Abstract

Background Correctional facilities increasingly offer medications for opioid use disorder (OUD), including buprenorphine. Nevertheless, retention in treatment post-incarceration is suboptimal and overdose mortality remains high. Our objectives were to understand how incarcerated patients viewed buprenorphine treatment and identify modifiable factors that influenced treatment continuation post-release.

Methods We conducted semi-structured interviews with 22 men receiving buprenorphine treatment in an urban jail. Interviews were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and analyzed using a grounded-theory approach. Team members constructed preliminary case memos from transcripts, and then interactively discussed themes within respective memos. We established participant ‘typologies’ by consensus.

Results Distinct typologies emerged based on participants’ post-release treatment goals: (1) those who viewed buprenorphine treatment as a cure for OUD; (2) those who thought buprenorphine would help manage opioid-related problems; and (3) those who did not desire OUD treatment. Participants also described common social structural barriers to treatment continuation and community re-integration. Participants reported that post-release housing instability, unemployment, and negative interactions with parole contributed to opioid use relapse and re-incarceration.

Conclusion Participants had different goals for post-release buprenorphine treatment continuation, but their prior experiences suggested that social structural issues would complicate these plans. Incarceration can intensify marginalization, which when combined with heightened legal supervision, reinforced cycles of release, relapse, and re-incarceration. Participants valued buprenorphine treatment, but other structural and policy changes will be necessary to reduce incarceration-related inequities in opioid overdose mortality.

Highlights

Participants have varied goals for post jail release OUD treatment continuation.

Past experiences with OUD treatment after jail highlight many structural barriers.

The legal supervision of parole can reinforce cycles of use and re-incarceration.

1. Introduction

Reducing opioid overdose deaths in the United States (US) will require specific attention to improving opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment in criminal justice settings. Increasing severity along the spectrum from opioid use to opioid use disorder is associated with greater criminal justice involvement. (Winkelman et al., 2018). An estimated one-third of heroin users in the US pass through correctional facilities annually (Boutwell et al., 2007). In the first two weeks following release from incarceration, the rate of drug overdose death is up to 129 times greater than that of the general population (Binswanger et al., 2007, Krinsky et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2012). In 2014, nearly 10 % of Massachusetts’s opioid overdose decedents had been released from incarceration in prior 12 months (Larochelle et al., 2019). Incarceration is a critical period where evidence-based OUD treatment could be initiated, but this has been uncommon in the US to date (Frisman et al., 2012).

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) are safe, effective, and can be integrated into criminal justice settings (Bart, 2012). Data from England and Australia demonstrate that people with OUD who leave incarceration receiving MOUD have 75 % lower mortality in the month following release than those who are not taking MOUD (Marsden et al., 2017; Degenhardt et al., 2014). However, the protective effect of exposure to MOUD during incarceration was not observed after 4 weeks post-release in these studies (Marsden et al., 2017; Degenhardt et al., 2014). Clinical trials of buprenorphine and methadone treatment in US correctional facilities demonstrate that starting MOUD prior to release increases treatment entry post-release (Gordon et al., 2017, 2014; Gordon et al., 2008; Magura et al., 2009). However, one trial of buprenorphine treatment initiation in prison demonstrated that in the 12 months following release, participants who started buprenorphine in prison received only 66 days of treatment, while those referred to buprenorphine at the time of release received only 22 days (Gordon et al., 2014). Thus, additional work is necessary to assure long-term engagement in MOUD post-release and to maintain the benefits of initiating MOUD during incarceration.

Buprenorphine treatment is particularly promising for correctional facilities because it is less stringently regulated than methadone treatment. In this paper we refer to the more widely used oral formulations, but new long-acting injectable buprenorphine formulations could also provide unique benefits (Vorspan et al., 2019). US physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants who receive a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Agency may prescribe buprenorphine from any office-based setting. Only providers at licensed opioid treatment programs may prescribe methadone for OUD treatment (Rettig and Yarmolinsky, 1995). Qualitative data suggest that buprenorphine treatment is acceptable to people with OUD and criminal justice involvement – and may even be preferable to methadone for some (Fox et al., 2015; Awgu et al., 2010). However, treatment continuation post-incarceration is impeded by structural barriers to care and beliefs about OUD recovery that emphasize willpower more than medication (Fox et al., 2015; Velasquez et al., 2019).

This study examined the attitudes and beliefs about MOUD continuation post-incarceration among people who were receiving buprenorphine treatment in jail. Prior research has highlighted structural barriers, such as insurance access, but we were specifically interested in peoples’ recovery goals and plans for OUD treatment post-release (van Olphen et al., 2006; Velasquez et al., 2019). These data are critical for developing interventions to support buprenorphine continuation post-incarceration that draw upon patients’ individual supports and address potential concerns about MOUD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and sample selection

From November 2018 to May 2019, we conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with a convenience sample of 22 incarcerated men in a New York City jail. The jail system offers initiation or continuation of buprenorphine treatment for people with OUD. Inclusion criteria for study participation were: (1) English- or Spanish-speaking; (2) at least 18 years old; (3) currently receiving buprenorphine treatment; (4) being within one year of scheduled release; and (5) agreeing to a follow-up interview within 6 months of release. Health care providers (of NYC Health + Hospitals Correctional Health Services led by the MOUD program director) introduced the study to their patients during scheduled buprenorphine treatment visits. Following patients’ oral assent to share contact information, health care providers gave the research team a list of potential participants. The research team then requested a correctional officer to ask potential participants to report to the medical clinic. At the clinic, the lead author (a physician) described the study to participants and elicited informed consent prior to conducting an interview. Forty-six participants were identified as potential participants, 20 declined to report to the clinic when called (thus consent and the research project were not discussed), and 4 declined participation after the interviewer described the project (two stated they were late for dinner; one expressed concerns about confidentiality; one stated that he was not interested). The study received institutional review board approval.

2.2. Data collection

Interviews were conducted in a private space within the jail’s medical clinic. Correctional officers maintained visual contact with participants through a window but could not hear interviews. A male physician interviewer (WV) used a semi-structured interview guide based on the extant literature and the goals of this study (Velasquez et al., 2019; Fox et al., 2015; Binswanger et al., 2011). Interview domains included: 1) History of drug use including illicit use of buprenorphine and/or methadone; 2) History of substance use disorder treatment or rehabilitation, especially MOUD; 3) Experiences, attitudes, and motivations for buprenorphine treatment in jail; 4) Past barriers to treatment; and 5) Expectations regarding treatment continuation post-release. Interviews were audio-recorded to a digital file, stored on an encrypted password protected computer, professionally transcribed without participant identifiers, and uploaded into Dedoose®, an internet-based platform for qualitative data analysis. Participants were compensated with $20 worth of socks and underwear for completion of the interview. A second interview was planned for the period after participants were released from incarceration, but only data from pre-release interviews will be presented in this article.

2.3. Data analysis

Analysis used a grounded theory approach, which allows theory generation based on emergent findings from the data. The research team used the constant comparative method to discuss similarities and differences between themes and typologies and across cases (Charmaz, 2006). The team included two male physicians and two female PhD qualitative researchers. Each team member first reviewed the recorded interview and written transcript of a single participant case and constructed a preliminary case memo including salient quotes. The team then met to discuss identification of both deductive and early inductive themes within their respective case memos. Following significant convergence on theme identification among all team members’ memos, individual analysts repeated this process with subsequent participant cases. In regular analytic team meetings, team members discussed unclear or discordant findings between analysts until a clear and consistent group of themes and subsequent ‘typologies’ were iteratively defined with consensus (Kluge, 2000).

3. Findings

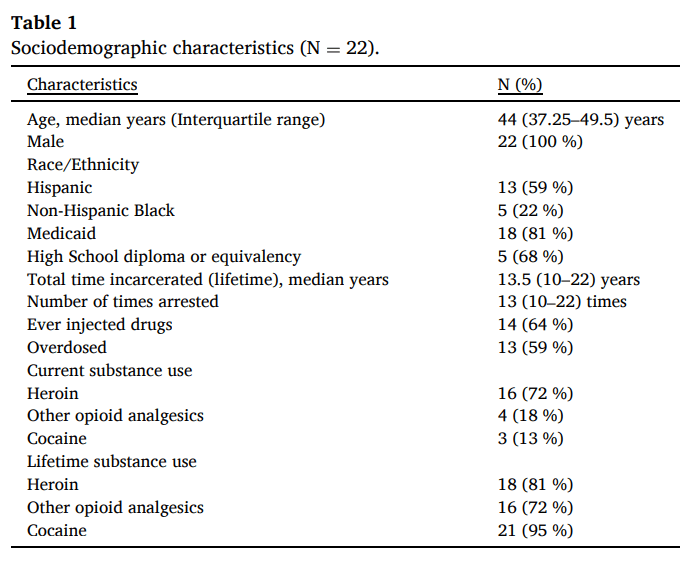

Participants were all men between the age of 29 and 57. The majority had public insurance or were uninsured prior to incarceration. They also had long histories of substance use (with nearly all having overdosed at least once) and criminal justice involvement (see Table 1). More than half were people of color.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics (N = 22).

3.1. Overview

Broadly, three participant typologies emerged regarding individuals’ expectations of buprenorphine continuation upon release. Groups were organized and named based on treatment goals: Curative - individuals who planned on continuing to take buprenorphine regularly, engage in medical care, and abstain from opioid use, which they perceived would help them overcome OUD; Management - individuals who planned to take buprenorphine on an as-needed basis, which included buprenorphine prescribed by a doctor or acquired non-medically. These individuals expressed desire to reduce their opioid use and better manage symptoms of withdrawal and/or tolerance; and Not Treatment Focused – those who did not care to continue buprenorphine after leaving jail and planned on returning to illicit opioid use post-release.

3.2. Curative: “I just want a normal life”

We identified 14 of the 22 individuals best described as being in the Curative group. Generally, men in this group planned to continue buprenorphine by engaging in medical care. They had goals of abstinence from illicit opioid use and planned to take buprenorphine as prescribed with eventual cessation of treatment. “Pat”, a new father, held a typical attitude toward treatment. He had experiences with methadone during previous incarcerations but never continued treatment outside of jail because of stigma around methadone and methadone clinics:

“I'm going to use it [buprenorphine] the way the doctor prescribes because I've been doing it the way they taught me to take it here. And it's been going fine for me. So, I'm not going to start doing something new.”

Individuals in this group often identified strong social supports, citing returning to non-drug using family members, partners, and friends both as reasons for reducing opioid use and as potential sources of psychosocial support. Post-release plans often involved more structured programs to address substance use. Almost all planned to return to previous buprenorphine providers, establish care with a new provider, or enroll in a substance use treatment program. An example of the types of supports identified by individuals in the Curative group was given by “Jorge,” a middle-aged tradesman, who desired to decrease his substance use for his family:

“I’ve been shooting heroin for a lot of years and I got two beautiful children that love me. That’s my inspiration. My father also needs me. He’s getting older now. My mother needs me. She’s getting old too. And, I’ve been taking care of them since 1996. And it’s just time that, like, you have to grow up, man.”

Curative interviewees frequently referenced a dichotomy between living a “normal life”, mentioning regular employment, community involvement, and stable housing, and a “drug life”, which they associated with financial instability, legal problems, pressure to acquire opioids to mitigate withdrawal, and straining ties with their community. Participants were strongly motivated by the chance to achieve what was often referred to as “a normal life”. For example, “John” expressed frustration in the all-encompassing effect of his substance use:

“I got to a point in my life where I just got sick and tired of the 24 -h job it is to use. I mean it is a 24 -h job. I got tired of getting up in the morning worrying about when I’m going to get my next fix. Or am I going to get busted? I got tired of going to sleep and tossing and turning about, you know? I got to get myself a bag or I got to go out right now and I got to make money. I got tired of all that."

Participants in this group also referred to substance use as stigmatized and a source of shame. For some participants shame led to escalating substance use, while others saw shame as a motivator for quitting. Less often, but still common, the stigma for many individuals in this group extended to MOUD. These participants desired to be “off everything,” stating a preference for substance-free recovery. “Benjamin”, a man in his 50′s, started buprenorphine in jail a month earlier and believed it would be a faster and safer route to complete opioid abstinence than his prior experiences with methadone:

“I switched over to the [buprenorphine] because I feel that it’s gonna be easier and better for me to transition of leaving everything alone. With the methadone, it’s… I’ve been there, done that, didn’t really want to quit. I know the trials and tribulations I’m gonna go through. Now my mind, I have myself where I want to get off, I’m finished with it. The [buprenorphine], I can ease my way out.”

Nearly all participants felt positively about jails offering buprenorphine treatment. Some participants even described their time in jail as beneficial or therapeutic as they were forced out of unhealthy environments. For some participants incarceration was the first time that they had access to treatment. Some participants stated that the fear of overdose in the age of fentanyl was a compelling reason for seeking treatment and that “drug life” was no longer enjoyable and too dangerous. Overall, individuals in the Curative group hoped that buprenorphine treatment would be a vehicle back to family, employment, and legal/housing stability – a “normal” life.

3.3. Management: “It depends on how I’m feeling”

We identified 7 of the 22 individuals in the Management group. The men in this group valued structured buprenorphine treatment less than the medication itself. These participants planned on taking buprenorphine on an as-needed basis, and predicted that they would buy buprenorphine from street markets upon release. They also expressed a desire to decrease but not stop illicit opioids, avoid the criminal justice system, and independently manage symptoms of withdrawal with buprenorphine. “Micky”, a middle-aged man who frequently returned to drug use after brief episodes of MOUD, expressed this hope:

"My goal is to stay out of jail. That’s the first thing. This [buprenorphine] is helping me because I’m not getting cravings. This is going to help me not think about going back to no drugs or anything. But I mean after I achieve that, I might want to try to – I don’t know… It depends on how I’m feeling…If I’m doing better and I’m making more money, I might go back to dope."

Few of the men in this group had clear plans for treatment, housing, or drug-free social networks to which they could return. The majority had strong family histories of drug use. Participants in this group reported high levels of criminal justice system involvement including more prior arrests and participation in criminal gangs than the Curative group. The inevitability of drug use was reflected in this quote from “George,” a man in his 30′s who sold drugs and had been involved with gangs since his early teens:

“Me being a gang member, I'm not allowed to have heavy drugs. But, I want to sell anything for anything just to get that high… I should just go ahead with the [buprenorphine], but I know that my wants are not stronger than that urge to use. It is not even on purpose, it’s just one minute I just find myself like, ‘Oh, I'm going to do it.’"

Predominantly the men in this group planned on using buprenorphine to manage opioid withdrawal (and were supportive of its use within correctional settings) or to take it temporarily when their drug use disrupted their daily lives. Many had had years of experience using the medication this way.

3.4. Not Treatment focused: “I don’t make plans.”

We identified only one of the 22 individuals in the Not Treatment Focused group. While there was only one member of this group, he was a notable exception to the other two typologies that offered important insight into other opioid use behavior. This individual had no plans to continue MOUD or even take buprenorphine upon release and planned to return to opioid use.

The participant planned to taper off buprenorphine immediately after being released so that he could resume using heroin. His primary substance used was crystal meth, and he used heroin only occasionally and therefore did not identify strongly as having OUD. He stated that he told doctors at the jails that he used heroin regularly so that he could get buprenorphine for the euphoric effect.

“I started [buprenorphine] to get high. It gets me high for about three days. Then I just feel normal, a little sleepy. I only use it while I am here [Rikers Island]. I use it to get away. I would never use other drugs because being here, it fucks up your high.”

Individuals from the Curative and Management groups also identified past instances when they had left jail being best described as Not Treatment Focused. This was especially true before they had encountered buprenorphine, as nearly all our interviewees found issue with methadone for various reasons. Similarly, there were many individuals in the Curative group who described times in the past in which their “willpower” and social networks were such that they could not have envisioned a path toward abstinence. “Benjamin,” an older man who only recently started buprenorphine, described periods of his life that were consistent with Not Treatment Focused typology:

“When I went home, I’m wasn’t really interested in the meth[adone] program because I know the dope man right up the block to where I live at. When I came back to jail, same situation. I just want my meth[adone] to hold me until I get out, so I can go see my mans with the dope. This time, I don’t want to see my mans with the dope.”

3.5. Common themes among all groups: Legal and structurally barriers to care

Most participants had long histories of criminal justice involvement and had previously attempted to reduce opioid use after being released from incarceration. Most participants took non-prescribed buprenorphine while incarcerated. Some participants maintained years of opioid abstinence from strictly illicit buprenorphine sources having forgone professional treatment due to the burden of receiving MOUD in structured programs. Many participants also cited social structural barriers to continuing OUD treatment post-release, such as unstable housing. Another common barrier to care was the parole system, which influenced participants’ drug use and recovery in complex ways.

Participants highlighted parole infractions that they perceived to be arbitrary and counter-productive to their OUD treatment goals. Participants explained that parole violations frequently led to re-incarceration, which took them away from their support systems, including OUD treatment programs. Others spoke of the “pointlessness” of staying abstinent once they received a parole violation and knew they would return to jail. “Leon”, an older man who had been incarcerated dozens of times for parole violations, explained:

"Parole keeps violating me. You know I just keep getting my violations and nothing that I accomplish, the little things that I have in my little room, I lose it. You know I want to live a normal life man. I’m just tired of suffering because that's all I know is how to suffer.”

“Bob”, similarly, used what he saw as arbitrary parole violations as reasons to stop MOUD and return to opioid use:

“I’ve been on parole since 2011. So all of the 30-day rehabs that I’ve been in since then and a couple of psych wards, once I went on the run from parole, it’s over. I don’t care about anything anymore. When I’m on the run, why should I care? I know I got to go back to jail.”

4. Discussion

Our study of jail-based buprenorphine treatment suggests that individuals participate in buprenorphine treatment in jail with different goals for continuing treatment after their release. Analyzing similarities across participants allowed us to create composite “types” that highlight post-incarceration expectations, as well as, common supports and challenges that impact OUD treatment. While many participants, like those within our Curative group, professed commonplace goals of stopping illicit opioid use and living a “normal life,” many others (Management and Not Treatment Focused groups), simply wanted to decrease their opioid use, mitigate symptoms of withdrawal, and stay out of jail. Acknowledging and accepting these disparate treatment goals have important implications for OUD treatment and overdose prevention during and post-incarceration.

Opioid abstinence is often a singular goal for OUD treatment in the United States, but this view only represented the priorities expressed by participants in the Curative group. Providing pre-release discharge planning and linkage to community treatment providers post-release, which is the standard of care at the study setting, could facilitate treatment continuation for participants with these goals. Clinical trials and international experiences demonstrate feasibility of treatment initiation during incarceration and community linkage post-release (Malta et al., 2019). However, our Management and Not Treatment Focused participants were less interested in continuing professional buprenorphine treatment and may drop-out of treatment post-release. These participants valued treatment during incarceration because it prevented withdrawal and reduced illicit opioid use, but they also recognized that return to opioid use was likely, and they had few positive supports to help them achieve recovery. New approaches to engaging these participants in care will be necessary. These participants had long histories of cycling through jails and prison, which did not appear to change their patterns of substance use in meaningful ways. Treatment during incarceration would still provide benefits, discussed more below, but a focus on harm reduction at the time of release may be more consistent with their buprenorphine treatment goals. Low-threshold buprenorphine treatment could facilitate entry into treatment when participants are ready and make it easy for patients to re-engage in care if they drop out (Jakubowski and Fox, 2019). Systems of community supervision should recognize that not everyone with OUD will be able to reach abstinence, necessitating alternatives to cyclical and punitive parole and probation systems that punish people for ongoing substance use.

For participants in the Curative group who expressed goals of stopping all opioids, the singular emphasis on abstinence could also introduce risk, if it contributed to premature buprenorphine cessation. OUD is a chronic condition and mortality increases after treatment cessation (Sordo et al., 2017). Participants expressed that buprenorphine would be easier to stop than methadone treatment. It is unclear how much treatment cessation is driven by attitudes toward medications, difficulties with treatment access, costs or inconvenience, or other challenges during community reentry; however, other interviews with formerly incarcerated individuals have documented reluctance to use buprenorphine treatment because some believe that willpower alone should be sufficient for recovery (Fox et al., 2015). Our participants also perceived employment and supportive family as facilitating treatment continuation, and housing instability or conflict with parole or probation officers as preventing continuation, so creating an environment conducive for recovery during community reentry will be essential for treatment continuation. Nonetheless, additional work will be needed to prevent premature discontinuation of MOUD.

For participants in the Management and Not Treatment Oriented groups, benefits from even temporary treatment in jail justify assuring access to treatment. Overdoses do occur during incarceration and can be prevented by providing MOUD access during incarceration (Larney et al., 2014). Though treatment may be stopped post-release, treating OUD during incarceration can also reduce demand for contraband opioids and create more orderly facilities (Johnson, 2001). One community-based study (Kayman et al., 2006) suggests that goals expressed at the beginning of methadone treatment may not accurately predict who continues or drops out of treatment; therefore, participants who express ambivalence about long-term treatment may subsequently decide to continue treatment if they derive benefit from it. Most of our participants displayed fluidity over their lifetimes between Curative, Management, and Not Treatment Focused modes of thinking. Thus, a positive experience starting MOUD in jail could lead to changes in recovery trajectory. Assuring access to buprenorphine treatment during incarceration can still be a way to engage a hard-to-reach population in care.

Participants’ perception that parole was a barrier to reducing opioid use is a novel finding for the buprenorphine treatment literature. Criminal justice involvement is a common experience for people with opioid use disorder (Winkelman et al., 2018). Interviewees in all three groups reported that parole conditions were arbitrary, harsh, and uncoordinated with post-release OUD treatment plans, which contributed to their marginalization. Participants reported that parole sanctions caused them to lose any progress they had made in gaining life stability or acquiring material possessions and often geographically separated them from familial and community support networks. Prior cohort studies of buprenorphine treatment found that individuals who were supervised by parole or probation had similar outcomes to other buprenorphine patients (Gordon et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2014). However, parole and probation supervision itself, especially newer “intensive supervision programs” like Hawaii's Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE), have been shown to decrease drug use (Lattimore et al., 2018). Parole programs associated with even minimal ancillary services like case management also have been shown to decrease drug use (Prendergast, 2009). Thus, our participants may represent a subgroup with severe long-standing addiction who are harmed more by sanctions than helped. However, our study design does not allow us to tease out differences between participants. Hypotheses regarding who is helped by intensive supervision could be tested in larger studies.

Our study has limitations. Sampling was by convenience and physicians referring potential participants may have prioritized certain personalities (for example, individuals willing to discuss their drug use). Twenty individuals declined to speak to the research team and four more declined to be interviewed after starting the consent process. It is possible that people who would have fallen within the Not Treatment Focused group were less willing to speak with medical staff than other groups. Additionally, we sought to identify patterns or “types” in this study to facilitate intervention development, but treatment decisions for individual patients should be based on their unique goals and preferences.

This study points to a paradigm in which individuals in the Curative group largely sought to reconnect with stable social systems and escape the destabilizing cycles of drug use, arrests, incarceration, and parole/probation. However, for a sizable minority in the Management and Not Treatment Focused groups, the aspirational “normal life” described by the Curative group seemed out of reach. Nonetheless, participants highlighted the futility of these cycles of reincarceration, which often marginalized them from social and material wellbeing. Ultimately, buprenorphine treatment in jail can provide a pathway to abstinence for some, but there is not one singular pathway to stability. Less punitive and destabilizing ways of engaging individuals in care must be considered or we risk suffering the consequences of dangerous and harmful histories repeating themselves.