Abstract

Questions about the nature of normative and atypical development in adolescence have taken on special significance in the last few years, as scientists have begun to recast old portraits of adolescent behavior in the light of new knowledge about brain development. Adolescence is often a period of especially heightened vulnerability as a consequence of potential disjunctions between developing brain, behavioral and cognitive systems that mature along different timetables and under the control of both common and independent biological processes. Taken together, these developments reinforce the emerging understanding of adolescence as a critical or sensitive period for a reorganization of regulatory systems, a reorganization that is fraught with both risks and opportunities.

Introduction

Questions about the nature of normative and atypical development in adolescence have taken on special significance in the last few years, as scientists have begun to recast old portraits of adolescent behavior in the light of new knowledge about brain development. Adolescence is often a period of especially heightened vulnerability as a consequence of potential disjunctions between developing brain, behavioral and cognitive systems that mature along different timetables and under the control of both common and independent biological processes. Taken together, these developments reinforce the emerging understanding of adolescence as a critical or sensitive period for a reorganization of regulatory systems, a reorganization that is fraught with both risks and opportunities. Introduction Adolescence is characterized by an increased need to regulate affect and behavior in accordance with long-term goals and consequences, often at a distance from the adults who provided regulatory structure and guidance during childhood. Because developing brain, behavioral and cognitive systems mature at different rates and under the control of both common and independent biological processes, this period is often one of increased vulnerability and adjustment. Accordingly, normative development in adolescence can profitably be understood with respect to the coordination of emotional, intellectual and behavioral proclivities and capabilities, and psychopathology in adolescence may be reflective of difficulties in this coordination process.

The notion that adolescence is a heightened period of vulnerability specifically because of gaps between emotion, cognition and behavior has important implications for our understanding of many aspects of both normative and atypical development during this period of the life-span. With respect to normative development, for instance, this framework is helpful in understanding age differences in judgment and decision-making, in risktaking, and in sensation-seeking [1]. With respect to atypical development, the framework helps us to understand why adolescence can be a time of increased risk for the onset of a wide range of emotional and behavioral problems, including depression, violent delinquency and substance abuse [2].

Questions about the nature of normative and atypical development in adolescence have taken on special significance in the last few years as scientists have begun to recast old portraits of adolescent psychological development in light of new knowledge about adolescent brain development. Recent discoveries in the area of developmental neuroscience have stimulated widespread scientific and popular interest in the study of brain development during adolescence, as well as substantial speculation about the connections between brain maturation and adolescents’ behavioral and emotional development. Indeed, the topic has garnered such widespread public interest that it was the subject of a recent cover story in Time magazine aimed at parents of teenagers [3], and was raised in arguments submitted in late 2004 to the United States Supreme Court in connection with the Court’s consideration of the constitutionality of the juvenile death penalty [4].

Brain development in adolescence

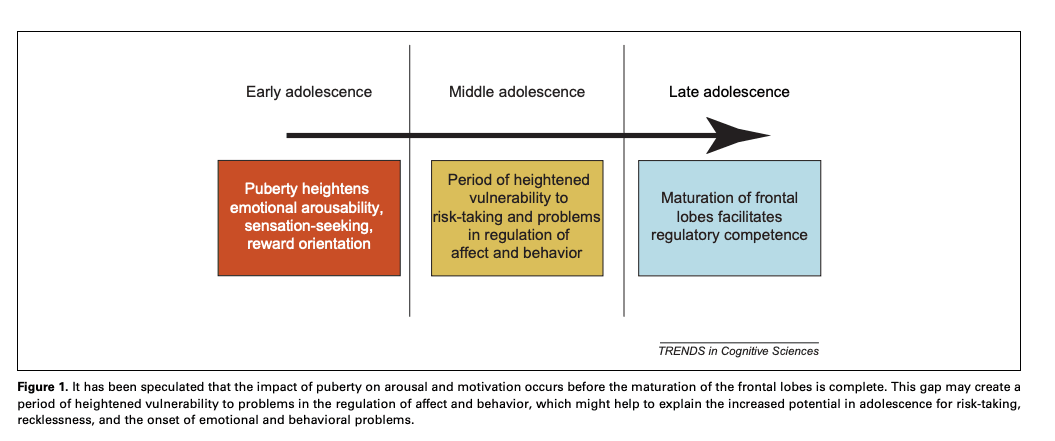

As reviewed in the accompanying article by Paus [5] there is growing evidence that maturational brain processes are continuing well through adolescence. Even relatively simple structural measures, such as the ratio of whiteto-gray matter in the brain, demonstrate large-scale changes into the late teen-age years [6–8]. The impact of this continued maturation on emotional, intellectual and behavioral development has yet to be thoroughly studied, but there is considerable evidence that the second decade of life is a period of great activity with respect to changes in brain structure and function, especially in regions and systems associated with response inhibition, the calibration of risk and reward, and emotion regulation. Contrary to earlier beliefs about brain maturation in adolescence, this activity is not limited to the early adolescent period, nor is it invariably linked to processes of pubertal maturation (Figure 1).

Two particular observations about brain development in adolescence are especially pertinent to our understanding of psychological development during this period. First, much brain development during adolescence is in the particular brain regions and systems that are key to the regulation of behavior and emotion and to the perception and evaluation of risk and reward. Second, it appears that changes in arousal and motivation brought on by pubertal maturation precede the development of regulatory competence in a manner that creates a disjunction between the adolescent’s affective experience and his or her ability to regulate arousal and motivation. To the extent that the changes in arousal and motivation precede the development of regulatory competence – a reasonable speculation, but one that has yet to be confirmed – the developments of early adolescence may well create a situation in which one is starting an engine without yet having a skilled driver behind the wheel [9].

Cognitive development in adolescence

Until recently, much of the work on adolescent cognitive development was devoted to a search for a core mechanism that could account parsimoniously for broad changes in adolescent thinking [10]. After nearly 50 years of searching, what has emerged instead is the necessity of an integrated account. What lies at the core of adolescent cognitive development is the attainment of a more fully conscious, self-directed and self-regulating mind [10]. This is achieved principally through the assembly of an advanced ‘executive suite’ of capabilities [11], rather than through specific advancement in any one of the constituent elements. This represents a major shift in prevailing views of adolescent cognition, going beyond the search for underlying elements [12] that are formed and operate largely outside awareness.

As Keating [10] has noted, the plausibility of such an integrative account has been substantially enhanced by recent major advances in the neurosciences [6–8,13–18], in comparative neuroanatomy across closely related primate species that illuminate core issues of human cognitive evolution [10,19], and in a deepened understanding of the critical role of culture and context in the shaping of cognitive and brain development [11,20]. Much of the underlying action is focused on specific developments in the prefrontal cortex, but with an equally significant role for rapidly expanding linkages to the whole brain [11,15,21]. This complex process of assembly is supported by increasingly rapid connectivity (through continued myelination of nerve fibers), particularly in communication among different brain regions, and by significant and localized synaptic pruning, especially in frontal areas that are crucial to executive functioning [6–8,18].

Whatever the underlying processes, during early adolescence, individuals show marked improvements in reasoning (especially deductive reasoning), information processing (in both efficiency and capacity), and expertise. These conclusions derive from studies of age differences in logical reasoning on tasks in which participants are asked to solve verbal analogies or analyze logical propositions; basic cognitive processes, such short- or long-term memory; and in specialized knowledge [10]. There has been broad consensus for more than 25 years that, as a result of these gains, individuals become more capable of abstract, multidimensional, planned and hypothetical thinking as they develop from late childhood into middle adolescence (less is known about cognitive changes during late adolescence). No research in the past several decades has challenge this conclusion.

Implications of new brain maturation research for adolescent cognitive development

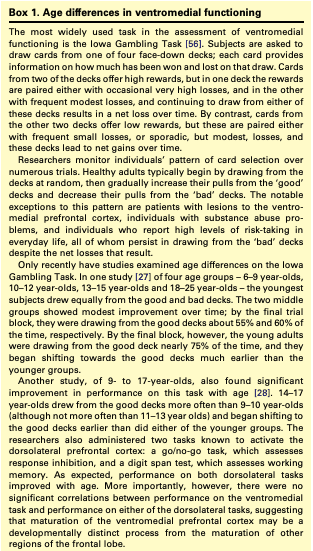

After a rather lengthy period during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the study of adolescent cognitive development was more or less moribund, interest in intellectual development during adolescence has been revitalized in recent years in two ways. First, researchers in the field of developmental neuroscience began to direct attention to the study of structural and functional aspects of brain development during early adolescence [6,8,13,22]. These studies have pointed both to significant growth and significant change in multiple regions of the prefrontal cortex throughout the course of adolescence, especially with respect to processes of myelination and synaptic pruning (both of which increase the efficiency of information processing) [8,17,23]. These changes are believed to undergird improvements in various aspects of executive functioning, including long-term planning, metacognition, self-evaluation, self-regulation and the coordination of affect and cognition [10]. Most research has focused on age differences in skills known to be related to functioning in the dorsolateral region of the prefrontal cortex, such as those involving working memory, spatial working memory and planning [24–26], but two recent studies [27,28] indicate as well that adolescence is a time of improvement in abilities that have been linked to functioning in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, such as the calibration of risk and reward (Box 1).

In addition, adolescence appears to be a time of improved connectivity between regions of the prefrontal cortex and several areas of the limbic system, a restructuring that further affects the ways in which individuals evaluate and respond to risk and reward [22,29]. Whether and to what extent these changes in brain structure and function are linked to processes of pubertal maturation is not known. Some aspects of brain development are coincident with, and likely linked to, neuroendocrinological changes occurring at the time of puberty, but others appear to take place along a different, and later, timetable. Disentangling the first set from the second is an important challenge for the field [9]. It is also important to note that there are relatively few studies of developmental changes in brain function (as opposed to structure) in adolescence, and that conclusions about the putative links between changes in cognitive performance and changes in brain structure during adolescence are suggestive, rather than conclusive.

Cognitive development in context

A second relatively new direction in research on adolescent cognitive development has involved the study of cognitive development as it plays out in its social context and, in particular, as it affects the development of judgment, decision-making and risk-taking [30–35]. New perspectives on adolescent cognition-in-context emphasize that adolescent thinking in the real world is a function of social and emotional, as well as cognitive, processes, and that a full account of the ways in which the intellectual changes of adolescence affect social and emotional development must examine the ways in which affect and cognition interact [10]. Studies of adolescents’ reasoning or problem-solving using laboratory-based measures of intellectual functioning might provide better understanding of adolescents’ potential competence than of their actual performance in everyday settings, where judgment and decision-making are likely affected by emotional states, social influences and expertise [1]. Thus, whereas studies of people’s responses to hypothetical dilemmas involving the perception and appraisal of risk show few reliable age differences after middle adolescence, studies of actual risk-taking (e.g. risky driving, unprotected sexual activity, etc.) indicate that adolescents are significantly more likely to make risky decisions than are adults.

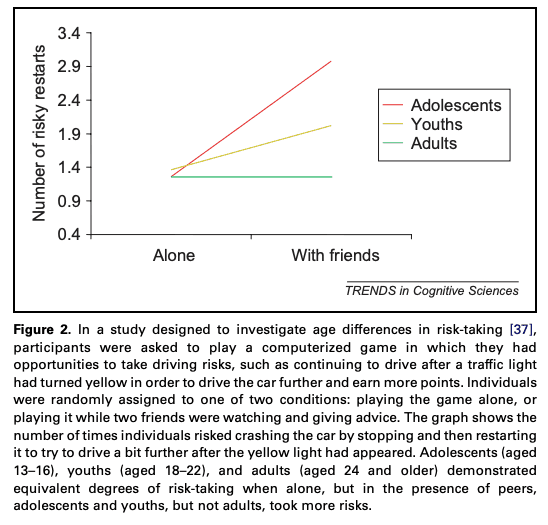

One reasonable hypothesis is that adults and adolescents 16 and older share the same logical competencies, but that age differences in social and emotional factors, such as susceptibility to peer influence or impulse control, lead to age differences in actual decision-making [36]. Research that examines developmental changes in cognitive abilities assessed under varying social and emotional conditions (e.g. the same task administered under conditions of high versus low affective arousal, or in the presence versus absence of peers) would be potentially quite informative, as at least one study indicates that adolescents’ risk taking is more influenced than that of adults by the presence of peers [37] (Figure 2).

Consistent with findings on the advances in reasoning, characteristic of the transition into adolescence, studies of social cognition demonstrate that the ways in which adolescents think about others becomes more abstract, more differentiated and more multidimensional [38]. More recent studies of changes in social cognition during adolescence have attempted to clarify the conditions under which relatively more advanced displays of social cognition are likely to be seen; to describe gender and cultural differences in certain aspects of social cognition, such as prosocial reasoning [39,40] or impression formation [41]; and to examine the links between social cognition and social behavior. These studies indicate that patterns of social cognitive development in adolescence, like patterns of cognitive development more generally, vary both as a function of the content under consideration and the emotional and social context in which the reasoning occurs [38].

For example, although individuals’ thinking about moral dilemmas becomes more principled over the course of adolescence, their reasoning about real-life problems is often not as advanced as their reasoning about hypothetical dilemmas [42]. The correlation between adolescents’ moral reasoning and their moral behavior is especially likely to break down when individuals define issues as personal choices rather than ethical dilemmas (for instance, when using drugs is seen as a personal matter rather than a moral issue) [43]. Similarly, when faced with a logical argument, adolescents are more likely to accept faulty reasoning or shaky evidence when they agree with the substance of the argument than when they do not [44,45]. And, although individuals’ ability to look at things from another person’s perspective increases in adolescence, the extent to which this advanced social perspective taking translates into tolerance for others’ viewpoints depends on the particular issue involved [46]. In other words, adolescents’ social reasoning, like that of adults, is influenced not only by their basic intellectual abilities, but by their desires, motives and interests.

Affect and cognition

In contrast to most measures of cognitive development in adolescence, which seem to correlate more closely with age and experience rather than the timing of pubertal maturation, there is evidence for a specific link between pubertal maturation and developmental changes in arousal, motivation and emotion. For example, there is evidence that pubertal development directly influences the development of romantic interest and sexual motivation [47,48]. There is also evidence that some changes in emotional intensity and reactivity, such as changes in the frequency and intensity of parent-adolescent conflict, may be more closely linked to pubertal maturation than to age [49]. Some cognitive skills related to human face-processing have also shown intriguing alterations in midadolescence – an apparent decrement in face processing skills that is associated with sexual maturation (measured by Tanner staging by physical examinations) rather than with age or grade level [50]. A parallel finding has been reported for voice recognition [51].

There is also evidence that increases in sensationseeking, risk-taking and reckless behavior in adolescence are influenced by puberty and not chronological age. For example, in a study by Martin et al. [29], where sensation-seeking and risk behaviors were examined in a large group of young adolescents aged 11 to 14, there was no significant correlation between age and sensation-seeking, but a significant correlation between sensation-seeking and pubertal stage. There is also evidence in animal and human studies supporting a link between increasing levels of reproductive hormones and sensitivity to social status [52,53], which is consistent with the link between puberty and risk-taking, since several influential theories of adolescent risk-taking [54] suggest that at least some of this behavior is done in the service of enhancing one’s standing with peers. Although further research is much needed, it appears that there are important links between pubertal maturation and social information-processing.

In some models of the development of affect regulation there is an explicit emphasis on cognitive systems exerting control over emotions and emotion-related behavior [55]. Many aspects of affect regulation involve the ability to inhibit, delay or modify an emotion or its expression in accordance with some rules, goals or strategies, or to avoid learned negative consequences. However, there is increasing understanding that cognitive-emotional interactions in adolescence also unfold in the other direction in important ways. Thus, just as cognition has an important impact on emotion, emotion has an important impact on basic cognitive processes, including decision-making and behavioral choice.

Decision-making and risk-taking

Behavioral data have often made it appear that adolescents are poor decision-makers (i.e. their high-rates of participation in dangerous activities, automobile accidents, drug use and unprotected sex). This led initially to hypotheses that adolescents had poor cognitive skills relevant to decision-making or that information about consequences of risky behavior may have been unclear to them [56,57]. In contrast to those accounts, however, there is substantial evidence that adolescents engage in dangerous activities despite knowing and understanding the risks involved [29,58,59,60–63]. Thus, in real-life situations, adolescents do not simply rationally weigh the relative risks and consequences of their behavior – their actions are largely influenced by feelings and social influences [1].

In contrast to much previous work on adolescent decision-making that emphasized cognitive processes and mainly ignored affective ones, there is now increasing recognition of the importance of emotion in decisionmaking [64]. The ‘decision’ to engage in a specific behavior with long-term health consequences – such as smoking a cigarette, drinking alcohol, or engaging in unprotected sex – cannot be completely understood within the framework of ‘cold’ cognitive processes. (‘Cold’ cognition refers to thinking processes under conditions of low emotion and/or arousal whereas ‘hot’ cognition refers to thinking under conditions of strong feelings or high arousal and which therefore may be much more important to understanding risky choices in real-life situations.) These affective influences are relevant in many day-to-day ‘decisions’ that are made at the level of ‘gut-feelings’ regarding what to do in a particular situation (rather than deliberate thoughts about outcome probabilities or risk value). These ‘gut feelings’ appear to be the products of affective systems in the brain that are performing computations that are largely outside conscious awareness [65,66]. How these feelings develop, become calibrated during maturation, and are influenced by particular types of experiences at particular points in development are only beginning to be studied within the framework of affective neuroscience [29]. It does, however, appear that puberty and sexual maturation have important influences on at least some aspects of affective influences on behavior through new drives, motivations and intensity of feelings, as well as new experiences that evoke strong feelings (such as developing romantic involvement) [67,68].

The development of regulatory competence

During the adolescent transition, regulatory systems are gradually brought under the control of central executive functions, with a special focus on the interface of cognition and emotion. Two important observations are especially important. The first is that the development of an integrated and consciously controlled ‘executive suite’ of regulatory capacities is a lengthy process. Yet, adolescents confront major, emotionally laden life dilemmas from a relatively early age – an age that has become progressively younger over historic time due to the decline in the age of pubertal onset and in the age at which a wide range of choices are thrust upon young people, as well as a decline in the active monitoring of adolescents by parents as a result of changes in family composition and labor force participation.

The second observation is that the acquisition of a fully coordinated and controlled set of executive functions occurs relatively later in development [10]. As such, it is less likely to be canalized (to the same degree as, say, early language acquisition), leaving greater opportunities for suboptimal trajectories. These suboptimal patterns of development take many different forms, clusters of which are associated with broad categories of psychopathology, such as the excessive down-regulation of mood and motivation that characterizes many internalizing difficulties, or the inadequate control of arousal that is associated with a wide range of risky behaviors typically seen as externalizing problems.

Concluding comments

Like early childhood, adolescence may well be a sensitive or critical developmental period for both normative and maladaptive patterns of development [69–71]. Several aspects of development during this period are especially significant in this regard, among them: the role of puberty in a fundamental restructuring of many body systems and as an influence on social information-processing; the apparent concentration of changes in the adolescent brain in the prefrontal cortex (which serves as a governor of cognition and action) together with the enhanced interregional communication between the prefrontal cortex and other brain regions; and the evidence for substantial synaptic pruning and for non-trivial physiological reversibility of behavioral and neuroendocrine patterns arising from early developmental experiences. Taken together, these developments reinforce the emerging understanding of adolescence as a critical or sensitive period for a reorganization of regulatory systems, a reorganization that is fraught with both risks and opportunities [10]. As we look to the future of research on cognitive and affective development in adolescence, the challenge facing researchers will be integrating research on psychological, neuropsychological and neurobiological development. What we now have are interesting pieces of a complicated puzzle, but the pieces have yet to be fit together in a way that moves the field out of the realm of speculation and towards some measure of certainty.