Abstract

Youth self-reports are a mainstay of delinquency assessment, however, making valid inferences about delinquency using these assessments requires equivalent measurement across groups of theoretical interest. We examined whether a brief 10-item delinquency measure exhibited measurement invariance across non-Hispanic White (n = 6064) and Black (n = 1666) youth (ages 10-11 years old) in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development℠ Study (ABCD Study®). We detected differential item functioning (DIF) in two items. Black youth were more likely to report being arrested or picked up by police than White youth with the same score on the latent delinquency trait. Although multiple covariates (income, urgency, and callous-unemotional traits) reduced mean-level difference in overall delinquency, they were generally unrelated to the DIF in the arrest item. However, the DIF in the arrest item was reduced in size and no longer significant after adjusting for neighborhood safety. Results illustrate the importance of considering measurement invariance when using self-reported delinquency scores to draw inferences about group differences, and the utility of measurement invariance analyses for helping to identify mechanisms that contribute to group differences generally

1 Introduction

Delinquency refers to the commission of illegal or socially inappropriate behaviors by youth—especially behaviors that violate the rights of others (e.g., stealing, destroying property, violence)—and is associated with a variety of important outcomes including adult criminal behaviors, substance use problems, victimization, educational and employment difficulties, and mental health problems (Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2007; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006; Maclean et al., 2014; Odgers et al., 2008). In addition, youth that report engaging in any delinquent behaviors are likely to engage in multiple types of delinquent behaviors (e.g., property offenses and violence) and so there is a large literature that conceptualizes delinquency as a unidimensional construct (Espiritu et al., 2001; Loeber et al., 2009). Consequently, studying the risk factors and consequences of delinquency in youth using longitudinal designs is critical for better understanding psychosocial adjustment. Self-reports of delinquency are particularly valuable as youth provide information about their own activities, circumnavigating the biases of other sources of information on delinquency (e.g., police reports and court records) (Farrington et al., 1996; Krohn, Thornberry, Gibson, & Baldwin, 2010; Piquero, Schubert, & Brame, 2014). For example, in contrast to self-reports, official records require detection and interaction with law enforcement. A substantial amount of crime is not reported, however, and many crimes reported or brought to the attention of law enforcement are not officially recorded. Rates of self-reported delinquency are thus much higher than those from official records (Ahonen et al., 2017; Theobald et al., 2014). Indeed, most adolescents (e.g., 55% in the United States; Enzmann et al., 2010) report engaging in some form of delinquency, though only a small proportion report severe delinquent activity (e.g., 2.1% report breaking and entering; He & Marshall, 2009).

Self-reports of delinquency also exhibit weaker associations with socioeconomic status (SES) and race than do official records of delinquency, further suggesting less bias than is present in official records based on interactions with law enforcement and other authorities. Although the associations between delinquency and socio-demographic variables are weaker for self-reported delinquency relative to official records, the pattern of associations is similar. Higher delinquency is associated with male sex, Black and Hispanic race and ethnicity, lower SES, and residence in poor and urban neighborhoods (Bragga, Brunson, & Drakulich, 2019). One consistent difference in the rates of self-reported delinquency is between Black and White youth. This racial difference could in part be due to disproportionate exposure of Black youth to risk factors for delinquency, including low income, neighborhood crime, less school resources, and racial bias (Barrett et al., 2014; Brody et al., 2001; Gibbons et al., 2004, 2020). However, measurement bias could also contribute to these mean-level differences across Black and White youth. Self-report delinquency questionnaires often ask youth to report on their behaviors (e.g., stealing, bullying), and the consequences of these behaviors (e.g., being suspended and arrested). The latter introduce the potential for measurement bias stemming from the structural racism and systematic biases present in American society.

Specifically, White and Black youth are viewed differently by authority figures such that Black youth are perceived by teachers and adults to be more oppositional and rule-breaking and more deserving of harsher discipline (Neal, McCray, Webb-Johnson, & Bridgest, 2003; Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). Black youth are also perceived to be older and more mature than same-age White peers, and consequently more culpable for misbehavior (Epstein, Blake, & Gonzalez, 2017; Goff et al., 2014). Disciplinary actions are thus more frequent and severe for Black youth than White youth beginning in preschool (Gilliam, 2005), a difference that persists into adulthood, and extends to interactions with police and the criminal justice system (Brame et al., 2014; Doerner & Demuth, 2010; Feldmeyer & Ulmer, 2011).

Furthermore, while some respondents may be concerned about stigma, negative evaluation, and unfair treatment following the disclosure of delinquent behaviors, such feelings might be more prevalent in members of social groups targeted for negative stereotypes associated with crime. These concerns, along with differences in cultural attitudes about specific behaviors, could shape how different respondents interpret and respond to questionnaire items about delinquency, especially if these questionnaires are explicitly presented to respondents as measuring delinquency or some other negatively evaluated characteristic. To the extent that the measurement of delinquency is biased across certain groups, the validity of inferences that can be drawn using delinquency assessments will be undermined, especially in the context of examining group differences (e.g., group differences may be spuriously exaggerated).

1.1 Item Response Theory and Differential Item Functioning

Given the multiple factors that can contribute to bias in measurement, it is critical to identify questions about measurement bias that can be translated into quantitatively testable hypotheses and apply relevant methods to examine the extent to which items and measures are psychometrically equivalent across groups. Tests of measurement bias are often conducted as tests of differential item functioning (DIF), a term from the item response theory (IRT) literature. IRT is a measurement framework that includes a wide range of latent variable models that provide information about psychometric functioning at the item and test level (de Ayala, 2009; Embretson & Reise, 2000).

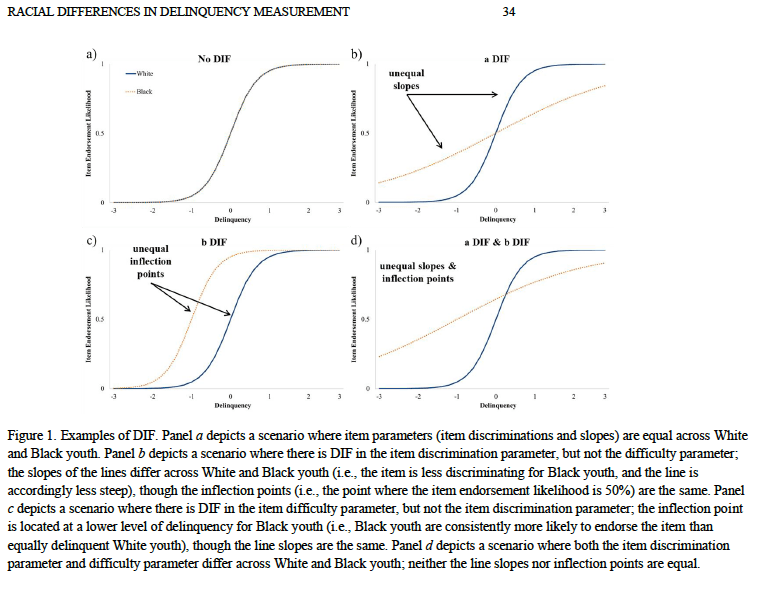

The two-parameter logistic model (2PL) is the item response model used for dichotomous responses, depicted in Figure 1 panel a. IRT analyses are based on modeling the likelihood of a specific item response as a probabilistic function of participants’ scores on the latent construct of interest and a series of item parameters. Discrimination parameters (a) are analogous to factor loadings and index how strongly an item is related to the latent factor, represented by the slope of line between the latent trait and probability item response. Difficulty parameters (b) are similar to intercept and threshold parameters and capture the point along the latent trait where the likelihood of endorsing an item is 50% (i.e., the item inflection point) (Wirth & Edwards, 2007).

DIF is used to determine when the discrimination or difficulty parameters differ meaningfully across groups. Four different DIF scenarios are depicted in Figure 1, which includes a series of item characteristic curves (ICCs) illustrating how the probability of item endorsement (the Y axis) changes across levels of the latent factor or trait (the X axis). DIF is problematic because it places groups on different metrics, even though the latent factors are ostensibly tapping into the same construct using the same instrument. This renders group comparisons—either of means or associations with external variables—potentially invalid as observed differences could be due to DIF (i.e., a methodological artifact), which inappropriately increases or decreases observed group differences.

The identification of DIF can have different implications depending on its nature and magnitude. Some statistically reliable DIF will usually be identified if the sample size is large enough (Marsh et al., 2018), but it may not relate to any theoretically relevant processes across groups or be modest in magnitude. In such instances, the DIF is typically not considered meaningful except for adjusting scores to ensure unbiased group comparisons. In some cases, however, there is a theoretically plausible explanation for DIF, and it may be possible to statistically account for DIF with meaningful covariates. In this situation, the DIF can be a signal for mechanistic processes across groups that influence the latent trait. For example, race is not typically conceptualized as an explanatory variable per se, rather it serves as a proxy for mean-level differences on a variety of processes that differ across different racial categories.

Notably, DIF and group differences are distinct issues focused on different questions and entail different analytic approaches. The presence or absence of DIF has no inherent implications for whether there are true group differences on the latent construct, but if DIF is identified, observed group differences may not be accurate until the DIF has been addressed. Remedies for dealing with DIF include revising the items, removing them from the assessment, ignoring the DIF if it is largely inconsequential, or adjusting scores by incorporating DIF into a measurement model (Clark & Donnellan, 2021).

1.2 Delinquency, Race, and DIF in the ABCD

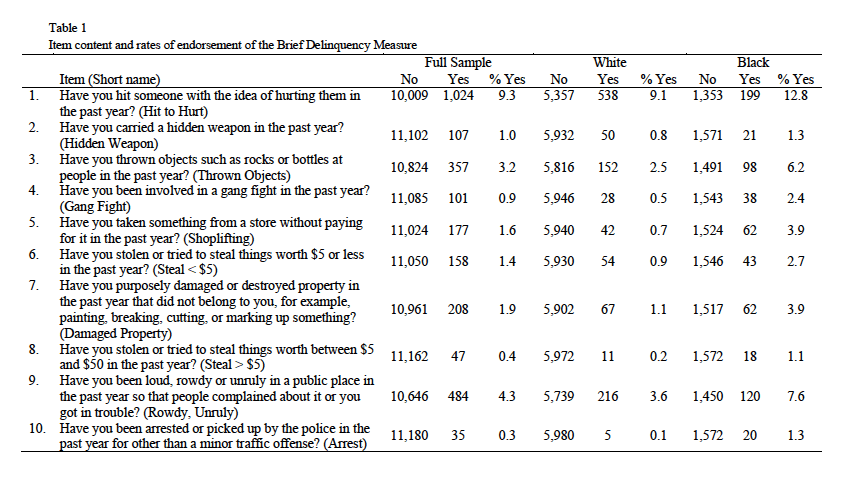

The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development℠ Study (ABCD Study®) assessment includes a Brief Delinquency Measure (BDM) that consists of 10-items designed to measure general delinquency (Table 1). A review of ABCD instruments by members of the ABCD Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) Working Group flagged two items that had the potential for bias, specifically, items that asked about: 1) Whether adults complained about the youth being rowdy and loud in public; and 2) Whether the youth was arrested or picked up by the police (items 9 and 10 in Table 1). The rationale for the potential bias was that these items reference responses by adults and authorities to the child rather than specific delinquent acts. Given the evidence for biased responses by adults to White versus Black youth, it was plausible that these items would exhibit some form of DIF.

We also wanted to follow-up the detection of any DIF by examining whether any relevant covariates could account for the DIF and mean-level differences in overall delinquency between White and Black youth. We identified four relevant covariates: household income and neighborhood safety (two contextual variables), and personality traits related to urgency (a facet of impulsivity) and callous-unemotional interpersonal style (two person-level variables). Household income and neighborhood safety are each associated with greater delinquency and show large mean differences across Black and White families in the United States (Henry et al., 2019; Leventhal et al., 2015). While economic disadvantage puts constraints on all families, Black families are more likely to live in neighborhoods with higher crime rates than income-matched White families, in part, due to lower levels of government investment in these areas which creates an environment that can negatively impact child and adolescent development (Henry et al., 2019). For example, higher neighborhood danger and crime is associated with greater victimization and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents (Leventhal et al., 2015). Urgency and callous-unemotional (CU) traits are personality characteristics consistently associated with delinquency, but they exhibit relatively small mean differences across Black and White youth (Horan et al., 2015). Personality traits provide a person-level variable against which to contrast the effects of the contextual variables of income and neighborhood safety as sources of influences on delinquent behavior. Given prior findings, we made the following predictions: 1) Rates of observed self-reported delinquency would be higher in Black youth compared to White youth. 2) DIF would be present for items that entailed adult reactions to child behavior, specifically, being loud and rowdy in public and being arrested or detained by police. We predicted the DIF was most likely to be present for the difficulty parameter, with Black youth exhibiting lower difficulty parameters than White youth (i.e., endorsed by Black youth at a lower level of latent delinquency than White youth). 3) We anticipated that lower household income, low neighborhood safety, CU traits, and urgency would be associated with higher overall delinquency. While household income and neighborhood safety have been found to differ between Black and White youth (Henry et al., 2019; Leventhal et al., 2015), scores on indices of CU traits and urgency do not differ substantively between Black and White youth (Hawes et al., 2020; Watts et al., 2020). Therefore, we predicted that only household income and neighborhood safety would account for at least some of the race differences in overall delinquency and item DIF.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample

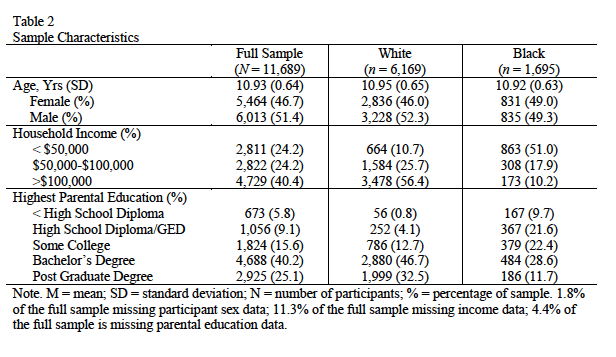

We used data collected from the ABCD Study, a large longitudinal study of youth recruited from 21 research sites across the United States (Barch et al., 2018; Garavan et al., 2018b; Volkow et al., 2018). Although not nationally representative, study sampling was carried out so that the sample would accurately reflect the diversity of the national population, thereby greatly increasing the generalizability of its findings (Garavan et al, 2018). For the current analysis, data were collected from visits between August 30, 2017 and January 13, 2020 (n = 11,311; 1-year follow up), and the data used in this report is publicly available and came from ABCD Release 3.0, DOI: 10.15154/1519007. Approximately half (58.4%) of the sample was White, with the remaining participants identifying themselves as African American/Black (20.3%), or Asian (6.9%); 20% of participants identified as Hispanic (data on ethnicity was missing for 1.4% of the sample). Given our aim to understand racial bias regarding Black youth, analyses focused on the non-Hispanic White (n = 6,064) and non-Hispanic Black (n = 1,666) youth. Further details regarding the characteristics of the sample can be found in Table 2.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Delinquency.

The Brief Delinquency Measure (BDM) was included in the ABCD Follow-Up 1 and subsequent annual visits to provide a brief assessment of a range of delinquent behaviors varying in severity. Ten items were selected from a version of the Self-Reported Delinquency Scale (Elliot, Huizinga & Menard, 1989) adapted for the Pittsburgh Youth Study and the Pittsburgh Girls Study (Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & White, 2008). Youth were asked to report on if they had ever engaged in or experienced 10 behaviors. The 10 items from BDM are presented in Table 1. In terms of validity and reliability, the correlation between total scores on the BDM and a 48-item version of the SRD was r(985) = .60, p < .001, and the 1-year rank-order (i.e., test-retest) stability of BDM total scores was r(6527) = .43, p <.001. BDM total scores also exhibited a consistent pattern of associations with measures of related constructs including parent reports of Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach et al., 2000) Externalizing [r(4508) = .19, p < .001], Rule Breaking [r(4508) = .20, p < .001], and DSM 5 Conduct Disorder [r(4508) = .22, p < .001] scores; teacher report of externalizing problems [r(4347) = .20, p < .001]; and child reports on the Inventory of Callous Unemotional traits [r(986) = .26, p < .001] (Kimonis et al., 2008) and prosocial behavior [r(11,181) = -.22, p < .001] (Goodman, 1997). The effect size for some of these correlations are attenuated due to the low variance of the BDM scores, reports provided by different informants across measures, and the length of time between the completion of the two measures.

2.2.2 DIF Covariates.

Parents reported on the total combined household income for the past 12 months. Household income was categorized into 10 separate categories (i.e., 1=less than $5,000 to 10=$200,000 or more). Parents reported on neighborhood safety and crime using items from the PhenX Toolkit (Zucker et al., 2018) using a five-point Likert scale rating (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree).

A four-item youth-report measure of CU traits was developed to index lack of empathic concern, shallow affect, and low guilt within the ABCD study (Hawes et al., 2019). This measure of CU traits was derived from three items (reversed) from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997) and one item from the CBCL. Scores were computed using a traditional summed score approach. This brief scale has demonstrated adequate convergent and discriminant validity (Hawes et al., 2020).

A 20-item youth short version of the UPPS-P, developed for use in the ABCD study (Barch et al., 2018) was administered via self-report at baseline to index trait urgency. Due to their associations with delinquency (Watts et al., 2020), we focused analyses on the Urgency (combination of items from the Negative and Positive Urgency) subscales. We have reported on how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures in the study.

2.3 Data Analytic Strategy

We began by examining the psychometric properties of the BDM in the full sample, and then separately in White youth and Black youth. First, we used item factor analysis (IFA; Wirth & Edwards, 2007) to determine if the BDM scale exhibited unidimensionality (or essential unidimensionality), an assumption of many item response models. Second, we fit 2PL item response models (de Ayala, 2009) to the BDM items to provide initial estimates of the item discrimination and difficulty parameters. This study was not preregistered. The remainder of the analytic strategy section has been condensed for readability, but a fuller explanation of the methods used here can be found in the online supplement (https://osf.io/g87b5/?view_only=4061f6809d0f45a4b5aa231ec1da4c4f). Analysis code for this study are available by emailing the corresponding author.

2.3.1 Testing for DIF.

We then tested for DIF in the BDM items across White and Black youth using two variants of the improved Wald Test for DIF (Cai, 2008; Woods, Cai, & Wang, 2012). First, all items were simultaneously tested for DIF in an initial sweep. An advantage of the “DIF sweep” method is that all items are simultaneously tested for DIF; however, it is prone to an inflated false-positive rate (Woods et al., 2012). Thus, this approach was used here primarily to identify anchor items, and flag items that might contain DIF across groups. More focused, robust tests of DIF were subsequently conducted based on these initial results. All items that showed no evidence of DIF in the initial sweep were constrained to equality across groups in the subsequent DIF model, while all items that exhibited evidence of DIF were freely estimated across groups. Finally, one more DIF model was run in which the item parameters that did not exhibit DIF in the prior model were constrained to equality across groups, while those item parameters that did evidence DIF were freely estimated. This last model was estimated to identify the most parsimonious multi-group model for the BDM items that still accounted for DIF, and because including more anchor items increases the power and robustness of DIF tests.

2.3.2 Accounting for DIF and Mean Differences in Delinquency.

Moderated nonlinear factor analyses (MNLFA) were subsequently fit to better understand the nature of any DIF that was observed. MNLFA is a flexible method for examining DIF that enables the use of continuous predictors of DIF, and the simultaneous inclusion of multiple predictors of DIF (Bauer, 2017; Curran et al., 2014). That is, the MNLFA makes it possible to both consider DIF across more continuous dimensions like income, and the extent to which one variable (e.g., race) is associated with DIF after controlling other variables (e.g., income).

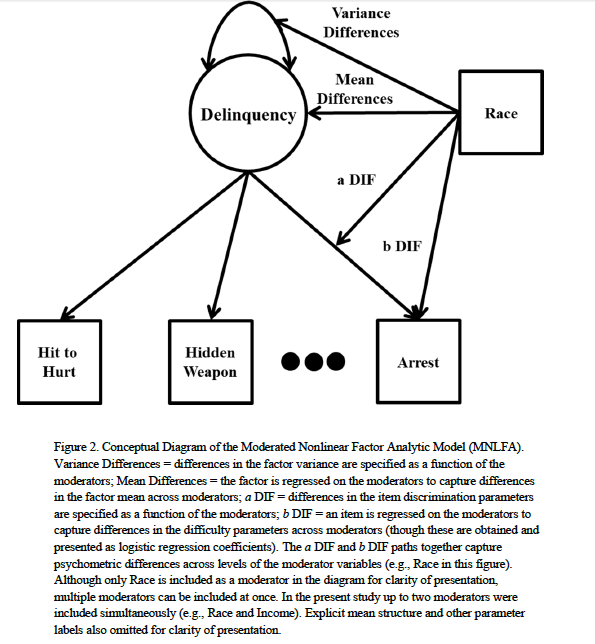

A conceptual diagram of the MNLFA is presented in Figure 2. In this figure, only a single item is being moderated (i.e., tested for DIF). The specification of this model began with a single group 2PL item response model being fit to the BPM item data that included White and Black youth. Differences in the factor mean and variance were then specified by adding regression paths from the moderator variables to the factor mean (Mean Differences in Figure 2), and by specifying a log-linear moderation function (to avoid impermissible implied values) for the factor variance (Variance Differences in Figure 2). Discrimination values (i.e., factor loadings) are then specified as a linear function of the moderators (a DIF in Figure 2), capturing DIF in the discrimination parameters. Finally, the items are regressed on the moderators (b DIF in Figure 2), which captures DIF in the difficulty parameters.

The first MNLFA model only included race as a moderator to provide a baseline as this re-expresses the results from the main DIF tests in the MNLFA framework. Next, we fit a series of MNLFA models where race was included along with one other moderator variable, either income, neighborhood safety, CU traits, or urgency. Given the high computational burden of MNLFA (Bauer, 2017), only items that demonstrated DIF in the main analyses were moderated in these models. Items that did not demonstrate DIF were included as un-moderated anchor items. Although the initial tests of DIF may not have detected DIF in each item parameter of the items that demonstrated DIF, we modeled DIF in both the discrimination and difficulty parameters given the exploratory nature of these models and the new moderators we examined.

2.3.3 Model Estimation.

The initial IFAs were run in Mplus version 8.5 using weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment (WLSMV) estimation (Muthen & Muthen, 2021). The 2PL item response models and DIF analyses were run in flexMIRT version 3.6 (Houts & Cai, 2020) using full information maximum likelihood estimation with the supplemented expectation maximization (SEM) algorithm (Cai, 2008). The MNLFA were also run in Mplus version 8.5 using full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. In the MNLFA, all continuous covariates were grand mean centered before being entered into the model.

Notably, some youth (36%) in this sample are siblings. In the MNLFA, cluster corrected standard errors were computed to account for the non-independence of these observations. For the initial DIF analysis, supplemental DIF tests were also conducted in which only one youth per family was randomly selected for analysis. The DIF tests presented below are based on the full sample out of concerns for power given both the low endorsement rates of the items, and the fact that more complex, multilevel item response models can substantially undermine the power to detect DIF (Jin & Kang, 2016; Jin, Myers, & Ahn, 2014). Further, the fact that most youth (64%) do not have a sibling in the sample complicates both the practical implementation and conceptual interpretation of such models (Jin et al., 2014).

3 Results

The endorsement rates for the 10 BDM items across the full sample, White youth, and Black youth are presented in Table 1. Overall endorsement rates were low with mean endorsement rates of 2.4%, 2.0%, and 4.3% for the full sample, White youth, and Black youth, respectively. The Hit to Hurt item was the most frequently endorsed with a roughly 10% endorsement rate. Endorsement rates for the other items typically ranged from less than 1% to 5%. The Steal > $5 item (endorsement rates of 0.40%, 0.20%, and 1.1% for the full sample, White youth, and Black youth) and Arrest item (endorsement rates of 0.30%, 0.10%, and 1.3% for the full sample, White youth, and Black youth) were the least frequently endorsed.

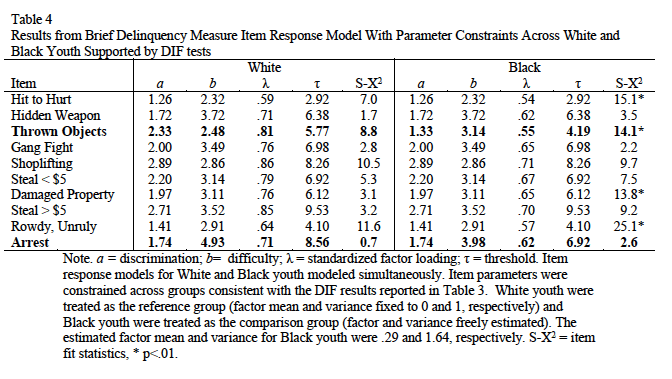

The IFAs indicated the BDM scale was essentially unidimensional. The first eigenvalues were all above 5.00, while the second eigenvalues were all around 1.00, suggesting a strong first factor (S1-4). Factor loadings on the first factors were typically large (λs from .58 to .88 in the full sample, mean λl = .72; λs from .50 to .92 for White youth, mean λ = .70; λs from .64 to .89 for Black youth, mean λ = .72). When more than one factor was extracted, there was some evidence for a small second factor centered around stealing behaviors, but factor correlations were typically large (mean factor r = .57) and in general the multi-factor solutions were not conceptually useful (S1-4).

Results from the initial, single-group 2PL item response models indicated that all items were strongly related to the latent delinquency factor (mean afull = 2.29; mean aWhite = 2.12; mean aBlack = 2.43; S5). Consistent with the endorsement frequencies, all items had high difficulty parameters (mean bfull = 2.79; mean bWhite = 3.13; mean bBlack = 2.33). The 2PL models also demonstrated good fit for White (M2 = 161.06, df = 35, p <.01) and Black youth (M2 = 90.70, df = 35, p <.01). In this preliminary step, all models were estimated separately and so parameter estimates cannot be directly compared across groups (i.e., groups must be linked in the same model for comparisons).

3.1 DIF in the Delinquency Items across White and Black Youth

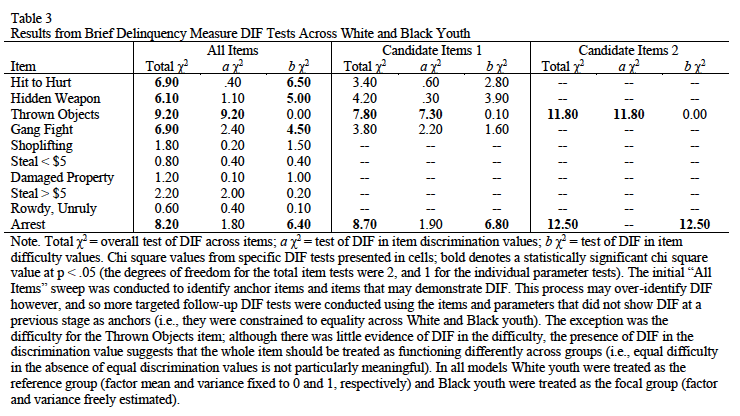

The results from the three DIF models are presented in Table 3. This table includes the Wald test statistics for the total item DIF tests (Total χ2), item discrimination value DIF tests (a χ2), and item difficulty value DIF tests (b χ 2). Degrees of freedom were either 2 (for the total item tests) or 1 (for the individual item parameter tests). In the first model where all items were tested for DIF simultaneously there was some evidence of DIF in five items: Hit to Hurt, Hidden Weapon, Thrown Objects, Gang Fight, and Arrest.

In the second DIF model, the five aforementioned items were tested for DIF while the remaining five items were used as anchors (Candidate Items 1 in Table 3). Only the Thrown Objects and Arrest items showed evidence of DIF. For the Thrown Objects item, DIF was primarily associated with the discrimination parameter, while for the Arrest item DIF was primarily associated with the difficulty parameter. In the third DIF model, only the Thrown Objects and Arrest items were tested for DIF; all other items served as anchor items (Candidate Items 2 in Table 3). The discrimination parameter for the Arrest item was also constrained across White and Black youth as there was little evidence for DIF in this parameter. Although there was also little evidence for DIF in the Thrown Objects difficulty parameter, it was still free to vary across groups as equal discriminations is typically considered a prerequisite for constraining difficulty parameters (i.e., equal difficulty parameters without equal discrimination parameters are not particularly meaningful; see Panel b in Figure 1). In this model, there was still evidence for DIF in the Thrown Objects discrimination parameter and the Arrest item difficulty parameter.

The item parameter estimates from the final DIF model (Candidate Items 2 in Table 3) for White and Black youth are presented in Table 4. This table includes both the IRT parameter estimates (i.e., discrimination and difficulty) and the corresponding estimates from non-IRT parameterized, factor analytic models (i.e., standardized factor loadings and item thresholds; Kamata & Bauer, 2008). The Thrown Objects item was more discriminating among White youth than Black youth (aWhite = 2.33; aBlack = 1.33), meaning that this item is more strongly related to delinquency for White youth. Second, the Arrest item was more difficult for White youth compared to Black youth (bWhite = 4.93; bBlack = 3.98). That is, among Black and White youth with similar levels of delinquency, Black youth were more likely to report being arrested.

The DIF in these two items increased the observed mean difference in delinquency between White and Black youth and lowered the observed variance difference between White and Black youth. When no DIF was assumed the mean difference between groups on the delinquency factor scores (generated in flexMIRT via expected a posteriori scoring) corresponded to d = 0.63, which dropped to d = 0.45 after incorporating DIF into the model (a reduction of about 25%). Regarding the factor variance, in the no DIF model, there was 2.5 times as much variance in the delinquency factor scores for Black youth compared to White youth. When DIF was modeled, there was 2.73 times as much variance in the delinquency factor scores for Black youth compared to White youth.

The results from the DIF models in the reduced sample can be found in the online supplement. In the first model where all items were tested simultaneously only the Arrest item demonstrated statistically significant DIF, though there was some evidence for a DIF in the Thrown Objects item (χ2 = 3.0; df = 1; p = .09). The second supplemental DIF model included both the Arrest and Thrown Objects items as candidate items; the Thrown Objects items was included given the results from other analyses and out of caution for potentially missing DIF as the inclusion of anchor items can increase power. Consistent with the main analyses, the Arrest item demonstrated statistically significant DIF for the b parameter (χ2 = 9.6; df = 1; p = .002), and the Thrown Objects item demonstrated statistically significant DIF for the a parameter (χ2 = 4.0; df = 1; p = .047) though this effect was smaller and less reliable. The parameter estimates from the final reduced sample BDM item response models were consistent with those in Table 4 (S7).

3.2 DIF in the Delinquency Items across White and Black Youth after accounting for Covariates

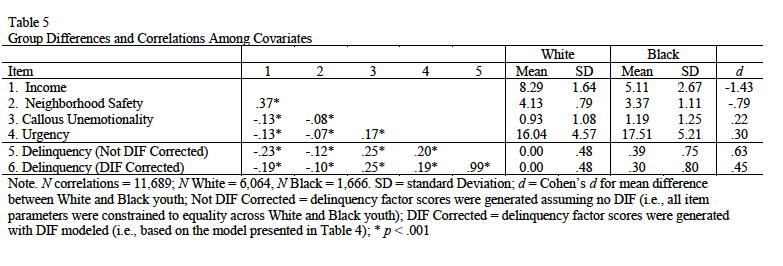

Correlations among the covariates and delinquency factor scores are presented in Table 5; descriptive statistics for White and Black youth on the covariates are also provided. The covariates exhibited small to medium intercorrelations (mean r = .16). There were large mean differences between Black and White youth for household income (d = -1.43) and neighborhood safety (d = -0.79), and smaller differences in CU traits (d = 0.22) and urgency (d = 0.30).

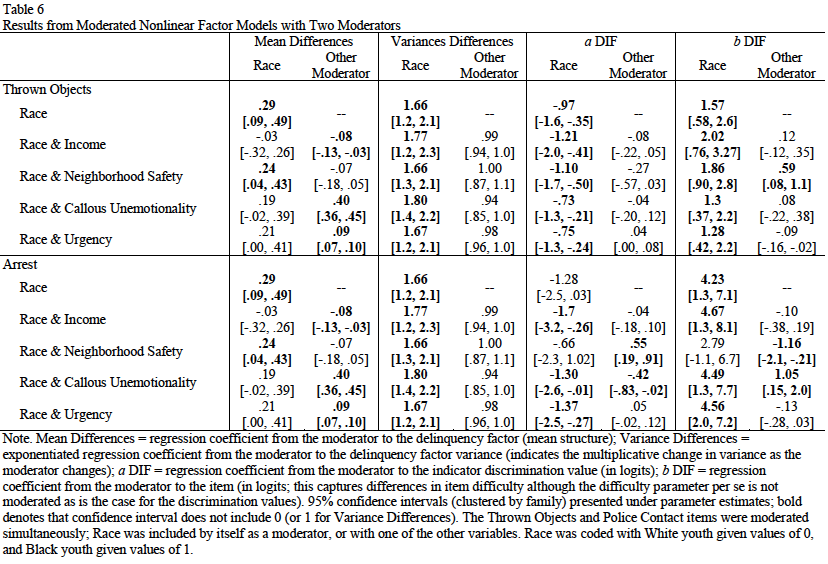

Results from the MNLFA can be found in Table 6. The columns in the table are labeled to correspond to the paths shown in Figure 2. Results from the baseline MNLFA with only race as a moderator primarily re-express the results presented in Table 4. The only difference was that the difference in difficulty values for the Thrown Objects item was statistically significant here. Across models, there was consistently more variance in delinquency for Black youth compared to White youth (on average around 1.70 times as much variance).

Inclusion of the covariates reduced the mean differences in delinquency between White and Black youth to varying degrees (from 17% to effectively 100%). This was most pronounced when household income was included in the model, which fully accounted for the mean differences between Black and White youth on the delinquency factor. Higher income was associated with lower delinquency; however, race was still associated with DIF in both items. That is, even after equating for overall delinquency and household income, Black youth were still more likely to endorse the Arrest item.

Neighborhood safety was the only covariate to have a notable effect on the magnitude of the b DIF of the Arrest item, reducing the DIF by 35% so that it was no longer statistically significant. Neighborhood safety, however, was also associated with a significant DIF effects on the a and b parameters of the Arrest item such that greater neighborhood safety was associated with higher discrimination (i.e., the Arrest item had a stronger association with delinquency in safer neighborhoods), and a lower likelihood of endorsing Arrest, holding delinquency constant.

CU traits and urgency each accounted for about 30% of the race difference on the delinquency factor, and each trait was associated with higher overall delinquency. Neither personality trait accounted for the DIF related to race for either item. CU traits, however, were associated with DIF effects on the a and b parameters of the Arrest item such that youth high in CU traits were more likely to endorse the Arrest item holding delinquency constant, but the discrimination value was lower (i.e., was less informative about delinquency) for youth with high CU traits.

4 Discussion

Early delinquent behavior is associated with a variety of negative outcomes and is therefore important to assess in emerging adolescents. However, it is critical that these assessments accurately reflect delinquency and not racially biased disciplinary practices. Thus, we examined DIF between Black and White youth on the BDM in the ABCD study, guided by an expectation that if there were bias originating in systemic discrimination on the basis of race in aspects of delinquency, an approach testing for DIF should be able to detect it. We did find DIF for two items: have you been arrested or picked up by the police other than for a minor traffic offense in the past year, and have you thrown objects such as rocks or bottles at people in the past year.

The Arrest item was identified a priori as having theoretical reasons for exhibiting DIF (i.e., known differences in policing of Black vs White youth). Consistent with our hypotheses, the Arrest item was more difficult for White youth compared to Black youth, indicating that Black youth were more likely to report police contact than White youth at the same level of delinquency. These findings complement research showing that police employ more aggressive policies (e.g., stop, question, and frisk) in communities of color, even after controlling for levels of crime and other social characteristics (Fagan & Davies, 2000; MacDonald et al., 2016). That this DIF appears in a relatively young sample (ages 10-11 years old) highlights how bias in police contact can occur at a young age. The second item that was identified a priori—the Rowdy, Unruly item—did not demonstrate any evidence of DIF in the current sample.

We did, however, find evidence that the Thrown Objects item was more discriminating among White youth than Black youth, providing more information about the delinquency of White youth compared to Black youth. This DIF was not hypothesized a priori and we lack any theoretical explanation for its presence, nor were any of the covariates able to account for the DIF associated with race on this item. Therefore, we do not consider this DIF to be particularly meaningful conceptually unless replicated in other samples, and do not speculate on this finding further. However, even if there is no theoretical explanation for DIF, overall delinquency factor scores should probably be adjusted for the DIF associated with this item.

Consistent with previous research, we found higher mean levels of self-reported delinquency in Black youth relative to White youth, even after accounting for DIF. Black youth were also disproportionately from households with lower income and lived in areas with lower neighborhood safety. So, although Black youth reported higher levels of delinquency, they were also disproportionately impacted by environmental stressors, differences that were larger than the difference between Black and White youth on delinquency. Further, income completely accounted for the mean difference in delinquency between Black and White youth, highlighting the importance of investigating these types of variables in future work that seeks to examine the etiology of antisocial behavior.

Neighborhood safety was the only covariate that accounted for a significant portion of the DIF associated with race and the Arrest item. Youth living in more dangerous neighborhoods were more likely to endorse the Arrest item (after accounting for race and overall delinquency). These results are consistent with findings that neighborhoods with higher levels of crime are often subject to increased police presence and more aggressive policing strategies (Gaston & Brunson, 2018). Notably, on average, Black and White youth do not live in the same kind of neighborhoods given how discriminatory housing, banking, and infrastructure development practices have differentially impacted Black versus White communities (Peterson & Krivo, 2010). These findings thus contradict suggestions that disproportionate police contact among Black youth is solely a function of an increased level of criminal behavior, and instead demonstrate that contact with law enforcement is linked to unsafe neighborhoods and aggressive policing practices, which disproportionately impacts Black youth.

While household income, CU traits, and urgency reduced mean differences in delinquency between Black and White youth, they had little impact on the DIF related to race on the Arrest item. CU traits and urgency are well-replicated person-level correlates of increased delinquency (Horan et al., 2015). The fact that these traits did not account for DIF on the Arrest item between Black and White youth provides additional evidence for the importance of broader contextual factors as underlying the differential likelihood of police contact.

4.1 Implications for the Assessment of Delinquency and Approaches to Examining Group Differences

While the source and relevance of the DIF detected in the Thrown Objects item is less clear and may reflect other variables not examined, clearer implications are supported for the Arrest item. The differential responses to the Arrest item across Black and White youth are consistent with biased policing practices wherein Black individuals disproportionately reside in neighborhoods with higher crime that correspondingly have a higher police presence, leading to higher rates of police contact for matched levels of delinquency.1

Accurately measuring levels of delinquency is important for understanding the development of externalizing behavior in youth and identifying those who might benefit most from early interventions. We recommend that researchers either refrain from the use of the Arrest item to measure delinquency due to DIF across Black and White youth or explicitly model the DIF when generating scores. This DIF has the potential to contribute to biased results regarding associations with criterion variables and mean-levels or patterns of correlations between groups, relative to scores adjusted for DIF. Reports of arrest still provide useful information as an outcome variable, however, for helping to understand the link between delinquency and adjustment, and to study the impact of policing on youth development. For example, it is important to understand if youth that exhibit high rates of delinquent behavior and have police contact at an early age are more likely to develop symptoms of psychopathology. Scholars have noted the dearth of quantitative studies on racial equity in policing, relying primarily on official crime and police reports instead of also collecting data from the people that are being policed (Goff & Khan, 2012). Self-reports of arrest could help researchers to answer important questions about the impact of arrest and interactions with police on the development of youth.

More generally, this work demonstrates the importance of considering psychometric bias in developmental science and using quantitative approaches to test for and explain such bias, especially when there is reason to believe measures could be impacted by systematic discrimination. The combination of the multiple sweep approach to detect DIF with follow-up analyses using MNLFA models to test hypotheses to identify the sources of DIF provides a rigorous quantitative framework by which examine group differences on numerous topics of high public health and policy importance. Integrating this quantitative approach with content-specific theoretical model to identify key covariates will be especially generative improving our ability to draw more appropriate inferences from our measures; to create valid, culturally sensitive measures; to facilitate more inclusive science; and to contribute to understanding substantive questions concerning the impact of systemic bias on key health and policy outcomes.

1 Relevant to the ABCD study, the BDM has been discontinued in future waves of data collection due to “evidence of significant race/culture bias in this measure” and redundancy with other measures (i.e., the Conduct Disorder section of the KSADS). In addition, the summary scores from previous waves of data collection are not part of the Data Release 4.0 (http://dx.doi.org/10.15154/1523041).

4.2 Limitations and Conclusions

Results should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. First, these analyses do not directly test the proposition that given Black and White youth engaging in the same behavior, Black youth are more likely to be arrested. Testing such a proposition requires an experimental design. Rather, the DIF and MNLFA analyses provide a form of statistical control that adjusts the likelihood of arrest given the context of other delinquent behaviors, and the covariates suggest other factors that influence group differences in overall delinquency and arrest. Relative to an experiment, this has the advantage of greater ecological validity, and ease in weighting the effects of multiple variables simultaneously. Indeed, this is a powerful method when interpreted in the context of other information (e.g., empirical evidence regarding bias in policing), but the ability to make causal inferences remains quite limited.

Other limitations include that the BDM is a retrospective self-report of delinquent behaviors, and therefore we are reliant on youths’ ability to remember their lifetime engagement in these behaviors and their interpretation of the items. In addition, several of the behaviors measured by the BDM occur at very low rates in the ABCD sample, which is not surprising given their young age and the fact that the sample is not a high risk one. This in turn leads to large confidence intervals in our analyses, which diminishes the reliability of the estimates and limits generalizability to ages where these items may be endorsed more frequently. Future work should extend these findings by evaluating DIF in the assessment of delinquency and antisocial behaviors in adolescents and young adults. Also, our analyses were limited to examining differences in responses between non-Hispanic Black and White youth. In addition, the items that comprise the BDM were derived from a longer, more comprehensive measure of delinquent behavior wherein DIF existed across gender, age, race/ethnicity, and place of residence for a number of items (Piquero, Macintosh, & Hickman, 2002). Also, as we were not involved in the development of the BDM, we do not have insight into the measurement model (i.e., formative, Rasch) that was used when selecting items and developing the scale (Peterson et al., 2017). Due to the low endorsement rates, however, the data of the current study were not well suited to fit more complex models that included simultaneous tests of DIF for gender, place of residence, and race/ethnicity. However, rates of delinquency are likely to increase in later adolescence, increasing the power to evaluate DIF across these other group identities.

Despite these limitations, we were able to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of DIF in the BDM in a large, diverse dataset of emerging adolescents. We found that the practical effect of DIF at this age is small to moderate (accounting for DIF reduced Black v. White differences by 25%), and that contextual factors such as neighborhood safety—not elevated urgency or CU traits—can help account for differences in police contact between Black and White youth. However, the theoretical relevance and detection of DIF for the Arrest item and accompanying covariate analysis has substantive importance, and should be a focus of continued research, especially as participants age and are more likely to have interactions with police.