Abstract

The context in which drinking occurs is a critical but relatively understudied factor in alcohol use disorder (AUD) etiology. In this article, I offer a social-contextual framework for examining AUD risk by reviewing studies on the unique antecedents and deleterious consequences of social compared with solitary alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Specifically, I provide evidence of distinct emotion regulatory functions across settings, in which social drinking is linked to enhancing positive emotions and social experiences, and solitary drinking is linked to coping with negative emotions. I end by considering the conceptual, methodological, and clinical implications of this social-contextual account of AUD risk.

Alcohol is consumed by 70% of people 18 years and older in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2018). Although most U.S. adults do not experience problems related to their alcohol use, 5.8% have an alcohol use disorder (AUD; SAMHSA, 2018), defined as a “problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress” in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 490). Excessive alcohol use is a public health crisis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

One of the most challenging problems facing alcohol researchers is understanding why some individuals develop AUD. Major theories on the etiology (i.e., causes) of AUD have focused on intrapersonal (e.g., personality traits) and interpersonal (e.g., peer influence) factors that contribute to the development of pathological alcohol use (Sher, Grekin, & Williams, 2005). This review focuses on a critical but relatively understudied interpersonal factor in alcoholism etiology—the importance of considering whether alcohol consumption occurs in social or solitary settings.

Most adolescents and young adults who drink alcohol only do so in social settings (Creswell et al., 2012; Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014; Sayette, Fairbairn, & Creswell, 2016), with three quarters citing “to have a good time with friends” as the primary motive for their alcohol use (O’Malley, Johnston, & Bachman, 1998, p. 91). A substantial minority, however, also consume alcohol while alone, with about 14% of adolescents (Mason, Stevens, & Fleming, 2020) and 15% to 24% of young adults (Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020a) reporting that they at times engage in solitary drinking (most commonly defined as drinking while no else is physically present). Consideration of the context in which drinking occurs has important implications for understanding risk processes for the development of AUD (Creswell, Chung, Clark, & Martin, 2014; Sayette et al., 2016).

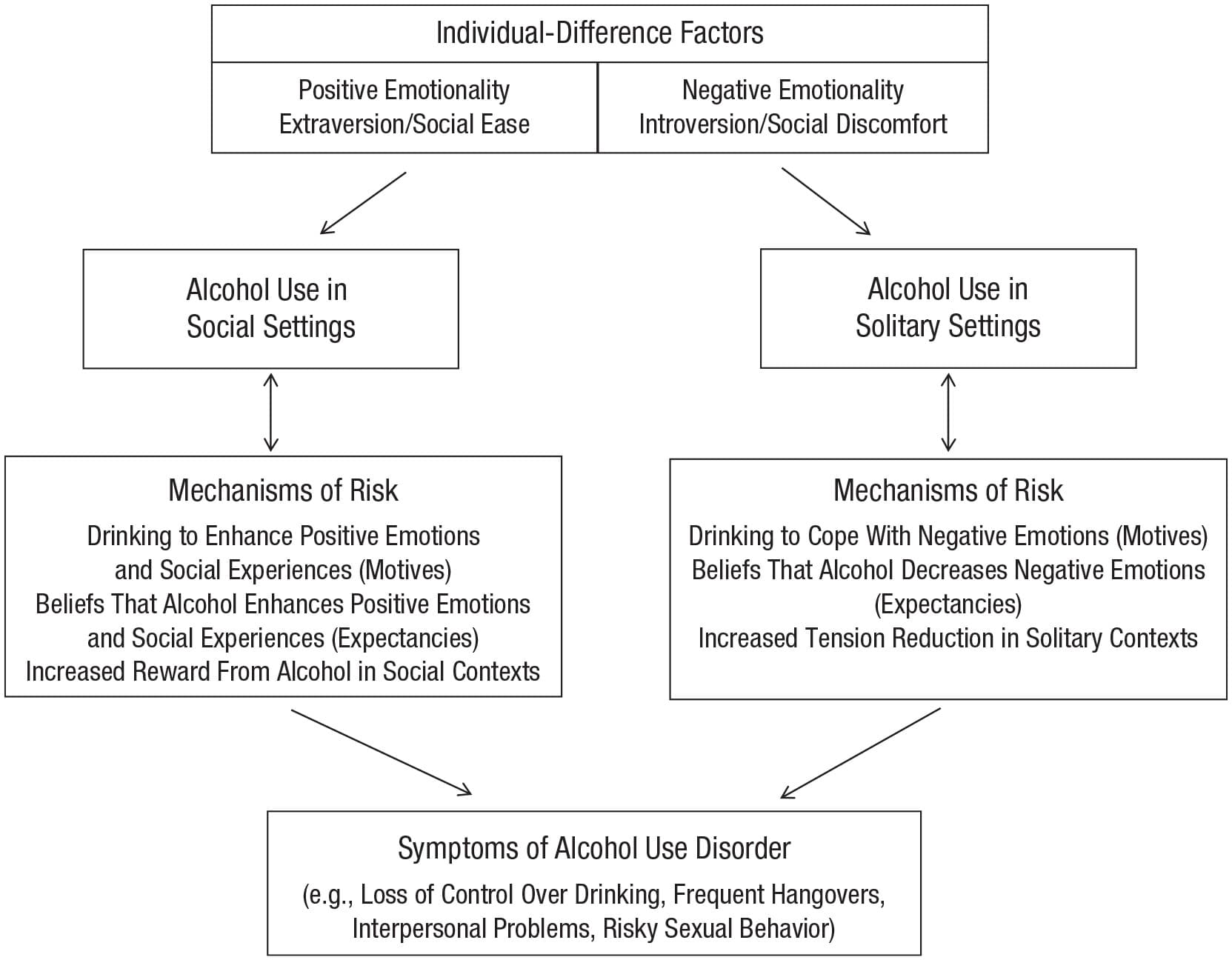

Here, I offer a social-contextual framework for examining AUD risk by highlighting the unique antecedents and deleterious consequences of social compared with solitary alcohol use (see Fig. 1). Specifically, I (a) review studies linking unique individual-difference factors to alcohol use across social and solitary settings, (b) provide evidence that drinking in both settings can be associated with heavy alcohol use and alcohol-related problems, (c) suggest that distinct mechanisms of risk for alcohol problems are associated with use in each setting, and (d) end with some broader considerations. I focus on adolescents and young adults because the vast majority of the research in this area has been conducted on these individuals.

Fig. 1. Social-contextual framework of risk for alcohol use disorder, illustrating how unique individual-difference factors are linked to alcohol use in social and solitary settings and how distinct mechanisms of risk for alcohol problems are associated with use in each setting. Arrows represent directional relationships between variables.

Unique Individual-Difference Factors

A growing literature has documented individual-difference factors that influence who goes into one of two directions—either restricting alcohol use to social settings or developing patterns of drinking alone. Among adolescents and young adults, drinking alcohol in social settings has been linked to positive emotionality and sociality (e.g., Cooper, Kuntsche, Levitt, Barber, & Wolf, 2016; Engels, Knibbe, & Drop, 1999). In contrast, adolescents and young adults who engage in solitary drinking report more negative affect and more social discomfort than their social-only drinking peers (see Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020a, for a meta-analysis). For example, adolescent solitary drinkers, compared with social-only drinkers, have higher levels of trait negative emotionality (Creswell, Chung, Wright, et al., 2015) and depressive symptoms (Tomlinson & Brown, 2012). Similarly, solitary drinking in young adults is associated with depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and lower distress tolerance (e.g., Gonzalez, Collins, & Bradizza, 2009; Keough, O’Connor, Sherry, & Stewart, 2015; Williams, Vik, & Wong, 2015), and a recent longitudinal study demonstrated that negative affect prospectively predicted young adult solitary drinking 4 months later, even after analyses accounted for baseline solitary drinking (Bilevicius, Single, Rapinda, Bristow, & Keough, 2018). Further, solitary drinking in adolescents and young adults has been linked to measures of social discomfort, such as social anxiety (Skrzynski, Creswell, Bachrach, & Chung, 2018) and loneliness (Gonzalez & Skewes, 2013). In sum, there appear to be unique individual-difference factors that are associated with alcohol use in social and solitary settings; social drinking seems to be related to positive emotionality and sociality, whereas solitary drinking seems to be related to negative emotionality and social discomfort.

Increased Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol Problems

Drinking in both social and solitary settings has been linked to heavy alcohol consumption and problems. Individuals often drink more alcohol in social settings than they do while alone (Monk, Qureshi, & Heim, 2020), and per-person alcohol consumption increases in larger (compared with smaller) social groups (Smit, Groefsema, Luijten, Engels, & Kuntsche, 2015), especially when socially normative information about heavy alcohol consumption is conveyed (Cullum, O’Grady, Armeli, & Tennen, 2012). This increased alcohol consumption in social groups is not completely explained by social modeling (Kuendig & Kuntsche, 2012) but is also attributable to characteristics of the drinking individuals (e.g., anticipated social facilitation; Smith, Goldman, Greenbaum, & Christiansen, 1995) and features of the social context (e.g., level of familiarity of group members; Fairbairn et al., 2018). Further, drinking in social settings is associated with negative alcohol-related outcomes that are likely markers of AUD, such as driving while intoxicated, alcohol-induced violence, sexual assault, and risky sexual behavior (Bersamin, Paschall, Saltz, & Zamboanga, 2012; Cleveland, Testa, & Hone, 2019; Mair, Lipperman-Kreda, Gruenewald, Bersamin, & Grube, 2015).

Solitary drinking has also been linked to increased alcohol use and problems (see Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020a, for a meta-analysis). Adolescent and young adult solitary drinkers report significantly greater alcohol use than their social-only drinking peers (e.g., Creswell, Chung, Wright, et al., 2015; Skrzynski et al., 2018). Importantly, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that any drinking while alone in adolescence prospectively predicts the development of alcohol problems over and above other baseline risk factors. For instance, Creswell and colleagues (2014) demonstrated that solitary drinkers between the ages of 12 and 18 years subsequently met more criteria for AUD symptoms at age 25 than did their social-only drinking peers, even after analyses controlled for adolescent alcohol use and problems. Similarly, Tucker, Ellickson, Collins, and Klein (2006) found that eighth-grade solitary drinkers, compared with social-only drinkers, went on to experience more alcohol problems at age 23, even after analyses accounted for eighth-grade alcohol use. What is noteworthy is that adolescent and young adult solitary drinkers still spend the majority of their time drinking in social settings (Creswell, Chung, Wright, et al., 2015; Skrzynski et al., 2018), yet engaging in occasional (typically ~25% of the time) solitary drinking is associated with increased alcohol use and the development of alcohol problems compared with their social-only drinking peers. Taken together, these findings indicate that alcohol use in both social and solitary settings is linked to heavy alcohol use and negative alcohol-related consequences. Importantly, the mechanisms of risk across these settings appear to be distinct.

Distinct Mechanisms of Risk

Adolescents and young adults report drinking in social settings to enhance positive emotions and social experiences (e.g., Cooper et al., 2016). Further, the belief that alcohol improves mood and social experiences is associated with problematic drinking (Leigh & Stacy, 1993) and, in prospective studies, is predictive of subsequent alcohol use and AUD symptoms years later (Patrick, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Johnston, & Bachman, 2011; Smith et al., 1995). Individuals who are highly sensitive to these emotional and social rewards of alcohol are thought to be at particular risk for developing alcohol problems (Grekin, Sher, & Wood, 2006). Accordingly, individuals who experience greater mood enhancement from alcohol in the laboratory have been shown to escalate their drinking over a 2-year period and develop AUD symptoms (King, de Wit, McNamara, & Cao, 2011).

Individual-difference factors that are associated with drinking in social settings (e.g., extraversion; Cooper et al., 2016) might also predict who obtains the most reward from alcohol in these contexts, placing them at greater risk to escalate their drinking. Sayette and colleagues (2012) conducted the largest study to date to evaluate alcohol’s social and emotional rewards in a laboratory social setting and to identify who is most sensitive to these effects. Healthy young adult drinkers (n = 720) were assembled into three-person groups of strangers and interacted with each other while consuming alcoholic or nonalcoholic beverages. Results provided robust support for alcohol’s emotional and social rewards. Further, some individuals were particularly likely to experience these rewards (Creswell et al., 2012; Sayette et al., 2016). For instance, individuals high on extraversion reported greater positive mood and social bonding than individuals low on extraversion (Fairbairn et al., 2015). Moreover, social processes uniquely accounted for alcohol reward sensitivity among these high-extraversion individuals—they derived more reward from the smiles displayed by their group mates and from instances in which they shared a smile with a group mate than did individuals low on extraversion. These results extend previous studies, which demonstrated that individuals high on extraversion are more likely to endorse drinking for enhancement of positive mood and social experiences, to show that these individuals actually experience more reward from alcohol in social settings. Longitudinal studies are now needed to determine whether this differential reward sensitivity prospectively predicts the escalation of drinking over time and the development of alcohol problems. I am currently conducting such a study in 400 young adult drinkers (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03467191).

Although drinking in social settings appears to be driven by the desire to enhance positive emotions and social experiences (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995), the most compelling theory for solitary drinking is one of self-medication, in which individuals drink alone to cope with negative affect (Mason et al., 2020; Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020a). Adolescent and young adult solitary drinking is associated with drinking-to-cope motives (e.g., “because it helps when you feel depressed”) over and above social and enhancement motives (e.g., Cooper et al., 1995; O’Hara, Armeli, & Tennen, 2015). Solitary drinking is also associated with drinking during negative but not positive affect (Creswell et al., 2014), beliefs in alcohol’s ability to mitigate negative affect (Christiansen, Vik, & Jarchow, 2002), and the perceived inability to resist drinking while experiencing negative affect (Creswell, Chung, Wright, et al., 2015). Further, adolescent and young adult solitary drinking is either not related to or negatively correlated with social and enhancement motives (Armeli, Covault, & Tennen, 2018; Cooper, 1994; O’Hara et al., 2015). Thus, in contrast to social drinking, which is more strongly motivated by desire for social and emotional enhancement, solitary drinking in adolescents and young adults appears to be driven by a desire to cope with negative affect.

Future Directions

This review provides a framework for organizing research on how the social context of alcohol use in adolescents and young adults can improve our understanding of the development of alcohol problems. Additional studies are necessary to fill in some important gaps. For instance, other individual-difference factors that may be associated with solitary compared with social drinking should be explored, such as gender (Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020a) and neurobiological factors linked to variation in negative and positive emotionality (e.g., Wright, Creswell, Flory, Muldoon, & Manuck, 2019). Further, although there is some evidence for distinct alcohol problems for social compared with solitary drinking (Mason et al., 2020), there also appears to be significant overlap (e.g., risky behavior; Bersamin et al., 2012; Tucker et al., 2006). Future studies are needed to determine whether there are differential negative consequences across social and solitary settings. It is also noteworthy that the vast majority of studies in this area have been conducted on adolescents and young adults (but see Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020b, for a meta-analysis on the association between solitary drinking and alcohol problems in adults). It will be important to test the hypothesized framework in older individuals, especially given the increasing prevalence of social isolation associated with aging (Luo, Hawkley, Waite, & Cacioppo, 2012). Standardizing the definition of solitary drinking to mean drinking while no one else is physically (or virtually) present would help to further clarify associations between solitary drinking and relevant variables, given that some researchers have defined solitary drinking as drinking with nondrinking other people or among noninteracting others (see Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020a, 2020b).

In general, more rigorous tests are needed to understand the mechanisms underlying social and solitary drinking and the pathways by which drinking in each setting leads to adverse outcomes. Notably, the vast majority of studies conducted thus far on solitary drinking are cross-sectional, precluding causal interpretations. There is much that remains unknown. For instance, how do solitary drinkers experience alcohol intoxication in solitary compared with social settings? The evidence reviewed above suggests that solitary drinkers may not expect or obtain the same kind of social rewards from alcohol in social settings, but this needs to be tested in experimental studies in which the context of alcohol consumption is manipulated. Such studies would also shed light on whether solitary drinkers actually experience negative-affect relief when drinking alone and, if so, whether certain individuals (e.g., those with high negative affectivity) are especially sensitive to alcohol’s tension-reduction effects (e.g., Mohr et al., 2001). It is important to note that although young adults in prior laboratory studies have reported increased negative affect in solitary-drinking compared with social-drinking contexts (Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014), drinking alone might have been an aversive experience for the majority of these participants who (on the basis of prevalence rates) were likely social-only drinkers.

It will also be important to understand the factors that influence when solitary drinkers choose to drink in each setting. Studies using experimental mood manipulations could test the self-medication model of solitary drinking to determine whether heightened negative affect increases the preference to drink alone. Longitudinal, repeated measures designs that query individuals in real time (e.g., using ecological momentary assessment [EMA]) would be useful to better understand the antecedents to solitary drinking, how drinking alone is experienced in the moment, and the pathways by which solitary drinking leads to negative outcomes. These study designs, although still correlational, can establish temporal precedence among antecedents and consequences of solitary drinking, thus providing stronger information about the causal processes operating in the day-to-day lives of young people. For instance, using similar methodology, Mohr and colleagues (2001) demonstrated that individuals engaged in more solitary drinking on days with more negative interpersonal experiences and engaged in more social drinking on days with more positive interpersonal experiences. These types of intensive longitudinal designs would be particularly useful with adolescent populations who are not legally permitted to drink alcohol in experimental lab settings.

Much is also unknown about the social-drinking pathway to alcohol problems. Notably, in the vast majority of prior laboratory alcohol-administration studies, young adults have been asked to consume alcohol while alone (Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014). This is a highly unusual way for most young adults to experience alcohol intoxication, and this solitary setting precludes measuring many of the subjectively pleasant effects of alcohol that confer increased risk for alcohol misuse (e.g., increased sociability; Creswell et al., 2012). Use of laboratory social-drinking paradigms may permit laboratory research to become even more informative in predicting risk to develop AUD. Additionally, although individual-difference factors (e.g., genetics, personality) that predict enhanced reward from alcohol consumed in social settings have been identified (Creswell et al., 2012; Fairbairn et al., 2015), it remains unclear whether they are clinically meaningful, and longitudinal studies are needed.

Perhaps most importantly, studies should be conducted that test the hypothesized framework in its entirety within the same sample of participants, given that prior studies have tended to focus on either social or solitary drinkers. Alcohol-administration paradigms combined with EMA protocols that assess social and solitary drinkers in real time and over a long-enough time frame to detect the development of AUD symptoms would help establish the necessary directional and causal relationships presented in Figure 1. These designs would permit comparisons of the acute effects of alcohol in solitary compared with social-only drinkers across solitary- and social-drinking settings in the laboratory and real world to further test the proposed mechanisms of risk and to determine whether the hypothesized individual-difference factors differentially predict who experiences the most reward from alcohol in each setting. EMA methods could test hypothesized pathways during drinking episodes in real life and determine whether these associations predict the escalation of drinking and the development of alcohol problems over time.

In addition to the methodological implications discussed above, this framework has important conceptual and clinical implications. Conceptually, these data suggest that the context of drinking matters, with social and solitary alcohol consumption being psychologically distinct phenomena with qualitatively different antecedents and perhaps unique consequences (Cooper et al., 1995; Mason et al., 2020; Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020a). One intriguing possibility is that existing theories of alcohol use might apply more to solitary- than to social-drinking settings—for example, alcohol-myopia theory (i.e., alcohol’s tendency to constrain attention to the most salient aspects of the environment; Steele & Josephs, 1990) and appraisal-disruption theory (i.e., alcohol’s tendency to disrupt initial appraisal of stressful information; Sayette, 1993). Further, the proposed framework might also aid in our understanding of risk pathways for other drugs of abuse (Creswell, Chung, Clark, & Martin, 2015; Mason et al., 2020).

Clinically, knowing more about an individual’s pattern of social and solitary drinking would aid in understanding the purposes that drinking serves, which is useful for identifying alternative reinforcement options to target in treatment (Creswell et al., 2020). Specifically, clinicians could frame conversations around drinking contexts. When individuals feel motivated to drink alone, they could be encouraged to reflect on whether this desire is related to the experience of negative emotions, and if so, more adaptive ways to cope with such negative emotions could be implemented (e.g., distress-tolerance skills; Cavicchioli et al., 2019). Similarly, individuals could be asked to reflect on their experiences while drinking in social settings to identify why alcohol consumption in such contexts may be particularly rewarding for them. Interventions for social-drinking settings could focus on more adaptive ways to increase individual’s positive emotions and social reward without their drinking to excess (e.g., the ability to have higher quality social interactions when drinking moderately in social settings; Conroy & de Visser, 2018). Taken as a whole, the context of alcohol use deserves careful consideration as a factor that facilitates our understanding of the development of alcohol problems in adolescents and young adults.

Recommended Reading

Creswell, K. G., Chung, T., Clark, D. B., & Martin, C. S. (2014). (See References). A large prospective study showing that adolescent solitary drinking predicts the development of alcohol use disorder (AUD) symptoms in young adulthood.

Fairbairn, C. E., Sayette, M. A., Wright, A. G. C., Levine, J. M., Cohn, J. F., & Creswell, K. G. (2015). (See References). An experiment that manipulated alcohol consumption (vs. consumption of placebo or control beverages) in a laboratory social setting and found differential sensitivity to alcohol’s social rewards for individuals high on trait extraversion.

Skrzynski, C. J., & Creswell, K. G. (2020a). (See References). A meta-analytic review documenting links between adolescent and young adult solitary drinking and negative psychosocial problems, drinking-to-cope motives, and increased alcohol use and problems.