Abstract

Background: Standard public health approaches to risk communication do not address the gendered dynamics of drug use. The aim of this study was to explore perceptions of fentanyl-related risks among women and men to inform future risk communication approaches. Methods: We conducted a qualitative study, purposively sampling English-speaking women and men, aged 18–25 or 35+ years, with past 12-month illicitly manufactured fentanyl use. In-depth individual interviews explored experiences of women and men related to overdose and fentanyl use. We conducted a grounded content analysis examining specific codes related to overdose and other health or social risks attributed to drug use. Using a constant comparison technique, we explored commonalities and differences in themes between women and men. Results: The study enrolled twenty-one participants, 10 women and 11 men. All participants had personal overdose experiences. Both women and men described overdosing as a “chronic” condition and expressed de-sensitization to the risk of overdose. Women and men described other risks around health, safety, and state services that often superseded their fear of overdose. Women feared physical and sexual violence and prioritized caring for children and maintaining relations with child protective services, while men feared violence arising from obtaining and using street drugs and incarceration. Only women reported that fear of violence prevented their utilization of harm reduction services. Conclusions: Experiences with overdose and risk communication among people who use fentanyl-containing opioids varied by gender. The development of gender-responsive programs that address targeted concerns may be an avenue to enhance engagement with harm reduction and treatment services and create safe spaces for women not currently accessing available services.

1. Introduction

Opioid-related deaths have continued to rise since the early 2000s in the United States (US), initially driven by prescription opioids, then heroin, and most recently illicitly manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogues (herein referred to as “fentanyl”) (Gladden, Martinez, & Seth, 2016; Rudd, Seth, David, & Scholl, 2016; Somerville et al., 2017). In Massachusetts, the number of opioid-related overdose deaths more than doubled from 911 in 2013 to more than 2,000 in each year from 2016 to 2019. This increase was driven by wide spread fentanyl adulteration of illicit drugs and replacement of the heroin supply (Ciccarone, 2017), which surged from being present in 32% of overdose fatalities in 2013–14 to in more than 90% in 2019 (Data Brief: Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths Among Massachusetts Residents, 2017; Gladden et al., 2016; MDPH, 2020; Rudd et al., 2016; Somerville et al., 2017). The opioid epidemic has often been characterized as a “white men’s health crisis” in U.S. media, (Shihipar, 2019) despite evidence that overdoses are increasing among women and people from racialized communities (Collins, Bardwell, McNeil, & Boyd, 2019; Evans et al., 2015; Gladden et al., 2016). One national U.S. study found that over half of people who initiate heroin are women (Cicero, Ellis, Surratt, & Kurtz, 2014), and the CDC reported a relative increase of 29% in overdose deaths among women between 1999 and 2018 (Hedegaard, Miniño, & Warner, 2020).

Gendered individual, interpersonal, community, and structural factors drive differences in opioid use, treatment, and harms between women and men (Bungay, Johnson, Varcoe, & Boyd, 2010; Epele, 2002; Meyer, Isaacs, El-Shahawy, Burlew, & Wechsberg, 2019). For example, more men use nonprescribed opioids and women increase their rate of use more rapidly compared to men after initiation (Des Jarlais, Feelemyer, Modi, Arasteh, & Hagan, 2012; S. F. Greenfield et al., 2007). Men are more likely to experience severe withdrawal and use multiple substances (Back et al., 2011). Women experience higher rates of injection related infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), driven by community and structural factors such as the male controlled street culture and criminalization of the sex trade that impacts women’s sexual and injection related risks (Bungay et al., 2010; Des Jarlais et al., 2012; Epele, 2002; Park et al., 2019). Gender also impacts opioid use disorder treatment responses. Family responsibilities and economic freedoms may limit women from obtaining treatment, or engaging in treatment that requires daily visits (Ait-Daoud et al., 2019; Meyer et al., 2019), while increased rates of criminal legal involvement challenge treatment engagement for men (Fazel, Yoon, & Hayes, 2017). However, what remains understudied is if and how the presence of fentanyl interacts with the gendered risks of opioid use among men and women.

Despite the interpersonal, community, and structural factors influencing drug use–related risks, risk reduction interventions predominately use strategies that focus on changing individual behaviors through gender-neutral education (Bungay et al., 2010; Kerr, Small, Hyshka, Maher, & Shannon, 2013; Neira-León et al., 2011). Risk communication, defined as interactions between individuals, groups, and institutions that determine, analyze, and/or manage risk, implies a two-way process whereby parties can exchange information that may result in improving risk-related outcomes (Improving Risk Communication, 1989). In the context of overdose, broad public health messaging, such as drug alerts disseminated in response to an acute overdose epidemic, have been used as a risk communication tool (Freeman & French, 1995; Kerr et al., 2013; Soukup-Baljak, Greer, Amlani, Sampson, & Buxton, 2015).

This is despite previous qualitative evidence showing gender influences preferences for risk communication. For example, young women reported preferring same-gendered physicians, and face-to-face interactions, while young men placed greater emphasis on professional appearance (Kadivar et al., 2014). Additionally, current harm reduction and substance use services, where risk communication is likely to take place, have largely developed using a “gender-neutral” approach. Due to the epidemiology of substance use and street power dynamic these services have becomes male-dominated, which has created access barriers for women (Bourgois, Prince, & Moss, 2004; Boyd et al., 2018; Bungay et al., 2010; Fraser, 2011; Simmonds & Coomber, 2009) potentially compounding the heightened risks associated with fentanyl use for women. Current public health approaches fail to address the full context in which drug use occurs and in particular the gendered dynamics of drug use risks.

While previous research has raised the need for gender-responsive overdose interventions (“Prescription Painkiller Overdoses: A Growing Epidemic, Especially Among Women,” 2013), there remains a dearth of guidance on how to apply these recommendations in practice. It is also unclear whether the calls for gender-responsive programming have been answered, and if this has actually changed the current experiences of women and men who use drugs. Given the heighted toxic properties of fentanyl, there is a need to understand its impact on the risk experiences of women and men who use opioids. Standard public health approaches to risk communication do not address the gendered dynamics of drug use highlighting an urgent research gap. This analysis explored experiences with fentanyl-related risks among women and men to inform future risk communication approaches.

2. Materials and methods

We qualitatively analyzed interview data from a study exploring overdose risk communication preferences and experiences in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) best practices (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). The current study investigated age and gender differences in fentanyl experiences and risk perceptions. We further describe the methods, dataset, and age-specific findings in a previous publication (Gunn et al., 2020). In brief, the study recruited participants from Boston-area community outreach services, syringe service programs, and primary care practices via flyers and staff outreach. We utilized purposive sampling to target two characteristics: gender (equal number of women and men) and age (two groups ages 18–25 and 35+). Additional inclusion criteria were speaking English and past year fentanyl use to garner experiences specifically related to this particular substance. Interested participants contacted the study team and arranged to be interviewed in a private space at the study site. All participants provided written informed consent during which time study staff outlined the study goals. The Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this research.

The authors (CMG, SS, and SFS) conducted in-person interviews (all interviewers were women) between May and November 2018. The study team developed a flexible, open-ended interview guide in part based on two communication-based frameworks. First, a model designed for practitioners communicating about health risks identified four principles of risk communication that the study included as interview domains. We also used the World Health Organization’s health communication framework to probe about whether participants perceived communications about fentanyl to be accessible, actionable, credible, relevant, timely, and understandable (“Communicating for health: WHO strategic Framework for effective communications,” 2017). Analysis of these communication principles are reported elsewhere. Interview topics included in this analysis relate to: 1) Fentanyl risk communication experiences, including what participants have learned about fentanyl, how and from whom; and 2) Concerns other than overdose and how participants prioritized these competing health and personal issues. All study staff received training on qualitative interview methods and the research team pilot tested interview guides on volunteer community health workers, research staff, and practicing clinicians (n=6) prior to study initiation. We estimated that interviews were would last 40–60 minutes, and participants received $50 compensation. The study audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim all interviews. Research staff (SFS, AM) verified the accuracy of transcripts against audio files to ensure fidelity.

1.2.1. Analysis

We used a grounded analysis to identify themes. The study used NVivo, a qualitative software package, to organize data and facilitate analysis. The principal investigator (CMG) drafted a codebook with deductive codes based on the risk communication frameworks and, using five transcripts, added inductive codes related to communication factors, fentanyl, and overdose risk perception (Ando, Cousins, & Young, 2014). Two of six study team members (MH, SMB, AM, SFS, SS, CMG) independently coded each transcript; then they examined each transcript for agreement (Burla et al., 2008; Eccleston, Werneke, Armon, Stephenson, & MacFaul, 2001). The same study team (MH, SMB, AM, SFS, SS, CMG) resolved coding discrepancies using a group consensus process. We examined specific codes related to risk communication, overdose, and other health or social risks attributed to drug use, and further inductively subcoded within these. We then assessed each code by interviewee gender to explore commonalities and differences in themes between women and men. This analysis focused on themes related to overdose risk communication experiences and other competing risks that women reported compared to men. We identified all quotes provided here by randomly generated pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality.

3. Results

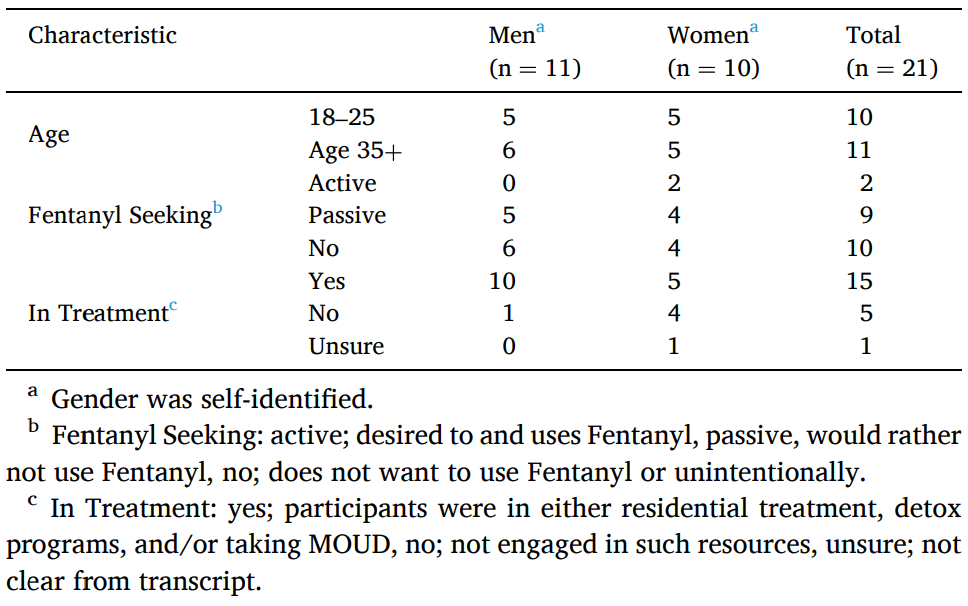

Thirty-six participants completed a screening call. Of these, seven did not arrive at the scheduled interview and were lost to follow-up, four did not meet purposive sampling criteria, and four did not meet the inclusion criteria. This study enrolled twenty-one participants: 10 women and 11 men. Interview length ranged from 35 to 75 minutes. Table 1 displays the participants’ characteristics. Half of the women (N=5) and most of the men (N=10) were actively engaged in addiction treatment at the time of interviews. All twenty-one participants described personal overdose experiences, which included having and/or witnessing an overdose. From the content analysis we distilled four themes related to risk communication that focused on overdose experiences and competing risks and report here on the commonalities and differences between women and men.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants (N=21), Boston 2019

3.1. Theme 1: Overdose as a chronic condition

Fear of overdose was common among participants and described as directly attributable to the emergence of fentanyl in the illicit opioid market. Savanah (18–25 age group) reflects, “The fentanyl… caused overdoses and caused me to witness overdoses that I don’t think would have happened necessarily back home.” Overdose was a predictable aspect of fentanyl use, as described by Alana (35+ age group): “Some people need to just stay away from [fentanyl] because they keep [overdoing], five times this girl OD’d last week. [Overdose] is becoming something that’s religiously happening”

The experience of repeated overdoses signaled to people that something changed physiologically in their body that would lead to additional overdoses. In this way, they conceptualized overdose as a chronic health condition:

And then from overdosing your brain says this is what happens when you do this. So every time after an overdose you’re more prone to overdosing again because your body is saying hey this is the time when we die. – Elise, 35+

[I’m] pretty much like a chronic overdoser because I’ve overdosed many times … I reach way over quota for people. I’ve overdosed nineteen times and I’m only twenty-one years old. – Colin, 18–25

The idea that “overdose” is a chronic condition also developed in response to risk communication experiences. Participants described receiving messages that an initial overdose makes subsequent overdoses more likely. As Colin and Eli relate: “They say once you overdose once you become chronic with it.” (Colin, 18–25), and Eli (35+) adds, “The risk they had told me I’m more vulnerable for OD quicker after I took my first, second, and third overdose. The risk is way higher now that I did OD.” This message, although derived from epidemiologic data that found a nonfatal overdose is the greatest risk factor for a fatal overdose (Larochelle et al., 2019), was interpreted by participants to be an individual determinant of overdose. The combination of personal overdose experiences and communication from health providers led to overdose being understood as a chronic and inevitable condition in women and men who used fentanyl.

3.2. Theme 2: Overdose fatalism and ambivalence toward death

Overdose was so common, participants discussed it casually and men and women considered it a typical feature of fentanyl use.

[We] talk about [overdose] without crying or being [like] oh my god we almost died. I just OD’d on that bench the other day, that should not be a laid-back conversation that you have with your friends. – Alana, 35+

These repeated overdose experiences, and the idea that overdose was a typical feature of fentanyl use resulted in participants being desensitized to the risk of overdose and death.

I overdosed and I came out of it. It didn’t even phase me in the slightest way. I came very close to death and I just kind of brushed it off, went about my day as usual. … And even now I don’t look back on it in a traumatic way or like – it honestly did not affect me. … I guess you get kind of desensitized with the use of drugs. – Brent, 18–25

One participant, Zoe (35+), used the analogy of playing “Russian Roulette” with her life while using fentanyl. Zoe also expressed ambivalence toward her own death while actively using fentanyl: “But you know, I kept doing it. And honestly… like at the time I didn’t want to live. But when I did it, I didn’t want to die. Does that make sense? … It’s so crazy.” As Jared (18–25) explains, the chronicity of overdose created a fatalistic perspective around overdose and death, a sense that things are predetermined and thus inevitable. That is, not only was overdose a typical part of fentanyl use, but so to was fatal overdose. “Well with fentanyl [it’s] just so dangerous, I mean, if I keep getting high, if I keep using, eventually I’m going to die.”

Despite ambivalence about dying, and fatalistic views about death with continued fentanyl use, participants did not identify as suicidal:

[The nurse]… was like … did you do it on purpose? And asking if I was basically trying to kill myself and I said, no. I wasn’t trying to kill myself or anything but to be honest, I’m not scared if anything would happen. I’m not suicidal or any of that but, if I was to pass away, that’s kind of the way that I would want to go. – Elise, 35+

Dean (18–25) stated that being told you might die may not be the most effective risk communication strategy precisely because overdose had become so common:

It’s a strong message, but … it hasn’t stopped me. I think for some people it might work. But I think generally, people have already gone through overdoses, like they know they’re going to die but they continue to do it anyway. So, you’re just telling them something that they already know.

The fatalistic views, developed through repeat overdose experiences, overdose being perceived as a chronic condition, and death ambivalence diminished the effects of risk communication that focused on death as a consequence of opioid use.

3.3. Theme 3: Men feared infections, violence, and incarceration and these competing risks superseded fears of overdose

All participants described competing risks, operationalized here as things besides overdose that people worried about or prioritized. Men were concerned about their general health, especially about infections secondary to their substance use. Men expressed this as being a “number one” concern. Eli (35+) reported:

One of my biggest worries, was getting HIV or getting something that I couldn’t get rid of… Not just being able to get rid of it, [but also] the stress of not knowing when you got infected, and not catching it on time.

The fear of infectious disease transmission was most commonly related to needle sharing and less often through sexual contact. Men felt control over these risks, framing needle sharing and safe sex practices as their choice:

No, I was more aware of getting a disease. I wouldn’t share with people. I was going to the exchange every day… I’m not the type of guy to go and pick up girls from the street. I don’t do that… I don’t want to catch a disease. – Mauricio, 35+

Vicente (35 +), an HIV positive participant, described choosing not to use a condom with his younger female partner.

I’m going through a situation now, with my new girlfriend. It’s been almost a couple months, but… it doesn’t bother her that I don’t use a condom. And it’s like, you know, I’m happy [she] is not, you know, looking at me in a bad way… maybe she already has this and is not telling you, [but] you’re taking the risk.

While men described HIV infection as a “number one” concern, they articulated measures they could use to reduce this risk, such as accessing sterile needles, control over sexual partner choice, and choosing to use condoms.

Some men also described fear of physical violence as a major competing risk, usually in the context of selling or buying drugs, or in retaliation for violence against others that usually occurred while they were using.

[W]hen you’re in the streets sometimes shit goes down. You know what I’m saying? You beat people. People beat you. Always looking over your shoulder… You got to do what you got to do to get high. – Matteo, 18–25

Matteo’s concern about threat of retaliation (“there’s some people like I fucked over and I could have got hurt pretty bad”) was described by some other men in the context of using, buying, or selling drugs.

Some men noted a fear of criminal legal involvement as one of their primary concerns: “[T]o tell you the truth, I was just worried about not getting caught, not going to jail” (Eli, 35+). Incarceration incited fear of withdrawal and overdose postrelease: “I was always worried about going to jail. Cause I didn’t know when I was going to go, and I didn’t know if I was going to be dope sick when I went… When I got released from incarceration in September, that was my worst run with overdosing. I overdosed four times in a span of two months.” (Colin, 18–25).

Prison was also a perceived barrier to treatment and as not well-linked to services.

And the prison system doesn’t really help you at all. … It’s a waste of time. There’s no rehabilitation inside that place. And I was trying very hard to try to make them help me out, at least to get [health care] and give me at least a list of places that I can go and try to get some help. But they never did. So I just got out, I would start using. – Mauricio, 35+

The criminal legal system kept men in the “vicious cycle” of forced detoxification and relapse. Fear of criminal legal involvement was also linked to fears of violence while selling, buying, or using drugs as there was a risk of arrest if caught fighting or assaulting others.

3.4. Theme 4: Women’s concerns for their safety, health, and responsibilities caring for children superseded fears of overdose

Women were also concerned about infections. This fear was rooted in power imbalances on the street that resulted in physical and sexual vulnerability where women did not have full control over what happened to their bodies. For example, they feared HIV infection through sex work and sexual assault.

Where I was living, just places where I needed to sleep at night… I was on the street, so … basically how I would get my money is just prostituting. So like I could get infections like that too, but I was using protection all the time. That was also something that was a big risk - causing infection or getting raped and stuff like that is a big thing too. – Theresa, 18–25

Fear about physical safety inhibited the use of harm reduction services, even though these services were close, for example only “two blocks” away. Claire (35+) articulates:

There’s no safety out there in the jungle, but we run around out there and get whatever. And I mean dirty needles, how many times ‘have you got a clean?’ You know after ten people have answered that person ‘no’. ‘Well does anyone just have one?’ Go to [syringe access program], but you can’t even walk up two blocks.

Claire’s experience highlights how her fear of violence prevented her from utilizing strategies, such as accessing sterile needles, that would otherwise reduce her risk of HIV contraction.

Violence and safety concerns, while cited by both genders, were more frequently cited and described as primary concerns by women: “I think [overdose] would be like number two. Number one would be my safety” (Theresa, 18–25). Women characterized violence as random and a constant threat.

I’m just worried about being out here and scared all the time. There’s so many things that happen. It’s so dangerous and when I stop and think about me being a woman out here walking around alone that’s not okay… [On the streets] I’m at risk of being attacked. – Alana, 35+

Risk of physical or sexual violence was exacerbated by the presence of fentanyl because it increased the risk of nonfatal overdoses. Nonfatal overdoses made women even more vulnerable, as Zoe described (35+):

[T]here was one point in my life when I did it – I don’t remember passing out. You get the drugs, you go into a room, you get high. And they leave you alone. They don’t care what happens. If you die, if you convulse, they don’t care. And in the midst of that moment, when I woke up the next morning, I don’t remember. The next morning, I had no clothes on, I was raped, okay? I was robbed.

Women also feared violence from their intimate partners. For some, relationship-based violence was a destructive force in their recovery. “When I was dating my daughter’s father…He was abusive. He used to hit me, he smashed my head open with a brick… while I was pregnant and I went to go visit him” (Anabel, 18–25).

And I fear of getting into a relationship, because relationships can also bring you down, depending on this person, can make you sound or feel like he’s going to treat you good. [But] deep into the relationship – it’s not like that. It’s abusive, verbally, physically, sexually, whatever. – Zoe, 35+

Women prioritized concerns about child protective services. Some women perceived themselves as the best “natural” mothers to their children. This intense sense of responsibility to their children buttressed concerns about losing their children and motivated recovery.

And I don’t want my daughter to be in a foster care, and I don’t want all that to come down on her too. So that’s the number one thing that I think about when I think about relapsing. – Theresa (18–25)

For some women, losing custody of their children resulted in feelings of hopelessness.

I don’t think I really cared if I OD’d or not. I was kind of at that point. I have a four-year-old daughter that I don’t have custody of, I wasn’t able to see her. I was just kind of

like well fuck it I mean if I die, I die. – Simone (18–25)

Simone’s experience also highlights her lack of agency, or control, in re-establishing a relationship with her daughter. This experience of limited power or control over their children’s care was expressed by other women as well. Lack of agency also created challenges navigating both the recovery system and re-establishing custody of children for women, as Anabel shared (18–25):

I stayed sober for a long time and I had my daughter… And then I had a couple slip-ups with cocaine … Right now we’re working on [reunification]…My fricking caseworker at the program, [my daughter] started coming all the time and now my caseworker at the program…put my visits with [my daughter] on hold because she said that it’s unorganized and that we don’t have a schedule…And I understand they need to be scheduled. But I’m working on complete reunification and in order to do that, [my daughter] needs to be here a lot. You know what I mean?… I just want my baby. I just want my baby. – Anabel (18–25)

Women broadly expressed fears for their physical and sexual safety on the street and a lack of control over choices regarding their children. Their vulnerability was exacerbated due to the presence of fentanyl and the associated risks of nonfatal overdose. The lack of control that women felt while pregnant or parenting also impacted their recoveries, as a reduced sense of agency lead to feelings of hopelessness.

4. Discussion

In a qualitative exploration of experiences with fentanyl-related risks among women and men who use fentanyl, we found that participants conceptualized overdose as a chronic health condition, and this contributed to a sense of fatalism about the risk of fatal overdose. Women and men in our study described other risks, or competing concerns, that superseded their fears of overdose and death. Men feared infections, especially HIV, violence arising from obtaining and using street drugs, and criminal legal involvement. Women feared physical and sexual violence and prioritized caring for children and maintaining relations with child protective services. The fear of street violence prevented women in our study from utilizing harm reduction services.

Participants’ personal overdose and risk communication experiences resulted in overdose being described as a chronic condition. Participants interpreted messaging describing heightened overdose risk following a nonfatal overdose, which is derived from epidemiologic data (Larochelle et al., 2019), as an individual risk ants. Participants expressed deterministic views of overdose as an inevitability and were desensitized toward overdose risk and death. Fatalistic beliefs—an outlook that events are controlled by external factors and individuals are powerless to influence them—have been studied in the context of cancer treatment and understanding the gaps in academic performance between racial minorities and white students (Cummings, 1977; Kobayashi & Smith, 2016). Rooted in structural inequities, fatalistic thinking is associated with poorer outcomes across a variety of domains, including increased risk-taking behaviors (Beeken, Simon, von Wagner, Whitaker, & Wardle, 2011; Kalichman, Kelly, Morgan, & Rompa, 1997; Niederdeppe & Levy, 2007). Structural violence—that women experienced in the male-dominated street culture and involvement with child protective services and that men experienced in their fear of criminal legal involvement—likely contributed to fatalistic views expressed in our study in addition to personal overdose experiences. Further research on risk communication that challenges deterministic thinking paired with services that address its root causes, such as structural violence, are needed for women and men who use fentanyl-containing opioids.

Our study expands on existing literature by emphasizing the importance of external factors connected to the unequal risks associated with drug use for women. Women in our study expressed challenges in navigating the omnipresent threats of physical and sexual violence. This reduced their ability to practice safer sex and limited their access to harm reduction services. These factors may explain women’s heightened risk of contracting HIV and HCV compared to men who have been described in other studies (Des Jarlais et al., 2012; Park et al., 2019). Despite previous calls for gender-responsive programs (“Prescription Painkiller Overdoses: A Growing Epidemic, Especially Among Women,” 2013), our study, like others, shows that these are lacking. Gender-neutral harm reduction spaces can become male-dominated places that reproduce the gendered relations and inequalities of the street (Boyd et al., 2018; Bungay et al., 2010; Fairbairn, Small, Shannon, Wood, & Kerr, 2008; Shannon et al., 2008). Such dynamics limit women’s service access and demonstrate the urgent need for the development and evaluation of additional women’s harm reduction spaces that focus on overdose prevention and safer injection. Organizations like SisterSpace in Vancouver British Columbia, a women’s only safe consumption space, offer a model for programs seeking to create gender-responsive harm reduction programs (Schäffer, Stöver, & Weichert, 2014).

Women in our study also highlighted concerns about their children and child services, as many women did not have custody of their children or currently had an open case with child protective services. Women, particularly pregnant and parenting women, are subject to increased surveillance, child removal, and, in some parts of the United States, prosecution and conviction for substance use (Banwell & Bammer, 2006; Stone, 2015). Thirty-six states recognize fetuses as potential victims of crime, and in 2014 Tennessee became the first state to explicitly criminalize drug use during pregnancy (Murphy, 2014). This law has increased stigma and discouraged women from accessing services that could produce better outcomes for both mother and baby (Roberts & Pies, 2011; Stone, 2015). Previous studies have shown that gender-responsive care that focuses on diminishing this heightened stigma positively impacts outcomes (S. Greenfield & Grella, 2009; S. F. Greenfield et al., 2007). Responsive programs included: the provision of childcare, women-only programs, and woman-focused mental health programming. These were positively associated with substance use treatment completion, decreased use of substances, reduced mental health symptoms, and HIV risk reduction (Ashley, Marsden, & Brady, 2003; Dahlgren & Willander, 1989; Hughes et al., 1995; O’Neill et al., 1996). Treatment programs should scale-up of these approaches and develop and evaluate programs that can provide comprehensive, supportive services for women with addiction while pregnant and parenting, in particular legal and state services.

Men in our study expressed a primary fear of incarceration. Harm reduction spaces should not be policed, as this has been shown to deter service utilization (Shannon et al., 2008). Offering criminal legal services in harm reduction programs may also enhance engagement among men and offer further opportunities for risk communication to occur. Men in our study also expressed that a central concern was infectious disease contraction, primarily HIV. Expanding HIV testing and education and connection to pre- and postexposure prophylaxis may also facilitate engagement in risk communication discussions for men who use fentanyl (Walters et al., 2020).

The findings of our exploratory study have limitations. We sampled from one geographic location, and our study includes a large proportion of people who had recently entered treatment programs, and who had experience accessing harm reduction programs. Experiences as parents, particularly for women, were found through inductive analysis. Interviewers did not systematically ask about parental status a priori. Therefore, we cannot guarantee that this study captured all parental experiences. Understanding needs over a wide range of drug use, service engagements, and housing statuses, and studying different racial groups will provide a more comprehensive picture of risk communication engagement. We also narrowed our sample to two age groups, which limited generalizability.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study can be used to explore new hypotheses around gender-related differences in perceptions of overdose risk and other risks associated with drug use, in particular fentanyl use. Future interventions might test whether incorporating concerns other than overdose, like violence, separation from children, and criminal legal involvement, into harm reduction programs will engage a more people at risk for overdose. Furthermore, the development of gender-responsive programs that address targeted concerns may create safer spaces for women not currently accessing such services. Future research should incorporate the perspectives of individuals connected to people who use fentanyl, including child protective services’ case workers, members of the court system, family members, and others, to develop a broader understanding of service design and provision that meet the unique needs women and men.