Abstract

Low-income children caught up in their parents’ economic struggles experience the impact through unmet needs, low-quality schools, and unstable circumstances. Children as a group are disproportionately poor: roughly one in five live in poverty compared with one in eight adults (US Census Bureau 2014).

Introduction

Low-income children caught up in their parents’ economic struggles experience the impact through unmet needs, low-quality schools, and unstable circumstances. Children as a group are disproportionately poor: roughly one in five live in poverty compared with one in eight adults (US Census Bureau 2014).

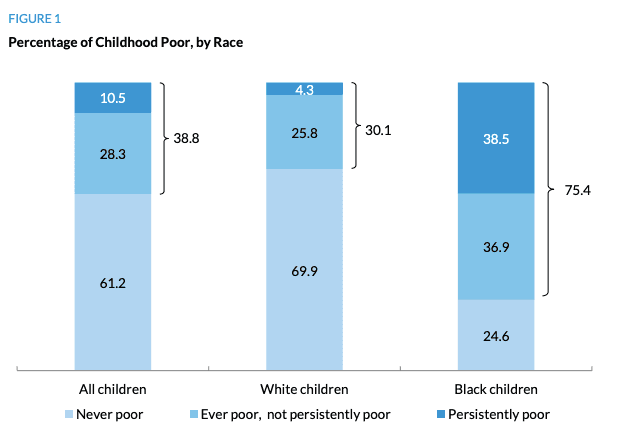

What does the long-term picture look like for children? How does it look for ever-poor children— those who are poor for at least one year before their 18th birthday? Following children from birth through age 17 shows a much greater prevalence of poverty than the annual figures would suggest. Four of every 10 children (38.8 percent) are poor for at least one year before they reach their 18th birthday (figure 1). Black children fare much worse: fully three-quarters (75.4 percent) are poor during childhood. The number for white children is substantial, yet considerably lower (30.1 percent).

Persistent childhood poverty—living below the federal poverty level for at least half of one’s childhood—is also prevalent, particularly among black children.1 Among all children, 1 in 10 (10.5 percent) is persistently poor. For black children this number is roughly 4 in 10 (38.5 percent), and for white children it’s fewer than 1 in 10 children (4.3 percent).2 Many of these children struggle academically, do not complete high school, and have spotty employment as young adults (Ratcliffe and McKernan 2010, 2012). But not all poor children have poor young adult outcomes. Two important questions are why some children succeed and what factors seem to help them do so (or at least do not hold them back).

Figure 1

Source: Author’s tabulation of PSID data.

Notes: Tabulations are weighted and include children born between 1968 and 1989. Persistently poor children are poor at least half the years from birth through age 17. Ever-poor, nonpersistently children are poor at least one year, but less than half the years, from birth through age 17.

The analysis begins by looking at all children but then narrows to concentrate on ever-poor children. Regression models examine how childhood experiences and family and neighborhood characteristics relate to children’s adult success as measured by completing high school by age 20, enrolling in postsecondary education (college or certificate program) by age 25, completing a four-year college degree by age 25, and being consistently employed in young adulthood (ages 25 through 30). Potential impediments to educational achievement and employment, specifically teenage nonmarital childbearing and involvement in the criminal justice system (as measured by being arrested by age 20) are also examined. These analyses are based on over 40 years of data (1968–2009) from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). The findings suggest the following:

The future achievement of ever-poor children is related to the length of time they live in poverty. Persistently poor children are 13 percent less likely to complete high school and 43 percent less likely to complete college than those who are poor but not persistently poor as children.

Parental education is closely related to the academic achievement of ever-poor children. Compared with ever-poor children whose parents do not have a high school education, everpoor children whose parents have a high school education or more than a high school education are 11 and 30 percent, respectively, more likely to complete high school.

Residential instability is related to lower academic achievement for ever-poor children. Everpoor children who move three or more times for negative reasons before they turn 18 are 15 percent less likely to complete high school, 36 percent less likely to enroll in college or another postsecondary education program by age 25, and 68 percent less likely to complete a four-year college degree by age 25 than ever-poor children who never move.

Living in a multigenerational household does not improve outcomes for ever-poor children. However, persistently poor children in multigenerational households are more likely to complete high school, enroll in postsecondary education, and complete college.

What Matters for Children?

Adult achievement is related to childhood poverty and the length of time they live in poverty. Children who are poor are less likely to achieve important adult milestones, such as graduating from high school and enrolling in and completing college, than children who are never poor. For example, although more than 9 in 10 never-poor children (92.7 percent) complete high school, only 3 in 4 ever-poor children (77.9 percent) do so (table 1).

Table 1

Educational Achievement, Employment, Nonmarital Childbearing, and Criminal Justice Involvement by Childhood Poverty Status (percent)

Among Ever Poor | Among Ever Poor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Never Poor | Ever Poor | Not Persistently Poor | Persistently Poor | |

Educational Attainment | ||||

High school diploma by age 20 | 92.7 | 77.9*** | 83.3 | 63.5*** |

Postsecondary enrollment by age 25 | 69.7 | 41.4*** | 47.6 | 22.8*** |

Completed college by age 25 | 36.5 | 13.0*** | 16.2 | 3.2*** |

Consistently employed ages 25–30 | 70.3 | 57.3*** | 63.6 | 35.4*** |

No premarital teen birth | 96.0 | 78.0*** | 83.0 | 64.4*** |

Never arrested by age 20 | 84.2 | 76.3** | 74.8 | 81.5 |

Source: Author’s tabulation of PSID data.

Notes: Tabulations are weighted and include children born between 1968 and 1989. Statistical significance for the “never poor” and “ever poor” data columns is based on the difference between individuals who are never poor and those who are ever poor in childhood. Significance for the “not persistently poor” and “persistently poor” data columns is based on the difference between individuals who are ever poor but not persistently poor and those who are persistently poor in childhood. *p < 0.1 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

When looking at the subset of children who experience poverty (i.e., ever-poor children), large differences emerge between children who are and are not persistently poor. Specifically, academic achievement, employment, and the likelihood of no teen childbearing are lower for persistently poor children than for nonpersistently poor children. Although 64 percent of persistently poor children complete high school, 83 percent of nonpersistently poor children do so—a difference of roughly 20 percentage points.

Time spent living in poverty matters even after controlling for a host of family- and neighborhood level (i.e., census tract) characteristics in regression models. These models also include race/ethnicity, gender, parental educational attainment at birth, whether and the number of times the family moves for a negative reason (e.g., housing unit coming down, being evicted, divorce, to pay lower rent),3 and mother’s age at birth, as well as the percentage of childhood spent living in a female-headed family, a multigenerational family, a disabled-headed family, a metropolitan area, and the South. A neighborhood disadvantage index, generated using neighborhood characteristics from US Census Bureau data (e.g., poverty rate, unemployment rate), is also included in the models (see data and methods box on pages 11–12). The findings discussed below, which are based on these regression models, examine ever-poor children and focus on identifying characteristics that are associated with better outcomes.4

Results from the regression models show that persistently poor children have less academic success than their counterparts who experience poverty but are not persistently poor. Specifically, persistently poor children are 13 percent less likely to complete high school by age 20, 29 percent less likely to enroll in postsecondary education by age 25, and 43 percent less likely to complete a four-year college degree by age 25 (table 2). These differences are large and show the substantial disadvantage for children from persistently poor families.

Persistently poor children are also less likely (by 37 percent) to be consistently employed as young adults than their ever-poor, nonpersistently poor counterparts. This finding is consistent with the lower educational achievement of the persistently poor and the fact that unemployment rates have historically been higher among lower-educated groups (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2014).

Two additional outcomes that can be a precursor to lower adult achievement are having a teen nonmarital birth (girls only) and involvement in the criminal justice system. Among ever-poor children, persistently poor children are not significantly more likely than nonpersistently poor children to have a teen nonmarital birth or be arrested by age 20. Looking at more specific breakdowns of childhood poverty duration, girls who are poor less than a quarter of their childhood are less likely to have a teen birth than girls who are poor more than a quarter of their childhood. This type of difference by poverty duration does not exist for arrest rates.

Overall, these statistics show that children who have a long and persistent exposure to poverty are disadvantaged in their educational achievement and employment.

Table 2

Relationship between Family Characteristics and Adult Achievement among Ever-Poor Children (percentage change)

Graduated high school by age 20 | Enrolled in postsecondary education by age 25 | Completed college by age 25 | Consistently employed ages 25–30 | No teen premarital births | No arrests by age 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Persistently poor (omitted: not persistently poor) | -12.6*** | -29.0*** | -42.5* | -36.6*** | -1.2 | 8.2 |

Parental education at birth (omitted: less than high school) | ||||||

High school education only | 11.0** | 59.9*** | 86.4 | -2.9 | 6.0 | -10.8 |

More than high school education | 30.1*** | 123.6*** | 384.1*** | 22.5 | 22.2*** | 5.0 |

Residential moves (omitted: never move) | ||||||

One negative move | -8.6 | -27.0** | -29.8 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 5.3 |

Two negative moves | -13.4** | -35.2*** | -60.2** | 2.5 | -15.1 | -10.1 |

Three or more negative moves | -15.2** | -36.1*** | -67.5** | -24.3 | -15.4* | -0.5 |

Positive or neutral move | -4.2 | -15.9 | -9.6 | 20.1 | -5.8 | -0.8 |

Family structure through age 17 (percent of years) | ||||||

Female-headed family | 3.8 | 13.5 | 28.3 | 8.5 | 1.7 | -9.8 ** |

Multigenerational family | -6.6 | -7.3 | -16.4 | -2.6 | 6.6 | 1.1 |

Disabled family head through age 17 (percent of years) | -5.5 | -10.5 | 25.0 | -20.6** | -10.3 | -19.2*** |

Race (omitted: white, non-Hispanic) | ||||||

Black, non-Hispanic | 1.2 | 10.1 | 25.8 | 5.5 | -9.8* | -2.0 |

Hispanic | 11.3 | 2.0 | -47.1 | 33.6 | -9.5 | — a |

Metropolitan area through age 17 (percent of years) | -5.3** | 0.5 | 17.8 | 3.5 | -2.5 | 3.4 |

South through age 17 (percent of years) | -0.0 | -2.5 | 22.7* | 2.5 | 0.1 | -1.2 |

Female (omitted: male) | 13.1*** | 29.1*** | 110.0*** | -26.0*** | — a | 23.5*** |

Mother’s age at birth (omitted: ages 20–29) | ||||||

Less than 20 | 3.8 | 19.0 | -16.8 | -9.5 | -6.2 | -9.3 |

30+ | 4.2 | 29.0** | 13.7 | 10.8 | -0.5 | -0.1 |

Neighborhood disadvantage index through age 17 (average) | -27.8* | -45.3 | -99.2*** | -11.9 | -55.2** | 43.5 |

Source: Author’s calculations from PSID, US Decennial Census, and American Community Survey data.

Notes: Results are based on probit models estimated on a sample of children born between 1968 and 1989. For indicator variables, the percentage change in the outcome variable is the difference in the predicted probability of the outcome with a particular characteristic (e.g., parents have high school education) versus the base category (e.g., parents have less than high school education) divided by the predicted probability of the outcome with the base category. The percentage change for the continuous variables is the difference between experiencing the characteristic for half versus none of childhood. The percentage change for the neighborhood disadvantage index is from the most advantaged neighborhood (index of -1.7) to the most disadvantaged neighborhood (index of 4.2). The model also includes controls for other non-Hispanic race, residential move for unknown reason, and birth cohort. aThe sample for the arrest model includes only whites and black non-Hispanics. It relates to the small subset of people asked about arrests (people born 1985 through 1989). The premarital birth model includes only females, so the female indicator does not apply. *p < 0.1 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

Parental education at the child’s birth is importantly related to children’s academic achievement, with lower educational attainment among children with less educated parents. 5 This relationship persists even after controlling for family and neighborhood characteristics, including childhood poverty. Compared with ever-poor children whose parents did not complete high school, children whose parents have more than a high school education are 30 percent more likely to complete high school, more than twice as likely to enroll in postsecondary education by age 25, and nearly five times more likely to complete college by age 25 (table 2). These individuals are also more likely to enter their twenties without having a nonmarital birth.

The relationships differ somewhat for children whose parents have only a high school education. Ever-poor children whose parents have a high school education (versus not completing high school) are more likely to complete high school and enroll in college or another postsecondary program (by 11 and 60 percent, respectively), but they are not statistically significantly more likely to complete a four-year college degree.6 That is, they are more likely to get some post–high school education but not get through a four-year college program.

The analysis does not suggest that parents’ educational attainment is related to whether a child is arrested during adolescence or whether he or she is consistently employed as a young adult. There is more to the story, however. Although no direct relationship with employment is found, it is well established that lower educational achievement brings lower wages on average and dampened opportunities for upward mobility (Greenstone et al. 2013; US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015).

Residential instability is related to lower academic achievement for ever-poor children, in both high school and college completion. Ever-poor children who move for a negative reason are worse off educationally than ever-poor children who never move. A consistent negative relationship appears for children who move twice and three or more times. Focusing on multiple childhood moves, the results show lower academic achievement across the board. Children with two or more negative moves are 13 to 15 percent less likely to complete high school, 35 to 36 percent less likely to enroll in postsecondary education, and 60 to 68 percent less likely to complete college than children who never move. Children with multiple negative moves also have worse educational outcomes than children who move for positive or neutral reasons.

Moves that happen for a negative reason can exacerbate already tenuous circumstances for children, particularly if the moves do not coincide with changes in the school year or promotional moves (e.g., from elementary to middle school). These results are consistent with research that finds children with multiple school moves are less likely to complete high school (Hartmann and Leff 2002; Rumberger and Larson 1998) and enroll in postsecondary school (Sandefur, Meier, and Campbell 2006).7

The results do not suggest any statistically significant differences between children who move for positive or neutral reasons and children who never move.

Only one statistically significant relationship is found among the other three outcomes (teen birth, employment, and arrest). Girls who move three or more times for negative reasons during childhood are 15 percent less likely than girls who never move to be childless throughout their teens. The results suggest no relationship between residential moves and the likelihood of being consistently employed as a young adult or being arrested by age 20.

The family structure of ever-poor children is generally unrelated to their achievement once family and neighborhood characteristics are controlled for. Living in a female-headed household for more years as a child is not related to educational achievement, employment, or teen childbearing. It is, however, related to the likelihood of being arrested. For example, spending half versus none of one’s childhood in a female-headed household is associated with a 10 percent decrease in the likelihood of not being arrested by age 20. When it comes to living in a multigenerational household (e.g., child, parent or parents, and grandparent), the analysis provides no evidence that this family structure improves the outcomes of ever-poor children.

A different pattern emerges, however, among persistently poor children. The longer a persistently poor child lives in a female-headed household, the less likely he or she is to complete high school. Also, living in a multigenerational household is associated with better educational achievement, offsetting some negative elements for children living in a female-headed household.8 Specifically, persistently poor children who spend half their childhood living in a female-headed family are 12 percent less likely to complete high school than their persistently poor counterparts who never live in a female-headed family (not shown). But persistently poor children who spend half their childhood living in a multigenerational family are 22 percent more likely to complete high school than their persistently poor counterparts who never live in a multigenerational family.

Although the literature on the implications of living in a multigenerational household is mixed, this analysis is consistent with several studies that find better academic and behavioral outcomes among children in multigenerational households (DeLeire and Kalil 2002; Entwisle and Alexander 1996; Pittman 2007). Improvements could result from a more structured environment that provides additional supervision, guidance, and/or help with studies. Other research, however, finds either no relationship or a negative one between children’s outcomes and living in a multigenerational household (Chase-Lansdale, Brooks-Gunn, and Zamsky 1994; Foster and Kalil 2007). These results could stem from differences in parenting approaches and increased family conflict (Augustine and Raley 2012; Bentley et al. 1999; Brooks-Gunn and Chase-Lansdale 1991).

Living in a multigenerational household is also associated with an increased likelihood that persistently poor children enroll in and complete college. Persistently poor children who spend half their childhood living in a multigenerational family are nearly twice as likely to enroll in postsecondary education and more than three times as likely to complete a four-year college degree as their counterparts who never live in a multigenerational family.

So, although the results suggest a limited relationship between family structure as a child and educational achievement for ever-poor children, there is some evidence that family structure is related to education outcomes for persistently poor children.

Ever-poor children who live with a disabled household head have some worse outcomes. The longer an ever-poor child lives in a household headed by someone with a disability, the less likely he or she is to be consistently employed as an adult. Children who live with a disabled household head are also more likely to be arrested by age 20. Risky behaviors among teens could stem from less supervision for them. The analysis suggests no relationship between years spent with a disabled household head and educational achievement or teen nonmarital childbearing.

The race and ethnicity of ever-poor children are largely unrelated to adult achievement once family and neighborhood characteristics are controlled for. One exception is that ever-poor black girls are less likely to be childless during their teens than ever-poor white non-Hispanic girls. This finding is consistent with the fact that the teen nonmarital birth rate is substantially higher for black women than white or Hispanic women (Martin et al. 2015).9 However, there could be differences in the level of disadvantage by race (e.g., greater disadvantage among poor black children) that these models do not capture and that could help account for the racial differences. Interestingly, a separate analysis of never-poor children finds no statistically significant difference in teen nonmarital childbearing by race.

Ever-poor girls fare much better than ever-poor boys. Across the board, ever-poor women have better educational outcomes and are less likely to be involved in the criminal justice system. Women in their late twenties, however, have lower employment rates, which could result from childbearing decisions.

Place and neighborhood characteristics matter for ever-poor children, even in models that control for childhood poverty status and multiple family characteristics. Ever-poor children who spend half their childhood living in a metropolitan area are 5 percent less likely to complete high school than their counterparts who never live in a metropolitan area.

The analysis also includes a measure of neighborhood (census tract) health that combines six characteristics: unemployment rate, poverty rate, property vacancy rate, percentage living in public housing, percentage living in a single parent–headed household with children, and percentage of adult population with less than a high school education. This neighborhood health measure is generated using factor analysis and ranges from -1.7 to 4.2. Lower values indicate greater neighborhood health, and higher values indicate worse health. At the lower end of the scale, neighborhood poverty and unemployment rates are below 5 percent. At the high end of the scale, poverty rates top 50 percent and unemployment rates are upward of 25 percent.

Children who grow up in more disadvantaged neighborhoods fare much worse. Compared with children in the most advantaged neighborhoods, children in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods are 28 percent less likely to complete high school and a staggering 99 percent less likely to complete a four year college degree. This result is consistent with research that finds students from neighborhoods with lower incomes and educational attainment are less likely to earn bachelor’s degrees (Owens 2010), which could result from weaker college preparation and/or fewer resources to complete college. Research also suggests greater college enrollment is associated with high school characteristics that more likely exist in better neighborhoods, such as higher teacher expectations, social norms around attending college, and greater staff support for college enrollment (Roderick, Coca, and Nagaoka 2011). The results also suggest that girls in more disadvantaged neighborhoods are less likely to be childless throughout their teens.

Summary and Implications

One in every five children currently lives in poverty, but nearly twice as many experience poverty at some point during their childhood. These ever-poor children are less successful than their never-poor counterparts in their educational achievement and employment, and they are more likely to have a nonmarital teenage birth and some involvement with the criminal justice system. Children who spend half their childhood living in poverty fall even further behind. For example, although 93 percent of never-poor children complete high school, and 83 percent of ever-poor, nonpersistently poor children complete high school, only 64 percent of persistently poor children do so. A large deficit exists even after controlling for other family and neighborhood characteristics. This disadvantage can erode employment prospects and wages throughout a lifetime.

The educational achievement of one generation can also ripple through to the next. The results suggest parental education relates to children’s academic achievement, even after controlling for other family and neighborhood characteristics. For example, ever-poor children whose parents have more than a high school education are 30 percent more likely to complete high school and almost five times more likely to complete college than ever-poor children whose parents did not complete high school.

Beyond childhood poverty experience and parental education, residential stability or instability stands out as important to children’s future success. Household moves that happen for negative reasons are particularly associated with worse outcomes. Ever-poor children with three or more negative moves (versus no moves) during their childhood, for example, are 15 percent less likely to complete high school by age 20, 36 percent less likely to enroll in college or another postsecondary education program by age 25, and 68 percent less likely to complete a four-year college degree by age 25. These outcomes could result not only from instability and uncertainty of circumstances within the household but also from changing schools; children with frequent school changes have lower educational achievement (Hartmann and Leff 2002; Sandefur, Meier, and Campbell 2006).

This research set out to find characteristics of ever-poor children and their families that relate to successful adult outcomes in order to identify steps for improving children’s outcomes. It highlights the importance of parental education and childhood residential stability and the potential benefits for persistently poor children of living in a multigenerational household.

Education and training programs, bundled with work supports such as child care subsidies, could improve financial well-being and stability for parents with limited education. Higher educational achievement has been clearly linked with higher employment rates and earnings (Baum 2014; Card 2001; US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015), and receipt of child care assistance has been found to increase the economic well-being of low-wage unmarried mothers (Acs, Loprest, and Ratcliffe 2010). The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, signed into law in July 2014, is an important step; it encourages states to provide better work supports, such as child care, to people in education and training programs and specifies low-income single parents as a group with particular need (Spaulding 2015).

Flexible policies that allow children to stay in the same school when a move takes them across school boundary lines could help children and the communities they live in when they complete school and enter the workforce. Federal policy targets some vulnerable populations (such as homeless and foster care children), allowing them to remain in the same school, but most low-income children are left out. With a focus on restricted populations, school districts face challenges identifying eligible children and have adopted different strategies for identifying homeless children, including working with local social service providers and community organizations and developing interagency working groups (Comey, Litschwartz, and Pettit 2012). Taking steps to provide stability for parents and children today could improve the outcomes of the next generation.

Data and Methods

Data and Sample: This analysis uses data from the 1968 through 2009 waves of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a longitudinal survey that interviewed respondents annually from 1968 through 1997 and biennially thereafter. This study focuses on people born between 1968 and 1989. Using data over 40 years allows individuals’ childhood experiences to be linked with their adult outcomes. White and black children are separately examined; there is not sufficient sample size to separately examine Hispanic children.a

Six outcome measures that capture success in young adulthood are examined: complete high school by age 20, enroll in postsecondary education by age 25, complete a four-year college degree by age 25, be consistently employed in early adulthood (ages 25 through 30), have no teen nonmarital birth, and have no arrest by age 20.

Given the available data and the different ages for the outcomes, sample sizes vary by outcomes. High school completion and teenage childbearing are available for the full study sample (people born from 1967 through 1989), postsecondary enrollment and college completion by age 25 are available for people born from 1967 through 1984, and consistent employment between ages 25 and 30 is available for people born from 1967 through 1979.b Information on arrests is available in the PSID Transition to Adulthood supplement, which is only available for people in our sample who were born from 1985 through 1989.c

Using PSID restricted geo-coded data, the main PSID file is augmented with census tract–level information from the US Census Bureau. Census tract–level variables include the unemployment rate, poverty rate, property vacancy rate, percentage living in public housing, percentage living in a single parent–headed household with children, and percentage of adult population with less than a high school education. d

At each interview, family annual income, which is used to construct family poverty status, is collected for the prior calendar year.e When the PSID shifted to biennial interviewing, it began collecting income data for each of the two prior years. However, a PSID technical paper cautions users about the quality of the income data from two years ago (Andreski, Stafford, and Yeung 2008), so these data are not incorporated into this analysis.

All the analyses presented here use the official definition of poverty. Under the official definition, a family is poor if its gross annual money income is below the federal poverty level. f In 2015, the federal poverty level for a family of three is $20,090. A strength of the official poverty measure is that it allows for straightforward comparisons over time. A child is persistently poor if he or she lives in a poor family for at least half his or her childhood (from birth through age 17).g

Regression Models: The regression models focus on children who were ever poor, with some analyses estimated on the subset of persistently poor children. Separate regression equations (weighted) are estimated for each of the six outcomes. The models include an indicator of whether the person was persistently poor as a child; race and ethnicity, gender, and parental educational attainment at birth; indicators for the number of times the family moved for a negative reason;h mother’s age at birth; percentage of years (from birth through age 17) spent living in a female-headed family, in a family with a disabled head, in a metropolitan area, or in the South; a factor designed to capture the relative health and strength of the neighborhood(s) (census tract) the child grew up in; and an indicator of birth cohort.

Factor analysis is used to create the neighborhood health measure. This measure is generated from the six neighborhood characteristics mentioned earlier (poverty rate, unemployment rate, property vacancy rate, percentage living in public housing, percentage living in a single parent–headed household with children, and percentage of adult population with less than a high school education).i Values range from -1.7 to 4.2, with lower values indicating greater health and higher values indicating worse health. At the lower end of the scale, for example, neighborhood poverty rates are less than 10 percent and unemployment rates are roughly 5 percent. At the higher end of the scale, poverty rates top 50 percent and unemployment rates are upward of 25 percent.

a. The original PSID sample includes relatively few Hispanic households. In the late 1990s, the Hispanic sample increased with the introduction of immigrant families into the PSID.

b. People born in 1984 are 25 years old in 2009, and people born in 1979 are 30 years old in 2009.

c. The Transition to Adulthood supplement was administered in 2005, 2007, and 2009 for children who were 12 or younger in 1997 and at least 18 at the time of interview.

d. Census tract is available in the restricted-use PSID starting in 1975. Each PSID year from 1975 forward is assigned a census data year: 1975–84 PSID to the 1980 Decennial Census, 1985–94 PSID to the 1990 Decennial Census, 1995–2004 PSID to the 2000 Decennial Census, and 2005–09 PSID to the 2005–09 American Community Survey (five-year averages). Because census tract is not available before 1975, neighborhood characteristics are not observed for the complete childhood of children born between 1968 and 1974. For children born in these earliest years, data are used in the years available.

e. One weakness of the PSID is that family income and family size, key components of poverty, are measured at different points in time. Family structure is measured at the time of the interview, but income is reported for the prior year. If individuals enter or leave a family from one year to the next, there is a mismatch between family income and the poverty threshold.

f. Our poverty measure uses the poverty thresholds described in Grieger, Danziger, and Schoeni (2008).

g. Because the PSID went to biennial interviewing in 1997, complete childhood poverty histories are not observed for children born in 1980 or later. In these cases, the percentage of years poor is calculated based on the number of years children are observed. Children born in 1980 and 1981 are observed for 17 years (versus 18 years), children born in 1982 and 1983 are observed for 16 years, children born in 1984 and 1985 are observed for 15 years, children born in 1986 and 1987 are observed for 14 years, and children born in 1988 and 1989 are observed for 13 years.

h. The PSID groups residential moves based on reason for move. Reasons that include contraction of housing (e.g., less rent), to save money, and to respond to outside events (e.g., eviction, divorce) are categorized as negative moves.

i. Each neighborhood characteristic is averaged from birth through age 17.