Abstract

Theories of judgment in decision making hypothesize that throughout adolescence, judgment is impaired because the development of several psychosocial factors that are presumed to influence decision making lags behind the development of the cognitive capacities that are required to make mature decisions. This study uses an innovative video technique to examine the role of several psychosocial factors—temporal perspective, peer influence, and risk perception—in adolescent criminal decision making. Results based on data collected from 56 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 18 years revealed that detained youth were more likely to think of future-oriented consequences of engaging in the depicted delinquent act and less likely to anticipate pressure from their friends than nondetained youth. Examination of the developmental functions of the psychosocial factors indicates age-based differences on standardized measures of temporal perspective and resistance to peer influence and on measures of the role of risk perception in criminal decision making. Assessments of criminal responsibility and culpability were predicted by age and ethnicity. Implications for punishment in the juvenile justice system are discussed.

BACKGROUND

In 2000, adolescents who are charged with crimes face a very different juvenile justice system than the one that was envisioned when the juvenile court was founded in 1899. The juvenile court, which was intended to evaluate the needs of each youth in an effort to rehabilitate him or her, has become increasingly punitive (Reppucci, 1999). The 1980s and 1990s were characterized by increasingly adult-like treatment of juveniles in the court system and increased focus on the protection of the community rather than the protection of the juvenile defendant. Between 1992 and 1995, 41 states enacted laws making it easier to prosecute juveniles in adult criminal court (Sickmund, Snyder, & Poe-Yamagata, 1997). Other legislative mechanisms that emphasize punishment over rehabilitation of juveniles include minimum sentencing requirements, blended sentencing that allows juveniles to be sentenced past the age of 21 years, and revision of confidentiality provisions in favor of more open proceedings and records.

One of the premises for the establishment of the juvenile court and for the special treatment traditionally afforded to youthful offenders is that juveniles are less mature and thus less responsible for the crimes they commit. A criminal justice system that uses age and developmental maturity as mitigating factors in determining criminal responsibility is concordant with the rationale used in several Supreme Court decisions (e.g., Parham v. J.R. , 1979). If developmental immaturity is linked to poor decision making in criminal situations, then age would presumably be a crucial mitigating factor in the assignment of blame and punishment.

Adolescent decision making has been studied in several legally relevant contexts, including competence to make abortion decisions (Ambuel & Rappaport, 1992), consent to medical treatment(Weithorn, 1982), and waiver of Miranda rights (Grisso, 1981).The standard of informed consent was used to evaluate adolescent competence in these studies. Under the informed-consent model, the law deems that an individual is competent to make a decision if he or she is capable of making a knowing, voluntary, and intelligent decision. In general, these studies have found that, past the age of 14 years, adolescents are competent decision makers under the informed-consent model (Ambuel & Rappaport, 1992; Weithorn, 1982) as long as they are of average or above-average intelligence (Grisso, 1981).

Some researchers have theorized that the informed-consent model is inadequate because it overemphasizes the cognitive components and minimizes the noncognitive factors that may influence mature judgment and decision making (Scott, Reppucci,& Woolard, 1995; Steinberg & Cauffman, 1996). Scott and associates (1995) proposed a judgment model that incorporates peer and parental compliance and conformity, attitude toward and perception of risk, and temporal perspective into the informed consent model. Steinberg and Cauffman (1996) argued that psychosocial immaturity in the areas of responsibility, temperance, and perspective should be considered in evaluating the decision-making capabilities of adolescents. Both groups of authors have suggested that developmental differences in these psychosocial factors may influence adolescents to make poor judgments in some contexts. Their arguments rest on the following findings from developmental psychology: (a) adolescents are more subject to direct peer pressure and desire for peer approval than are young adults (Berndt, 1979), (b) adolescents are more likely to see themselves as invulnerable to risks (Elkind, 1967) and more likely to weigh more heavily the negative consequences of not engaging in risky behaviors than are adults (Beyth-Marom, Austin, Fishhoff, Palmgren,&Quadrel, 1992), (c) adolescents have a greater tendency than adults to discount the future and weigh short-term consequences more heavily than long-term consequences (Gardner&Herman, 1991), and (d) temporal perspective continues to develop throughout adolescence and into early adulthood (Nurmi, 1991).

While adolescent decision making has been studied in at least a few legal criminal contexts, such as understanding of Miranda warnings (Grisso, 1981) and competence to stand trial (Woolard, 1998), it has not been studied in relation to decisions that lead to criminal activity. This line of research seems especially relevant in light of the current changes in the juvenile justice system. In order for a youth to be considered culpable and punished in juvenile court, it must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the juvenile actually formed criminal intent, which requires that the youth be able to consider the consequences of a particular act and think sequentially about abstract possibilities (Weithorn, 1982).

The present study attempts to evaluate the influence of several psychosocial factors—temporal perspective, peer influence, and risk perception—in criminal decision making by asking adolescents to imagine that they are participants in a fictitious video vignette portraying an incident in which poor judgment ultimately results in a crime with grave consequences. Analyses are intended to evaluate the influence of demographic characteristics and psychosocial maturity on adolescent judgment in decision making and assessments of criminal responsibility and culpability. Criminal responsibility refers to the extent to which an individual is responsible for his/her criminal behavior, while culpability refers to the extent to which an individual should be punished for his/her criminal behavior (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000).

METHOD

Participants

that works with delinquent youth, and a juvenile detention center. The final sample included 56 adolescents (73.2% male, 26.8% female) between the ages of 13 and 18 years (M D 15: 55 years; SD D 1: 57). Nearly two thirds of the youth were in detention at the time of the interview (60.7%). Among the youth who were not in detention, 57.1% had had prior contact with the juvenile justice system, so that a total of 83.6% of the sample had some contact with the juvenile justice system. Whites (37.5%) and African Americans (39.3%) were equally represented in the study, with the remaining 23.2% indicating they were either of Hispanic, Asian, or biracial descent. Minorities were overrepresented among juveniles in detention, accounting for 76.5% of detainees and 40.9% of the nondetained sample. There were no significant differences by age or socioeconomic status between detained and nondetained youth. Nor were there age differences between males and females. There were also no significant differences between the cognitive functioning percentile rankings for detained and nondetained adolescents.

Procedure

After providing informed consent, 103 participants were screened to determine whether they had seen the movie Sleepers . There were no significant differences on the demographic variables between the adolescents who had seen Sleepers and those who had not.The 56 adolescents who had not seen the movie participated in the study.

In small groups of 5–15, participants watched a 5-min clip from the movie Sleepers depicting a scene in which four boys make a series of decisions beginning with a plan to steal hot dogs from a vendor and ultimately resulting in the presumed death of a man. The scene was edited into four segments. After each segment, the participants individually answered a series of written questions in which they were asked to imagine themselves in the depicted situation. The questions following the first three segments focused on several aspects of decision making, including perceived risks and benefits, possible consequences, and the role of peer influence. The questions after the final segment focused on perceptions of the boys’ criminal responsibility and culpability. After completing the video vignette segment of the study, each participant completed standardized measures of temporal perspective, resistance to peer influence, and risk perception.

Measures

Criminal Decision Making Questionnaire (CDMQ)

The CDMQ was designed for this study to evaluate the decision-making processes of adolescents. At each decision-making point in the video clip, participants were asked to answer a series of questions related to future consequences (e.g.,“What are some of the possible things that might happen in this situation?”), risk perception (e.g., “How likely do you think it is that you and your friends would get caught by the police?”), and peer influence (e.g., “How likely do you think it is that your friends would make fun of you if you tried to walk away?”). At the end of the video vignette, there were several questions regarding criminal responsibility (e.g., “Do you think you and your friends should have been able to anticipate that someone might have been badly hurt or killed at any point in this situation?”) and culpability (e.g., “Assuming this was your first offense, what punishment do you think you and your friends would get from the juvenile court judge?”).

Codes were created for each of the open-ended questions of the CDMQ. Two coders independently coded each question (92% agreement) and discrepancies were resolved by a third party. After classifying all of the consequence responses into content categories, all of the consequences were categorized as either risks or benefits (see Appendix A). The risks were then subdivided into short-term and long-term risks. The coding scheme is based on that used by Grisso (1981) in his study of juvenile competence to waive Miranda rights.

In the CDMQ, future time perspective was measured by summing the total number of long-term consequences that each respondent mentioned. The role of peer influence in decision making in criminal situations was assessed by averaging scores of the expected likelihood of certain pressuring tactics peers might employ if the respondent tried to walk away from the situation (see Appendix B) and the perceived possibility of walking away from the situation. Measures of risk perception involved two components, general risk assessment and risk preference. The average of the expected likelihood of certain risks (see Appendix B) was used as an index of general risk assessment. Risk preference was measured by calculating the proportion of benefits mentioned as compared with the number of risks mentioned and by asking adolescents how likely they would be to participate in a situation like the one depicted in the Sleepers scene.

An examination of the correlations between the CDMQ scales and the corresponding standardized psychosocial scale provides some indication of the internal validity of theCDMQ. However, we did not anticipate high correlations between the scales because the CDMQ was designed to measure the application of the psychosocial factor in a criminal context and is not intended to simply be another method of measuring the psychosocial factors. The CDMQ measure of risk assessment and the standardized measure of risk assessment were significantly correlated (r D : 44, p < : 003), as was one of the CDMQ indices of risk preference (the participants propensity to get involved) and the standardized measure of risk preference (r D : 36, p < : 01). A significant correlation also existed between one of the CDMQ measures of peer influence (the possibility of walking away from the situation) and the standardized measure of resistance to peer influence (r D : 27, p < : 05). However, the anticipation of peer influence items in the CDMQ did not correlate substantially with the standardized measure, nor did the benefit/risk ratio correlate significantly with the risk preference measure. The standardized measure of temporal perspective did not correlate with any corresponding scale in the CDMQ.

Stanford Time Perspective Inventory

Temporal perspective was measured by using the 15-item future subscale of the Stanford Time Perspective Inventory (Zimbardo, 1990). This measure documents the inclination of an individual to attend to long-range consequences (e.g., “When I want to achieve something, I set goals and consider specific means for reaching those goals.”). For the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha D : 69.

Berndt’s (1979) Vignettes of Peer Influence

This measure of susceptibility to antisocial peer pressure, which includes five short hypothetical vignettes, was used to measure resistance to peer influence. The situations described in the Berndt vignettes include shoplifting, cheating on an exam, buying a fake ID, having an unsupervised party, and taking someone’s car for a ride. Respondents report on the likelihood that they would engage in the activity based on a 4-point scale. In a sample of over 9,000 high school students, Cronbach’s alpha was .75, and was .74 for the present sample.

Benthin, Slovic, and Severson’s (1993) Scale of Risk Perception

Participants were asked to evaluate six risky behaviors (e.g., smoking cigarettes, stealing) on the extent to which each is perceived as dangerous (risk assessment) and the degree to which the benefits of participation in the activity outweigh the risks (risk preference). Cronbach’s alpha for the risk assessment items was .89, and for the risk preference items was .76.

Cognitive Functioning and Socioeconomic Status

For the detained sample, individual administrations of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990) were conducted. The K-BIT is comprised of vocabulary and matrices subscales, representing verbal and performance abilities, respectively. The average percentile ranking of the detained sample for the verbal subscale of the K-BIT was 48.56 (SD D 30: 78) and for the matrices subscale was 46.26 (SD D 28: 38). In the nondetained sample, standardized test scores from statewide tests were used as a proxy for IQ. Among the nondetained adolescents, the average vocabulary percentile ranking was 53.11 (SD D 28: 38) and the average math ranking was 35.78 (SD D 31: 35). Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured using the occupation factor of the Two Factor Index of Social Position (Hollingshead, 1957). Participants were asked to report their parents’ occupations. The mean SES score was 4.24 (SD D 1: 39), which is indicative of a middle to working class sample.

Statistical Analysis

The first stage of the analyses examined how accurately gender and detention status predicted the four psychosocial variables—temporal perspective, resistance to peer influence, risk assessment and risk preference. Ethnicity was not included in the multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) because prior research indicates, and an examination of mean differences in this sample confirms, that there are no differences between ethnic groups on measures of psychosocial maturity (Cauffman & Steinberg, in press). Due to the number of missing data points on measures of SES and cognitive functioning, these variables were not included in the MANOVA. However, the correlations between SES, cognitive functioning, and the psychosocial variables were examined.

The second stage of analyses determined which demographic characteristics predicted scores on the psychosocial variables and performance on the CDMQ. Blocks of predictors were sequentially entered into regression equations to predict each of the standardized psychosocial variables and judgment factors measured by the CDMQ. The first block of predictors included gender and detention status, followed by the linear and quadratic components of age. There was no relationship between minority status and any of the psychosocial measures or scales in the CDMQ, so minority status was not included in the regression equations.

The third stage of analyses focused on assessments of criminal responsibility and culpability. Again, blocks of predictors were sequentially entered into linear regression equations to predict each outcome variable. The first block included only gender and detention status, followed by minority status, the linear and quadratic components of age, and a block of the four standardized psychosocial measures. (Minority status was included because we had no a priori assumption that it would not be associated with assessments of criminal responsibility and culpability). Binary logistic regression was used to determine the association between punishment categories (1 D 1 year or less in jail or detention, 2 D more than 1 year in jail or detention) and the predictor variables (gender, detention status, minority status, age, and the four psychosocial factors).

RESULTS

Standardized Psychosocial Measures

An examination of the correlations between the psychosocial scales and SES and cognitive functioning indicated that risk assessment is negatively correlated with both verbal (r D ¡: 43, p < : 01) and matrix/math (r D ¡: 48, p < : 01) percentile rankings. Adolescents with lower cognitive functioning perceived activities to be more dangerous than adolescents with higher cognitive functioning. This relationship held even when the nondetained sample was removed, which was done to ensure that the association was not due to the different methods used to measure IQ in the two samples. There was no association between SES and any of the psychosocial factors. MANOVA results revealed that none of the psychosocial factors were significantly predicted by the combination of the demographic characteristics. Nor were there any significant interactions between gender and detention status in the prediction of the psychosocial factors.

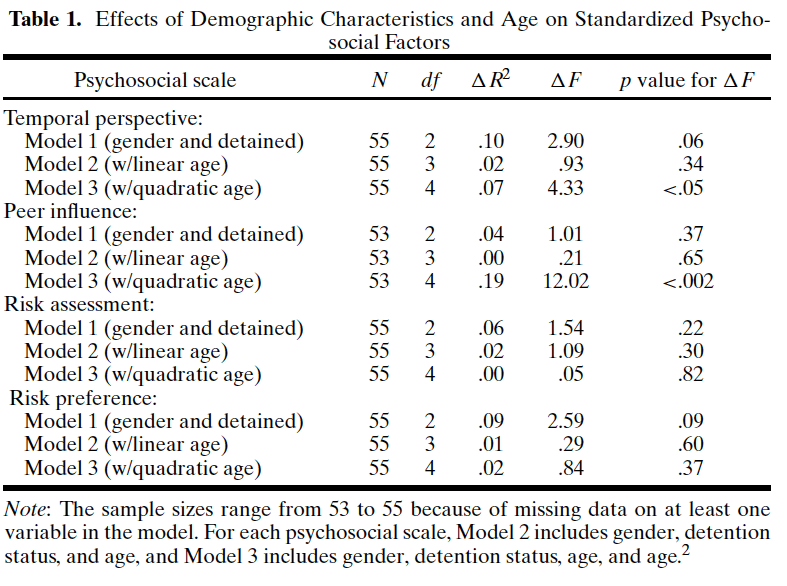

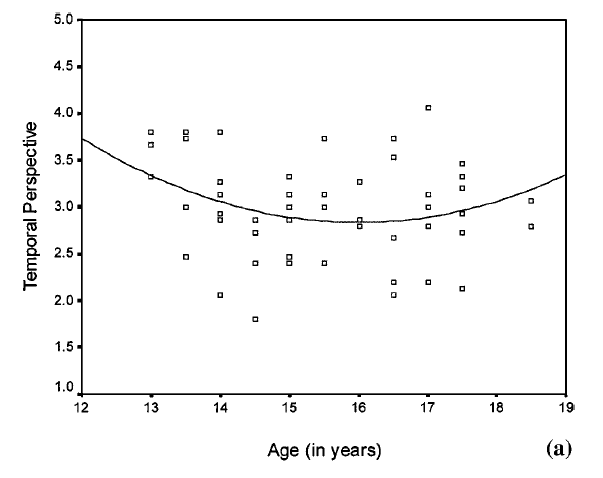

The next set of analyses focused on the developmental functions for each psychosocial variable. Table 1 provides a summary of the results for the stepwise regression equations for each psychosocial characteristic. Adding the linear component of age did not result in a significant improvement over the models that included only gender and detention status for any of the psychosocial factors. However, when the quadratic component was added, the prediction of temporal perspective, 1R2 D : 07, 1F (1, 51) D 4: 33, p < : 05, and resistance to peer influence 1R2 D : 19, 1F (1, 49) D 12: 02, p < : 002, were substantially improved. In both cases, the developmental function was U-shaped, with the youngest adolescents appearing most similar to the oldest adolescents (Fig. 1). Adolescents in the middle of the age range (15–16 years) indicated the lowest levels of future time orientation and resistance to peer influence.

Criminal Judgment Factors: CDMQ Results

An initial MANOVA of the CDMQ scales using gender and detention status revealed that of the four judgment factors, two were significantly predicted by gender and detention status—future orientation, F (3, 40) D 6: 20, p < : 002, and anticipation of peer influence, F (3, 40) D 3: 55, p < : 03. Follow-up analyses indicated that adolescents who were in detention at the time of the interview mentioned more future consequences (M D 2: 09, SD D 1: 44) and indicated they would be less likely to anticipate peer pressure in the Sleepers scenario (M D 1: 69, SD D : 65) than nondetained adolescents (number of future consequences, M D 1: 23, SD D 1: 34; anticipation of peer pressure, M D 2: 09, SD D : 70). In addition, females were more likely to anticipate pressure from their friends (M D 2: 11, SD D : 72) and mentioned fewer benefits of participation in proportion to risks (M D : 26, SD D : 15) than did their male peers (anticipation of peer pressure, M D 1: 75, SD D : 66; benefit/risk ratio, M D : 34, SD D : 20). There were no significant interactions between gender and detention status.

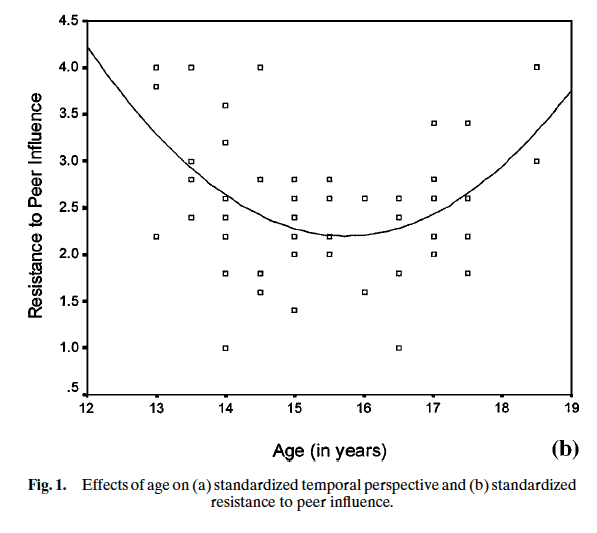

The next set of analyses focused on the developmental functions for each of the judgment factors.Table 2 provides a summary of the regression results for theCDMQ temporal perspective, peer influence, risk assessment, and risk preference judgment factors. Adding the linear component of age resulted in a significant improvement over the models that included only gender and detention status for the CDMQ measures of risk preference: for benefit/risk ratio,1R2 D : 12,1F (1, 51) D 7: 69, p < : 009, and for propensity to get involved, 1R2 D : 07, 1F (1, 51) D 3: 90, p D : 05; whereas adding the quadratic age component improved the prediction of risk assessment, 1R2 D : 11,1F (1, 43) D 5: 97, p < : 02. Older adolescents were able to generate more benefits in proportion to risks than were younger adolescents. The effects of age on risk assessment in criminal decision making are illustrated in Fig. 2. The scatterplot demonstrates that the youngest and oldest adolescents evaluated risks as more likely to occur than did middle adolescents (ages 15–16 years).

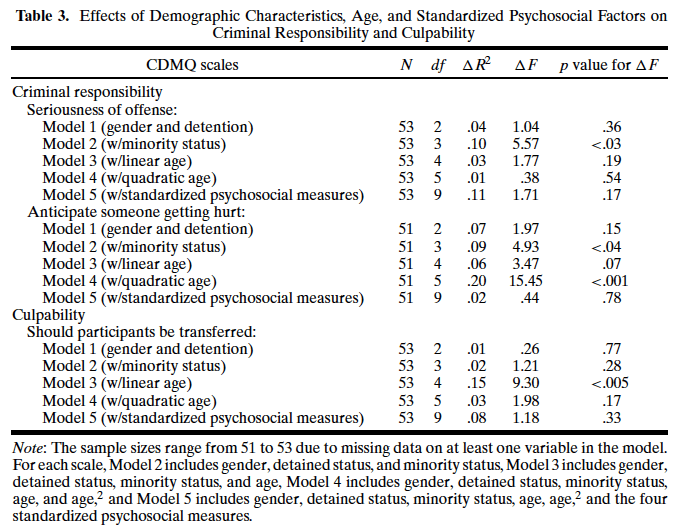

Criminal Responsibility and Culpability

Criminal responsibility was measured by perceptions of the seriousness of the offense and whether respondents thought they should have been able to anticipate that someone might get hurt. By the end of the scene, most adolescents thought the offense was very serious (on a 5-point scale, M D 4: 54, SD D 1: 01), and thought that “maybe” they should have been able to anticipate that someone might get hurt (on a 5-point scale, M D 2: 89, SD D 1: 34). See Table 3 for a summary of results from the regression models used to evaluate the effects of the demographic variables and the standardized measures of the psychosocial factors on assessments of criminal responsibility. Neither gender nor detention status was a significant predictor of either measure of criminal responsibility. However, adding information about the ethnicity of the respondent substantially improved the prediction of assessments of criminal responsibility. Minority adolescents evaluated the crime as less serious (M D 4: 31,SD D 1: 21) thanWhite adolescents (M D 4: 90,SD D : 30). Minority adolescents M D 2: 57, SD D 1: 38) were also less likely thanWhite adolescents (M D 3: 47, SD D 1: 09) to think that someone should have been able to anticipate that someone would get badly hurt. While the linear component of age did not improve the prediction of either measure of criminal responsibility, adding the quadratic age component made a substantial improvement in predicting whether a respondent thought that the youth should have been able to anticipate that someone might get hurt, 1R2 D : 21, 1F D 14: 06, p < : 001. The youngest and oldest adolescents were more likely than adolescents in the middle of the age range (15–16 years) to think that the youth should have been able to anticipate that someone might get hurt. The addition of the scores on the standardized measures of the psychosocial variables did not improve the prediction of either measure of criminal responsibility.

Whether or not an adolescent thought the youth should be transferred to adult criminal court and the anticipated punishment they would receive in both juvenile and adult criminal court were the measures of culpability in the CDMQ. Neither gender, detention, nor minority status was predictive of transfer assessments (see Table 3). However, when age was included in the prediction equation, there was a substantial improvement in the fit of the model, 1R2 D : 15, 1F (1, 49) D 9: 30, p < : 005, with younger adolescents more likely to think the youths should be transferred. Neither the quadratic component of age nor the addition of the standardized psychosocial characteristics was predictive of assessments of transfer.

Stepwise binary logistic regression was used to predict expected punishment categories. Respondents who expected less harsh punishment than confinement (e.g., community service, probation) were classified with the more lenient group. Those adolescents who expected time in jail or detention, but did not specify a length of confinement, were not included in the analyses. For expected punishment in juvenile court, gender, detention status, and age (linear and quadratic) were not significant predictors of expected punishment (Models 1, 3 and 4, Table 4). Knowing whether a respondent was a member of a minority group made a substantial contribution to the prediction of expected punishment in juvenile court, N D 29, 1Â2 D 4: 87, p < : 03 (Model 2, Table 4). Among White adolescents, 70% expected the boys to receive a sentence of 1 year or more in jail or detention from a juvenile court judge, compared with 50% of minority adolescents. When the scores on the standardized psychosocial measures were added, there was a slight additional improvement in the prediction of punishment in juvenile court, N D 29, 1Â2 D 8: 99, p D : 06 (Model 5, Table 4). Follow-up analyses demonstrated that adolescents who expected harsher punishment had higher risk assessment scores (N D 17, M D 3: 09, SD D 1: 84) than adolescents who expected more lenient punishment (N D 13, M D 2: 42, SD D 1: 28).

For adult criminal court, examination of the first two models revealed that neither gender, detention, nor minority status predicted expected punishment. When linear age effects were added to the model, there was an additional improvement in the fit of the model, 1Â2 D 4: 41, p < : 04, with younger adolescents anticipating shorter sentences. The mean age of adolescents who thought the youths would get less than a year in detention or jail was 15.44 years (SD D 1: 56), compared with a mean age of 16.38 years (SD D 1: 30) for the adolescents who thought the youths would be sentenced to more than 1 year. (See Table 4 for a summary of stepwise binomial regression results for expected punishment in juvenile and adult court.)

DISCUSSION

The results suggest that there are some age-based effects on both the standardized measures of the psychosocial factors and the CDMQ measures of judgment. Although there were linear age effects only for the CDMQ measure of risk preference, there were quadratic age effects for the standardized measures of temporal perspective and susceptibility to peer influence and for the CDMQ measure of risk assessment and one of the measures of criminal responsibility. For these characteristics, development seems to appear as a U-shaped function, with adolescents at the youngest and oldest ends of the age continuum indicating more mature levels of development than those in the middle of the continuum. This U-shaped function has been found in other studies of decision making and psychosocial maturity (e.g.,Woolard, 1998; Cauffman&Steinberg, 1997), and roughly corresponds with the age at which there is a sharp increase in the frequency of engaging in delinquent acts (Moffitt, 1993). There are at least two plausible explanations for this finding. The first is that younger adolescents are imitating parents and other adult role models, without actually having truly developed levels of maturity on some psychosocial factors (Woolard, 1998). The second is that during middle adolescence (around the ages of 15–16 years), youth experience a phase characterized by endorsement of less mature responses on some psychosocial measures, such as temporal perspective and resistance to peer influence.

Perceptions of criminal responsibility and culpability were most consistently related to minority status. Although all youth considered the offense to be very serious, minority youth generally thought the offense was less serious and the boys were less responsible. This may be related to the fact that minority youth were less likely than White youth to think that the boys should have been able to anticipate the consequences of the act and therefore saw the boys as less responsible. Consistent with the findings on criminal responsibility, minority youth thought that the boys would receive more lenient punishment from the juvenile court judge than did White youth. It is logical that if the boys were seen to be less responsible for the outcome of their behavior, they would be less deserving of punishment. Although there was not a difference in SES between minority and White youth in this sample, minority youth are more likely to grow up in poorer neighborhoods that are characterized by higher rates of criminal activity (Short, 1997). It may be that minority youth may have a reduced sense that criminal behavior is wrong because of more exposure to serious criminal activity that occurs in the environments in which they so frequently grow up (Fagan, 1999; Fagan &Wilkinson, 1998).

Age was also related to perceptions of culpability. Younger adolescents were more likely to think that they would be punished more harshly in adult criminal court and more likely to think they should be transferred to adult criminal court. The positive linear developmental trend toward thinking the youths were less deserving of harsh punishment (transfer to adult criminal court) and expecting less harsh punishment is noteworthy. It is possible that as adolescents mature, they are better able to equate punishment with criminal responsibility and see immaturity as a mitigating factor in the assignment of punishment.

The conclusions that can be drawn from this study are limited by the relatively small sample size. A larger sample that would include more females and more adolescents at the youngest and oldest ends of the age spectrum would provide more power to detect differences between the groups. However, the provocative results obtained even with a small sample suggest the importance of this line of research and should provide fodder for future investigations. An additional limitation is the lack of an adult comparison group, which prohibits us from comparing the manner in which the psychosocial factors affect decision making in adolescence versus adulthood. In order to make policy-relevant decisions, it would be necessary to evaluate the judgment model in young adults. However, the age of the youth in the video prohibited inclusion of an adult sample. The ecological validity would be severely compromised by asking adults to imagine themselves in a scene in which the participants are portrayed by 13- to 15-year-olds. A related concern was the appropriateness of asking females, members of diverse ethnic/racial groups, and adolescents from rural communities to put themselves in the place of White, urban-dwelling males. Future research could employ technology (e.g., CD-rom video) that would allow for more diversity in the situations and portrayed participants.

This study is also limited by the cross-sectional design and group administration, which was necessary to ensure that the results would not be contaminated if participants tested early were to describe the clip to future participants. Finally, the vignette measure did not adequately capture all of the psychosocial variables that were hypothesized to influence decision making. It is plausible that either the psychosocial factors were not related to decision making in criminal contexts or that the measures were not sensitive enough to capture them. Despite the limitations of this research, we feel the information gleaned supports the importance of developing sophisticated research projects to understand the relationship between developmental maturity and the culpability of youth.

CONCLUSIONS

Although culpability is one of the key issues facing the juvenile justice system, it is an elusive concept that has not received the empirical attention it deserves. With the exception of a study of psychosocial maturity among adolescents in the juvenile justice system (Cauffman & Steinberg, in press), there have been no other attempts to study juvenile culpability directly. Results from this study suggest modest support for the hypothesis that there may be some developmental differences in both the factors that are presumed to influence decision making and the exercise of judgment in criminal situations. However, larger samples of both adolescents and adults and better instruments to measure culpability and the psychosocial factors in specific legal contexts are needed. We hope this study will serve as an impetus to the development of more extensive research in this area.

If adolescents have less developed decision-making capabilities, then the rationale for a juvenile justice system that holds adolescents to adult-like standards of criminal responsibility and culpability is challenged. As suggested by Feld (1999), it may be reasonable to consider age as a mitigating factor in all criminal situations. However, there could be additional implications for the sentencing of juveniles if poorer judgment in decision making is a phase common to 15- and 16-year olds. If we can expect judgment to improve in late adolescence, then we should be wary of policies that require long sentences for adolescent offenders. In addition, our finding of differences in perceptions of criminal responsibility between minority and White adolescents might help to explain the overrepresentation of minority adolescents in the juvenile justice system. First, a lower perception of criminal responsibility might make it more likely that an individual would commit a crime, but, more importantly, it could account for racial differences in expressions of remorse. If individuals do not believe that they had control over their behavior or that their offense was not very serious, they would probably be less likely to show remorse, and therefore more likely to be seen as having a low potential for rehabilitation and receive a harsher sentence. Further investigation of this issue could provide helpful information to judges and policy makers and lead to more equitable sentencing.