Abstract

As drug-related offense and illicit drug overdose rates continue to grow in the United States, criminologists have begun to pay more attention to factors influencing illicit drug use as well as effective methods of promoting drug abstinence in treatment programs across the nation. Although much scholarly attention is given to community-based substance abuse treatment programs, a considerably smaller focus of research is devoted to substance abuse treatment programs that are prison-based. Moreover, some of the most effective methods of treating inmates who are addicted to an illicit drug (such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Therapeutic Community, etc.), although praised for their initiative and theoretical effectiveness, are often demonstrated via individualized empirical study that the expected advantages of such programmatic forms of treatment fail to emerge. The present study explores what scholars have discovered regarding the effectiveness of prison-based substance abuse treatment programs, how such findings appear to contradict one another, and why state prison systems should be more transparent regarding their in-house drug treatment programs in their publicly accessible reports that are formulated into cumulative reports on each states’ Bureau of Corrections websites.

Introduction

Never has there been a more crucial time for drug addiction and drug treatment program related research. As drug addictions and dependencies are steadily increasing globally (Saini et al., 2013) and overdose on illicit substances continues to grow (Jakubowski et al., 2018), there is an apparent need for greater conceptual understanding of how to combat the rise of illicit drug use and, perhaps more pressingly, what are the current measures being taken by the United States to treat such individuals. With the current rise in drug addiction and drug-related deaths, scholars have been giving the topic of drug use and drug addiction increasingly more attention, often describing drug addiction as a health problem (Priest et al., 2020) and a social issue (Weinberg, 2000). Although this attention is ultimately necessary and has increased the greater understanding of illicit drug-related issues, a need exists for greater attention to be offered pertaining to the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of substance abuse treatment programs. Furthermore, while many empirical studies exist that draw samples from community-based substance abuse treatment programs, relatively little attention is given to such programs that are prison-based. The reason for this disparity in attention is unclear; however, it should be stressed that scholarly study of programs that seek to treat those with illicit drug addiction should be equal among those who are sentenced to prison and those who are not. Moreover, in an era where rates of drug addiction, drug dependency, and drug-related deaths are greater than ever, it is vital that all programs that attempt to treat those with illicit drug addiction be observed and studied for their effectiveness, whether they house criminal offenders or law-abiding citizens.

The drug crisis is ramped among U.S correctional systems. Efforts to utilize substance abuse programs in the criminal justice system have long been practiced in the United States, however with highly inconsistent results. For juvenile drug offenders, Schwalbe et al. (2012) discovered that of those who were sent to juvenile detention facilities compared to those who were diverted and sent to individualized treatment centers, there was a noticeable, albeit slim, reduction in the likelihood of recidivism. Furthermore, regarding adult drug offenders, there is also a noticeable decrease in the likelihood of recidivating if sentenced to some type of substance abuse treatment facility or program rather than being incarcerated (Belenko et al., 2013). However, the likelihood of adults being diverted from jail or prison time and sentenced to a substance abuse treatment facility or program remains slim at best. Approximately 80% of those who are sentenced to jail or prison have used an illicit substance at least once in their lives or possess a diagnosable case of addiction, with over half of those incarcerated having used an illicit substance at least a few months prior to their conviction (Belenko & Peugh, 2005). Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, over half the population of inmates in U.S. prisons have DSM IV diagnosable addictions and dependencies for either methamphetamine, crack, cocaine, or heroin (Belenko & Peugh, 2005). Thus, with over half a million Americans incarcerated due to drug offenses, and the majority of those housed in jails and prisons possessing an addiction toward an illicit substance despite their offenses not necessarily involving a drug-related offense, there is an obvious need for greater attention toward the ability for prison-based substance abuse programs to effectively treat those with addictions and dependencies and how they are currently faring in rates of graduation versus rates of resignation or recidivism.

This paper addresses the current lack of knowledge pertaining to how prison-based substance abuse treatment programs operate as well as the reality that the overwhelming vast majority of such programs do not publicly disclose basic information pertaining to the programs’ bed counts, participant enrollment, participant attendance, participant resignation, participant recidivism, and participant graduation, and funding given to these prison-based programs. Research on this topic is both timely and imperative considering the social and health issue of illicit drug addiction in the United States and thus prison-based programs that seek to treat those with drug addiction should be significantly more transparent to the public regarding their effectiveness. The review of literature will then shift the focus toward what is currently known about prison-based substance abuse treatment programs regarding their successes and failures as well as how many findings from such studies appear to contradict one another. In continuation we call for increased attention toward prison-based programs that house an exceedingly large number of men and women requiring substance intervention services. The lack of publicly accessible data reported by state prisons regarding their in-house substance abuse treatment program will then be discussed. This paper will conclude with suggestions for future research avenues for criminal justice scholars as well as recommendations for state prisons and their analysts to begin publicly reporting information about their programs and their effectiveness to create greater transparency and addiction that is accountability for correctional systems and their steps toward minimizing illicit drug.

Prevalence of Drug Addiction in U.S. Prisons

Approximately 80% of those who are sentenced to prison have used an illicit substance at least once in their lives or possess some type of substance addiction, with over half of those incarcerated having used an illicit substance at least a few months prior to their conviction (Belenko & Peugh, 2005). Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, over half the population of inmates in U.S. jails or prisons have DSM-IV diagnosable addictions and dependencies for either methamphetamine, crack, cocaine, or heroin (Belenko & Peugh, 2005). While evolving policy to better to address the over-punishment of drug possession crimes is indeed a step in the right direction for decreasing the mass incarceration of drug offenders, it does not however truly get to the root of the problem. The issue is not simply to decrease the severity of sentences for those convicted of drug possession, but rather creating the means to which those who possess addictions toward illicit drugs can find adequate treatment. Therefore, while some states may attempt to decrease the amount of drug offenders who are incarcerated each year (Cole, 2011), this does not address the large portion of inmates who possess DSM-IV diagnosable cases of drug addiction who were not initially charged with drug possession. Moreover, if over two million people are incarcerated in jails or prisons in the United States on any given day (Cole, 2011), and over half of these inmates possess DSM diagnosable cases of drug addiction of dependency (Belenko & Peugh, 2005), then we can safely estimate that over one million American inmates are in need of substance abuse treatment. However, according to Sawyer and Wagner (2019), there are a little over half a million inmates that are incarcerated due to involvement in drug crimes. Therefore, there is an additional estimated half a million American inmates that are currently incarcerated with some level of drug addiction or dependency but were not incarcerated due to being charged with a drug crime.

It can be assumed that many of those who are incarcerated for various crimes were under the influence of illicit drugs during the time of committing the offense, as drugs would undoubtedly decrease one’s sensibility and make certain decisions seem rational that would otherwise be irrational. According to Mumola and Karberg (2007), approximately 32% of those incarcerated in state prisons admitted to being under the influence of drugs at the time of engaging in their offense. This demonstrates that one in every three prison inmates possessed a compromised ability to rationally decide their actions, meaning that criminal involvement is often the result of one being under the influence of drugs but does not explain all criminal behavior nor involvement in all drug crimes. However, what does add to this body of knowledge is Mumola and Karberg’s (2007) additional finding that approximately 16.5% of state prison inmates reported their decision to commit their crime was in order to obtain money for purchasing more drugs. This finding shows that being under the influence of drugs at the time of offense is not necessarily the only instance in which drugs may influence one to engage in crime. Rather, people who feel the need to use more drugs, a feeling most characterizable as a drug dependency or addiction, will shed their rational beliefs of resisting involvement in criminal behavior in an effort to obtain what they deem to be more important than following the law and social norms. Additionally, because of ineffective treatment methods for drug addictions and dependencies combined with inadequate availability of substance abuse treatment for drug offenders, 68% of offenders who are deemed “drug-involved” will recidivate within 3 years prior to being released from jail or prison (Langan & Levin, 2002). Thus, there is an understandable need for the United States to properly address the high number of drug-involved offenders incarcerated in jails and prisons rather than relying on ineffective means of incarceration that more than likely lead to recidivsim. With an understanding that illicit drug use increases one’s likelihood of continued engagement in criminal behavior (Langan & Levin, 2002), a foreseeably effective method to countering crime persistence is to create more opportunities for treatment while housed in prison.

Prison-Based Substance Abuse Treatment Programs

Although the vast majority of evaluative research that has sought to understand the effectiveness of prison-based substance abuse treatment programs were conducted well over a decade ago, the general consensus is that such programs have demonstrated moderate to significant success in promoting both drug abstinence and a reduced likelihood of recidivism (Bahr et al., 2012; Melnick et al., 2004; Prendergast, 2003). Residential programs offer those who are incarcerated in prisons assistance in managing their substance dependencies and addictions through a variety of methods. Such programs include cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), contingency management, therapeutic communities, pharmacological treatment, boot camps, and twelve-step programs (Bahr et al., 2012). However, each of these methods of treating substance dependency and addiction differs drastically, and therefore each type of program will be discussed in more detail regarding its procedures, objectives, and empirically demonstrated effectiveness.

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) approaches the topic of addiction as an issue with one’s mindset. More specifically, it assumes that in order to cure or address addiction, treatment must involve processes of shifting individuals’ attitudes and beliefs toward bettering their interpersonal skills (Milkman & Wanberg, 2007). This often involves the creation of activities or work assignments to promote prisoner involvement and development of such skills (Lowenkamp et al., 2009). In an analysis of two prison-based CBT programs, Pelissier et al. (2001) found that prisoners who completed a 6-month long CBT program were significantly less likely to use illicit substances or be rearrested within 6 months of release. In addition, other evaluative studies that have sought to uncover the effectiveness of CBT in treating substance dependence and addiction have shown CBT to be an effective, albeit short term, method of promoting drug abstinence while decreasing the likelihood of recidivism (Easton et al., 2007; Kadden et al., 2007; Rawson et al., 2006). Therefore, it can be assumed that CBT is indeed a viable method of treating those incarcerated in prison systems and may perhaps demonstrate further effectiveness when paired with other means of treatment.

Contingency Management

Contingency management involves the idea that good behavior can be facilitated through the introduction of rewards. in regard to drug treatment, participants who perform favorably, whether it be via negative urine samples, regular attendance, etc., will receive prizes in order to reinforce positive behavior (Bahr et al., 2012). Evaluative studies have demonstrated that contingency management treatment programs can significantly increase drug abstinence for its participants who possessed dependencies toward marijuana (Budney et al., 2006; Kadden et al., 2007), methamphetamine (Rawson et al., 2006; Roll et al., 2006), cocaine (Epstein et al., 2009; Olmstead & Petry, 2009), and opiates (Epstein et al., 2009; Olmstead & Petry, 2009). Although contingency management shows similar levels of success as CBT (Rawson et al., 2006), Dutra et al. (2008) found that when contingency management and CBT are combined into a single program, greater results are produced. However, there is a lack of attention toward the overall effectiveness of contingency management program’s long-term effects, meaning that once participants are no longer awarded prizes or vouchers for their good behavior, they are significantly more likely to discontinue their drug abstinence (Bahr et al., 2012).

Therapeutic Communities

Therapeutic community programs are unique in that they provide more power toward their participants. Participants are organized into groups that then possess their own means of governance and responsibility (Bahr et al., 2012). The reasoning behind this structure is that since the responsibility of participants is toward other members of their community, it creates peer pressure to conform to the demands of the program while also creating greater attention toward accountability (De Leon, 2000). Sherman et al. (2002) as well as Seiter and Kadela (2003) evaluated the practicality and effectiveness of utilizing therapeutic community programs within prisons in California, Delaware, and Texas and found that those who were involved in such programs exhibited greater rates of drug abstinence compared to prisoners who were not involved in therapeutic community programs. Additionally, those who completed therapeutic community programs in Pennsylvania showed lower rates of recidivism upon release compared to those who did not participate in such programs (Welsh, 2007). Therapeutic community programs can also be modified to better suit the needs of their participants, such as the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ Residential Drug Addiction Programs (RDAP) which houses prisoners in a prosocial environment filled with work and school activities. RDAPs have demonstrated significant success in in reducing recidivism for its graduates as well as gradates being far less likely to relapse.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological treatment methods have made tremendous improvements regarding substance addiction within the past few decades. There are two categories of drugs that are used to treat substance addiction, the first being agonists. Agonists are drugs that are used to act as replacements for more harmful substances, such as using methadone to treat those who are addicted to heroin (Bahr et al., 2012). The other category of drug used to treat substance addiction are antagonists, which are drugs used to neutralize illicit drug effects and to reduce cravings (O’Brien, 1997). In addition to the treatment of heroin, pharmacological treatment programs have also demonstrated their effectiveness regarding those who are dependent upon or addicted to alcohol via Topiramate (Baltieri et al., 2008), opiates via Buprenorphine (Marsch et al., 2005), and cocaine via Naltrexone (Bahr et al., 2012), although Naltrexone as well as many other pharmacological treatment medications have shown mixed results. In summary, pharmacological treatment has demonstrated promising results regarding its effectiveness in treating substance dependence or addiction, especially when it is combined with other forms of treatment such as CBT (Bahr et al., 2012).

Twelve-Step Programs

Twelve-step programs are perhaps the most nationally recognized forms of treating substance dependence and addiction. Popular examples of twelve-step programs include Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, and Cocaine Anonymous (Bahr et al., 2012), that have been operating for decades. These programs are based on the idea that addiction is a life-long problem that is able to be controlled; however, it may never truly be cured. Moreover, the major components that make up twelve-step programs is to first make participants more aware of their addiction and gain a greater understanding of it, followed by weekly or biweekly meetings, learning to perform services to others, and attending counseling sessions with professionals (Schneider, 2006). Although twelve-step programs are widely used, research has shown that such programs do very little to reduce recidivism and drug relapse (Babor & Del Boca, 2003; Zanis et al., 2003). Thus, although twelve-step programs may not be as effective as other means of treatment, such as CBT or therapeutic communities, it may however demonstrate greater success if combined with other such programs.

Prison-Based Substance Abuse Treatment Program Shortcomings

Although prison-based substance abuse treatment programs have been shown via empirical study to contain benefits for reducing recidivism by promoting drug abstinence, they are not however without their faults or shortcomings. Understanding that over 50% of state prisoners meet the DSM-IV criteria for drug addiction, it would be expected that state prisons would then be more likely to focus a great deal of attention toward the treatment of their inmates to reduce recidivism (Welsh et al., 2014). However, less than half of all inmates that are determined to be drug-dependent report ever taking part in a treatment program, with a staggering one in five of these inmates having met with trained professionals for counseling, drug education, or treatment (Welsh et al., 2014). It is apparent that state prison systems fall short regarding providing necessary access and participation in substance abuse treatment programs. Only a third of inmates who possess histories of substance abuse report ever taking part in a treatment program at any point during their sentence (Belenko & Peugh, 2005), meaning that the U.S. correctional system is not currently meeting the demand for treatment program access that is required among its inmates.

Although some studies have demonstrated CBT as an effective means of creating drug abstinence among state prisoners, there are also studies that present no such association exists. Strah et al., 2018 concluded via a propensity score matching method that graduation from a CBT program did not yield a significant decrease in alcohol or drug misconduct compared to prisoners who did not graduate from a CBT program. In a study of Contingency Management, another method of treating drug-dependence in prisons, Hall et al. (2009) found that once participants were discontinued from receiving rewards for their drug abstinence, their continued abstinence would significantly decrease soon after. Additionally, drug offenders who are not considered “high-risk” who participate in Therapeutic Communities show similar rates of recidivism as those who did not participate. Twelve-step programs are another method of treating prisoners with drug dependencies that is among the oldest types of treatment programs. However, although this method of treatment has been used for decades, it has demonstrated little empirical evidence regarding its effectiveness (Bahr et al., 2012). Moreover, the issue remains that prison-based substance abuse treatment programs remain a somewhat unaccounted for area of literature, and thus even findings that point to promising results are still yet to be truly generalizable (Strah et al., 2018). This issue is intensified when one considers that sociological research studies that report null findings, particularly those that contain programmatic evaluation, are rarely ever approved for publication (Gerber & Malhotra, 2008). Therefore, in addition to there being much we do not know about prison-based substance abuse programs and their effectiveness, it is reasonable to assume that some studies that may have contributed to our understanding of how such programs operate and potentially contribute to reductions in recidivism may have gone unpublished. It should be noted that studies that produce negative or null findings are also important as it assists in establishing an argument for “what works” regarding correctional system programming (Pratt, 2002). However, the reality remains that a publishing bias exists, and thus it is more difficult to establish an argument for what treatment programs work and which are simply ineffective. Furthermore, with such a vast variety of empirical studies that demonstrate how such programs can be both effective and ineffective, the question remains these programs are simply not being utilized to their fullest potential or are in need of crucial reconstruction.

Methods

To explore the effectiveness and practicality of prison-based substance abuse treatment programs, we rely on data collected from each state’s Bureau of Corrections via annual, semi-annual, monthly, weekly, or daily prison reports. Data collection began in November of 2021 and lasted until April of 2022. The method of data collection involved the primary researcher visiting each state’s Bureau of Corrections webpage and compiling information within annual, semi-annual, monthly, weekly, or daily reports that pertained to prison population, drug arrests, how often reports were created, drug offenders in custody, number of inmates who possessed a substance abuse history, number of drug treatment programs, presence of women-only programs, number of beds filled or empty, number of inmates enrolled in residential substance abuse treatment programs (RSAT), RSAT completions or rate of completion, RSAT average attendance, RSAT state funding, money spent on RSAT programs, and RSAT federal funding in December of 2019. December of 2019 was specifically chosen as the date of data collection as many states did not report prison data for the years of 2020 and 2021 at the time of data collection. Additionally, annual reports appeared to place a greater emphasis on the end of the annual year, which matched other states’ methods of monthly reporting. Thus, December of 2019 was the most consistent point in time of prison data reporting and therefore the most suitable for data collection.

Data collected from each state’s Bureau of Corrections differed drastically, with many states not including basic information such as their population of drug offenders, population of substance abuse treatment program enrollees, or even maximum occupancy for such programs. Due to the high variability of state prison reports, we chose to record all information that pertained to prison population, drug arrests, how often reports were created, drug offenders in custody, number of inmates who possessed substance abuse history, number of drug treatment programs, presence of women-only programs, number of beds, inmates enrolled in residential substance abuse treatment programs (RSAT), RSAT completions or rate of completion, RSAT average attendance, RSAT state funding, money spent on RSAT programs, and RSAT federal funding in December of 2019. This issue is likely due to the understanding that each state’s prison system is designed independently of one another, meaning that it is perceivable why the methods of reporting prison data, such as population changes and other statistics, differed state by state. However, the data that were present in reports that we collected, or perhaps more importantly lack thereof, is still significant in that it demonstrated a possible substantial shortcoming for the U.S. correctional system. Moreover, if state prison population reports continue to remain individualized and lacking a universal method of statistical coverage, it will likely continue to remain challenging for scholars to cross-examine the effectiveness and practicality of prison-based programs state-by-state.

For this paper, the data that were collected will be cross-examined state-by-state in order to uncover findings related to population of inmates, population of drug offenders, RSAT programs available, number of beds, RSAT participation, RSAT graduations or rate of graduation, state funding for RSAT programs, federal funding for RSAT programs, and state expenditures for RSAT programs. Partial data have been collected from 39 of the 50 states, although data on drug related arrests as well as prison populations as of December 2019 have been collected for all 50 states from the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) Uniform Crime Report (UCR) and The Sentencing Project’s state-by-state data on prison population by month/year. Statistics from the remaining 20 states were not included in this analysis as their Bureau of Corrections prison reports did not include data pertaining our previously mentioned data collection. After collected data were cross-examined, this paper presents the greatly varying methods of prison data reporting state-by-state while also demonstrating the effectiveness and practicality of current prison-based substance abuse treatment programs according to the data that has been provided in the reports.

What We Can Obtain From Prison Reports

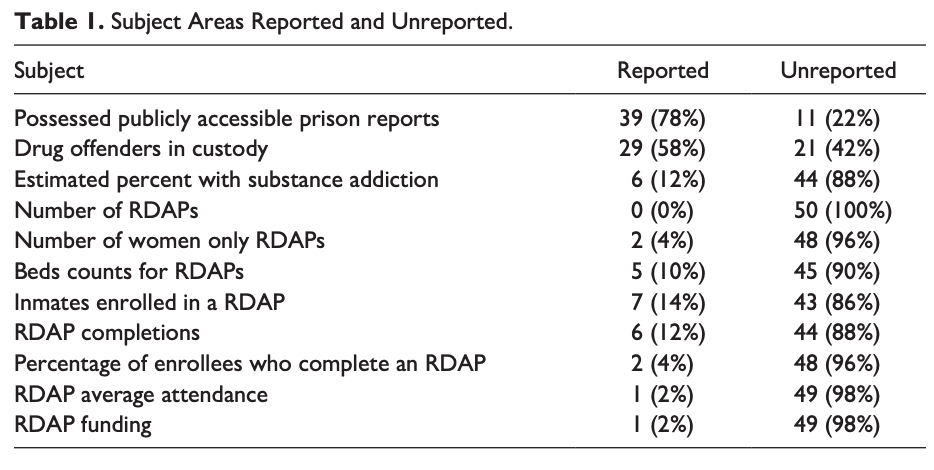

Once data were collected from each of the 50 U.S. states, only partial data were obtained from 39 states, with the remaining eleven states’ Bureau of Corrections websites not including publicly accessible prison reports that allowed us to run our analyzes. According to data obtained outside of state prison reports, we learn that the average prison population housed in state prisons as of 2019 was 24,439 (Sentencing Project), with the average number of drug arrests occurring in each state as of 2019 being 23,838 (UCR), although this statistic is likely to be highly questionable due to issues regarding the UCR’s methods of data collection. However, according to the 39 states that possessed publicly accessible prison reports, these findings should also be noted to possess many limitations and issues. First, it is worth noting that although eleven states did not present prison reports from 2019, many of these states did include some range of prison statistics, ranging from seemingly random yearly gaps in research to some states only reporting data up to a certain year, such as Maine which appeared to have only included prison population reports up until the year of 2010. This appears to be an act of neglect that should no longer be ignored. For the sake of this missing data in creating both a lack of accountability for state prisons as well as producing additionally obstacles for scholars to conduct research, this level of disregard for reporting techniques and regulations may be highly detrimental. Additionally, while 39 states did include some sort of population or other statistical report for their prisons, much of the data were both limited and scattered which shall be discussed. Table 1 presents a simple matrix that includes the number of states that included the information we were observing for as well as the number of states that did not include any mention of such topics in their state prison reports as of December 2019.

Table 1. Subject Areas Reported and Unreported.

The first variable that we coded was any mention of a definitive measure pertaining to how many drug offenders were in custody as of the end of the fiscal year of 2019. Twenty-nine out of the 39 state reports mentioned any notes on their population of drug offenders or those who were incarcerated because of some sort of drug related offense. The average population of drug offenders incarcerated in state prison facilities according to these reports was approximately 3,129 as of December 2019; however, this finding is quite low and is likely skewed as only slightly more than half of U.S. states recorded this measure. We also observed for any mention of estimated inmate population with drug addiction/dependency. We found that only six states, Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Indiana, Missouri, and Pennsylvania, included any comment within reports pertaining to an estimated percentage of prisoners in their state prisons that may possess some diagnosable level of substance addiction or dependency. Estimations ranged from 29% to 91%, with an average of approximately 67% experiencing some level of addiction or dependency. Next, we looked for mention of number of drug treatment programs that are made available for prisoners. However, we were not able to obtain any statistics from any of the state reports pertaining to such a topic. Number of women only drug treatment facilities were recorded next, with only two states, Alabama and Mississippi mentioning such facilities, with Alabama noted that two such facilities existed and Mississippi mentioning a single facility. Continuing our analyzes, we wanted to note the total number of beds reserved for in-house substance abuse treatment programs within state reports. We found that only five states included such a measure, Arkansas, California, Florida, Kentucky, and Mississippi. Bed counts for RDAPs ranged from 298 in Kentucky to 9,099 in Florida, with an average bed count for RDAPs being approximately 2,795.

The next few measures are perhaps the most important in that they directly relate to RDAPs successes and shortcomings according to state prison population reports. First, we wanted to record the number of inmates who were currently enrolled in an RDAP as of December 2019. We found that only seven states, California, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, and Nebraska, mentioned any reference to their population of inmates receiving in-house substance abuse treatment. Inmate population of participation ranged from 81 in Delaware, to 5,303 in California and 5,323 in Georgia, with an average of approximately 2,249. Furthermore, we not only wanted to know how many inmates were enrolled in RDAPs according to these reports, but also completions, completion rates, and average attendance of such programs by inmates once enrolled. Regarding completions, only six states reported the total number of RDAP completion for 2019, being Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Mexico, and West Virginia. Values ranged from 124 completions in Mississippi prisons to 2,683 completions in Georgia prisons, with an average of approximately 728 completions across these six states. Furthermore, only two states recording a measure of inmate RDAP completions in the form of percentages, being California and Wyoming. Lastly pertaining to RDAPs, we observed for any mention of inmate attendance in these programs, in which all that could be found was a single measure from Alabama’s prison report stating that their average monthly attendance for RDAPs was 216 in 2019, with this measure meaning very little as it was unknown what the total population of inmates convicted of drug offenses currently were in 2019. The final piece of information coded was funding for in-house substance abuse treatment programs. Only one state reported any mention of this variable, with Alabama reporting to have contributed $673,189 toward RDAPs. The remaining 49 state prison reports we found to not include any mention of funding toward RDAPs or any other type of program dealing with substance abuse.

Call for Research and Accountability

Much of the research that has been conducted pertaining to whether or not substance abuse treatment programs are effective in reducing recidivism and promoting drug abstinence for its participants are performed using small-scale individualized programs. Moreover, the findings from such studies have yielded somewhat inconclusive results as although the slight majority of substance abuse treatment program studies may demonstrate favorable results for the use of these programs, many on the contrary demonstrate null effects regarding the practicality of such programs. Whether current findings promote consensus that substance abuse programs can be successful or not, it is unclear if the prevalence of such studies demonstrating favorable findings toward the use of such programs are the result of publishing bias of predictive findings rather than null findings. Furthermore, while an extensive body of research that regularly contradicts itself regarding the effectiveness of these programs, an additional issue remains. It is whether these programs are community-based or prison-based. It has been established through previous empirical scholarship that community-based substance abuse treatment programs are regularly found to be more effective at reducing recidivism and promoting drug abstinence for longer periods of time compared to those that are housed inside prison facilities. With such preexisting barriers to substance abuse based programmatic research, there currently exists a crucial need for some sort of centralized method of comparing prison-based substance abuse treatment programs across the nation. Seeing as how such programmatic research has yielded contradictory results thus far, we suggest that state prison systems become more accountable regarding their prison population reports that presently include simple statistics that are unusable for proper state-by-state analysis to uncover and promote a more centralized method of treating state prison inmates that possess DSM diagnosable cases of drug addiction and/or drug dependency that encompasses the highest rates of effectiveness.

In order to successfully produce and promote an effective centralized method of drug treatment for prison-based inmates, we call upon other scholars with interests in Criminal Justice-based issues and shortcomings to conduct more research focusing on both state prison reports demonstrating such vastly differing pieces of data as well as their in-house substance abuse treatment programs reporting limited findings. Although programmatic research is often difficult to manage and conduct, this issue is significantly amplified when one considers the incredible differences regarding the methods of operation within these prison-based substance abuse treatment programs. Such issues that have currently gone unexplored make an empirically proven successful centralized prison-based substance-based treatment program impossible. We also theorize that state political ideology may also influence the lack of data being reported, as there may be political motives as to why states do not currently report on some of the issues, and are not likely to do so in the future. State budgets may not be equipped to tackle the current lack of emphasis on promoting or maintaining RDAPs and thus data regarding the successes or failures of such programs are not being stressed by state leadership. The immeasurable differences among prison reports state-by-state create significant detrimental effects regarding comparative and programmatic research, and these differences are visible in state prison reports that were previously discussed. Questions raised by these issues include:

What states include higher rates of prison-based substance abuse treatment graduation/success?

What are the methods in which substance abuse treatment are being emphasized by each state?

What is the amount that each state is funding their in-house substance abuse treatment programs relative to their population of drug offenders and their number of graduations/successes?

What are the number of beds reserved for inmates enrolled in in-house substance abuse treatment programs relative to their population of drug offenders for each state?

Does the majority political ideology of a state influence its funding and implantation of prison-based substance abuse treatment programs for its inmates?

Further studies that seek to expose the issues within the methods of reporting prison statistics as well as a lack of emphasis on reporting data related to their in-house substance abuse treatment programs will allow us to more effectively interpret state prison data to better come to a conclusive consensus regarding what methods of treating drug offenders housed in state prison systems to be most effective. One way this can be done is by future scholarship to be conducted using state-by-state prison statistics as we have in this current study but only if state prison statisticians work to include more measures in their prison reports, such as the number of drug offenders, number of inmates who possess a drug addiction, RDAP enrolment, and RDAP graduation. Although more measures should be taken to increase the accountability of state prison systems, these measures are an effective first step in facilitating further study into the effectiveness of RDAPs using a method state-by-state analysis.

Conclusion

Considering the vastly differing methods of data presentation and inclusion in state prison reports across all 50 states, it is questionable whether state-by-state analysis, though practical in theory, could ever yield conclusive results. We suggest that continued use of current techniques of reporting state prison statistics is to fuel both the continuance of ineffective and unusable measures of state prison data as well as a lack of accountability by practitioners we operate such state prison systems. Thus, in order to promote more effective methods of running state prison systems, particularly their in-house programs for inmates with substance addictions and their methods of reporting prison population data, we postulate that states may benefit from increased collaboration with other states to both create a more unified method of reporting prison statistics as well as the promotion of more effective techniques of treating inmates who possess a substance addiction. Although state prison systems may conduct more detailed prison reports for the federal government that are not open to the public, we suggest that such reports be publicly available for both ease of data collection for scholars interested in conducting programmatic research and also to promote accountability for state prison systems that have yet to publicly disclose their funding toward in-house prison programs, RDAP enrollment, and RDAP success rates.