believe in their ability to maintain abstinence and face daily challenges without resorting to substance use. PA allows patients to experience tangible progress, such as improvements in endurance or physical strength, which can easily translate into a broader perception of their capabilities, including control over their dependency. Progressive exercise programs, where incremental goals are set and achieved, foster self-efficacy and increase motivation, empowering patients to feel in control of their recovery.

One of the most immediate and well-documented psychological benefits of PA is its ability to reduce anxiety and stress, common and aggravating factors in SUDs. Anxiety can increase relapse risk and often represents one of the primary reasons patients turn back to substances. PA helps reduce cortisol levels and stimulates endorphin release [15]. Mind-body activities like yoga and Tai Chi have proven effective in reducing anxiety levels in SUD patients.

Zhu et al. demonstrated that Tai Chi interventions significantly improved sleep quality and emotional regulation in female patients recovering from amphetamine-type stimulant dependence. These long-term benefits contribute to reduced cravings and relapse risk, emphasizing the importance of incorporating mind-body activities into rehabilitation programs [38].

These activities combine physical movement with breathing and mindfulness techniques, allowing for deep relaxation. These exercises not only improve the patient’s emotional state in the short term but also increase awareness of their emotional responses, promoting more effective stress management.

PA can also enhance emotional regulation, helping patients respond adaptively to stressful situations rather than resorting to substances as a coping mechanism. Activities like jogging, brisk walking, and low-impact aerobics sessions have been linked to reduced impulsivity and improved emotional control [28]. Additionally, mindfulness training through activities such as yoga can help patients become more aware of their emotions and bodily states, reducing impulsivity and facilitating a calmer, more reflective response to daily challenges [25,26,27,37]. This is particularly beneficial for patients with alcohol or opioid dependencies, who tend to have impaired emotional regulation and are at a higher risk of relapse during times of elevated stress.

PA, through its positive effects on mood and energy, can also enhance patients’ intrinsic motivation to maintain abstinence [33]. Farhana et al. [23] observed that patients who incorporate PA into their treatment programs report higher levels of motivation to continue their therapeutic journey and maintain a healthy lifestyle. PA not only makes patients more proactive but also reduces symptoms of anhedonia and apathy, which are common depression symptoms associated with SUDs. Acting as a natural antidepressant, PA stimulates the release of positive neurotransmitters and enhances neurogenesis, counteracting depressive symptoms and reducing the likelihood of relapse during periods of low mood and isolation.

Another indirect psychological benefit of PA is the improvement in sleep quality. Sleep disturbances are common among SUD patients, as chronic substance use can disrupt circadian rhythms and impair rest quality [39]. Poor sleep increases relapse risk, leaving patients more vulnerable and less resilient to stressors. PA, particularly aerobic exercises, has been shown to improve sleep quality, contributing to overall psychophysical well-being and reducing relapse risk.

Concerning neurobiological mechanisms, neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections in response to learning, experience, or environmental changes. This process is essential for recovery in individuals with SUDs, as substance abuse often alters the brain’s reward system, particularly in areas such as dopamine pathways, the prefrontal cortex, and the nucleus accumbens. These changes contribute to the dysregulation of reward processing and increased susceptibility to cravings, stress, and relapse [34]. The beneficial effects of PA on SUDs are supported by neurobiological mechanisms involving dopamine and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), both of which are crucial for neuronal plasticity [9,10,11,12,13]. BDNF is known to facilitate the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses, especially in regions that are vulnerable to the damaging effects of substance abuse, such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Physical activity, especially moderate to intense aerobic exercise, has been shown to enhance PFC function by promoting the release of BDNF and improving synaptic plasticity in this critical area.

Studies indicate that PA reduces cravings by decreasing the hyperactivity of brain regions associated with reward processing, such as the nucleus accumbens [40].

These changes are important for relapse prevention, as the ability to manage emotional responses and make well-informed decisions is vital for maintaining abstinence and resisting the temptation of substance use [23].

Drugs of abuse often cause a massive surge of dopamine in the brain’s reward centers, leading to feelings of euphoria and reinforcing addictive behavior. Over time, however, the brain’s natural reward system becomes less responsive, requiring larger amounts of the substance to achieve the same effect. This phenomenon, known as dopamine dysregulation, contributes to the compulsive nature of addiction [34].

Exercise has been shown to restore balance in the dopaminergic system, particularly through the enhancement of dopamine receptor sensitivity and the release of dopamine itself. Regular PA helps re-establish healthier reward circuits by increasing dopamine transporter activity and promoting the release of dopamine in areas like the striatum, which is involved in both reward and motor functions [23]. Physical exercise positively impacts brain circuits associated with reward and pleasure, as demonstrated by Jamurtas et al. [14], who observed increased beta-endorphins and mood improvement in subjects with SUD.

Another innovative aspect of PA’s neurobiological effects is its influence on the endocannabinoid system (ECS), which is involved in regulating mood, pain, reward, and stress [19]. The ECS plays a crucial role in modulating the brain’s response to addictive substances and is implicated in both the reinforcing and anti-reward effects of drugs.

Physical activity has been found to increase the levels of endocannabinoids such as anandamide and 2-AG, which bind to cannabinoid receptors in the brain, particularly in regions associated with stress and emotional regulation.

Exercise-induced activation of the ECS may explain the reduction in stress and anxiety often reported by individuals engaging in PA, as well as its role in attenuating cravings. This mechanism is particularly relevant for individuals recovering from SUDs, as dysregulated stress response systems and heightened anxiety are common triggers for relapse. These mechanisms also underscore the potential for PA to mitigate stress-related triggers of relapse and enhance emotional regulation, particularly in populations with heightened anxiety or comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [41].

By modulating the ECS, PA not only supports emotional stability but may also reduce the negative emotional states that often accompany withdrawal and recovery.

One of the most compelling ways in which PA influences brain plasticity is through its effects on stress-related pathways, particularly the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Chronic substance use leads to an overactive HPA axis, which results in heightened cortisol levels, impairing emotional regulation and making the individual more vulnerable to relapse [19]. Furthermore, physical activity can complement other therapeutic interventions, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), by enhancing cognitive and emotional regulation [37]. The synergistic effects of combining PA with psychological therapies may lead to more robust outcomes in terms of relapse prevention and long-term recovery. Importantly, the neuroplastic effects of PA are not limited to short-term improvements; the brain’s capacity for change remains a dynamic process that continues to evolve with sustained exercise over time, offering ongoing benefits for individuals in recovery.

Moreover, the promotion of neuroplasticity through mechanisms like increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels not only aids in cognitive recovery but also supports emotional resilience. These changes underscore the importance of incorporating exercise into SUD therapy to address both the physiological and psychological aspects of recovery [42].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the application of biomarkers and innovative technologies to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of therapeutic programs for SUDs. The use of biomarkers such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and dopamine transporter activity levels has shown potential in personalizing physical activity (PA) interventions to optimize their neurobiological benefits. Additionally, emerging tools like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neurofeedback systems enable real-time monitoring of brain adaptations during PA-based rehabilitation, offering insights into the individual variability in treatment responses [8,13,40].

Beyond neurobiological biomarkers, advanced technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are being explored as complementary tools in SUD rehabilitation. These technologies create immersive environments that can simulate real-world triggers, allowing patients to practice adaptive responses while engaging in PA. For example, VR-based interventions have been effective in reducing cravings and improving emotional regulation by combining cognitive-behavioral strategies with physical engagement [19,37]. Incorporating these innovations into PA programs can help tailor interventions to individual needs, improve adherence, and provide scalable solutions for diverse patient populations. Future studies should focus on validating these tools in clinical settings, assessing their long-term impact on relapse prevention, and integrating them with traditional therapeutic approaches for a comprehensive rehabilitation model.

Concerning the choice of PA type and its intensity, studies show that it can play a critical role in the effectiveness of SUD treatment. Recent studies highlight how certain types of physical exercise may have specific effects depending on the type of dependency, patient recovery phase, and any psychiatric comorbidities. Aerobic exercises, such as running, brisk walking, swimming, and cycling, are among the most studied activities for their impact on SUDs, particularly for stimulant dependencies like cocaine and methamphetamines. These exercises are known for their ability to promote the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins, all key elements in countering cravings for psychoactive substances and improving mood [15]. Some studies suggest that aerobic exercise can mimic the dopamine spike typically triggered by drugs, providing a positive effect that helps reduce cravings and the risk of relapse [4].

Xu et al. reported a reduction in craving symptoms among methamphetamine-dependent participants following a 12-week moderate-intensity exercise intervention. This effect was accompanied by enhanced working memory, suggesting that cognitive improvements may contribute to better craving management and increased self-control [43].

Another advantage of aerobic exercises is their flexibility and accessibility: patients can practice them in structured facilities, such as gyms or outdoors. Additionally, their intensity can be adjusted based on the patient’s physical capabilities and motivation level, allowing for a personalized program that enhances adherence. However, since high-intensity aerobic exercises may not be suitable for patients with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions or mobility issues, it is important to select appropriate intensity and duration for each individual. Mind-body activities, such as yoga, Tai Chi, and Qi Gong, are emerging as particularly useful complementary tools for opioid and alcohol dependencies [44]. These exercises focus not only on physical movement but also on body awareness and breath regulation, making them ideal for helping patients develop better emotional management and greater interoceptive awareness [31].

Recent studies show that mind-body activities can reduce cortisol and promote a sense of calm and well-being. This effect is particularly beneficial for SUD patients dealing with comorbidities such as anxiety and PTSD, which are often present in opioid dependencies. In addition to enhancing psychological resilience, mind-body activities improve self-regulation capacity, a crucial quality for avoiding relapse [32]. Since many individuals with SUDs tend to react impulsively to craving stimuli, exercises like yoga and Tai Chi can teach response management techniques, helping to reduce impulsivity and respond more calmly to stressors.

It has been observed that patients participating in yoga programs for several weeks show reductions in craving scores and improvements in sleep quality, another factor that can help prevent relapse [23,45]. Although less studied in relation to SUDs compared to aerobic and mind-body exercises, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) programs are gaining interest for their potential to improve physical endurance and stimulate significant neurobiological changes, such as increased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which can support neuroplasticity and recovery of brain areas damaged by chronic substance use [4].

The benefit of HIIT programs for SUD patients appears to lie in their ability to stimulate a rapid endocrine response, promoting stress resilience and enhancing tolerance for physical and psychological discomfort. However, their high intensity may not be suitable for all patients, especially those with heart conditions or severe mental health issues. Nonetheless, when appropriately monitored, HIIT programs could offer unique benefits for patients who desire an intensive recovery pathway and are in good physical condition.

Considering the various effects of different types of PA on SUDs, the optimal treatment approach should be personalized, taking into account both the substance of dependence and the patient’s physical and psychological characteristics [34]. For example, in patients with alcohol and opioid dependencies, who often experience anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms, mind-body activities may prove particularly effective for long-term management. Conversely, for stimulant dependencies, where craving is prominent, regular aerobic exercises may be more effective in safely mimicking the neurobiological effects of substances, alleviating the desire for consumption.

A further benefit of a personalized approach is that it allows physical activities to be adapted to changes in the patient’s health status and psychological needs throughout recovery. Evidence suggests that an adaptive approach, in which patients start with mind-body activities and progress to higher-intensity programs as they gain strength and resilience, could optimize the therapeutic effectiveness of PA in SUDs.

Moreover, there is growing interest in combining PA with other cutting-edge therapies, such as neuromodulation techniques (e.g., transcranial magnetic stimulation) and pharmacotherapy, to enhance neuroplasticity and further support recovery [46].

Despite the promising evidence on the benefits of PA in SUD rehabilitation, publication bias remains a significant concern in this field. Studies predominantly focus on the positive outcomes of PA, potentially underreporting adverse effects or limitations. This bias may lead to an overly optimistic view of PA as an intervention, without adequately addressing the risks associated with certain psychiatric comorbidities. For instance, in individuals with bipolar disorder, PA might trigger manic or hypomanic episodes, especially with high-intensity regimens [1,34]. Considering the shared neurobiological underpinnings between SUDs and bipolar disorder, such as dopamine dysregulation, further investigation is needed to evaluate the safety and appropriateness of PA for these populations.

4. Limitations of the Current Literature

The body of research on the role of PA in the rehabilitation of individuals with SUDs has provided valuable insights; however, certain limitations must be acknowledged. One prominent issue is the variability in study methodologies, including differences in PA types, intensities, and durations, which complicate direct comparisons and the formulation of standardized treatment protocols [14,15,23]. Many studies rely on self-reported data for PA adherence and outcomes, introducing the risk of recall bias and overestimation of benefits [37].

Another limitation is the underrepresentation of diverse populations in research samples. Most studies focus on homogeneous groups, often excluding individuals with co-occurring mental health conditions or severe physical limitations, despite the high prevalence of such comorbidities in SUD populations [1,23,35]. Furthermore, the literature lacks robust evidence on the potential adverse effects of PA, especially for populations with specific vulnerabilities. For example, patients with bipolar disorder, who may share some neurobiological similarities with SUDs, could experience mood destabilization from certain types of exercise [34,37]. Additionally, the exploration of biomarkers and innovative technologies in PA research for SUDs is still in its infancy. While promising studies have begun to examine the use of neuroimaging and digital health tools for tracking treatment progress, these technologies are not yet widely adopted or validated in clinical settings [19,46]. This gap highlights the need for more longitudinal studies that integrate advanced technologies to provide objective and reproducible data on the long-term benefits and risks of PA interventions.

Lastly, publication bias may be a concern, as studies with positive results are more likely to be published, potentially skewing the perception of PA’s efficacy. Comprehensive meta-analyses that include unpublished and null-result studies could provide a more balanced understanding of PA’s role in SUD treatment [15,39].

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Search Strategy

Search was carried out on 30 September 2024 using main online academic databases. These were the databases consulted: PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the literature for this narrative review, the following keywords were utilized for each thematic area analyzed in the study. The search terms were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR) to refine the search results effectively: 1. Physical Activity and Substance Use Disorders, Keywords: “physical activity”, “exercise”, “substance use”, “substance use disorder”, “addiction”, “rehabilitation”, “therapy”, “recovery”, “treatment outcomes”, “addiction recovery”; 2. Neurobiological Mechanisms, Keywords: “dopamine”, “reward system”, “brain plasticity”, “neurotransmitters”, “endogenous opioids”, “stress regulation”, “neurobiological changes”, “craving reduction”, “executive function”, “neuroadaptation”; 3. Psychological Benefits of Physical Activity, Keywords: “stress management”, “mood enhancement”, “self-esteem”, “anxiety reduction”, “depression management”, “coping mechanisms”, “psychological resilience”, “behavioural activation”, “emotional regulation”; 4. Social Benefits of Physical Activity, Keywords: “social support”, “community engagement”, “peer support”, “social integration”, “group exercise”, “team sports”, “social networks”, “isolation reduction”; 5. Intervention Studies and Effectiveness, Keywords: “clinical trials”, “intervention studies”, “effectiveness”, “outcomes”, “exercise programs”, “structured physical activity”, “randomized controlled trials”, “observational studies”; 6. Comparative Approaches, Keywords: “physical activity vs. traditional therapies”, “multimodal approaches”, “combined interventions”, “exercise and pharmacotherapy”, “alternative treatments”, “comparative effectiveness”. Studies published from 1988 to 2024 and written in English were considered for screening.

5.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Criteria for inclusion were randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, reviews, and meta-analyses addressing physical activity in substance use disorder rehabilitation. Criteria for exclusion were single case reports with limited clinical applicability and studies focusing solely on pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatments or alternative treatments without PA integration. Abstracts, conference proceedings, and articles lacking full-text availability were also excluded.

5.3. Data Extraction

Initial screening was performed by the first author through the review of titles and abstracts. Full-text articles were subsequently reviewed based on the inclusion criteria. The most relevant articles were then selected based on the research field, which included the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the effect of physical activity on the rehabilitation of individuals with Substance Use Disorders, its effects on abstinence and craving, its impact on quality of life and mental health, the search for neurobiological markers, and the differences between various types of exercise and different psychoactive substances. Divergences were resolved through discussion with the other authors.

6. Barriers to Participation and Strategies to Enhance Adherence

Despite documented benefits, many SUD patients face difficulties in maintaining commitment to PA, often due to a lack of adequate facilities, social support, and motivation. Literature suggests that barriers may be physical, psychological, social, and logistical, with each aspect requiring specific intervention strategies to promote sustained participation [3,47]. Recent studies show that an approach based on personalized programs, education on PA benefits, and ongoing support can significantly improve adherence and treatment outcomes in SUDs [4,23,34].

Moreover, the variety of interventions analyzed underscores the importance of offering flexible, patient-centered programs that cater to diverse preferences and capacities [48].

Regarding psychological barriers, low motivation, poor self-esteem, and social anxiety are significant obstacles to participation in PA programs. SUD patients often exhibit symptoms of depression and apathy, which negatively impact motivation to engage in physical activity. Low self-esteem is also common and may lead patients to avoid PA due to fear of being unable to sustain regular activity or fear of being judged by others [49]. Social anxiety is particularly high among SUD patients, as many feel vulnerable in public or group settings, fearing comparison with others [19].

To overcome these barriers, psychological support and encouragement of self-efficacy are essential strategies. Orientation sessions can help patients set realistic goals and personalize their programs, reducing performance anxiety and increasing confidence in their abilities. Studies indicate that starting with low-intensity exercises in private settings or individual sessions can help alleviate social anxiety and ease patients into PA programs [15,25,50]. Additionally, motivation techniques such as progress tracking and positive reinforcement increase self-efficacy, encouraging patients to continue with the program [3]. To address psychological barriers such as stigma or lack of awareness about PA’s benefits, incorporating group-based interventions or mindfulness-focused activities like yoga has shown promise. These approaches not only foster community but also help mitigate resistance to treatment by creating a supportive environment [51].

Regarding physical barriers, many SUD patients suffer from chronic physical conditions due to prolonged substance use, which can limit their ability to engage in intense physical activities. Cardiovascular issues, respiratory problems, and muscle pain are common in this patient group, making it challenging to commit to activities requiring sustained effort. Physical withdrawal symptoms, such as fatigue and weakness, can also hinder regular participation in the first months of treatment [37].

To address physical barriers, it is essential to tailor PA programs to patients’ physical capabilities. Studies suggest that low-impact exercises like walking, swimming, and stretching are particularly effective for improving physical fitness without placing additional stress on the body [23]. McDonagh et al. [50] highlight that involving physical therapists or specialized trainers can help patients start safely, with a gradual and supervised PA program adapted to their physical abilities, thereby reducing the risk of dropout due to physical difficulties.

For many patients, limited access to sports facilities, lack of financial resources, and time constraints are significant logistical barriers. Financial difficulties are a particularly serious issue for those who have lost their jobs or face financial struggles due to addiction. Additionally, a lack of transportation or distance from sports facilities can limit participation [49]. Furthermore, for patients who need to balance treatment with work and family commitments, time is often a limiting factor that discourages them from engaging in PA [52].

To reduce logistical barriers, home-based programs and physical activities that do not require expensive equipment or specific spaces can be promoted. Studies show that exercises such as jogging, bodyweight exercises, and brisk walking are highly accessible and effective, requiring minimal investment [4]. Using monitoring apps and exercise video guides for home-based activities allows patients to participate flexibly, eliminating the need to attend expensive or distant facilities. For those with time constraints, shorter sessions distributed throughout the day can be recommended, allowing them to accumulate benefits even with minimal intervals of activity [15].

Lack of social support is also a crucial barrier for many SUD patients, who often live in isolation or have limited social networks. This isolation reduces motivation to participate in physical activities and increases the risk of early dropout [42]. Patients lacking support may struggle to maintain a long-term commitment, as they lack a supportive context to encourage them to pursue their recovery goals [18]. Wright et al. [18] suggest that small support groups within PA programs can provide patients with a safe space to share experiences and encourage each other, creating a supportive environment that enhances mutual commitment.

The participation of family members in PA activities, where possible, can also offer additional support, improving adherence and assisting the patient in their struggle against addiction [3]. An often underestimated barrier to participation is the lack of awareness of the benefits PA can bring to SUD treatment. Many patients view PA as an optional or secondary activity compared to other therapies, such as pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, and do not fully understand its potential positive effects on relapse prevention.

To increase awareness and motivation, the literature recommends integrating PA education into treatment programs, offering informative sessions on specific benefits such as reducing craving symptoms and positively impacting mood [50]. Patient testimonials and presentations of research findings can reinforce the perception of PA as an essential component of the recovery journey [34].

Additionally, without a regular monitoring and feedback system, many patients may easily lose motivation to participate in a PA program. The lack of feedback limits the perception of progress, making it easier for patients to drop out of the program [37]. Monitoring programs, such as using fitness applications or wearable devices, provide immediate feedback on progress and encourage patients to continue. Pebole et al. [49] highlight that regular monitoring and weekly feedback from healthcare providers significantly boost motivation and improve adherence to PA programs. Follow-up sessions with trainers can help patients maintain motivation and tailor programs to their physical and psychological needs, reducing the risk of early dropout [4].

7. Recommendations and Practical Implications

This review highlights the significant role of physical activity in the treatment and rehabilitation of individuals with Substance Use Disorders. Evidence demonstrates that PA improves physical, psychological, and behavioral outcomes, and translating these findings into actionable strategies for clinical and community settings is essential.

A key recommendation is that PA programs should be tailored to individual characteristics, such as the type of substance used, comorbidities, age, fitness level, and personal preferences. Personalized interventions enhance adherence and optimize therapeutic outcomes [33]. For instance, activities like yoga or walking may be more suitable for individuals with physical limitations, while running or strength training might be appropriate for those seeking greater physical challenges.

The integration of PA into multimodal treatment approaches, such as combining it with cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, or pharmacological treatments, offers promising results. Such combinations address the physiological and psychological dimensions of recovery, fostering a holistic pathway for individuals [5,20]. Furthermore, sustained engagement in PA programs can be supported through monitoring mechanisms, such as wearable devices or mobile applications, which provide real-time feedback and reinforce motivation [47].

In practical terms, PA should be systematically incorporated into SUD treatment programs in both clinical and community settings. Accessibility can be improved by offering low-cost or no-cost options, such as community walking groups or home-based exercise plans [21]. Facilities may also allocate resources for hiring exercise specialists or creating dedicated fitness spaces to support these initiatives.

Enhancing adherence to PA programs is critical and can be achieved by addressing common barriers such as a lack of motivation, limited access, and inadequate social support. Starting with low-intensity activities and gradually increasing the intensity builds confidence and prevents overexertion [21]. Group-based programs can create a sense of community, reduce isolation, and improve accountability, while incentive systems, such as rewards or recognition for achieving milestones, can further encourage participation [39]. Healthcare providers play a crucial role in promoting PA for SUD recovery. They should receive training on the benefits of PA and be equipped to address patient concerns, such as physical limitations or skepticism about its effectiveness [5].

Additionally, cultural and contextual adaptations are essential to ensure the relevance and acceptance of PA programs [28]. Incorporating traditional or region-specific activities can enhance engagement and foster greater acceptance among diverse populations. Sustaining these interventions requires collaboration among healthcare systems, community organizations, and policymakers [39]. Establishing long-term funding and prioritizing PA as a preventive and therapeutic tool in SUD treatment can embed these programs into standard care practices. Ultimately, these efforts promise to enhance the accessibility, adherence, and effectiveness of PA programs, significantly improving outcomes for individuals recovering from SUDs.

8. Future Research Directions and the Importance of Longitudinal Clinical Studies

To further consolidate the effectiveness of physical activity as an adjunct therapy for SUDs, longitudinal clinical studies are crucial to monitor long-term effects and fully understand the dose-response relationship between physical activity and patient outcomes. Such studies should explore not only the immediate effects of different PA modalities (aerobic, HIIT, yoga, etc.) but also the sustained benefits over time, particularly concerning relapse prevention and craving management [19,31].

Additionally, it would be valuable to test the integration of physical activity with other treatment modalities, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or pharmacological therapy, to assess the efficacy of combined approaches in managing SUDs. Specifically, the use of digital technologies for progress monitoring and program personalization could offer new opportunities for optimizing treatments. Future research should also focus on how to adapt PA programs to different types of addiction (e.g., alcohol, drugs, stimulants) and the specific psychophysical needs of patients, developing personalized therapeutic protocols that maximize benefits and reduce relapse rates [35,49].

Future research should also aim to address gaps in the literature by investigating potential adverse effects of PA in populations with psychiatric comorbidities, such as bipolar disorder. Rigorous randomized controlled trials are necessary to mitigate publication bias and provide a balanced understanding of both the benefits and risks of PA in diverse patient groups. Additionally, studies should explore personalized approaches that adapt PA regimens to the unique needs of individuals with co-occurring mental health conditions [23,30]. Incorporating innovative technologies, such as virtual reality and biomarker monitoring, could further enhance the safety and efficacy of these interventions like further revisions or enhancements.

9. Study Limitations

While this review highlights the therapeutic potential of PA in SUDs, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, as a narrative review, the study does not employ a systematic approach to data collection, which could introduce selection bias. This limitation is compounded by the inclusion of studies with diverse methodologies and heterogeneous populations, making it challenging to generalize findings. Secondly, most of the evidence comes from small-scale studies, limiting the applicability to broader clinical contexts. The variability in PA interventions, including differences in type, intensity, and duration, further complicates the synthesis of consistent conclusions. Additionally, the review largely focuses on the benefits of PA, with a limited exploration of potential adverse effects or contraindications for specific patient groups.

10. Conclusions

Physical activity is a promising and potentially effective adjunct therapy for managing Substance Use Disorders, contributing to improved mental health and quality of life, reduced craving symptoms, and relapse prevention. Evidence suggests that PA has direct effects on the brain, which are crucial in counteracting the chronic effects of substances, as well as for developing specific biomarkers of efficacy. The continued evolution of research and the application of innovative technologies are essential to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of these therapeutic programs, with the aim of promoting more comprehensive and lasting rehabilitation for patients with Substance Use Disorders.

The success of PA programs largely depends on addressing barriers that limit adherence, including physical, psychological, and logistical obstacles, boosting patient motivation and PA accessibility. This also means organizing the social and health services for addiction care with regard to this evidence, thus meeting the needs of health prevention and social integration.

Exploring ways to adapt PA programs to different types of addiction and the specific psychophysical needs of patients will pave the way for personalized protocols that could maximize therapeutic benefits and significantly reduce relapse rates, contributing to a holistic and sustainable therapeutic approach.