Abstract

The brain has evolved to understand and interact with other people. We are increasingly learning more about the neurophysiological basis of social cognition and what is known as the social brain, that is the network of brain regions involved in understanding others. This paper focuses on how the social brain develops during adolescence. Adolescence is a time characterized by change – hormonally, physically, psychologically and socially. Yet until recently this period of life was neglected by cognitive neuroscience. In the past decade, research has shown that the brain develops both structurally and functionally during adolescence. Largescale structural MRI studies have demonstrated development during adolescence in white matter and grey matter volumes in regions within the social brain. Activity in some of these regions, as measured using fMRI, also shows changes between adolescence and adulthood during social cognition tasks. I will also present evidence that theory of mind usage is still developing late in adolescence. Finally, I will speculate on potential implications of this research for society.

Humans are exquisitely social

Humans are an exquisitely social species. We are constantly reading each other's actions, gestures and faces in terms of underlying mental states and emotions, in an attempt to figure out what other people are thinking and feeling, and what they are about to do next. This is known as theory of mind or mentalising. Developmental psychology research on theory of mind has demonstrated that the ability to understand others' mental states develops over the first four or five years of life. While certain aspects of theory of mind are present in infancy,1 it is not until around the age of four years that children begin explicitly to understand that someone else can hold a belief that differs from one's own, and which can be false.2 An understanding of others' mental states plays a critical role in social interaction because it enables us to work out what other people want and what they are about to do next, and to modify our own behaviour accordingly.

The social brain

Over the past 15 years, a large number of independent neuroimaging studies have shown remarkable consistency in identifying the brain regions that are involved in theory of mind or mentalising. These studies have employed a wide range of stimuli including stories, sentences, words, cartoons and animations, each designed to elicit the attribution of mental states (see Amodio and Frith3 for review). In each case, the mentalising task resulted in the activation of a network of regions including the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) at the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ), the temporal poles and the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; see Burnett and Blakemore.)4 The agreement between neuroimaging studies in this area is remarkable and the consistent localisation of activity within a network of regions including the pSTS/TPJ and mPFC, as well as the temporal poles, suggests that these regions are key to the process of mentalising.

Brain lesion studies have consistently demonstrated that the superior temporal lobes5 and PFC6 are involved in mentalising, as damage to these brain areas impairs mentalising abilities. Interestingly, one study reported a patient with extensive PFC damage whose mentalising abilities were intact,7 suggesting that this region is not necessary for mentalising. However, there are other explanations for this surprising and intriguing finding. It is possible that, due to plasticity, this patient used a different neural strategy in mentalising tasks. Alternatively, it is possible that damage to this area at different ages has different consequences for mentalising abilities. The patient described by Bird and colleagues7 had sustained her PFC lesion at a later age (62 years) than most previously reported patients who show impairments on mentalising tasks. Perhaps mPFC lesions later in life spare mentalising abilities, whereas damage that occurs earlier in life is detrimental. It is possible that mPFC is necessary for the acquisition of mentalising but not essential for later implementation of mentalising. Intriguingly, this is in line with recent data from developmental fMRI studies of mentalising, which suggest that the mPFC contributes differentially to mentalising at different ages.

Development of mentalising during adolescence

There is a rich literature on the development of social cognition in infancy and childhood, pointing to step-wise changes in social cognitive abilities during the first five years of life. However, there has been surprisingly little empirical research on social cognitive development beyond childhood. Only recently have studies focused on development of the social brain beyond early childhood, and these support evidence from social psychology that adolescence represents a period of significant social development. Most researchers in the field use the onset of puberty as the starting point for adolescence. The end of adolescence is harder to define and there are significant cultural variations. However, the end of the teenage years represents a working consensus in Western countries. Adolescence is characterized by psychological changes in terms of identity, self-consciousness and relationships with others. Compared with children, adolescents are more sociable, form more complex and hierarchical peer relationships, and are more sensitive to acceptance and rejection by peers.8 Although the underlying factors of these social changes are most likely to be multifaceted, one possible cause is development of the social brain.

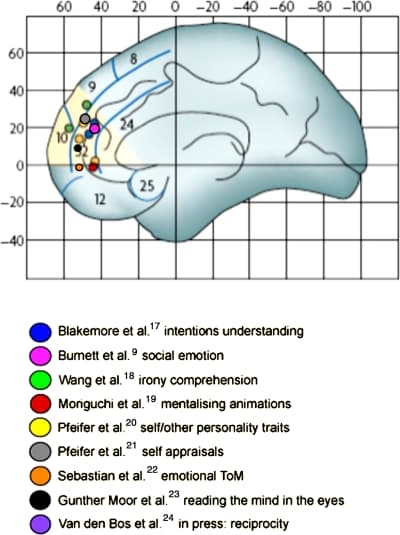

Recently, a number of fMRI studies have investigated the development during adolescence of the functional brain correlates of mentalising. These studies have used a wide variety of mentalising tasks – involving the spontaneous attribution of mental states to animated shapes, reflecting on one's intentions to carry out certain actions, thinking about the preferences and dispositions of oneself or a fictitious story character, and judging the sincerity or sarcasm of another person's communicative intentions. Despite the variety of mentalising tasks used, these studies of mental state attribution have consistently shown that mPFC cortex activity during mentalising tasks decreases between adolescence and adulthood (Figure 1). Each of these studies compared brain activity in young adolescents and adults while they were performing a task that involved thinking about mental states (see Figure 1 for details of studies). In each of these studies, mPFC activity was greater in the adolescent group than in the adult group during the mentalising task compared to the control task. In addition, there is evidence for differential functional connectivity between mPFC and other parts of the mentalising network across age.9

Figure 1 A section of the dorsal MPFC that is activated in studies of mentalising: Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) ‘y’ coordinates range from 30 to 60, and ‘z’ coordinates range from 0 to 40. Dots indicate voxels of decreasing activity during seven mentalising tasks between late childhood and adulthood.10,16 The mentalising tasks ranged from understanding irony, which requires separating the literal from the intended meaning of a comment, thinking about one's own intentions, thinking about whether character traits describe oneself or another familiar other, watching animations in which characters appear to have intentions and emotions, and thinking about social emotions such as guilt and embarrassment.9

To summarize, a number of developmental neuroimaging studies of social cognition have been carried out by different labs around the world, and there is striking consistency with respect to the direction of change in mPFC activity. It is not yet understood why mPFC activity decreases between adolescence and adulthood during mentalising tasks, but two non-mutually exclusive explanations have been put forward (see Blakemore10 for details). One possibility is that the cognitive strategy for mentalising changes between adolescence and adulthood. A second possibility is that the functional change with age is due to neuroanatomical changes that occur during this period. Decreases in activity are frequently interpreted as being due to developmental reductions in grey matter volume, presumably related to synaptic pruning. However, there is currently no direct way to test the relationship between number of synapses, synaptic activity and neural activity as measured by fMRI in humans (see Blakemore10 for discussion). If the neural substrates for social cognition change during adolescence, what are the consequences for social cognitive behaviour?

Online mentalising usage is still developing in mid-adolescence

Most developmental studies of social cognition focus on early childhood, possibly because children perform adequately in even quite complex mentalising tasks at around age four. This can be attributed to a lack of suitable paradigms: generally, in order to create a mentalising task that does not elicit ceiling performance in children aged five and older, the linguistic and executive demands of the task must be increased. This renders any age-associated improvement in performance difficult to attribute solely to improved mentalising ability. However, the protracted structural and functional development in adolescence and early adulthood of the brain regions involved in theory of mind might be expected to affect mental state understanding. In addition, evidence from social psychology studies shows substantial changes in social competence and social behaviour during adolescence, and this is hypothesized to rely on a more sophisticated manner of thinking about and relating to other people – including understanding their mental states.

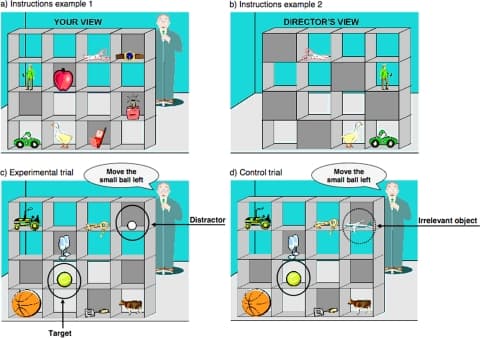

Recently, we adapted a task that requires the online use of theory of mind information when making decisions in a communication game, and which produces large numbers of errors even in adults.11 In our computerized version of the task, participants view a set of shelves containing objects, which they are instructed to move by a ‘Director’, who can see some but not all of the objects (Figure 2).12 Correct interpretation of critical instructions requires participants to use the director's perspective and only move objects that the director can see (the director condition). We tested participants aged between 7 and 27 years and found that, while performance in the director and a control condition followed the same trajectory (improved accuracy) from mid-childhood until mid-adolescence, the mid-adolescent group made more errors than the adults in the director condition only. These results suggest that the ability to take another person's perspective to direct appropriate behaviour is still undergoing development at this relatively late stage.

Figure 2 a, b. Images used to explain the Director condition: participants were shown an example of their view (a) and the corresponding director's view (b) for a typical stimulus with four objects in occluded slots that the director cannot see (e.g. the apple); c, d. Example of an experimental (c) and a control trial (d) in the Director condition. The participant hears the verbal instruction: ‘Move the small ball left’ from the director. In the experimental trial (c), if the participant ignored the director's perspective, she would choose to move the distractor ball (golf ball), which is the smallest ball in the shelves but which cannot be seen by the director, instead of the larger ball (tennis ball) shared by both the participant's and the instructor's perspective (target). In the control trial (d), an irrelevant object (plane) replaces the distractor item

Implications for society

There are many questions that remain to be investigated in this new and rapidly expanding field. The study of neural development during adolescence is likely to have important implications for society in relation to education and the legal treatment of teenagers, as well as a variety of mental illnesses that often have their onset in adolescence.13

Research into the cognitive implications of continued brain maturation beyond childhood may be relevant to the social development and educational attainment of adolescents. Further studies are necessary to reach a consensus about how brain development impacts on social, emotional, linguistic, mathematical and creative development. In other words, which skills undergo perturbation, which undergo sensitive periods for enhancement and how does the quality of the environment interact with brain changes in the development of cognition? Longitudinal studies of the effect of early deprivation on the cognitive development of Romanian adoptees in the UK have begun to investigate this question.14 Whether greater emphasis on social and emotional cognitive development would be beneficial during adolescence is unknown but research will provide insights into potential intervention schemes in secondary schools, for example, for remediation programs for antisocial behaviour.

Understanding the brain mechanisms that underlie learning and memory, and the effects of genetics, the environment, emotion and age on learning could transform educational strategies and enable us to design programs that optimize learning for people of all ages and of all needs. Neuroscience can now offer some understanding of how the brain learns new information and processes this information throughout life.15 Understanding the brain basis of social functioning and social development is crucial to the fostering of social competence inside and outside the classroom. Social functioning plays a role in shaping learning and academic performance (and vice versa), and understanding the neural basis of social behaviour can contribute to understanding the origins and process of schooling success and failure. The finding that changes in brain structure continue into adolescence (and beyond) has challenged accepted views, and has given rise to a recent spate of investigations into the way cognition (including social cognition) might change as a consequence. Research suggests that adolescence is a key time for the development of regions of the brain involved in social cognition and self-awareness. This is likely to be due to the interplay between a number of factors, including changes in the social environment and in puberty hormones, as well as structural and functional brain development and improvements in social cognition.

If early childhood is seen as a major opportunity – or a ‘sensitive period’ - for teaching, so too should the teenage years. During both periods, particularly dramatic brain reorganization is taking place. The idea that teenagers should still go to school and be educated is relatively new. And yet the research on brain development suggests that education during the teenage years is vital. The brain is still developing during this period, is adaptable, and needs to be moulded and shaped. Perhaps the aims of education for adolescents might change to include abilities that are controlled by the parts of the brain that undergo most change during adolescence. These abilities include internal control, multi-tasking and planning – but also self-awareness and social cognitive skills such as perspective taking and the understanding of other people's minds.

Conclusion

The study of brain development beyond childhood is a new but rapidly evolving field with applications for education and social policy. The finding that changes in brain structure and function continue into adolescence has challenged accepted views. In this paper, I have focused on research in developmental cognitive neuroscience, but a richer account of changes in adolescent learning, strategic and social behaviour requires a multidisciplinary approach that recognizes the complex interactions between genetics, brain structure, physiology and chemistry, and the environment.