Abstract

Release from incarceration poses significant risk for opioid-associated overdose. Treatment engagement with medications for opioid use disorder prior to community release is an effective overdose mitigation strategy. But this evidence-based intervention is infrequently implemented in rural jails, a gap that can be addressed with the use of telemedicine. The aim of this study was to evaluate a novel telemedicine buprenorphine (tele-buprenorphine) treatment program for incarcerated people diagnosed with moderate-to-severe opioid use disorder (OUD). We conducted a retrospective chart review of data collected from discharged patients who were enrolled in a rural jail-based telemedicine buprenorphine treatment between 4/26/2021–12/17/2022. Outcome measures included community buprenorphine treatment engagement at two weeks following release from jail (primary) and fatal and/or non-fatal overdose events occurring within two weeks of release from jail (secondary). A total of 151 incarcerated patients were enrolled in the tele-buprenorphine program, 98.7 % (n = 149) of whom remained in buprenorphine treatment throughout custody. Of these 149 patients, six were provided with extended-release buprenorphine prior to release, and 23 were transferred to another jail. Of the 120 patients who were discharged into the community, 78 % (n = 93) were engaged in buprenorphine treatment within the two weeks following release. Significantly more people in this group (75 %) received bridge buprenorphine prescription prior to release. These first-of-its-kind data suggest that like in-person jail-based buprenorphine provision, tele-buprenorphine may increase community treatment engagement and possibly prevent opioid overdose and fatality. This report provides proof-of-concept justification for a unique clinical implementation model that warrants wider adoption and evaluation.

For the past decade or more, the US has remained mired in an opioid crisis (Products, 2025). Recently released incarcerated individuals are particularly vulnerable, with as much as 12.7 times greater risk than the general public of overdose death in the weeks following community re-entry (Borschmann, 2024a). Provision of evidence-based medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including buprenorphine, to incarcerated individuals has been tied to decreased post-release overdose deaths (Green et al., 2018) and to increased community treatment engagement (Gordon et al., 2008, Moore et al., 2019, Friedmann et al., 2025). Jails offer a controlled, monitored setting, conducive to initiating buprenorphine treatment, but jails frequently lack buprenorphine dosing expertise and staffing resources, and are challenged with space restraints representing a crucial opportunity to implement creative solutions to expand treatment access (Flanagan Balawajder et al., 2024).

Telemedicine provides a viable and scalable solution for health care and treatment gaps (Rubin, 2019). Calls for widespread adoption of telemedicine for confined populations abound, (Rubin, 2019, Donelan et al., 2020) but reports of telemedicine for addiction treatment with medications in carceral settings is limited. MOUD access is a particularly acute problem in rural communities, which often have existing issues of resource and healthcare shortages (Lister et al., 2020, Morenz et al., 2025)—thus compounding the already challenging issue of access in carceral settings. Our team has provided remote telemedicine buprenorphine (tele-buprenorphine) treatment to a variety of rural clinical settings, (Weintraub et al., 2018, Weintraub et al., 2021a) which we expanded to incarcerated populations in 2020 (Belcher et al., 2021, Spaderna et al., 2025). Currently, we are the primary buprenorphine treatment provider for rural county jail and detention centers in seven jurisdictions—roughly 40 % of all of Maryland’s rural counties. To our knowledge, no study has evaluated the outcomes of jail-based telemedicine treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD). The aim of the current observational study was to evaluate patient outcomes of the first two years of tele-buprenorphine program implementation at one of our rural detention center sites.

1.1. Literature review

1.1.1. OUD is overrepresented and undertreated in carceral settings

People who are incarcerated have been disproportionately affected by the opioid crisis. Estimates suggest that up to 36 % of people with OUD cycle through the correctional system each year, (Boutwell et al., 2007) and that more broadly, 15 % of people who are incarcerated have an OUD (Lenz et al., 2025). Tragically, these individuals also face a significantly higher risk of drug-related overdose death, and several reports have documented fatal opioid overdose as the leading cause of death following release from jail or prison (Alex et al., 2017, Binswanger et al., 2007, Binswanger, 2013, Merrall et al., 2010, Borschmann, 2024b). Local data support these findings; a Maryland state-commissioned report found that the risk of overdose was 8.8 and 8.2 times greater in the first week after release from Maryland prisons and jail, respectively, compared to the period of 90–365 days following release (Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2014). The reasons for this heightened risk are many, but chiefly, without MOUD protocols in place, jails and prisons use withdrawal/detoxification procedures that lower a person's tolerance, leading to a higher risk of overdose upon release (The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder, 2020, Rich et al., 2015).

Decades of research have shown that MOUD—including methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone—are the most effective, evidence-based treatments for OUD (Mattick et al., 2003, Mattick et al., 2014, National Academies of Sciences, 2019). The benefits of MOUD, including decreased overdose mortality, arguably have a higher impact in OUD-enriched carceral contexts. A growing body of literature demonstrates that MOUD provision during and after incarceration reduces opioid use, fatal and non-fatal overdose, and recidivism (Green et al., 2018, Gordon et al., 2008, Friedmann et al., 2025, National Academies of Sciences, 2019, Macmadu et al., 2020, Evans et al., 2022, Lim et al., 2022). MOUD jail programs vary in their design, but the two major models include in-house treatment (usually through the jail’s contracted medical provider, but jails can become federally certified as opioid treatment programs [OTPs]), and partnership with a community OTP for off-site delivery—in either case, treatment is provided with an in-person encounter with a prescriber. Jail-based treatment represents a critical opportunity to initiate OUD treatment and may serve as a significant inflection point in an individual's recovery pathway, even if treatment was not sought prior to incarceration (Spaderna et al., 2025).

Major medical and justice authorities across a wide range of sectors have unilaterally endorsed MOUD provision for incarcerated individuals, including the American Psychiatric Association, (How to Help Those with Opioid Use Disorder in Jails and Prisons, 2025) the American Society of Addiction Medicine, (The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder, 2020) the National Institute of Justice, (Five Things About Substance Use Interventions, 2025) and the National Commission on Correctional Healthcare, (Jail-Based MAT, 2025) among others. Unfortunately, however, MOUD is infrequently offered to justice-involved individuals as standard-of-care. A 2014 analysis of SAMHSA’s Treatment Episodes Data Set-Admission (TEDS-A) data surveyed 72,084 treatment episodes and found that only 4.6 % of justice-referred people received agonist treatment, compared to 40.9 % of clients who were referred through other channels (self- or health provider-referred). Krawczyk et al., (2017) More recently, a nationally representative survey study of local jails across the US found that less than half (43.8 %) offered MOUD to at least some individuals, and only 12.8 % offered them to anyone with an OUD who requested treatment (Flanagan Balawajder et al., 2024). Growing awareness of the paucity of treatment availability for people entering and leaving carceral settings has been met with several responses, including litigation pressuring carceral systems to provide MOUD in line with ethical healthcare standards, (Office of Public Affairs et al., 2025a) increased federal funding to support research on MOUD in carceral settings, (Justice et al., 2025) and an uptick in the number of states (as of November 2023, 16 states) that require that MOUD be implemented in all, or nearly all, state or local correctional settings (admlappa, 2023). Collectively, these events suggest a wave of change with increasing openness to MOUD delivery in correctional settings. But gaps in MOUD healthcare delivery, particularly in rural, geographically constrained areas of the country, stymy this positive momentum (Bunting et al., 2018).

1.1.2. The opioid crisis in rural America

Rural regions have been disproportionately affected by the opioid public health crisis, exhibiting the highest rates of opioid prescribing and the highest per capita opioid-related deaths (Lister et al., 2020, Hedegaard et al., 2020). Driven primarily by shortages of available treatment options, (Haffajee et al., 2019) patients residing in rural areas experience longer wait times and longer driving distances, as well as increased stigma—factors that further challenge OUD treatment (Bunting et al., 2018, Hedegaard et al., 2020, Lofaro et al., 2025, Abraham et al., 2018, Kiang et al., 2021).

Sociocultural factors also contribute to the treatment disparities between rural and urban communities, as well as the higher burden of opioid use in rural populations. Many factors are linked to the prevalence of labor-intensive occupations, which increase the risk of occupational injuries and promote a cultural acceptance of opioid use for pain management (Keyes et al., 2014, Rigg et al., 2018). Additionally, rural populations are typically older, leading to a higher frequency of chronic pain and, consequently, a greater rate of opioid prescriptions (Keyes et al., 2014). Other contributing factors include limited economic opportunities and tightly knit social and family networks that can facilitate the distribution of opioids (Keyes et al., 2014, Rigg and Monnat, 2015). There is a critical need to bridge the OUD treatment gap in rural areas of the United States, for which telemedicine offers a promising solution (Rubin, 2019).

1.1.3. The evolution of telemedicine in opioid use disorder treatment

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) defines telemedicine, or more broadly, telehealth, as two-way, real-time interactive communication between patients and practitioners at a distant site for the purpose of improving patient health (CMS, 2025). Telemedicine platforms have been used for at least several decades to deliver a wide range of psychiatric care, including evaluations, therapy, patient education, and medication management (Services B on HC, 2012). These platforms have been evaluated using various implementation and effectiveness metrics, including feasibility, validity, reliability, patient satisfaction, cost-effectiveness, and clinical outcomes. Previous research has shown that telemedicine is effective in treating various mental health disorders including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder; (Turvey and Fortney, 2017, Hall et al., 2022, Hand, 2022, Shaker et al., 2023) advances that have paved the way for its expansion into OUD treatment.

In the United States, methadone for OUD is a federally regulated treatment exclusively available through certified OTPs. Buprenorphine, however, is a partial μ-opioid receptor agonist approved in 2002, and is an alternative with less regulatory oversight that can be prescribed in office-based settings (Welsh and Valadez-Meltzer, 2005). The use of telemedicine for OUD has increased not only from the demand for solutions to the public health crisis, but as a crucial response following the outbreak of COVID-19 (Yang et al., 2018). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a major barrier to the widespread use of buprenorphine via telemedicine was the 2008 Ryan Haight Act, which effectively prohibited the prescription of controlled substances without a prior in-person patient encounter. This restriction was lifted to allow for safe, social-distanced treatment of OUD, a flexibility that the federal government has extended three times to December 2025 (DEA and HHS Extend Telemedicine Flexibilities through, 2025). We have demonstrated that telemedicine-based OUD treatment yields clinical outcomes—specifically, patient retention and reduction in illicit substance use—that are comparable to those of in-person care (Weintraub et al., 2018, Weintraub et al., 2021a, Weintraub et al., 2021b).

1.1.4. University of Maryland's DART telemedicine for OUD program

The Division of Addiction Research and Treatment (DART) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine has been a leader in providing MOUD (buprenorphine and naltrexone) via telemedicine to rural areas of Maryland's Eastern Shore and western Appalachian communities. Since August 2015, DART has partnered with intensive outpatient programs and behavioral treatment programs in rural counties—including Caroline, Talbot, and Dorchester Counties on the Eastern Shore, and Garrett and Washington Counties in western Maryland—to provide telemedicine-based MOUD for OUD-diagnosed patients. These counties have been disproportionately affected by the opioid epidemic, with opioid overdose death trends showing little sign of reversal. For example, while the state of Maryland saw a decrease in opioid overdose deaths between 2018 and 2019, these specific counties experienced either an increase or a plateau in fatalities (State of State of State of Maryland Opioid Operational Command Center et al., 2025b).

Anecdotally, our clinicians have treated patients in these various rural settings, only to lose them to the revolving cycle of incarceration. In 2019, the state of Maryland passed House Bill (HB) 116 mandating that all local correctional facilities make at least one formulation of each FDA–approved full opioid agonist, partial opioid agonist, and long–acting opioid antagonist used for the treatment of opioid use disorders available to any incarcerated individual in need (Maryland Correctional Services Code Ann. §9–603 [2020]). In response to this mandate, our team applied for and was awarded private foundation funding to launch a new clinical program of treatment with medications via telemedicine to three rural county detention centers across the state (FORE Foundation, 2022). We have reported successful implementation of telemedicine MOUD in rural detention center sites, with treatment engagement and initiation occurring prior to the high-risk period of discharge (Belcher et al., 2021, Spaderna et al., 2025). This program has grown quickly, and we currently provide tele-buprenorphine treatment to 7 different jail and detention center sites across Maryland. The opportunity to expand our clinical work to rural detention center settings has also allowed our team to conduct research in these settings.

The following is the first reported evaluation of a jail-based telemedicine program developed to expand buprenorphine prescribing in this vulnerable population. Data are reported from first encounters of all incarcerated patients who were treated and released in the first 24 months following program implementation at a high-volume detention center site in rural Appalachia.

2. Methods

We report on retrospectively collected data following jail discharge of initial and follow-up treatment episodes of incarcerated patients who were enrolled in our tele-buprenorphine program. Data are stored in REDCap, a HIPAA-compliant database maintained at the University of Maryland (UM) School of Medicine. All data were collected as part of a study protocol approved by the UM Human Research Protection Office (IRB protocol No. HP- 00100535). This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

2.1. Setting

The detention center site is a 234-person rated facility with an average daily census of 185 individuals. Prior to the detention center’s engagement with the telemedicine-based buprenorphine program, methadone and buprenorphine continuation were provided through an MOU with a local opioid treatment program, but no buprenorphine initiation/induction protocol was in place. Program implementation was initiated in February 2021, and the first patient was enrolled in treatment on April 26, 2021. We have reported screening and treatment methods previously, (Belcher et al., 2021) but briefly, the SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral to Treatment) model is used upon entry to the facility by the detention center’s nurse to screen for potential opioid use disorder. Individuals who screen positive are scheduled for an evaluation via secure videoconferencing with a UM provider who obtains a full patient history and performs a thorough clinical exam. For those deemed appropriate for buprenorphine treatment, a patient-centered dosing protocol is ordered. Buprenorphine mono-product is administered as either 2 or 8 mg tablets on a once daily basis by the jail’s nursing staff with correctional officer oversight using diversion mitigation protocols (Belcher et al., 2021). Upon custody release, patients are provided with up to two weeks’ worth of bridge prescription of buprenorphine in the community. Patients with an existing home supply of buprenorphine or immediate access to a community treatment provider are not provided bridge prescriptions. All interactive video conferencing sessions are conducted point-to-point using Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) algorithm via Internet Protocol (IP) connections. The EPIC (Epic Systems Corp) electronic health record (EHR) system is used to enter patient encounter notes, lab results, and to schedule appointments.

2.2. Data collected

This retrospective chart review analyzed data from patients discharged from a jail-based telemedicine buprenorphine program between April 26, 2021, and December 17, 2022. Data were collected from jail intake and discharge records, the electronic health record (EHR), and the Maryland Department of Health Vital Statistics Administration (VSA).

2.2.1. Sources of data

2.2.1.1. Jail records

Upon enrollment, patients signed a release of information to allow the University of Maryland treatment team to access their jail records. Jail intake data included age, self-identified gender (male, female, other), race (Caucasian/White, African American/Black, Native American/Alaska Native, Asian/Asian American, Unsure, Other), ethnicity (Hispanic/LatinX), total years of opioid use, most recent route of administration (intranasal, intravenous, smoked, or oral), comorbid mental health conditions (Depression, Anxiety, PTSD, ADHD/ADD, Bipolar Disorder, Other), and crime charge (property, substance use, violence, or other).

2.2.1.2. Discharge data

Discharge data included discharge date, tele-buprenorphine retention (discharge from tele-buprenorphine program and reason for discharge), whether an appointment was made by the jail re-entry coordinator for the person to continue care in the community, and post-release status (transferred to community inpatient program, transferred to another detention facility, extended-release buprenorphine provided upon release, other).

2.2.1.3. Electronic health record data

EHR abstraction included whether any pre-incarceration MOUD treatment was provided in the week prior to incarceration, buprenorphine dosage (in mg), duration of tele-buprenorphine treatment, whether a buprenorphine bridge prescription was provided at discharge, whether the patient picked up their community buprenorphine prescription, and encounter notes completed by the providing physicians. These encounter notes also provided post-release outcome data, which included community buprenorphine prescription pick-up events, and any noted fatal or non-fatal drug overdose events, based on our physicians’ standard practice of querying prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) information to assess engagement in care following discharge.

2.2.1.4. Vital statistics data

Fatal overdose data were verified through a Data Use Agreement with the Maryland Department of Health Vital Statistics Administration (VSA), which provided data on verified occurrences of deaths among patients discharged in 2021 and 2022. This verification was completed on October 16, 2024.

2.3. Outcome measures

The main outcome measure was community buprenorphine treatment engagement at two weeks post-release from jail. Community buprenorphine treatment engagement was defined as PDMP-confirmed patient fulfillment of a buprenorphine prescription within the 14-day period following release, constituted by a pick-up of either the bridge or any buprenorphine prescriptions provided post-release by a community provider, and was coded as a binomial variable. Secondary outcomes included PDMP-documented fatal or non-fatal overdose events occurring within the 14 days following release from jail. Fatal overdose was verified with VSA data.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software v29 (IBM) and were performed from January 30, 2024, to May 30, 2025. Baseline demographic, clinical characteristics and fatal/non-fatal overdose outcome data are reported as frequencies and percentages, and central tendencies (mean or median) with dispersion (S.D. or range) were used to report continuous data. Pearson χ2 tests were used to compare differences between groups of patients who either had or had not received a bridge buprenorphine prescription on the primary outcome of treatment engagement. A binary logistic regression was used to explore the relationships between various pre-treatment and treatment related covariates on community treatment entry. p < .05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient population characteristics

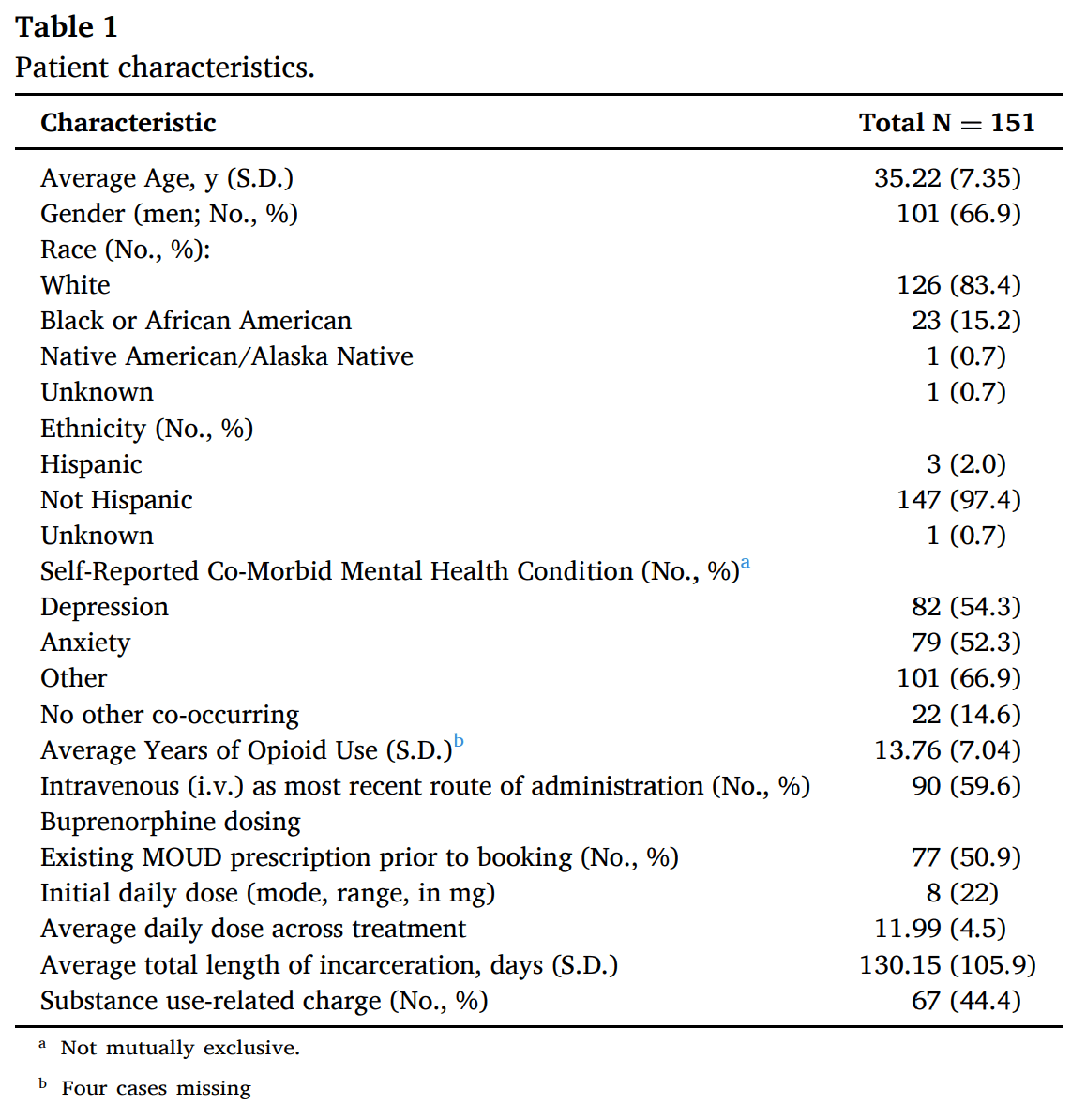

Between April 26, 2021, and December 17, 2022, a total of 151 incarcerated patients with diagnosed moderate-to-severe OUD were enrolled in the telemedicine buprenorphine program. The mean age of the patients was 35.22 (S.D.= 7.35) years, 66.9 % were men, 83.4 % identified as White, and 97.4 % were of non-Hispanic ethnicity. Patients reported an average of 13.76 (S.D. = 7.04) years of opioid use, and 59.6 % of the patients reported intravenous administration for their most recent opioid use. The median prescribed induction dose of buprenorphine was 8 (range=2–24) mg, and patients were maintained on an average of 12 (range=3–24) mg across the duration of treatment. Seventy-six (53 %) of the patients were on buprenorphine treatment prior to jail intake and waited a median one day (IQR=7) to be admitted to the tele-buprenorphine treatment program. Full patient baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

3.2. Primary outcome: treatment engagement

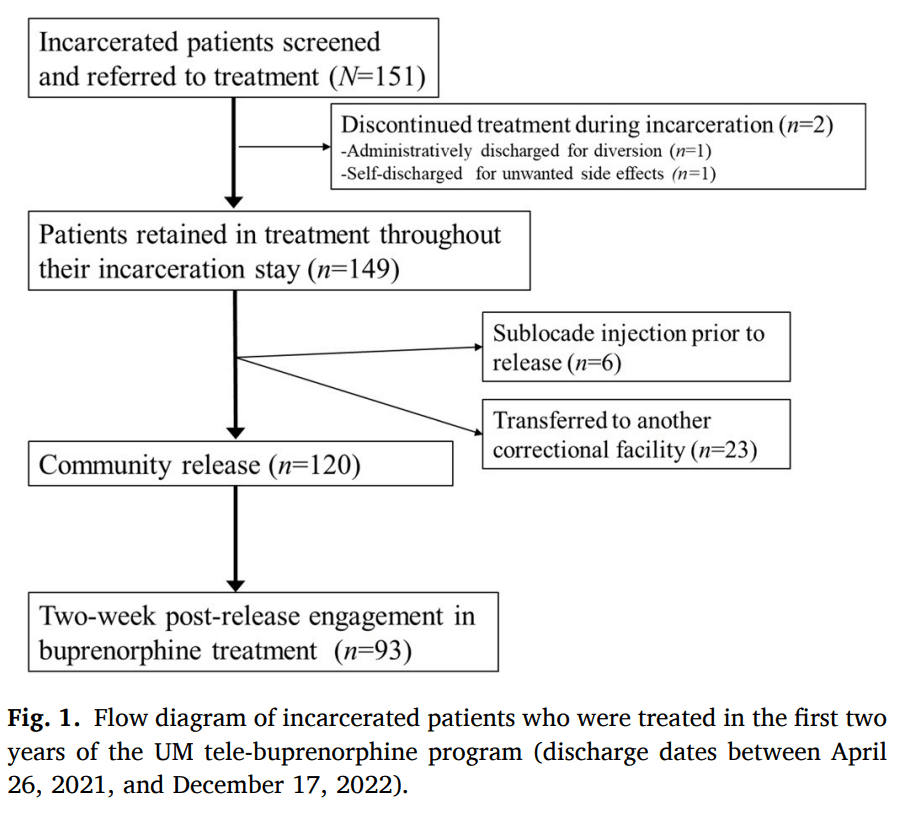

Of the 151 patients, 98.7 % (n = 149) remained in treatment throughout the duration of their incarceration; of the two patients not retained, one individual was discharged for medication noncompliance (diversion) and a second individual discontinued medication due to side effects. Among the remaining 149 patients, six chose to receive extended-release buprenorphine injection prior to their release and 23 patients were transferred to another correctional facility (post-release data from other detention centers or jails was unavailable). These 31 cases were not considered in any further analyses (Fig. 1).

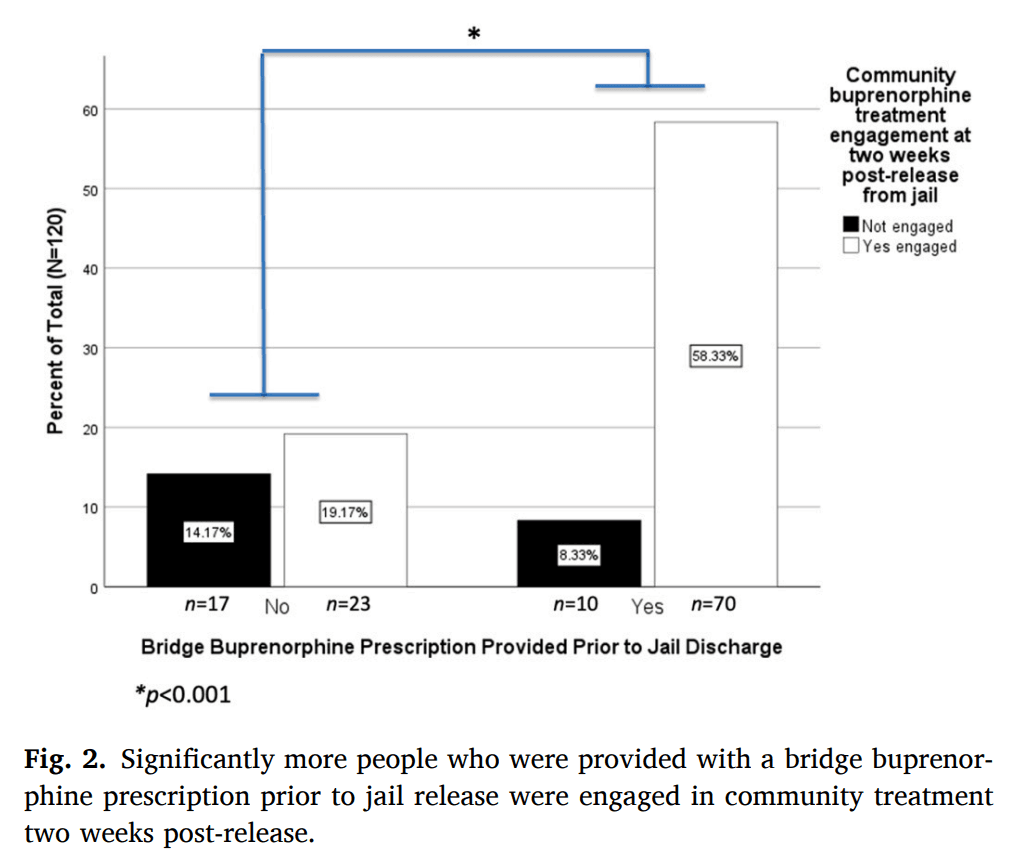

Among the 120 patients who were in buprenorphine care at the time they were discharged from the facility, 93 patients (78 %) were engaged in community-based buprenorphine treatment in the two weeks following their release from the detention center. Seventy of these 93 individuals had been provided with a bridge buprenorphine prescription by our tele-buprenorphine treatment team (Fig. 2). Comparisons revealed a significantly greater proportion of patients who were provided with bridge buprenorphine prescriptions had established community-based buprenorphine treatment, relative to individuals who had not received bridge buprenorphine prescriptions (χ2(1120) = 13.76, p < 0.001; see Fig. 2).

Sixty-one of the 120 individuals considered in final analyses had an existing buprenorphine prescription in the days prior to incarceration and continued their treatment with the jail-based tele-buprenorphine program. Buprenorphine continuation had no impact on the primary outcome, however, as there was no difference in post-release treatment engagement between this group and the group of individuals (n = 59) who were newly inducted in jail (χ2(1120) = 0.173, p > 0.05).

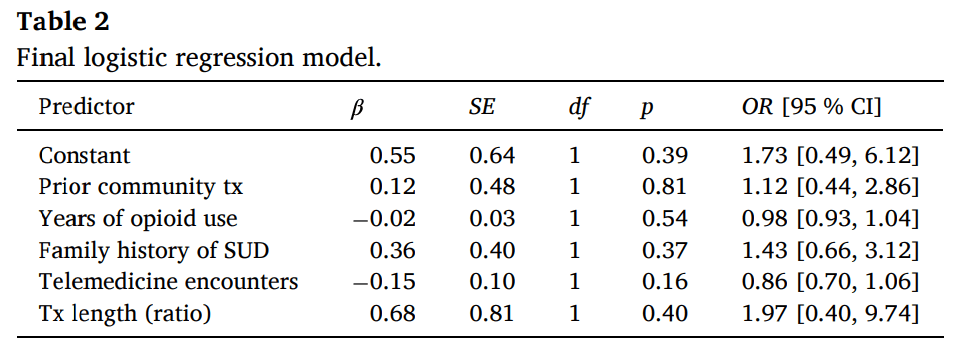

To explore possible relationships between demographics, years of opioid use, family history of substance use, treatment length and the primary outcome of post-release treatment engagement, we performed a binary logistic regression using a step-wise approach. The dependent variable was engagement in treatment within two weeks of release (Yes=1; No=0). Independent variables were entered into the model in two blocks. The first block consisted of generic demographic variables including: (1) age, (2) sex, (3) race, and (4) ethnicity. Participant age was treated as a continuous variable while sex (male=0; female=1), race (White=1; other race=0), and ethnicity (Hispanic=1; Non-Hispanic=0) were treated as dichotomous categorical variables. Race categories were collapsed because only 24 individuals identified as Non-White (23 Black/African American and one Native American). The second block consisted of variables of interest and included: (1) prior community treatment engagement (defined as having a buprenorphine or methadone prescription at the time of incarceration; Yes=1; No=0); lifetime years of opioid use (continuous); self-reported family history of substance use disorders (Yes=1; No=0); total number of telemedicine encounters with UMD providers (continuous); and treatment length (defined as the number of days receiving telemedicine divided by length of stay to control for variable periods of incarceration; continuous). Variables in the first block were entered using a backward elimination method where all variables are entered into the model and at each step, the least significant variable is removed until all the remaining variables have a statistically significant contribution. Variables in the second block were entered simultaneously and preserved in the final model regardless of statistical significance. The results of the model revealed that none of the generic demographic factors in the first block provided a statistically significant contribution to the model; these variables were not included in the final model. Results of the final model are presented in Table 2. In summary, there were no statistically significant predictors of post-release treatment engagement amongst the variables of interest.

3.3. Secondary and exploratory outcome measures

No individuals had a fatal or non-fatal drug overdose event noted in the PDMP within the two weeks following release from jail. VSA data confirmed that no patients died in 2021 or 2022.

4. Discussion

Although several reports have provided incontrovertible evidence for the risk of not providing incarcerated patients with life-saving treatment with MOUD, (Borschmann, 2024a, Green et al., 2018, Binswanger, 2013) current treatment models still rely largely on jail-based providers with local expertise with buprenorphine dosing or community providers to initiate treatment following discharge from carceral settings. With the dual benefit of reducing the high risk of post-release overdose death and increasing MOUD community treatment engagement, (Degenhardt et al., 2014) MOUD induction during incarceration (and prior to the vulnerable period of release from jail) should be standard of care. Yet jail-based MOUD treatment initiation is rare, reportedly as little as 13 % (Sufrin et al., 2023). There is a dire need for increased access to equitable treatment, particularly in rural areas of the U.S (Rubin, 2019). Our data provide initial evidence that telemedicine can be leveraged to meet this gap. These data add to the limited but growing evidence supporting telemedicine as a method to connect incarcerated patients to MOUD treatment Duncan et al. (2021) and expand it to demonstrate that jail-based buprenorphine initiation was associated with a high rate of patients initiating buprenorphine in the community. Specifically, nearly all (~99 %) of the patients were retained in treatment during their incarceration, with a high rate of community buprenorphine engagement (78 %). Despite consistent reports of younger age as a risk factor for MOUD treatment retention, (Brorson et al., 2013, Krawczyk et al., 2021) we found no patient characteristics (demographics, pre-treatment and treatment-related variables) that significantly predicted post-release engagement; however, a younger population and the fact that factors surrounding people’s release from jail (inherently tied to treatment duration) may explain this departure from published findings. These data further suggest that provision of pre-release bridge buprenorphine yields increased treatment engagement post-release. Finally, although this study is limited in its scope and observational nature, the fact that there were no documented fatal or non-fatal overdoses is an encouraging signal to suggest that telemedicine-based treatment in jail may be an effective intervention for decreasing opioid-associated death. Collectively, these data underscore the utility of telemedicine to fill the urgent need for strategies to increase access to evidence-based treatment for incarcerated populations.

5. Limitations

This study is limited in its retrospective design and lack of a well-controlled comparator arm. In a real-world implementation setting, a comparative effectiveness trial would provide the clearest information regarding effectiveness. Additionally, as an observational trial, we were unable to collect self-report data for the reasons why individuals did not engage in community buprenorphine treatment, nor were we able to verify buprenorphine adherence through urine drug screening. Moreover, provider encounters are documented at only one time point following release from the jail treatment program; thus, we were unable to collect data on longer-term follow-up of buprenorphine prescriptions. Furthermore, although we were able to verify fatal overdose incidences through VSA, there might have been underreporting of non-fatal overdoses into the PDMP. Finally, as a single-site observational trial, these data are not generalizable to other detention centers or jails.

6. Conclusions

There is an urgent need for evidence-based treatment with MOUD in carceral settings. Our data provide preliminary data that telemedicine provides a low-threshold, effective approach to treating incarcerated individuals, particularly in rural areas of the US, and warrants prospective evaluation using randomized controlled studies.