Abstract

Research suggests that the presence of peers influences adolescent risk-taking by increasing the perceived reward value of risky decisions. While prior work has involved observation of participants by their friends, the current study examined whether observation by an anonymous peer could elicit similarly increased reward sensitivity. Late adolescent participants completed a delay discounting task either alone or under the belief that performance was being observed from a neighboring room by an unknown viewer of the same gender and age. Even in this limited social context, participants demonstrated a significantly increased preference for smaller, immediate rewards when they believed that they were being watched. This outcome challenges several intuitive accounts of the peer effect on adolescent risk taking, and indicates that the peer influence on reward sensitivity during late adolescence is not dependent on familiarity with the observer. The findings have both theoretical and practical implications for our understanding of social influences on adolescents’ risky behavior.

Introduction

One of the most prominent features of adolescence is an increased propensity for individuals to engage in risky behavior. Individuals in this stage of life are far more likely to engage in unprotected sex, criminal behavior, reckless driving, and experimentation with legal and illegal drugs than at any other time during the lifespan (Casey, Jones & Hare, 2008; Steinberg et al., 2008). Risk-taking among adolescents is notable not only for its frequency, but also its distinct social quality. Adolescents typically commit risky and delinquent acts in peer groups, whereas adults more frequently do so alone (see Albert & Steinberg, 2011, for a review).

Findings indicating that adolescent risk taking is especially likely to occur with peers are not surprising in light of the fact that individuals in this developmental period spend more time with peers than do adults (Csikszentmihalyi, Larson, Prescott, 1977). Accordingly, peer presence could simply coincide with risk taking, but not be a causally relevant factor. However, recent experimental evidence indicates that peer presence has a direct influence on decision making in adolescents that is not present among older individuals. For example, Gardner and Steinberg (2005) randomly assigned participants from three age groups – mid-adolescents (ages 13–16), late adolescents (18–22), and adults (24 and older) to play a video driving game either alone or with two friends in the room. Mid- and late adolescents who completed the task in the presence of peers took significantly more risks than those who performed the same task alone, an effect that was not seen among the adults.

Recent research utilizing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) provides some clues as to why this may be the case. Chein and colleagues (2011) used a paradigm similar to that used by Gardner & Steinberg (2005) to investigate the effects of peer presence on risk behavior while assessing differences in brain function across social context conditions and age groups. Adolescent participants (ages 14–18) in the scanner took more risks in a simulated driving game when they believed that two close friends were observing their behavior from an adjacent room and also exhibited relatively greater activation in the ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex when their peers were observing them than when they were alone. Increased activation in these brain structures, both of which are closely linked to the prediction and valuation of rewards (Ernst et al., 2004; McClure, Laibson, Loewenstein, & Cohen 2004), suggests that peer observation affects adolescents’ decisions about risk by increasing sensitivity to opportunities for reward. Chein et al. (2011) also found that adolescents and adults differed in the degree to which they engaged regions in the brain’s lateral prefrontal cortex, a region closely associated with executive functions and response inhibition, with adolescents engaging this region to a lesser degree across both social conditions.

This evidence is consistent with many other studies of brain development which have been interpreted through a so called “dual systems” account. The dual systems account explains adolescent behavioral tendencies in terms of the developmental interaction between a ventral reward system and a dorsal cortical control system (Steinberg, 2010), and variations of this integrative account have been posited by several research groups seeking to explain the developmental trajectory of risk behaviors (Chein et al., 2011; Galvan, 2010; Somerville, Jones & Casey, 2010). The reward system allows the brain to predict or estimate the value of potentially rewarding outcomes to behaviors (Cardinal, Parkinson, Hall & Everitt, 2002). Importantly, this system undergoes rapid developmental change in early adolescence (e.g., Laviola, Pascucci & Pieretti, 2001), leading to increased sensitivity to rewarding stimuli (Galvan, 2010; Leijenhorst, Moor, Op de Macks, Rombouts, Westenberg & Crone, 2010; Spear, 2009). This pattern of brain development coincides with greater behavioral reward sensitivity among adolescents relative to adults (Cauffman, Shulman, Steinberg, Claus, Banich, Graham et al., 2010). The combined evidence suggests that, around the time of puberty, the brain enters a period during which it is “wired” to assign greater salience to rewards during decision-making processes, potentially leading to impulsive and risky behavior. This reward bias diminishes with age, perhaps due to the maturation of cognitive control (Steinberg, 2010).

A shared characteristic of many risky behaviors exhibited during adolescence and early adulthood – smoking cigarettes, binge drinking, driving recklessly, and committing theft – is that they present an opportunity for an immediate (or near term) reward, either in the form of monetary, drug-related, or social rewards, but may also lead to negative long-term consequences (Casey, Jones & Hare, 2008; Galvan, 2008). The dual systems framework explains risk taking during this period by proposing that increased sensitivity to immediate rewards (which can be obtained by risky behavior) overwhelms a still maturing cognitive control system.

Applying this framework to young people making decisions in the presence of their peers, we propose that awareness of one’s peers further heightens sensitivity to immediate or near-term rewards, regardless of negative consequences and long-term considerations. This explanation is supported by neuroimaging findings indicating an increase in activation of reward-related regions in adolescents in response to social stimuli (e.g., Blakemore, 2008: Burnett & Blakemore, 2009; Guyer, McClure-Tone, Shiffrin, Pine, & Nelson, 2009).

Consistent with this account, research on temporal discounting shows that late adolescents’ preference for immediate rewards increases in the presence of their peers. Using a peer presence manipulation similar to that used in the Gardner & Steinberg (2005) study, O’Brien, Albert, Chein, and Steinberg (2011) examined delay discounting behavior in a late adolescent, undergraduate student sample (ages 18–20). We note that in that study, and in the present study, we construe this undergraduate age cohort as representative of a “late adolescent” sample, but acknowledge that individuals in the older half of these samples might also be referred to as young adults, and that possible differences in the nature of peer influences observed within different (and more fine-grained) age-bands comprising the period from early adolescence into young adulthood is an under-explored topic. In O’Brien et al (2011), participants were randomly assigned to complete a standard delay discounting task either with or without two friends present. The delay discounting task, a measure of preference for immediate versus delayed rewards, requires participants to choose between a smaller immediate monetary reward and a larger delayed one (e.g., $500 now vs. $1000 in 6 months). The tendency to subjectively discount delayed rewards has been linked to traits and behaviors that indicate a preference for immediate rewards, such as risk behavior and substance use, as well as a weak future orientation (Petry, 2002; Steinberg et al., 2009; Teuscher & Mitchell, 2011). In the O’Brien et al. (2011) study, participants in the peer condition displayed a greater preference for immediate rewards than participants who completed the task by themselves, as indicated by significantly lower average indifference points and higher rates of discounting. Like prior neuroimaging results (Chein et al., 2011), the findings from O’Brien et al. (2011) suggest that heightened sensitivity to immediate rewards is a possible mechanism underlying the increase in risk-taking behavior in the presence of peers.

In previous experimental studies exploring the peer effect on decision making (Chein et al., 2011; Gardner & Steinberg, 2005; O’Brien et al., 2011) the manipulation of social context involved peers who were close friends of the main participant. While this approach affords a degree of ecological validity, it also limits the potential to generalize the results to social situations where adolescents may not personally know the peers who are observing their behavior, such as in large public settings or on Internet websites. Using a somewhat different social context manipulation involving a virtual chatroom, Guyer and colleagues (2008) found that female adolescents showed increased activity in brain regions associated with emotion and reward processing when interacting with peers that they did not personally know, but who were deemed socially desirable. This finding points to the possibility that observation by individuals who are not close friends may also affect the salience of immediate rewards. This would suggest that the effect of peer presence on adolescent risk taking may not be limited to close friends. The current study seeks to further investigate this possibility.

An additional limitation of using real friends of the participant in the social context manipulation is that participants are likely to be affected by assumptions about their friends’ values, beliefs and opinions in their decision making. Furthermore, in studies where peers were in the same room as the participant, and were capable of communicating freely (e.g. Gardner and Steinberg, 2005; O’Brien et al., 2011), it was possible for the peers to overtly influence the participant (e.g., to explicitly suggest a risky or imprudent choice). O’Brien et al. (2011) acknowledged this issue, and suggested that an important goal of future research would be to rule out the possibility that explicit persuasion underlies the peer effect.

The current study was intended to address limitations of the previously used manipulations by examining whether observation by an anonymous peer can affect reward processing in a way similar to that observed in prior studies of adolescents and their friends, using a delay discounting paradigm. In this study, we utilize the previous peer-observation research paradigm, but with one crucial change: participants in the experimental condition are led to believe that they are being observed by an anonymous peer who is not present in the room. The use of an anonymous peer minimized the participant’s consideration of the observer’s values or opinions.

In creating this paradigm, we hoped to answer three distinct questions not adequately addressed in prior research. First, does the peer effect on adolescents’ reward processing occur in situations in which the peer is not personally known by the adolescent? Second, does the peer effect require the presence of multiple peers (as was the case in all previous studies), or can it be created with just one observer? Finally, must the peers be physically present in order to create the peer effect? Importantly, finding a peer effect under these conditions would indicate that none of these factors (familiarity with the observer, multiple observers, a physically proximal observer) is an essential component of, or necessary precondition for, the effect, but does not clarify whether these might be factors that moderate the effect (which could be a question for future research).

Method

Participants

The present sample included 64 participants, ages 18–22 (M= 19.3, SD=.98), drawn from an undergraduate student population at a large, urban university. Two additional participants provided data, but were excluded from analyses because their responses during debriefing indicated that they may not have believed the social context manipulation. While the sample contained individuals that ranged in age from 18 to 22, it should be noted that the majority of subjects (all but 5) were within the 18–20 age range.* All participants were recruited from psychology and marketing courses and received course credit in exchange for participation. Participants were randomly assigned to either an experimental (N=32) or control condition (N=32). The two groups did not differ in age, t(62)=.38, p=.71, gender, χ2(1)=.25, p=.62, race, χ2(3)=2.095, p=.55, or ethnicity, χ2(1)=.21, p=.88. The sample was 47% male and ethnically diverse (66% White, 19% Black, 14% Asian, and 2% Hispanic).

Procedure

Participants completed a battery of self-report measures and computer tasks as part of a larger program of research on adolescent decision-making.

Anonymous Peer Manipulation

After completing the questionnaires, participants were randomly assigned to either an alone or a peer-observer condition. In the alone condition, participants were explicitly told that no one would directly observe their performance. In the peer-observer condition, the participant was told that another student of the same gender and comparable age would be observing his or her task performance via a closed-circuit computer system, and would be making predictions about the participant’s performance on the computerized tasks. Participants were told that they would engage in a brief introduction over a two-way radio with the observer so that he or she could get some information that might help in making these predictions. In the exchange, the observer would provide a brief introduction of himself or herself, and the participant would respond by providing comparable information: his or her first name, age, year, and major, and the answers to two simple questions (“What is your favorite movie?” and “What is your favorite color”). It was explained that the purpose of the study was to see if the observing participant could make accurate predictions without physically meeting the observed participant. It was also indicated that the two participants would meet at the end of the study.

The introduction of the anonymous observer (in reality just a voice recording) occurred first, with the experimenter playing an audio recording over the two-way radio. A voice recording specific to the participants’ gender and age was used. Following the introduction of the observer, the participant introduced himself or herself according to the experimenter’s instructions. In addition to the experimenter’s verbal instructions, participants were given an instruction sheet that provided a template for what to say (see online supporting information).

Following the exchange, participants began a battery of three separate tasks. The task battery included a probabilistic gambling task, a delay discounting task, and a video driving task (always in that order). The current paper focuses on the findings from the delay discounting task. To remind the participant about the peer observer before each task, the experimenter asked, over two-way radio, if the participant was ready to begin the task, and subsequently asked the (nonexistent) observer if he or she was finished making predictions and ready for the participant to begin. The observer’s response, played over the two-way radio, was a simple confirmation after each task: “OK, I’m ready now”, “I’m good, go ahead”, and “I’m ready now”.

In the alone condition, participants completed the same task battery after being told that no one could directly observe their behavior on the task. Participants in both conditions were instructed that the experimenter would be waiting in a separate “control room” from which there was no access to the closed-circuit viewing system. To reinforce the belief that the experimenter was not an observer, in both conditions the participant had to leave the testing room and enter the experimenter’s room to notify the experimenter when it was time to set up each task. Following the study, all participants in the experimental condition were debriefed and fully informed of the deception and the true purpose of the study.

Task Procedure

The delay discounting task discussed in the current study was identical to the task used in O’Brien et al. (2011). In all trials, the value of the delayed reward was kept constant, at US$1000, and each trial began with a starting value of the immediate reward value of either US$200, US$500, or US$800, randomly determined for each separate trial. Each participant completed six separate trials, one for each of six time delay intervals (1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year). The choices were presented to the participant in the form of a verbal question (e.g. “Which would you prefer, $500 Today or $1000 in Six Months?”) and the participant, under no time constraint, proceeded to choose one of the two values. If the immediate reward was chosen, the next question in the trial presented an immediate reward midway between the prior immediate reward value and zero (i.e., a lower amount). If the delayed reward was chosen, the next question presented an immediate reward midway between the prior immediate reward and US$1000. This titrating pattern continued, with all subsequent questions presenting immediate values midway between the reward rejected and the previously rejected higher or lower reward, until participants’ choices converged on an indifference point (Ohmura, Takahashi, Kitamura, & Wehr, 2006) – the value subjectively equivalent to the discounted delayed reward if the value was offered immediately (Green, Myerson, & Macaux, 2005). The individual’s indifference points at each delay interval were calculated, subsequently averaged to determine the average indifference point, and further analyzed to determine each participant’s discount rate.

The discount rate (k) is an index of the degree to which an individual devalues delayed rewards as a function of the length of delay to receipt of the delayed reward (O’Brien et al., 2011; Ohmura et al., 2006). The standard equation used to compute this value is V=A/(1+kD), where V is the subjective value of the delayed reward (indifference point), A is the actual value of the delayed reward (in this case, always US$1000), D is the time delay interval, and k is the discount rate. Higher discount rates indicate increased devaluation of delayed rewards in favor of immediate rewards. The correlation between average indifference point and discount rate in the present sample was r = −.83, p<.001.

Results

Indifference Point

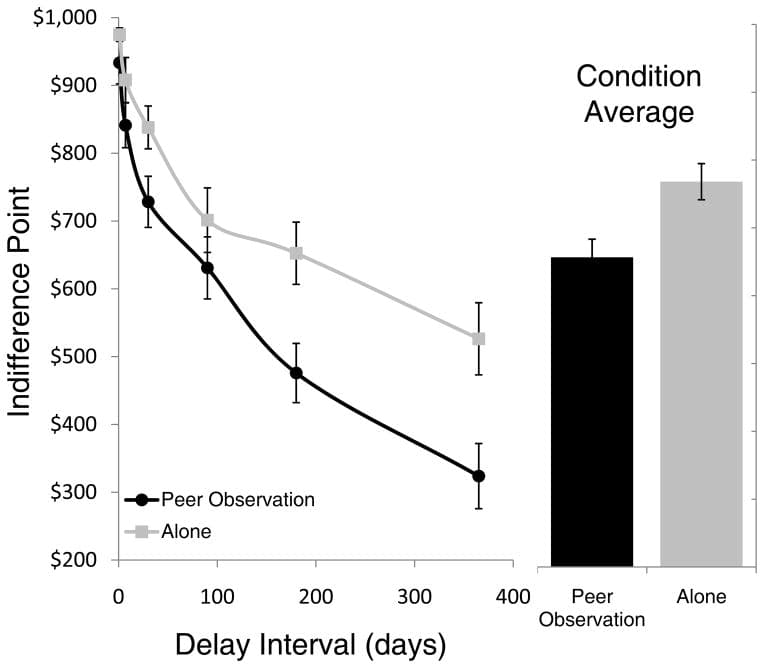

Indifference points were calculated for all six delay periods (1 day, 1 week, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year). A repeated-measures ANOVA was carried out on individuals’ indifference points using experimental condition (peer versus alone) as a between-subjects factor and the 6 delay intervals as a within-subjects factor. Consistent with prior research on delay discounting, there was a main effect of delay interval, F(5,310)=74.30, η2=.55, p<.001, such that participants opted for a smaller immediate amount as the interval increased. Consistent with our hypothesis that there would also be group differences in average indifference points, a significant main effect of experimental condition was found, F(1,62)=8.58, η2=.12, p<.01, such that participants in the peer condition evinced significantly lower indifference points (M=$656.68, SD=150.92) than those in the alone condition (M=$768.16, SD=150.76). This result, shown in Figure 1 (right), indicates that across time delay intervals participants who believed they were observed by an anonymous peer opted for smaller immediate rewards than those completing the task alone.

Figure 1: Average indifference points for each social condition. Shown on the left are the average indifference points, separated by time delay interval, for participants in each condition. Shown on the right are the condition means, collapsed across all time delay intervals. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. A marginally significant interaction was found between the delay interval and experimental condition, F(5,310)=1.998, η2=.03, p=.079, suggesting that the difference between the peer and alone conditions with respect to indifference points is larger at some delay intervals than others (See Fig. 1, left). To explore this possibility, group differences were assessed at each separate delay interval, using separate independent samples t-tests for each interval. Results of this analysis indicated that there were significant differences between groups only at delay intervals of one month, t(62)=−2.233, η2=.07, p<.05; six months, t(62)= −2.785, η2=.11, p<.01; and one year, t(62)= −2.823, η2=.11, p<.01.

Discount Rate (k)

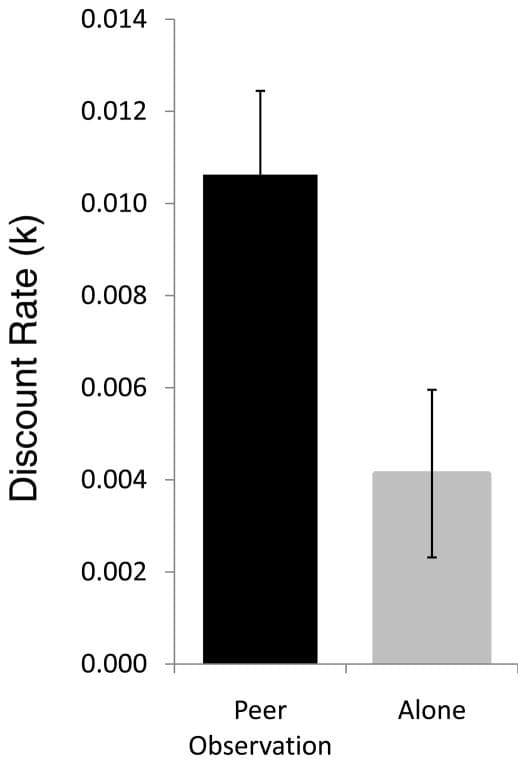

Each individual’s discount rate (k) was calculated according to the formula given above, and additional analyses were conducted to investigate whether the experimental manipulation also caused differences in discount rates. Consistent with the average indifference point findings, an independent samples t-test based on k value estimates revealed a highly significant main effect of experimental condition, t(62) = 3.05, η2=.13, p=.003, indicating that participants who believed they were being observed by a peer exhibited steeper discounting on average (k=.0136) than those who were not observed (k=.0053). As in our earlier investigation of discounting behavior in this age cohort (O’Brien et al., 2011), k values for the present sample were highly variable and exhibited a large degree of positive skew (7.68). Accordingly, and in order to confirm that outliers did not have an undue influence on the results, we computed z-scores for each individual’s k value and repeated the analysis while excluding subjects with z-scores greater than 2.5 (N=4). Comparisons conducted on the remaining subjects (N=60) again indicated a highly significant main effect of experimental condition, t(58)= 3.373, η2=.16, p=.001 (See Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Average discount rates (k) for individuals in each condition. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Discussion

The present results indicate that, in late adolescents, the knowledge that one is being observed by an anonymous person of like gender and age can increase sensitivity to immediate rewards. Consistent with prior research using actual friends (O’Brien et al., 2011), adolescents in the present study who believed that an anonymous peer was watching their performance evinced lower indifference points and steeper discount functions than those who performed the task alone. These findings lend support to the notion that the impact of peers on adolescent risk taking is, at least in part, due to an increase in reward sensitivity when aware of that one is being observed by age-mates.

The results are also informative with respect to the three specific questions we sought to answer in creating the current experimental paradigm. First, the results show that even peers whom adolescents do not know personally can elicit an increase in their preference for immediate rewards. Second, the fact that only one anonymous peer was thought to be observing participants’ behavior in the experimental condition suggests that the peer effect on reward sensitivity does not depend on the presence of multiple age-mates. Third, consistent with the suggestions of prior fMRI research that distant peer observation via a computer can cause increased activation of the reward system (e.g. Chein et al., 2011; Guyer et al., 2008), the present results show that the effect of peer observation on adolescents’ sensitivity to immediate rewards can occur when peers are not physically present, but simply observing behavior from afar. Further, because participants could not communicate freely with the observer, the peer effect on immediate reward sensitivity in this study can be attributed only to the participant’s belief that he or she is being observed by an age-mate, and not to any overt peer pressure. We remind the reader that although these findings indicate that none of these factors – personal familiarity with the observer, multiple observers, physically proximal observation – is a necessary precondition for obtaining a peer effect on delay discounting behavior, they do not provide any direct evidence for whether the magnitude of the effect is moderated by these factors.

A comparison of the present findings to those from a prior study of peer influences on delay discounting (O’Brien et al. 2011) does, however, provide at least preliminary evidence that the effect is not markedly sensitive to these factors. In the earlier study, delay discounting behavior was obtained while two known friends sat on either side of the participant, and the peers were able to communicate freely during the session. In the present study, participants believed that a single, unknown, individual was observing from another room, and interactions between the participant and “observer” were highly constrained. Despite these differences, the magnitude of the peer effect (expressed as a percentage of the alone average) is almost identical across the two studies – 85% in the present sample, and 89% in the O’Brien et al (2011) sample – and the condition effect size was actually larger in the present sample (Cohen’s d = .74) than in the O’Brien et al sample (Cohen’s d = .40). One potential caveat in comparing these two studies is that participants in O’Brien et al produced somewhat lower average indifference points ($675 alone, $604 peer) than did those in the current sample ($768 alone, $657 peer), perhaps owing to the slightly, but significantly, older age of the current group (M=19.3 years) relative to that of O’Brien et al (M=18.5 years); t(162) = 6.5, p <.01. Previous studies have indicated that the average indifference point evinced by individuals tested alone increases as a function of age (Steinberg et al., 2009).

In the current study we tried to limit the amount of interaction between participants and the peer observer to a bare minimum: a brief introduction and three innocuous confirmatory statements. Participants had no information about the observer that would lead them to guess what choices in the task would make them appear more socially acceptable. Therefore, the current paradigm provides an element of experimental control that did not exist in prior research, in which participants and their observers were close friends and could communicate freely. The fact that a similar pattern of results was observed suggests that the increase in reward sensitivity caused by the presence of peers is not due to conscious considerations of one’s friends’ values and attitudes. Questions about the peer effect among other age cohorts (e.g., younger adolescents, slightly older adults) and with observers who may not be considered by the participant as “peers” (e.g. an older observer, laboratory staff), might also be explored in future studies, with potentially important implications for efforts to mitigate peer influences and for the conduct of basic behavioral research.

The finding that an anonymous peer who is not physically present can affect adolescents’ reward preferences, and likely their risk taking, also has important implications for the safety of adolescents who use the Internet to communicate. Adolescents report spending close to 10 hours a week, on average, on the Internet (Subrahmanyam & Lin, 2007), and a variety of risk behaviors, such as revealing personal information online, can occur as a consequence of Internet use (Livingstone & Helsper, 2007; McCarty, Prawitz, Derscheid, & Montgomery, 2011). The results of the current study suggest that, while interacting with friends or even anonymous strangers over the Internet, adolescents’ risk taking may be increased to the same degree and through the same mechanism as when adolescents are actually with their friends.

One plausible alternative explanation for the pattern of results reported here is that awareness of an observer is simply distracting, leading to random or less contemplated responses from participants in the peer-observer group. If this were true, the findings might simply reflect a comparison between more (peer condition) and less (alone condition) distracted participants. However, the discount function seen in the responses of the participants who believed they were observed does not appear at all random, but, rather, follows the pattern of hyperbolic discounting obtained in a very large number of prior studies (see e.g. Teuscher & Mitchell, 2011). To further ensure that the results were not due to distraction, choice reversals, or instances in which participants’ indifference points for a given delay interval are higher than for shorter delay intervals (which would be “irrational” and likely due to inattention), were compared between the groups (details provided with supporting information available online). If participants in either group were relatively more distracted, they should show more such reversals. Although reversals did occur, there were no group differences, (t(62)=0.19, p=.85), indicating that the anonymous peer manipulation was not especially distracting.

As noted in the introduction, another possible limitation of the study is the fact that the present sample contained individuals who might categorically be referred to as either late adolescents or early adults. Risk-taking behaviors, sensation seeking, and impulsivity tend to peak somewhat earlier in adolescence (Steinberg, 2010), so the generalizability of the present findings to early adolescents remains unknown. We do know from prior studies, however, that early adolescents are more susceptible to the peer effect than college undergraduates (Chein et al., 2011; Gardner & Steinberg, 2005), so we have no reason to think that the present findings would not also apply to younger teenagers. Future studies can address this issue by implementing the same paradigm with early adolescent participants.

Conclusions

In sum, the present study provides essential clues regarding the origins of the impact of peers on adolescents’ decision-making. The results also address (and discount) several alternative explanations for the phenomenon, and validate a novel experimental paradigm for future research in the area. The experimental paradigm employed here can be easily adapted by changing the demographic profile of the anonymous observer and/or the content of the observer communication to explore new questions about the specificity of the peer effect. For instance, the paradigm also could be adapted for use in different populations, cultural contexts, and age groups, and to support research examining how the age, gender, values, or ethnicity of the peer observer moderates the peer effect on reward sensitivity or risk behavior.