Abstract

The Supreme Court has explored the issues of culpability, proportionality, and deserved punishment most fully in the context of capital punishment. In death penalty decisions addressing developmental impairments and culpability, the Court has considered the cases of defendants with mental retardation and older adolescents, and has created an anomalous inconsistency by reaching opposite conclusions about the deserved punishment for each group of defendants. Recently, in Atkins v. Virginia, the Court relied on both empirical and normative justifications to categorically prohibit states from executing defendants with mental retardation. Atkins reasoned that mentally retarded offenders lacked the reasoning, judgment, and impulse control necessary to equate their culpability with that of other death-eligible criminal defendants. This Article contends that the same psychological and developmental characteristics that render mentally retarded offenders less blameworthy than competent adult offenders also characterize the immaturity of judgment and reduced culpability of adolescents and should likewise prohibit their execution. Moreover, the diminished criminal responsibility of adolescents has broader implications for proportionality in sentencing young offenders. Because the generic culpability of adolescents differs from that of responsible adults, penal proportionality requires formal, categorical recognition of youthfulness as a mitigating factor in sentencing.

INTRODUCTION

Proportionality between the seriousness of the harm, the culpability of the actor, and the severity of punishment constitutes the foundation of the criminal sanction.1 In its noncapital proportionality analyses, the Supreme Court has primarily emphasized the relationship between the seriousness of the offense or recidivism and the sentence imposed, rather than the culpability of the offender.2 By contrast, the Court's death penalty jurisprudence has repeatedly emphasized that defendants must receive an individualized culpability assessment before a state may impose the ultimate penalty.3

The criminal law assumes that rational actors possess free will and choose to violate the law based on their own preferences and values. Because moral blameworthiness provides legitimacy to the criminal sanction, the criminal law must account for the quality of choices made by actors who deviate substantially from its model of personal autonomy. Some nominally responsible actors are not as blameworthy as other offenders, and the criminal law formally or informally mitigates the punishment of those with "diminished capacity." Because the idea of deserved punishment emphasizes culpability and blameworthiness, the criminal law confronts the special cases of those who are criminally responsible and yet manifestly impaired, mentally ill, or developmentally different from competent adult offenders.4 The criminal law distinguishes doctrinally between the profound disabilities that fully excuse actors from criminal liability, such as insanity,5 which the law defines very narrowly, and doctrines of "diminished responsibility" or "reduced culpability," which allow even seriously impaired actors to be convicted and punished for their crimes.6 The relationship between culpability and deserved punishment implicates interrelated notions of blameworthiness, responsibility, and personal accountability. What types of impairments mitigate or reduce criminal culpability? How much impairment must be present to warrant a reduction in severity of sanctions? How are impairments of judgment and culpability to be defined and proved? Should the law assess and treat such impairments individually or categorically?

The Supreme Court most thoroughly explored culpability, proportionality, and deserved punishment in the context of the death penalty because "death is different.",7 In decisions involving the culpability of defendants with mental retardation and older adolescents, the Court has reached opposite conclusions about the deserved punishments of each category and produced an anomalous inconsistency.8 In 1989, the Court in Penry v. Lynaugh held that mentally retarded defendants could be found as culpable as other criminal offenders facing the death penalty.9 Although a plurality of justices in Thompson v. Oklahoma10 had earlier concluded that fifteen year-old offenders lacked the culpability necessary to impose the death penalty,11 the Court in Stanford v. Kentucky, decided at the same time as Penry, upheld the death penalty for youths who were sixteen or seventeen years of age at the time of their offenses.12 More recently, the Court in Atkins v. Virginia overruled Penry and held that the Eight Amendment barred states from executing mentally retarded defendants.13 Atkins found that mentally retarded defendants lacked the reasoning, judgment, and impulse control necessary to equate their moral culpability with that of ordinary adult criminal defendants.14 In addition, their mental impairments detracted from the fairness and reliability of capital trials and increased the likelihood of erroneous death sentences.15

In this Article, I argue that the Court's culpability analyses in Atkins apply equally to the execution of adolescents and should prohibit the practice. Moreover, the rationale of diminished criminal responsibility of adolescents has broader implications for proportionality in sentencing all younger offenders in criminal courts. Part I analyzes the Atkins decision, which relied on empirical and normative justifications to prohibit executing mentally retarded offenders. Empirically, Atkins analyzed state death penalty laws and jury practice and found a national consensus that executing defendants with mental retardation violated "evolving standards of decency." Normatively, the Court examined the psychological and developmental characteristics of mentally retarded offenders that render them less blameworthy than more competent adult offenders. Part II reviews the Court's juvenile death penalty analyses in Thompson and Stanford, follows the framework of Atkins' empirical analysis, and assesses recent legislative and judicial activity regarding execution of sixteen- and seventeen-year-old offenders. Part III builds on Atkins' normative description of developmental characteristics of mentally retarded offenders, compares them with the developmental, psychological, and neuro-biological characteristics of adolescents, and argues that their similar limitations of judgment reduce their culpability as well. Adolescents' limitations in adjudicative competence also increase their risks of erroneous convictions. Based on these empirical and normative comparisons, I argue that Stanford is inconsistent with the Court's more enlightened appraisal of culpability in Atkins and logical consistency should preclude states from executing youths for crimes they committed when sixteen or seventeen years of age. Part IV extends the culpability and proportionality analyses to the sentencing of noncapital young offenders as well. Because adolescents' competence and culpability differ qualitatively from those of adults, courts and legislatures should formally recognize youthfulness as a mitigating factor. I argue for a bright-line, rather than an individualized discretionary approach, because the generic culpability of adolescents differs from that of adults and categorical treatment of penal proportionality reduces the risks of error and injustice in sentencing.

I. CULPABILITY, MENTAL RETARDATION, AND ATKINS

The Supreme Court has interpreted the Eighth Amendment's16 prohibition on "cruel and unusual punishment" to bar sentences that are "excessive,"17 that fail to contribute to the penal goals of retribution and deterrence,18 and that violate "evolving standards of decency."19 For more than a quarter of a century, the Court has required state death penalty statutes to channel jury discretion and consider the circumstances of the defendant.20 Trial courts must allow defendants to present to the jury any evidence that humanizes them or mitigates their culpability before the jury renders its verdict.21 The Court endorses structured, individualized discretion in capital sentencing and only rarely has excluded whole classes of offenders from death eligibility.22

The Supreme Court in Penry v. Lynaugh23 held that the Eighth Amendment did not categorically bar executing mentally retarded criminal defendants.24 The Court looked to state statutes as "objective evidence of how our society views a particular punishment today" and found that only two states and the federal government prohibited execution of mentally retarded offenders.25 Even when coupled with the fourteen states that rejected capital punishment, the Court concluded that Penry had failed to "provide sufficient evidence at present of a national consensus" opposed to executing mentally retarded defendants.26 Although the Court rejected Penry's plea for a categorical ban on executing defendants with mental retardation, it remanded his case for individualized reconsideration of his death sentence.27 "[I]t is precisely because the punishment should be directly related to the personal culpability of the defendant that the jury must be allowed to consider and give effect to mitigating evidence relevant to a defendant's character or record or the circumstances of the offense.28 However, the Penry Court acknowledged that "a national consensus against execution of the mentally retarded may someday emerge.29

Thirteen years later, the Court in Atkins v. Virginia30 reconsidered its decision in Penry, found that a national consensus had emerged, and held that executing mentally retarded defendants categorically violated the Eighth Amendment.31 The Court used both empirical evidence and normative judgments to support its conclusion that executing mentally retarded offenders violated "evolving standards of decency." It relied on objective indicators of a national consensus, such as state laws and jury practices.32 The justices also relied on their own judgments about diminished culpability and deserved punishment to support their proportionality determination.33 In its empirical analysis, the Court surveyed the trend of states' laws on the execution of retarded offenders.34 In its normative assessment, the Court drew on several clinical definitions of mental retardation to identify the characteristics of mentally impaired offenders that rendered them qualitatively less culpable than ordinary adult offenders and thus justified the blanket prohibition against executing the mentally retarded.35

First, the Court analyzed death penalty laws regarding the execution of the mentally retarded. While only two states and the Federal government prohibited executing mentally retarded defendants when the Court decided Penry,36 by the time the Court reconsidered its holding in Atkins, sixteen additional states had prohibited the practice, and prohibition bills had passed at least one house in several other states.37

The Court suggested that several other states had not adopted explicit legislation because they had not executed a mentally retarded defendant in decades.38

It is not so much the number of these States that is significant, but the consistency of the direction of change. Given the well-known fact that anticrime legislation is far more popular than legislation providing protections for persons guilty of violent crime, the large number of States prohibiting the execution of mentally retarded persons (and the complete absence of States passing legislation reinstating the power to conduct such executions) provides powerful evidence that today our society views mentally retarded offenders as categorically less culpable than the average criminal.39

The Court attributed the states' emerging legislative consensus to the normative recognition that mentally retarded defendants are less culpable or deserving of retributive punishment and less susceptible to the deterrent threat of execution than ordinary offenders.40 Atkins examined the penal functions presumably served by the death penalty -- retribution and deterrence --and concluded that executing a mentally retarded defendant accomplished neither goal. Even though states could find mentally retarded offenders competent and punish them for their crimes, they lacked the culpability necessary to justify the ultimate penalty.41 Similarly, they lacked the deliberative capacity that would respond to the deterrent threat of execution.42 Moreover, their developmental limitations substantially increased the likelihood that they erroneously might receive the death penalty.43 Thus, mental retardation simultaneously reduced offenders' culpability and adversely affected their adjudicative competence.

The Court relied on several professional definitions of mental retardation to identify the clinical characteristics that reduced the criminal responsibility and hampered the adjudicative competence of defendants with mental retardation.44 Findings of

mental retardation require not only subaverage intellectual functioning, but also significant limitations in adaptive skills such as communication, self-care, and self-direction that became manifest before age 18. . . . Because of their impairments ... they have diminished capacities to understand and process information, to communicate, to abstract from mistakes and learn from experience, to engage in logical reasoning, to control impulses, and to understand the reactions of others .... [Tlhey often act on impulse rather than pursuant to a premeditated plan, and.., in group settings they are followers rather than leaders. Their deficiencies do not warrant an exemption from criminal sanctions, but they do diminish their personal culpability.45

In addition to significant subaverage intellectual functioning,46 a retarded individual also demonstrates actual disability in "adaptive skill areas" that affect every day life, such as the capacity to use and process information, to reason logically, to control impulses, and to resist peer pressure.47 While a low IQ provides one indicator of mental retardation, Atkins emphasized a broader range of social, psychological, and mental skills deficits to justify its conclusion that such offenders lacked the requisite culpability.48 The features that Atkins found to reduce culpability of mentally retarded defendants-- possessing, understanding, and using information; exercising impulse control; and responding to negative peer influences49-- are normal developmental characteristics of ordinary adolescent offenders as well.50

In addition to reducing culpability, mental retardation also adversely affects defendants' adjudicative competence and increases the likelihood that they erroneously might receive the death penalty.51 Mentally retardation increased defendants' susceptibility to interrogation and proclivity to give false confessions, reduced the assistance they could provide to their lawyers, and adversely affected their demeanor and effectiveness as witnesses.52 Because the Court recognized that mental retardation and diminished culpability are matters of degree on a continuum, it left the task to the states to develop legislative definitions and criteria, procedures, and clinical indicators to identify which defendants its categorical ban protected.53

In separate dissenting opinions, Justices Rehnquist and Scalia, each joined by the other and by Justice Thomas, criticized the Court's categorical ban on executing mentally retarded defendants. Justice Rehnquist objected to the proportionality analysis the majority used to find a national consensus against executing mentally retarded offenders.54 He insisted that state laws provide the most objective and reliable basis on which to ascertain the existence of a national consensus and to avoid the Justices imposing their own subjective preferences on the states' power to legislate.55 He decried the majority's reliance on foreign laws, opinion polls, and the positions of professional and religious groups reported in amici briefs as "a post hoc rationalization for the majority's subjectively preferred result rather than any objective effort to ascertain the content of an evolving standard of decency."56 Justice Scalia derided the majority's conclusion as "nothing but the personal views of its [m]embers."57 He insisted that legislation provides the only objective basis for identifying a national consensus and disputed the mathematical calculations that the majority used to find a consensus against executing the mentally retarded.58

II. CULPABILITY, ADOLESCENCE, AND THE RATIONALE OF THOMPSON AND STANFORD

Characteristics that reduce the culpability of mentally retarded offenders-- susceptibility to peer influences, a propensity to act impulsively without thinking about consequences, and immaturity of judgment-- have relevance to the criminal responsibility of adolescents.59 Although earlier decisions adverted to youthfulness as a mitigating factor in capital sentencing,60 the Court in Thompson v. Oklahoma61 analyzed the criminal responsibility of youths older than the common law infancy threshold of age fourteen. Thompson presented the issue of whether executing a fifteen-year-old offender for a heinous murder in which he actively participated violated the prohibition on "cruel and unusual punishments."62 A four-justice plurality held that the Eighth Amendment categorically precluded executing youths who were fifteen years of age or younger at the time they committed their offense.63 Justice O'Connor wrote a separate concurrence on the grounds that the Oklahoma legislature may not specifically have considered that fifteen-year-old youths would be death eligible.64

As the Court would later in Atkins, the Thompson plurality looked both to objective indicators of "evolving standards of decency," such as state statutes and jury practices and the views of national and international organizations, and to the justices' own subjective sense of "civilized standards of decency" when it conducted its proportionality analysis.65 Of the states that explicitly had considered a minimum age for death penalty eligibility, all had established it at sixteen, seventeen, or eighteen years of age.66 Similarly, the Court found that juries rarely imposed the death penalty on juveniles.67 Thompson noted that legal, professional, religious, and social organizations-- nationally and internationally-- opposed executing young people.68 Moreover, international law and treaties also condemned the practice.69 Based on these objective indicators, the Court concluded that executing offenders who committed their crimes before they turned sixteen-years-old was generally abhorrent to the conscience of the community.70

In addition to the objective factors, the plurality concluded that "a young person is not capable of acting with the degree of culpability that can justify the ultimate penalty," and vacated Thompson's capital sentence.71 The justices asserted that

[L]ess culpability should attach to a crime committed by a juvenile than to a comparable crime committed by an adult.... Inexperience, less education, and less intelligence make the teenager less able to evaluate the consequences of his or her conduct while at the same time he or she is much more apt to be motivated by mere emotion or peer pressure than is an adult. The reasons why juveniles are not trusted with the privileges and responsibilities of an adult also explain why their irresponsible conduct is not as morally reprehensible as that of an adult.72

Even though Thompson could be found criminally responsible for his crime, he could not be punished as severely as an adult simply because of his age-- "adolescents as a class are less mature and responsible than adults.73 Even though youths may inflict blameworthy harms, their choices evidence less culpability than do those of adults.74 The legal system treats adolescents differently from adults in numerous areas of life-for example, serving on a jury, voting, marrying, driving, and drinking-because of youths' inexperience and immature judgment.75 In all these instances, the state acts paternalistically and imposes legal disabilities because of youths' presumptive incapacity to "exercise choice freely and rationally."76 It would be inconsistent and cruelly ironic to find juveniles' culpability and criminal capacity equivalent to that of adults for purposes of capital punishment.77 The plurality concluded that categorically exempting younger adolescents from the death penalty would not erode the retributive and deterrent justifications for capital punishment.78 Some commentators criticized the Court's categorical ban on executing children as contrary to its insistence on individualized consideration of the culpability of offenders.79

Justice O'Connor concurred in the reversal of Thompson's capital sentence.80 She acknowledged the likelihood of the existence of a national consensus that persons who commit crimes before the age of sixteen should not be executed, but questioned the sufficiency of the evidence to support that conclusion.81 She noted that every state that had established a minimum age for the death penalty had set it at sixteen years of age or older.82 She joined the plurality on the narrower grounds that states with no minimum age for death-eligibility may not have adequately considered the interaction of provisions that waive juveniles of any age for adult criminal prosecution and statutes that permit the state to execute any youth convicted as an adult83 As a result, Oklahoma may not have affirmatively decided to execute very young offenders.84

The following year, in Stanford v. Kentucky,85 the three justices who dissented in Thompson,86 joined by Justices O'Connor and Kennedy, mustered a majority to uphold the death penalty for youths who were sixteen or seventeen at the time of their offenses.87 While Stanford recognized that juveniles as a class possess less culpability than do adult offenders, the Court's decision rested on the narrow grounds that no clear national consensus existed that such executions violated "evolving standards of decency."88 According to Justice Scalia, "statutes passed by society's elected representatives" provide the only reliable indicator of a national consensus and the majority of states that employ capital punishment approve it for youths who were sixteen or seventeen years of age at the time of their offense.89 The Court rejected a categorical ban on all such executions because it regarded at least some older adolescents as capable of acting with the culpability necessary to justify the death penalty.90 The Court distinguished other types of brightline classifications of youths, for example, the right to vote, drink, or drive, because the criminal justice system provided youths with an individualized culpability assessment prior to imposing the death penalty.91 Indeed, Justice Scalia erroneously asserted that juvenile court judges made an initial culpability determination prior to transferring youths to criminal court for prosecution as adults.92 Because most states now "automatically" prosecute older juveniles charged with capital crimes as adults, courts have relied on Justice Scalia's assertion to invalidate death sentences imposed on youths who did not receive an individualized assessment of their maturity and culpability prior to trial.93 Justice O'Connor concurred to uphold the death penalty for sixteen- and seventeen-year-old offenders because the majority of states that endorsed capital punishment authorized it for those below the age of eighteen.94

The four Stanford dissenters reviewed the evidence relied on in Thompson to argue for a national consensus against executing children.95 In its calculus, the dissent counted both those states that did not authorize the death penalty for any offender as well as those which restricted it only to those eighteen years of age or older, and found that "the governments in fully 27 of the States have concluded that no one under 18 should face the death penalty" and that "a total of 30 States... would not tolerate the execution" of the sixteen-year-old petitioner in Stanford's companion case.96 Unlike the majority, the dissent would consider other "indicators of contemporary standards of decency" besides state laws and jury practices.97 The Eighth Amendment requires the Court to conduct an independent proportionality analysis to determine whether a punishment was disproportionate or served the goals of punishment.98 Such a proportionality analysis precludes "punishment that is wholly disproportionate to the blameworthiness of the offender,"99 and juveniles categorically lacked the requisite culpability for capital punishment.100 Moreover, the procedural safeguards on which the Stanford majority relied did not adequately address the substantive questions of whether any youth can possess the requisite culpability for execution or whether states accurately can distinguish them from less blameworthy offenders.101

Atkins has revived questions about the constitutionality of executing adolescents. In Patterson v. Texas, the dissent to a denial of a stay of execution of a juvenile urged the Court to reconsider Stanford in light of the "apparent [national] consensus that exists among the States... against the execution of a capital sentence imposed on a juvenile offender."102 Two months after Patterson, Stanford exhausted his state and federal remedies and filed a final writ of habeas corpus, which the Court denied.103 The four justices, who dissented from the denial of the writ, argued that a national consensus had emerged against executing juveniles, and urged the Court to reconsider the issue in light of Atkins.104 Justice Stevens noted that nearly the same number of states prohibited executing adolescents as proscribed the death penalty for defendants with mental retardation.105 Justice Stevens also cited recent neurobiological research that indicates that the immature adolescent brain lacked the reasoning abilities of adults.106 On January 5, 2004, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Roper v. Simmons to consider again whether the Eighth Amendment bars the execution of offenders for crimes they committed prior to age eighteen.107

A. The Empirical Foundation of Stanford

Atkins relied on legislative changes and jury behavior as empirical evidence to prohibit states from executing mentally retarded defendants.108 In the decade and a half since Stanford, several state supreme courts have barred the execution of youths under eighteen,109 or at least under seventeen years of age.110 In Simmons v. Roper,111 the Missouri Supreme Court applied the Supreme Court's Atkins analysis to prohibit execution of a youth for a crime committed at seventeen years of age:

Applying the approach taken in Atkins, this Court finds that, in the fourteen years since Stanford was decided, a national consensus has developed against the execution of juvenile offenders, as demonstrated by the fact that eighteen states now bar such executions for juveniles, that twelve other states bar executions altogether, that no state has lowered its age of execution below 18 since Stanford, that five states have legislatively or by case law raised or established the minimum age at 18, and that the imposition of the juvenile death penalty has become truly unusual over the last decade." 112

Significantly, the Missouri Supreme Court based its decision on federal constitutional grounds and found that "the Supreme Court would today hold that such executions are prohibited by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments."113 By ruling on the federal, rather than state, constitution, Simmons frontally challenged the continuing vitality of Stanford.114

Simmons replicated the Supreme Court's empirical and normative analyses in Thompson115 and Atkins116 and concluded that the Court today would prohibit executing offenders under the age of eighteen.117 The same legislative trend that Atkins found to provide a "national consensus" against executing mentally retarded defendants also existed with respect to state laws prohibiting executing juveniles.118 Although twenty-one other states theoretically authorized the death penalty for juveniles, only six states had executed a juvenile since the Stanford decision, and only three had done so within the preceding decade.119 Simmons found that national and international professional, social, and religious organizations opposed executing offenders for crimes committed when they were younger than eighteen years of age.120 Because of juveniles' reduced culpability, categorically exempting them from the death penalty would not erode the retributive or deterrent functions of the death penalty.121

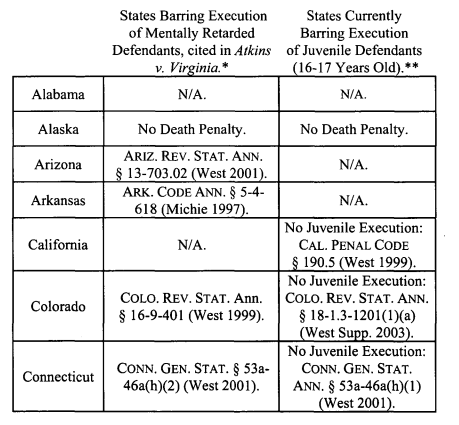

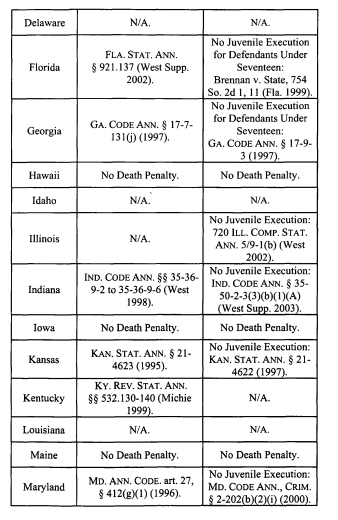

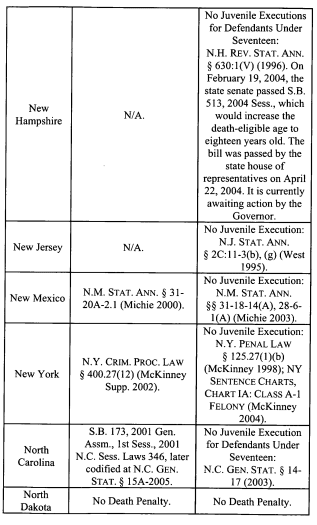

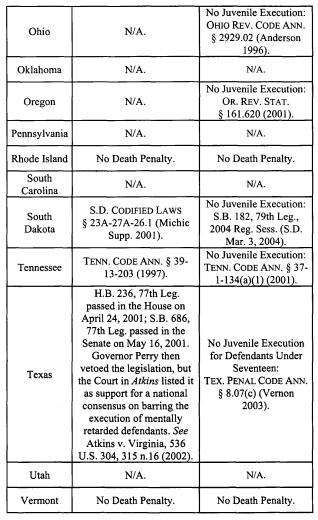

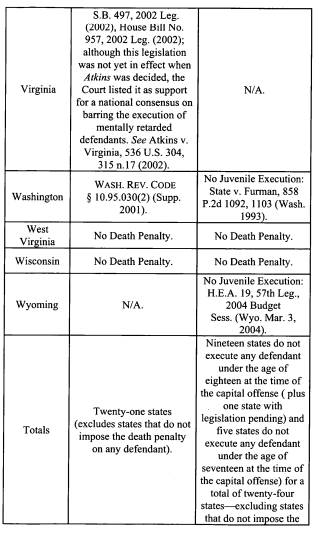

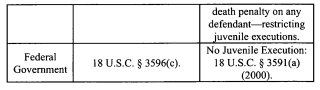

* All of the statutes listed in the Atkins v. Virginia column were cited by the Supreme Court in Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 314-16 (2002), and appear here as in effect at the time Atkins was decided. States designated as "N/A" either permitted execution of the mentally retarded at the time Atkins was decided, or prohibited it but were not cited in that decision.

** The Supreme Court held that the execution of a defendant that was under sixteen years of age when he committed his crime was unconstitutional in Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 815 (1988). States in this column designated as "N/A" do not bar the execution of sixteen and seventeen year olds.

Following the Simmons ruling, two more states-- South Dakota and Wyoming-- passed laws banning the execution of juveniles, and the New Hampshire house and senate also passed a prohibition bill. Of the thirty-eight state death penalty jurisdictions and the two federal government (civil and military) jurisdictions, twenty-one (52.5 %) expressly provide that eighteen years of age is the minimum age for death eligibility, another five (12.5 %) specify seventeen years of age as the minimum age for death eligibility, and fourteen (35 %) use sixteen years of age as the minimum age either by statute or by court ruling relying on Stanford.122 Even after Stanford approved executing sixteen or seventeen-year-old offenders, no death penalty state which previously allowed executing only eighteen-year-old offenders lowered its statutory minimum age.123 Like the clear national trend observed in Atkins, states consistently have moved only to raise the minimum age for death eligibility. In the post-Stanford era, several states have adopted or raised their minimum age from sixteen to eighteen,124 and several other legislatures have come close to amending their death penalty statutes to prohibit executing juveniles.125

The dissent in Atkins and the Thompson Court viewed jury sentencing practices as another indicator of "evolving standards of decency."126 Even in states that nominally approve the death penalty for juveniles, juries seldom impose them and states even less frequently carry them out thereby reducing the impetus to amend their laws. Although twenty-two states officially sanctioned the death penalty for juveniles, at the time Simmons v. Roper was decided, only seven states have executed a juvenile during the post-Furman era, and since Stanford, only Texas, Oklahoma, and Virginia have executed youths with any regularity.127 In Texas, between 1982 and 2003, of the three hundred and thirteen persons executed, thirteen (4.2 %) were juvenile offenders, and an additional twenty-eight youths remain on death row.128 During the same period in Virginia, three (3.4 %) of eighty-nine people executed were juveniles.129 The decision by the jury in Virginia to spare the life of seventeen-year-old Washington, D.C.-area sniper, Lee Boyd Malvo, also evidences the erosion of popular support for the practice.130

III. ATKINS AND ADOLESCENTS RECONSIDERED: COMPETENCE AND CULPABILITY

The developmental limitations that reduce the culpability of mentally retarded defendants characterize most normal adolescent offenders as well.131 When states punish young offenders, they assume that adolescents possess sufficient cognitive capacity and volitional controls to hold them responsible and accountable for their criminal behavior.132 However, even criminally responsible young offenders deserve less severe penalties than do mature offenders.133 Every other area of law recognizes that young people have limited judgment, are less competent decision-makers because of their immaturity, and require greater protection than do adults.134 Applying the same principle of diminished responsibility in the criminal law requires a categorical ban on executing youths and shorter sentences for youths than for adults convicted of the same offenses.

Deserved punishment entails condemnation for making blameworthy choices and imposes proportional 'sentences commensurate with the seriousness of the offense.135 Two elements define the seriousness of a crime-harm and culpability.136 An offender's age has little bearing on assessments of harm-- the quality of the injury inflicted or the value taken137-- but youthfulness and immaturity bear quite directly on the quality of choices, the culpability of the actor, and the moral seriousness of the crime.138

In the context of homicide gradations, for example, criminal law arrays actors' culpability and blameworthiness along a continuum from a premeditated killer for hire at one end to the minimally responsible actor barely capable of discerning right from wrong at the other end, even though each caused the same harm.139 Assigning sentences proportional to culpability attempts to gauge the actor's location along this continuum of responsibility. Although determinations of culpability reflect complex moral evaluations, judgments about blameworthiness also reflect an actor's response to external factors, such as provocation, and to individual psychological, developmental, or emotional features, subsumed as "diminished responsibility."140 Because the criminal law presumes free-willed moral actors-those who morally can be blamed for wrong-doing-it deems less culpable those whose capacity to make rational choices or whose ability to exercise self-control is significantly constrained by external circumstances or individual impairments.141 Youthfulness affects the actor's abilities to reason instrumentally and freely to choose behavior, and locates an offender closer to the diminished responsibility end of the continuum than to the fully autonomous free-willed actor.142

Criminal responsibility and moral blameworthiness hinge on cognitive and volitional competence. In a framework of deserved punishment, it is unjust to impose the same penalty on offenders who do not possess comparable culpability. Younger offenders are not as blameworthy as adults because they have not yet fully internalized moral norms, developed sufficient empathic identification with others, acquired adequate moral comprehension, or had sufficient opportunity to learn to control their actions.143 In short, they possess neither the rationality-- cognitive capacity-- nor the self-control-- volitional capacity-- to justify equating their criminal responsibility with that of adults.

Developmental psychology studies changes across the life-cycle in physical, social, intellectual, and emotional development,144 and, from its earliest foundation, has posited that young people move through a sequence of stages in legal reasoning and moral decision making.145 Some of the developmental changes parallel the imputations of responsibility associated with the common law infancy defense, and by mid-adolescence most youths acquire cognitive reasoning capacity roughly comparable to that of adults.146 When, for example, youths make informed consent decisions for psychotherapy or medical treatment, few bases exist to distinguish between mid-adolescents and adults in terms of the information used or the reasoning processes employed.147 Studies that equate adolescent and adult cognitive ability derive primarily from informed consent research that emphasizes subjective preferences.148 But the ability to make hypothetical decisions under structured laboratory conditions with complete information differs significantly from the ability to exercise mature judgment when equipped with incomplete knowledge, under stressful conditions, and with real-life consequences.149

From a clinical and social policy perspective, there is increasing recognition of the importance of emotions in decision making, relevant to a wide range of risk-taking behaviors. In many ways, this perspective increasingly blurs the traditional boundaries of cognitive vs. emotional processes. This is important because the "decision" to engage in a specific behavior that has long-term health consequences-e.g., smoking a cigarette, drinking alcohol, or engaging in unprotected sex-cannot be completely understood within the framework of "cold" cognitive processes. Cold cognition refers to thinking under conditions of low emotion and/or arousal, whereas hot cognition refers to thinking under conditions of strong feelings or high arousal. The cognitive processes involved in hot cognition may, in fact, be much more important for understanding why people[--especially youths-] make risky choices in real-life situations.150

While adolescents' cognitive abilities to think and to reason may be comparable to adults', youths' interpersonal context, emotional responsivity, and inexperience affect the quality of their choices and behavior.151

While psycho-social development proceeds through a series of stages, decision-making competencies emerge unevenly rather than as a uniform increase in overall capacity, and young people use different reasoning processes in different task domains.152 Differences in language ability, knowledge, experience, and culture affect the ages at which youths' various competencies emerge.153 Many characteristics of delinquent youths-lower intellectual ability, poverty, social disadvantage, and cultural isolation-further hamper cognitive development and competent legal decision-making.154

A. Atkins, Adolescents, and Reduced Culpability

Atkins prohibited executing mentally retarded defendants because "their disabilities in areas of reasoning, judgment, and control of their impulses" prevented them from acting "with the level of moral culpability that characterizes the most serious adult criminal conduct."155 Similarly, adolescents think qualitatively differently than adults, and their poor judgment, psycho-social immaturity, and truncated self-control also require a different criminal sentencing policy.156 It is important to distinguish between cognitive competencies, which affect decision-making processes, and maturity of judgment, which affects the quality of decisions.

This is so because psycho-social developmental factors influence values and preferences, which in turn shape the cost-benefit calculus, which determines outcomes. The influence of these factors will change as the individual matures and values and preferences changeresulting in different choices.... [T]he intuition is that developmentally linked predispositions and responses systematically affect youthful decision making in ways that may lead to harmful choices.157

While adolescents possess sufficient cognitive competency to justify some degree of punishment, psycho-social maturity of judgment and temperance provide a broader framework through which to assess their culpability.158 Most youths lack the maturity of judgment characteristic of adulthood in a variety of areas--- perceptions of risk, appreciation of future consequences, capacity for self-management, and ability to make autonomous choices.159 Their decision-making preferences and values are in a state of transition, and they are prone to make poorer judgments than they would make several years later.160

Youths differ from adults in their breadth of experience, short-term versus long-term time perspective, attitude toward risk, impulsivity, and the importance they attach to peer influence.161 These differences are linked to developmental process and affect their qualities of judgment and ability to appreciate the consequences of their actions. These generic developmental differences justify a less punitive stance toward younger offenders, which allows them to survive the mistakes of adolescence.

1. Risky Behavior

Young people act more impulsively, exercise less self-control, more frequently fail adequately to calculate long-term consequences, and therefore engage in more risky behavior than do adults.163 Risky behavior may be developmentally necessary for adolescents to acquire the skills needed to negotiate successfully the transition to adulthood.164 Adolescents need to learn to function independently of parental caretakers.165 Acquiring these skills entails certain characteristic behaviors such as "increases in peer-directed social interactions and elevations in novelty-seeking and risk-taking behaviors."166

This developmental transition is disruptive and entails opportunities for growth as well as dangers. "Adolescents are risk takers. Relative to individuals at other ages, human adolescents as a group exhibit a disproportionate amount of reckless behavior, sensation seeking and risk taking ... "167 Compared to adults, adolescents generally underestimate the magnitude or probability of risks, use a shorter time-frame, and focus on opportunities for gains rather than possibilities of losses.168 The greater prevalence of accidents, suicides, and homicides as causes of death of the young reflects greater "risk-taking" behavior.169 Criminal behavior is a particularly risky form of behavior, and every theory of crime attempts to account for its greater prevalence during adolescence.170

Risk entails a chance of loss, as well as gain, and risky behavior exposes the actor to potential adverse consequences.171 A decisionmaker must identify possible outcomes, identify consequences that may follow from each option, evaluate the desirability of positive or negative results, estimate the likelihood of those various events occurring, and make a choice to optimize outcomes.172 Adolescents may approach these decision-making steps differently than adults when they engage in riskier behavior. Youths may possess or use different amounts of information when they make decisions.173 Unlike informed consent studies conducted under laboratory conditions, in less-structured, real life circumstances, adolescents simply may know less about risks than do adults.174 They may perceive fewer alternative options than do adults.175 Young people may discount negative future consequences because they have more limited experience. Disadvantaged youths, in particular, may feel a sense of "futurelessness," fatalism, and despair, which inclines them to discount future consequences even more than do other teenagers.176

Even when adolescents possess and use comparable information, they may assign different subjective values to the alternative consequences.177 Youths may weigh benefits and consequences differently and discount negative future consequences in ways that skew the quality of their choices.178 In some instances, youths simply may estimate negative consequences of risky behavior as having lower probabilities of occurring than do adults. In other cases, youths' subjective valuations of risks and consequences may cause them to make different choices than adults.179 In addition, adolescents may weigh the consequences of not engaging in risky behaviors differently than adults.180 Youths' unrealistic optimism and feelings of "invulnerability" and "immortality" further contribute to risk-taking behavior.181

A predisposition toward sensation-seeking inclines adolescents to seek exciting and novel activities. Risk-taking can be fun, and successful experiences may enhance self-esteem.182 Youths seek novelty and take risks as part of the process of separating from family and becoming autonomous.183 They experience more difficulty controlling their impulses than do adults because of physiological changes, mood volatility, and predisposition toward sensation-seeking.184 Youths engage in risky behavior for the excitement of the "adrenaline rush.185 As a result of habituation, they may require more intense and novel stimuli to achieve the desired affect.186 "[D]ecision-making sequences regarding risky behavior in adolescence cannot be fully understood without considering the role of emotions, with key aspects of these 'decision' processes involving interactions between thinking and feeling processes."187 Adolescents' predisposition toward risk reflects generic developmental processes rather than malevolent personal choices.

2. Peer Group Influences

Atkins noted that mentally retarded offenders are followers in groups; similarly, adolescents also respond to peer group influences more readily than do adults.188 Adolescents typically commit their crimes in a group context, and group-offending puts normally law-abiding youth at greater risk to commit crimes and reduces their ability publicly to withdraw.189 The social setting of adolescent offending increases youths' difficulty with resisting peer pressure.190 Indeed, adolescents' proclivity toward risk-taking and susceptibility to peer influences likely interact to produce even riskier behavior in a group setting.191 In some social contexts, youths' struggles to achieve autonomy and to define a social identity may require adherence to subcultural norms that provide powerful pressures to engage in criminal activity.192 Because of the social setting of youth crime, young people need time, experience, and opportunities to develop the ability to make independent judgments and to resist peer influence.193 While an inability to resist peer pressure does not excuse criminal conduct, youths who have not yet learned to manage peer relations successfully are not as responsible for their behavior as we hold adults to be.194

3. Communities and Dependence

Children depend on adults to care for them and to enable them to develop the capacity for positive behavior and moral action.195 The ability to exercise self-control is the outcome of a socially constructed developmental process in which families, schools, and communities share responsibility.196 Community structures affect the conditions within which young people grow, interact with peers, and experience the risks of criminal involvement.197 Neighborhoods characterized by weak informal social controls provide greater opportunities for criminal activity and contribute to the higher crime rates in inner-city areas.198

Community settings also affect youths' opportunities to learn and practice responsible behavior.199 Unlike presumptively mobile adults, juveniles' dependency limits their ability to escape from criminogenic environments.200

4. Adolescent Brain and Neurobiology

Developmental psychologists consistently report differences between the thinking and behavior of children, adolescents, and adults. Recent neuroscience research suggests that these behaviors reflect more fundamental dissimilitude in brain development, biological maturation, and intellectual functioning.201 In short, a "hard-science" explanation may exist for the "soft-science" observations of social scientists.202 Neurobiological evidence suggests that the human brain does not achieve physiological maturity until the early twenties and that adolescents simply do not have the same physiologic capability as adults to make mature decisions or to control impulsive behavior.203

The frontal lobe comprises the largest portion of the brain, and the prefrontal cortex of the frontal lobe functions as the "chief executive officer" and controls most advanced cerebral functions.204 These "executive functions" include impulse control, reasoning, abstract thinking, imagining, planning behavior, and anticipating consequences.205 Brain maturation influences "affect regulation" and the ability to control emotions and behavior.206

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) studies provide cross-sectional images of the brain and enable neuroscientists to study longitudinal changes in brain structure and function.207 In the womb and during the first eighteen months of life, the human brain consists primarily of gray matter that is composed of neurons.208 A neuron is the basic nerve cell. Dendrites are branch-like protrusions from the neurons that receive electrochemical impulses from other nerve cell. Axons are transmitters to conduct electrochemical impulses from one neuron to the next.209 A process of myelination occurs in which the myelin, a fatty white substance, forms a sheath that surrounds and insulates the axons of certain neurons, gives it a white appearance, and allows for more rapid and efficient neurotransmission.210 The brain transmits information through electrochemical impulses and myelination functions like insulation and enhances the speed of the electrochemical impulse.211

Although the human brain attains its adult weight by early childhood, during the first two decades, it undergoes separate processes of dendritic pruning or loss, and grey matter conversion into white matter through myelination. "[C]ortical grey and cerebral white matter volumes are quite dynamic throughout childhood," with a loss of grey volume and a corresponding gain in white volume associated with age.212 The neural connections or synapses that the brain uses are retained, or etched for specific sensory, motor, and intellectual functions, and those that are not exercised are shed and discarded or "pruned.,213 During childhood and in early adolescence, the brain undergoes simultaneous processes of "pruning" and myelination.214 In early childhood, the portions of the brain that receive sensory input-the occipital and parietal lobes-myelinate initially to transmit sensory information more efficiently to the temporal and frontal lobes.215 During adolescence, the brain undergoes a second period of rapid "pruning" accompanied by further myelination.216 The separate and distinct processes of pruning and myelination are critical to proper brain function because dendritic pruning affects cognitive functioning and reasoning ability, while myelin insulation affects the rapidity and quality of brain activity.217 Because the process of myelination occurs approximately from the back of the brain to the front, the shift from gray matter to white matter in the frontal cortex and the corresponding abilities to process information quickly, to control behavior, and to suppress impulses develop more slowly, and maturation is completed only in the late teens and early twenties.218 As a result, the portions of the adolescent brain that mediate sensory input and language functions mature earlier than the portions in the frontal lobe governing "executive functioning" capacities.219

The part of the brain called the amygdala-the lymbic system located at the base of the brain-is responsible for instinctual or "gut reactions" such as "fight or flight."220 Functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals that teenagers rely more heavily than adults on the amygdala and less heavily on the prefrontal cortex when responding to stressful stimuli.221 Thus, adolescent reactions to fear-evoking stimuli appear to be more instinctual responses rather than the product of cognitive processes.222 One recent study of MRI imaging of adolescent brains reported that

[i]n regions of frontal cortex, we observed reduction in gray matter between adolescence and adulthood, probably reflecting increased myelination in peripheral regions of the cortex that may improve cognitive processing in adulthood.... Neuropsychological studies show that the frontal lobes are essential for such functions as response inhibition, emotional regulation, planning and organization. Many of these aptitudes continue to develop between adolescence and young adulthood.... Thus, observed regional patterns of static versus plastic maturational changes between adolescence and adulthood are consistent with cognitive development.223

Many adolescents' decisions about risky behavior appear to be more a function of "gut reactions" than of conscious thought processes.224 Just as organic features produce the developmental characteristics of mentally retarded defendants, similarly, the behaviors of adolescents may225 have a significant neurobiological component.

Although this section focuses primarily on deserved punishment and adolescents' reduced culpability, the Supreme Court in Atkins and Thompson noted that mentally retarded and younger offenders also were less susceptible than rational adult actors to the deterrent threat of capital punishment.226 Whether substantive changes in criminal law doctrines or liability produce any deterrent effect on criminal behavior remains controverted.227 However, all of the developmental characteristics that render adolescent offenders less culpable-- impaired judgment and reasoning, limited impulse control, and susceptibility to peer influences-- also reduce the likelihood that the threat of execution or draconian sentences will have any appreciable deterrent effect on younger offenders decisions to commit crimes.228

B. Atkins, Adolescents, and Adjudicative Competence

In addition to their reduced culpability, the Supreme Court in Atkins noted that the developmental disabilities of defendants with mental retardation also reduced their competence to stand trial and adversely affected the fairness and reliability of criminal proceedings.229 As states transfer more and younger offenders for adult prosecution, criminal courts increasingly encounter more youths whose immaturity and developmental limitations also pose difficult questions about their adjudicative competence.

In reaction to significant increases in the juvenile arrest rates for violent crimes in the late 1980s and early 1990s, virtually every state revised its transfer laws to prosecute more juveniles in criminal court.230 Changes in waiver statutes use offense criteria either as guidelines to control and limit judicial discretion, to guide prosecutorial charging decisions, or automatically to exclude serious offenses from juvenile court jurisdiction.231 Changes in waiver laws reflect a cultural and legal reconceptualization of youths from innocent and dependent children to responsible, adult-like offenders, and criminal sentencing laws typically provide no formal recognition of youthfulness once states transfer a juvenile to criminal court.232 When states try youths as adults, criminal court judges sentence them as if they are adults, imposing the same length sentences, sending them to the same prisons, and executing them for the crimes they committed as children.233

Waiver reforms that lower the age of transfer eligibility to fourteen years of age or even younger present criminal courts with many youths whose developmental immaturity, rather than-or in addition tomental illness, presents significant issues of adjudicative competence as well as diminished responsibility.234 The influx of more young juveniles into criminal courts raises questions about their ability to understand the trial process and to make critical legal decisions.235

Adjudicative competence refers to a person's ability to understand the nature and consequences of legal proceedings, to make decisions, and to assist counsel.236 A defendant must be able to understand the purpose of the trial process, to provide information to and process information from counsel, to reason appropriately, and realistically to apply that information to the legal situation she confronts.237 Competence is necessary to assure the legitimacy of the criminal process, to reduce the risk of erroneous convictions, and to protect the dignity and autonomy of the defendant.238 Because criminal courts employ a low standard of competence and threshold for criminal liability, recognizing the diminished responsibility of youth as grounds for mitigation of punishment becomes even more imperative.239

Typically, defendants' mental illness or developmental disability provides reasons to question their competence to stand trial and their ability to understand proceedings and to assist counsel.240 However, developmental immaturity also may render juveniles incompetent to stand trial.241 Juveniles' questionable competence does not derive necessarily from mental illness or disability, but rather from generic developmental limitations which affect their ability to communicate, to reason and understand, and to exercise judgment and make sound decisions. Although a relaxed standard of competence may be appropriate for delinquents tried in juvenile court, youths tried in criminal court must demonstrate an adult standard of competence.242

While competence focuses primarily on the ability to understand and reason, youths' immaturity of judgment also affects their decisionmaking capability. Research evaluating adolescents' and young adults' competence to participate in their trials found significant differences in understanding and judgment.243 Most youths younger than thirteen or fourteen years of age lacked even basic competence either to understand or to meaningfully participate in their defense.244 Many youths younger than sixteen years of age lacked competence either to stand trial as adults or to make legal decisions without the assistance of counsel, and many older youths exhibited substantial impairment.245 Moreover, youths' limited time-perspective, emphasis on short-term versus long-term consequences, and concerns about peer approval cause them to make immature decisions relative to those of adults.246 One recent study reported that:

[A]pproximately one fifth of 14- to 15-year-olds are as impaired in capacities relevant to adjudicative competence as are seriously mentally ill adults who would likely be considered incompetent to stand trial by clinicians who perform evaluations for courts.... Not surprisingly, juveniles of below-average intelligence are more likely than juveniles of average intelligence to be impaired in abilities relevant for competence to stand trial. Because a greater proportion of youths in the juvenile justice system than in the community are of below-average intelligence, the risk for incompetence to stand trial is therefore even greater.247

Atkins noted that the disabilities of mentally retarded defendants adversely affected their competence to stand trial, reduced the assistance they could provide to their lawyers, and impaired their demeanor and effectiveness as witnesses.248 Atkins also found that mental retardation exposed such defendants to the dangers of erroneous convictions because of their greater susceptibility to interrogation techniques and the concomitant dangers of false confessions.249 The same concerns about the dangers of erroneous convictions exist with respect to the competence of adolescents.250 Juveniles' diminished understanding of rights, confusion about trial processes, limited language skills, and inadequate decision-making abilities increase their vulnerability to interrogation tactics and their likelihood of giving false confessions.251

Juveniles are less able than adults to exercise their Miranda rights and exhibit a significant tendency to comply with authority, such as by confessing to police.252

When the Supreme Court in In re Gault applied the privilege against self incrimination to delinquency proceedings,253 the "warning" safeguards developed in Miranda v. Arizona254 became available to juveniles. Courts evaluate juveniles' waivers of Fifth Amendment rights and the voluntariness of any confessions by assessing whether the they made a "knowing, intelligent, and voluntary" waiver under the "totality of the circumstances.255 Even before Miranda and Gault, the Supreme Court had cautioned trial judges to closely scrutinize the impact of youthfulness and inexperience on the validity of waivers and the voluntariness and reliability of confessions.256 However, the Court in Fare v. Michael C. retreated from its earlier concern that youthfulness might increase suggestibility and vulnerability to coercion257 and endorsed the adult "totality of the circumstances" test as the standard by which to evaluate the admissibility of juvenile confessions.258 The "totality" approach provides trial judges with discretion to protect youths who lack capacity or who succumb to police coercion without unduly limiting police ability to interrogate juveniles.259

Fare declined to give children greater procedural protection than adults.260 Instead, the Court insisted that children must invoke their legal rights with adult-like technical precision and denied that young people lacked the ability to exercise or validly waive their rights.261 The Court explicitly rejected the view that developmental or psychological differences between juveniles and adults required different rules or special procedural protections during interrogation.262

Despite Fare's endorsement of the "totality" approach, reasons exist to question whether a typical juvenile can waive her rights in a "knowing, intelligent, and voluntary" manner. Evaluation studies indicate that most juveniles who receive a Miranda warning do not understand it well enough to exercise or waive their rights263 Juveniles most frequently misunderstood the advisory that they had the right to consult with an attorney and to have one present during interrogation.264 Younger juveniles exhibited even greater difficulties understanding their rights.

As a class, juveniles younger than fifteen years of age failed to meet both the absolute and relative (adult norm) standards for comprehension .... The vast majority of these juveniles misunderstood at least one of the four standard Miranda statements, and compared with adults, demonstrated significantly poorer comprehension of the nature and significance of the Miranda rights.265

Although younger juveniles exhibited significantly poorer comprehension than did comparable adults, the level of understanding by youths sixteen and older, although more similar to that of adults, left much to be desired.266 Even if juveniles abstractly understand the words of the Miranda warning, they may not appreciate the significance and function of their rights.267 Research conducted under laboratory conditions may fail to capture the social context and stressful conditions associated with actual police interrogation.268

Adolescents have difficulty grasping the basic concept of a "right"269 as an entitlement that they can exercise without adverse consequences. Children question whether law enforcement officials will punish them if they exercise their rights.270 Societal expectation of youthful obedience to authority and youths' inferior social status relative to adults render juveniles more vulnerable to police interrogation techniques.271 Many people from traditionally disempowered communities, such as females, African-Americans, and youth, pragmatically use indirect speech patterns to avoid conflict when dealing with authority figures.272 People with lower social status than their interrogators typically respond more passively, talk more readily, acquiesce to police suggestions more easily, and speak less assertively.273 Thus, Fare's requirement that youths invoke Miranda rights with adult-like precision contradicts the normal social reactions and verbal styles of most delinquents.

Juveniles' lack of understanding and vulnerability to coercion raise questions about the adequacy of the Miranda warning as a procedural safeguard to prevent youths from giving unreliable or false confessions.274 Deceptive interrogation techniques may be especially effective when employed against the young and inexperienced.275 Interrogation tactics such as presenting false evidence, using leading questions, and adopting police interpretations are more likely to induce juveniles to give false or inaccurate confessions than adults.276 The coercive context of interrogation and youths' limited understanding and verbal skills render young offenders more likely to comply with authority, to acquiesce in police interpretations, to fill in gaps through fabrication, to tell police what they think they want to hear, and to give unreliable and false confessions.277 Immaturity and suggestibility increase the likelihood of false confessions.278 Youths are also less able than adults to think strategically and to appreciate the consequences of admissions, and are more likely than adults to assume responsibility out of a misguided feeling of loyalty to peers.279 Aggressive questioning by police further increases the likelihood of false confessions, and instances abound of juveniles confessing to homicides and other serious crimes that they did not commit.280 Although younger offenders are at greatest risk, even older youths evidence a heightened risk of giving false confessions.281 Juveniles' lack of competence and vulnerability to coercive interrogation increase the risks of false confessions and erroneous convictions.

IV. YOUTH POLICY AND CRIME POLICY: CAPITAL PUNISHMENT AND LWOP SENTENCES

Youths' immature judgment, limited self-control, and inability to appreciate fully the consequences of their behavior reduce their degree of criminal responsibility and deserved punishment. While young offenders possess sufficient understanding and culpability to hold them accountable for their acts, their crimes are less blameworthy than those of adults, justifying a categorically different sentencing policy.282 Similarly, youths' diminished adjudicative competence increases the likelihood of false confessions and erroneous convictions. The Court's reasoning in Atkins and the analogous developmental limitations of adolescents should ban imposition of the death penalty. Penal proportionality and the reduced culpability of youth also should preclude sentences of Life Without Parole (LWOP) and even of lengths equivalent to those of adult offenders. As a matter of sentencing policy, there is no principled basis on which to distinguish between the diminished responsibility of youth that precludes the death penalty and the reduced culpability that warrants shorter sentences for all serious crimes.283 And, it is the reality of draconian sentences, rather than the risk of execution, that faces far more irresponsible young offenders.

The case of Lionel Tate graphically illustrates the hazards of disproportionality and adjudicative incompetence when states try young offenders as adults in criminal court. The grand jury indicted twelve-year-old Tate for first-degree murder for the brutal injuries he inflicted on a six-year-old girl.284 Under Florida's waiver law,285 Tate's indictment for a capital crime required the state to prosecute him as an adult, and his conviction of first degree murder required the judge to impose a mandatory sentence of life in prison without parole.286 The Florida Court of Appeals reversed his conviction, holding that the trial judge should have conducted a competency hearing to determine whether Tate understood the consequences of proceeding to trial and whether he was able to assist counsel prior to and during the trial.287 However, it rejected Tate's contention that imposing a mandatory LWOP sentence on a twelve-year-old child was disproportionate or constituted "cruel and unusual punishment."288

For two decades the Supreme Court has struggled with the question of whether the Eighth Amendment's prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment contains a "narrow proportionality principle" that "applies to noncapital sentences."289 The Court in Rummel v. Estelle290 held that it did not violate the Eighth Amendment for a State to sentence a three-time offender to life in prison with the possibility of parole.291 Subsequently, in Solem v. Helm292 the Court held that the Eighth Amendment prohibited a sentence of "life without possibility of parole" for a repeat offender convicted of a minor property crime.293 Solem identified three factors that a court must consider to determine whether a sentence is so disproportionate that it violates the Eighth Amendment: "(i) the gravity of the offense and the harshness of the penalty; (ii) the sentences imposed on other criminals in the same jurisdiction; and (iii) the sentences imposed for commission of the same crime in other jurisdictions."294 However, in Harmelin v. Michigan295 a fractured Court rejected a proportionality challenge and upheld a sentence of life without possibility of parole for a first-time offender convicted of a drug offense.296

In his concurrence in Harmelin, Justice Kennedy asserted that "[t]he Eighth Amendment proportionality principle also applies to noncapital sentences."297 His concurrence has emerged as the operative test for disproportionality and holds that the Eighth Amendment prohibits "only extreme sentences that are 'grossly disproportionate' to the crime."298 While conceding that the contours of the proportionality principle are unclear, Kennedy identified four factors-- the primacy of legislative judgments about penalties, the multiplicity of legitimate penal objectives, the limited role for federal oversight of state sentencing schemes, and the requirement that objective factors inform federal proportionality review-- to enable a court to determine whether a penalty is "grossly disproportionate."299 Recently, the Court in Ewing v. California300 upheld the imposition of a sentence of twenty-five years to life under California's "three-strike" sentencing statute for the theft of three golf clubs.301

Given the imprecision of the Supreme Court's interpretation of the proportionality principle in noncapital cases, courts have struggled with its application to LWOP sentences imposed on juvenile offenders.302 Although proportionality emphasizes the relationship between the seriousness of the crime and the sentence imposed, courts focus almost exclusively on the gravity of the crime rather than the culpability of the actor who caused the harm when they assess seriousness.303 In Harris v. Wright,304 Judge Alex Kozinski rejected Harris' Eighth Amendment challenge to a mandatory LWOP sentence imposed on a fifteen-year-old convicted of murder.305 Kozinski emphasized that proportionality analyses are strictly circumscribed to instances of "gross disproportionality"306 and insisted

Youth has no obvious bearing on this problem: If we can discern no clear line for adults, neither can we for youths. Accordingly, while capital punishment is unique and must be treated specially, mandatory life imprisonment without parole is, for young and old alike, only an outlying point on the continuum of prison sentences. Like any other prison sentence, it raises no inference of disproportionality when imposed on a murderer.307

By emphasizing only the gravity of the offense and the harm caused, rather than the culpability of the offender, courts engage in circular reasoning-serious crimes are serious-and thereby exclude considerations of moral blameworthiness from the proportionality inquiry.308

Although Stanford established sixteen as the minimum age at which states can impose the death penalty, for noncapital sentencing, the Court has not set any minimum age for imposing sentences of life without parole on younger offenders.309 Youthfulness may be a relevant factor, albeit not a controlling one, when courts assess culpability.310 However, courts only conduct proportionality analyses when sentences are "grossly disproportionate" to the seriousness of the crime rather than to the culpability of the criminal. They routinely uphold LWOP and other very lengthy sentences imposed on very young offenders and rebuff claims that youthfulness is a mitigating factor that should trump mandatory sentences.311 Indeed, for some perverse reasons, courts may treat youthfulness as an aggravating, rather than mitigating, factor.312

Although it reversed the trial court on competency grounds, the appellate court in Tate v. State "reject[ed] the argument that a life sentence without the possibility of parole is cruel or unusual punishment on a twelve-year-old child."313 In State v. Green,314 the North Carolina Supreme Court approved a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment imposed on a thirteen-year-old convicted of a first-degree sexual offense.315 The Green court noted that many states transfer very young offenders to criminal court for adult prosecution,316 that age is a factor that may be considered but is not dispositive "in determining whether a punishment is grossly disproportionate to the crime,"317 and that retribution and incapacitation are appropriate sentencing goals even for young offenders.318 In Hawkins v. Hargett,319 the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals approved sentences totaling 100 years for burglary, rape, and robbery imposed on a juvenile for crimes committed when he was thirteen years of age.320 State courts routinely approve sentences of life-- with or without possibility of parole-- or for extremely long periods of time imposed on thirteen-, fourteen-, or fifteen-year-old youths, whether those youths were convicted of murder or other crimes.321 Few courts ever invalidate lengthy sentences imposed on young offenders for being disproportional.322

A. Youthfulness as a Mitigating Factor in Sentencing

The Constitution does not require state legislatures to recognize or courts to implement a principle of youthfulness as a mitigating factor in sentencing except for the death penalty. The Court never has read the Eighth Amendment to preclude imposition of an LWOP sentence on a twelve-year-old. However, regardless of what the Constitution requires, state legislators and courts should explicitly adopt and apply such a principle as part of a fair and just youth sentencing policy. As a matter of crime policy, youths' developmentally diminished responsibility and limited adjudicative competence render them less culpable than adult offenders; as a matter of youth policy, adolescence is a period of rapid growth and transition, and youths are "works in progress" who have not yet become the people they will be as adults.323 Youths learn by doing, make mistakes as a by-product of gaining experience, and need protection from the worst consequences of their immature judgment.324 Youths have a different developmental trajectory from mentally retarded offenders, and with normal maturation they eventually can learn to act responsibly.

A youth and crime policy must manage the risks that youths pose to themselves and to others, and reduce the harm that the justice system inflicts on them as they make the transition to adulthood. A policy to preserve young people's life chances for the future when they will be able to make more responsible choices must protect them from the full penal consequences of their present poor decisions. It holds them accountable because they are somewhat culpable and yet mitigates the severity of sentences because their choices entail less blameworthiness than do those of adults.325

Penal proportionality dictates shorter sentences for youth because of diminished responsibility. While criminal law presumes autonomous choices by free-willed actors, adolescents have not yet acquired experience, self-control, and maturity of judgment to validate such a presumption. Even if a youth is criminally responsible for causing a particular harm, the law should not treat her choices as the moral equivalents of an adult's and impose the. same sentence.326 Political sound-bites---"Adult crime, adult time," or "Old enough to do the crime, old enough to do the time"-- provide simplistic answers to complex moral and legal questions.

Youths' normal tendency to make poor decisions reveals less about their subjective character and blameworthiness than do the criminal choices that adults make.327 Youth is a time of experimentation and exploration, and youths' character remains somewhat unformed and malleable.328 Like other forms of risky behavior, most adolescent criminality is transitional and normal, and does not indicate a serious commitment to a criminal career.329 Penal policy should recognize the rapidity and volatility of development during adolescence and avoid draconian sanctions.330

A protective youth policy would avoid life destructive consequences and provide young people with "room to reform."331 Youth is a period of "semi-autonomy," exploration, and risk taking and teenagers require a "learner's permit" to learn to make responsible choices without suffering fully for the consequences of their mistakes. The ability to make responsible choices is learned behavior and adolescence is the period during which youths learn to control their impulses and to exercise self-control.332 Unlike the defendants in Atkins, juveniles can learn to be responsible, and youth and crime policy should provide them with that opportunity.

A youth sentencing policy would impose shorter sentences than for older offenders simply because of juveniles' immaturity and diminished culpability. Youths' diminished responsibility has broader sentencing policy implications than just prohibiting their execution. Although the Court's proportionality analyses focus on the death penalty, the principle of youthful reduced culpability should mitigate the severity of all penalties-capital, LWOP, mandatory minimum, and sentence lengths. Formal mitigation of punishment based on youthfulness applies equally to capital and noncapital sentences and recognizes reduced culpability without excusing criminal conduct.333

Adolescents as a class characteristically make poorer choices than do adults because of normal physical, neurobiological, psychological, and developmental processes. As the Supreme Court repeatedly has recognized,

youth is more than a chronological fact. It is a time and condition of life when a person may be most susceptible to influence and to psychological damage. Our history is replete with laws and judicial recognition that minors, especially in their earlier years, generally are less mature and responsible than adults. Particularly "during the formative years of childhood and adolescence, minors often lack the experience, perspective, and judgment" expected of adults.334

A sentencing policy that recognizes this simple, developmental truism would protect young people from the full consequences of their bad decisions.335

B. Youthfulness as an Individualized or Categorical Mitigating Factor: The Virtue of Bright-lines