Abstract

The present study surveyed judges to examine how they consider and apply scientific information during sentencing determinations. Judges in criminal courts are increasingly asked to assess and make decisions based on evidence surrounding psychiatric disorders, with unclear results on sentencing outcomes. We qualitatively interviewed 34 judges who have presided over criminal cases in 16 different states and also administered vignette surveys during the interviews. We asked them to make sentencing decisions for hypothetical defendants in cases presenting evidence of either no psychiatric disorder, an organic brain disorder, or past trauma, as well as to rate the importance of different goals of sentencing for each case. Results indicated that the case presenting no evidence of a mental health condition received significantly more severe sentences as compared to either psychiatric condition. Judges' ratings of sentencing goals showed that the importance of retribution was a significant mediator of this relationship. Trauma was not deemed to be as mitigating as an organic brain disorder. These results provide unique insights into how judges assess cases and consider sentencing outcomes when presented with scientific information to explicate defendants' behavior. We propose ways forward that may help better integrate scientific understandings of behavior into criminal justice decision-making.

1. Introduction

Over the last several decades, research in the biological and behavioral sciences has begun to build a better understanding of factors and characteristics that can increase one's likelihood of antisocial and criminal behavior (Ling et al., 2019; Raine et al., 1997; Walt & Jason, 2017). Mental health conditions can impact many facets of human decision-making and actions relevant to social functioning, including negative emotionality, impulse control, and empathy (Candini et al., 2020; Jansen et al., 2020; Whiting et al., 2021). Studies have supported that criminal offending can be associated with factors including mental illness, genetics, and an array of life experiences (Brunner et al., 1993; Ferguson, 2010; Kerridge et al., 2020). As such, these and other findings from the bio-behavioral sciences have been considered highly consequential for the criminal justice system and how decisions are made within the criminal-legal process (Barnes et al., 2015; Glenn & Raine, 2014). If such information is misunderstood or misapplied, it may lead to detrimental outcomes for individuals experiencing mental health conditions.

As a result of growing evidence on the impact of mental health on behavior, science has become a more common feature in criminal courts; judges are increasingly asked to make decisions based on their understanding of bio-behavioral scientific evidence (Greene & Cohen, 2004; Khalid et al., 2024; Thomaidou & Berryessa, 2023; Walt & Jason, 2017). The effects of scientific evidence have been thought to be potentially most impactful in sentencing determinations, as it can potentially speak to the degree of a defendant's behavioral control and responsibility (Aspinwall et al., 2012; Goodman-Delahunty & Sporer, 2009; Kim et al., 2015). Indeed, neurobiological findings may influence decision-makers and whether they believe certain behaviors may be seriously or sometimes irrepressibly shaped by a range of innate and environmental factors (Batastini et al., 2018; Mulvey & Iselin, 2008; Wayland, 2007).

There are no steadfast rules or guidelines that define if and how mental disorders should impact sentencing. Mental health conditions are considered in the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, but the “unusual degree” requirement (USSC §5H1.3, p. 461, 2021) limits the impact of psychological and psychiatric evidence to be rendered as mitigating only in the most severe cases. Research suggests that, in practice, evidence of mental health disorders can function as either mitigating or aggravating–or neither–generally yielding inconsistent effects on sentencing at both the federal and state levels (Aspinwall et al., 2012; Cheung & Heine, 2015; Denno, 2015; Guillen Gonzalez et al., 2019; Scurich & Appelbaum, 2015).

As legal actors often have little expertise in mental health and bio-behavioral sciences more generally, their assessments of the nature, severity, persuasiveness, or relevance of mental health conditions are likely critical in sentencing determinations. Existing research has identified that one common distinction that may bear on and result in differential sentencing determinations is whether a mental disorder is perceived to be innate or acquired (Appelbaum & Scurich, 2014; Barnett et al., 2007; Berryessa, 2018a; Davidson & Rosky, 2015). As opposed to evidence of trauma-related disorders or other conditions acquired through life experiences, evidence of disorders that are organic, genetically, or innately based is sometimes considered more tangible, reliable, and as potentially having more mitigating effects on sentencing (Allen et al., 2019; Berryessa, 2018b; Khalid et al., 2024). For example, neuroimaging evidence and evidence of a brain lesion have been shown to consistently carry more weight as mitigating factors compared to psychological evidence, including that about prior life experiences (Gurley & Marcus, 2008).

On the other hand, the effect of traumatic experiences and other acquired psychological problems on sentencing appears to be more arbitrary. Judges have been found to be skeptical and uncertain regarding the clinical diagnosis of trauma, potential malingering, and the causality between trauma and criminal behavior (Khalid et al., 2024). A recent study showed that a history of psychological trauma was less successful than organic brain disorders in eliciting mitigation for judges (Khalid et al., 2024). At the same time, reviews of case law show that childhood trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are among the least mitigating mental disorders in a sample of judicial sentencing opinions (Thomaidou & Berryessa, 2023) and are often not considered relevant or convincing (Berger et al., 2012). Studies conducted on mock jurors also show that organic or innate brain disorders have more substantial mitigating effects on sentencing compared to mental health conditions acquired through life experience, such as PTSD (Berryessa, 2018b).

Overall, a large body of evidence suggests that scientific explanations on influences to a defendant's behavior can lead to disparate sentencing decisions (Allen et al., 2019; Denno, 2015; Guillen Gonzalez et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2015; Thomaidou & Berryessa, 2023). The range of objectives considered within criminal punishment may be one of the main reasons for sentencing disparities in U.S. contexts. For example, the U.S. Sentencing Commission acknowledges that sentencing in the U.S. encompasses five philosophical goals that may be applied differently across cases and circumstances–combining rehabilitation, restoration, deterrence, incapacitation, and retribution as the purposes of punishment (Federal Sentencing Guidelines, 2018; Rappaport, 2003). However, the application or consideration of specific sentencing goals is not mandated by the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, and the weighing of their importance is not defined by law at the federal or state levels (Carroll et al., 1987; Ezorsky, 2016; Thomaidou & Berryessa, 2024).

Judges' considerations of the goals they hope to achieve through punishment may be influenced by the type of bio-behavioral evidence presented at trial (Bouhours & Daly, 2007; Guillen Gonzalez et al., 2019). The objectives of retribution and restoration focus on more socio-moral aspects of punishment and may be less applicable when a mental health condition indicates that an individual has diminished control over their behavior (Small, 2020; Xie et al., 2022). Restoring justice for victims and society as a whole has generally been found to be less applicable in light of evidence that a mental health condition influences behavior (Garner & Hafemeister, 2003; Thomaidou & Berryessa, 2022). Further, whether retribution is considered an appropriate punishment objective relates to perceptions of agency and blameworthiness (Berryessa, 2018b; Miethe & Lu, 2005). Indeed, lower attributions of moral responsibility stemming from beliefs that an individual has less control over their actions due to a mental disorder have been shown to reduce punitiveness in prior experimental work (Berryessa, 2018b; Clark et al., 2014; Roberts & Golding, 1991; Shariff et al., 2014). Thus, if and when judges view mental disorders as diminishing individuals' control over their actions, judges could opt for less punitive approaches and prioritize rehabilitation over retribution or restoration (Bouhours & Daly, 2007; Shariff et al., 2014).

Conversely, views of individuals with mental disorders as more dangerous may also influence sentencing outcomes–potentially leading to more punitive sentences aimed at incapacitating defendants to protect society (Batastini et al., 2018; Davidson & Rosky, 2015). This may be especially true for defendants who present evidence of an innate brain disorder that may be considered less amenable to rehabilitation (Berryessa, 2018a; Ezorsky, 2016). Genetic and severe mental disorders that present with significant perceptual and behavioral symptoms are more likely to be viewed as permanent or difficult to overcome, thus exaggerating the risk of future dangerousness (Alimardani et al., 2023; Appelbaum & Scurich, 2014; Berryessa, 2018a). Still, the link between mental disorders and sentencing aggravation seems to be weaker for females as compared to male defendants (Davidson & Rosky, 2015) and depending on the prior knowledge and beliefs of decision-makers (Scurich & Shniderman, 2014).

Although the distinction between innate and acquired disorders may offer some explanatory value, current research has yet to identify a clear rationale for why certain disorders are considered mitigating and others are considered aggravating (Shniderman, 2014). Moreover, our understanding of the mitigating effects of specific disorders largely stems from research conducted on mock jurors and the lay public (Appelbaum et al., 2015; Berryessa, 2018b, Berryessa, 2020; Shariff et al., 2014; Thomaidou & Berryessa, 2022). However, judges presiding over cases involving individuals with and without mental disorders may harbor differing opinions, influenced by their firsthand experiences and professional training.

Overall, evidence-based science on human behavior may be informative for evolving criminal justice policy and justice systems about fair punishment practices (Atiq & Miller, 2018; Connell, 2003; Wayland, 2007). For this to be achieved, however, how scientific explanations for behavior may be considered in decisions made by judges in criminal sentencing need to be more fully understood. In the absence of well-defined sentencing rules or guidelines surrounding mental disorders, it is imperative to systematically examine and quantify factors that judges consider during these sentencing determinations. While qualitative analysis of interview data can be used to draw valuable insights into judges' opinions and decision-making processes more holistically, quantitative approaches may yield more generalizable inferences from small samples of hard-to-reach populations such as judges who preside over criminal cases.

The current study surveyed U.S. state court judges and presented them with scientific evidence in three hypothetical criminal cases. We asked them to make sentencing decisions and rate the importance of the goals of sentencing they hoped to achieve through these determinations in each case. The main objective of this research was to compare their sentencing decisions and ratings of sentencing goals when considering cases involving no mental disorder, an innate disorder (organic behavioral disorder), and an acquired disorder (history of psychological trauma). We hypothesized that judges would be most punitive in their sentencing decisions when no scientific explanation of behavior was given and that this would be attributable to differential emphasis on the five goals of sentencing (specifically retribution and incapacitation).

2. Methods 2.1. Recruitment and sample

Contact details for U.S. state court judges were obtained from the judicial database American Bench. A sample frame of 1000 random judges was taken from this database for potential recruitment. A power analysis was performed using the statsmodels library in Python to determine the adequacy of sample size for conducting post-hoc tests for a within-subjects ANOVA with three levels. The power analysis indicated that a total sample size of 40 observations would yield an estimated power of β ≈ 0.791, which is considered high. Based on this target sample size and an expected response rate of approximately 5%, we contacted 880 judges from this random sample frame for potential participation via email, including an interview invitation, consent sheet, and contact information.

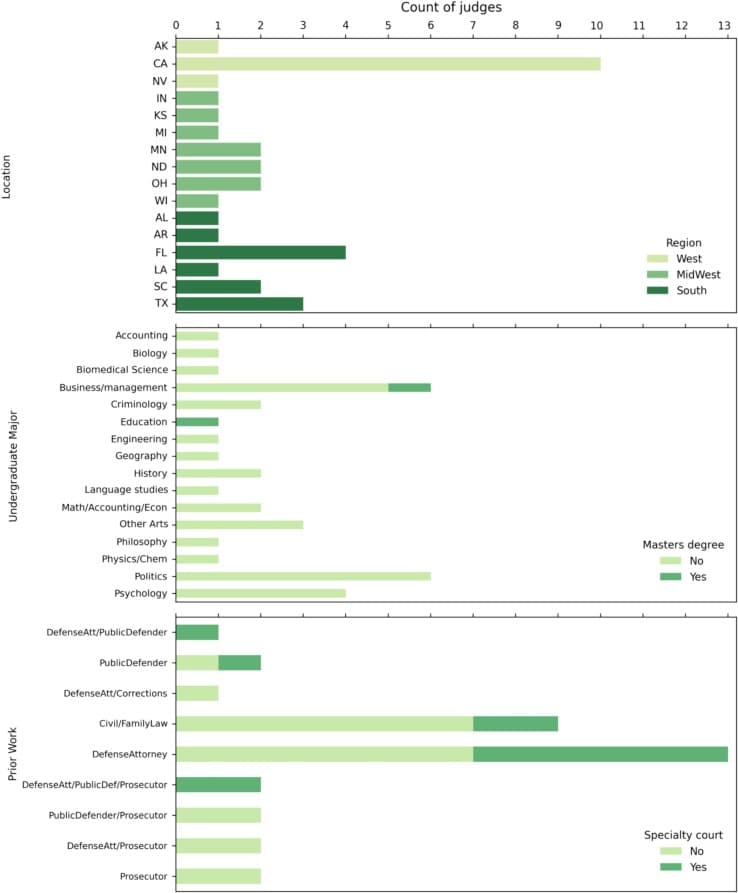

In total, data were obtained from a final sample of 34 state court judges who currently are or have presided over criminal cases in 16 states. Before the interview, all judges provided verbal consent for participation. Fig. 1 displays the different jurisdictions judges were in, the disciplines they majored in during their undergraduate studies, and the nature of their prior work. Approximately 60% of judges worked as defense attorneys or public defendants at some point in their careers before becoming a judge. In comparison, about 24% had worked as prosecutors, and 26% worked in civil or family law, with some overlap between these categories. Most judges in our sample were men (n = 24). Two judges were over 70 years old, 13 were over 60 years old, 10 were between 50 and 59 years old, and 9 were between 40 and 49 years old. The most experienced judge had over 30 years of experience, followed by 20–29 years (n = 5), 10–19 years (n = 1), 5–9 years (n = 9) and fewer than 5 years (n = 8).

Fig. 1. Sample characteristics, including judges' jurisdictions, geographical regions, disciplines they majored in during their undergraduate studies, whether they hold a master's degree, the nature of their prior work, and whether they are involved in a specialty court.

2.2. Interview protocol

The data reported here are part of a dataset obtained through semi-structured interviews lasting approximately 1 h. The present manuscript focuses on the quantitative aspect of the interview, which comprised a survey describing three hypothetical criminal cases involving different scientific explanations for a defendant's behavior, as well as a sentencing goals questionnaire. Judges were asked to select a sentence and rate the importance of sentencing goals for each hypothetical case. The interviewer noted numerical responses in a survey built in Qualtrics XM. The remaining part of the interview protocol during the semi-structured interviews, as well as the data collected during its administration, were not used for the present inquiry and, therefore, will not be detailed here. The authors' Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study.

2.3. Measures

This study employed a within-subjects design, with all participants being exposed to all hypothetical cases. The description of the cases was based on vignettes published previously in related studies (Berryessa, 2017a, Berryessa, 2021). It was kept as short as possible–primarily focusing on the violent nature of the offense and emphasizing the differences between the types of scientific evidence presented. At the beginning of the semi-structured interview, all three hypothetical cases were presented to all judges in a randomized order, to avoid order effects. We analyzed the potential effect of the order in which cases were presented and found no order effects (p < 0.01). To control demand characteristics, we presented the hypothetical cases at the start of the interview, with minimal information given regarding the objectives of the study. The cases were described in the following way:

“Imagine an offender, a 29-year-old man, a first-time offender, that is found guilty of aggravated assault of a delivery driver, after getting into a traffic-related altercation with him. The victim was hospitalized for two weeks and eventually made a full recovery. In this hypothetical jurisdiction, the guidelines for this level of offense allow for discretionary sentencing, without minimums or maximums. I will now ask you about three different types of evidence.

[No disorder] When the defendant's attorney has not made any mention of a medical or psychiatric evaluation, and there is no scientific evidence of any behavioral disorder, which of the following sentences would you select?

[Brain disorder] Imagine that the defendant's attorney has presented as scientific evidence a brain scan, indicating the presence of an organic behavioral disorder, that research shows can increase aggressive or antisocial behavior, which of the following sentences would you select?

[Traumatic disorder] If the offender's attorney has presented as scientific evidence a clinically assessed past traumatic experience, such as abuse during childhood, that research shows can increase aggressive or antisocial behavior, which of the following sentences would you select?”

The sentence options were:

[Treatment] No prison or jail time, but a treatment order or some form of mandatory rehabilitation.

[Probation] No prison or jail time, but supervised probation or community service.

[Prison] imprisonment or jail time.

[Imprisonment length] if [imprisonment is selected], please indicate how many months or years.

These options were phrased broadly as “would you opt for imprisonment or not” followed up with “how long would a prison sentence approximately be” if prison was selected or “would you then opt for something like probation or community service, or would you focus on ordering some type of treatment or rehabilitation program”. Ultimately, judges could select one answer from three possible broad types of sentences as listed above. The sentencing choices were phrased so that they could clarify and maximize the difference between the least punitive option of only ordering a treatment, the option of probation without treatment, and a custodial sanction without treatment. When participants inquired about specifics or indicated that they would opt for a combination of the three sentencing options, they were reminded of the instructions, the hypothetical nature of the cases, and that they should select the principal or most important part of the sentence they would choose to render.

After sentences were selected, judges were asked to rate the importance of each of the five main sentencing goals for each case from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (completely important). Short descriptions of the goals were provided as follows, based on a previous study (Berryessa, 2020):

Rehabilitation: helping the offender to change their behavior and stop committing crimes.

Restoration: achieving justice by allowing reconciliation with the victim or community.

Deterrence: discouraging similar crimes by showing that crimes like this one get punished.

Retribution: making the defendant ‘pay’ for their crime.

Incapacitation: keeping the defendant from committing crimes by removing him from society.

Judges were asked to consider the importance of the goals in terms of the specific sentences they selected for each case.

2.4. Analytical plan

Reported variables related to sample characteristics include demographics and judges' educational and professional experience. The present paper does not focus on inter-individual differences in sentencing; the primary analysis concerned differences in sentencing between the different scientific evidence presented in each fictional criminal case. The type of hypothetical criminal case was the main predictor variable with three levels (No disorder, Brain disorder, Traumatic disorder). The ratings on the importance of each of the goals of sentencing were used as covariates and mediator variables, treated as a continuous scale with five levels from least to most important (1 to 5). The outcome variables were Imprisonment length (number of months) and the type of sentence, treated as an ordered categorical variable with three levels, from least to most severe (Treatment, Probation, Prison).

Summary statistics were first performed. Demographics and the main variables of interest were plotted. No outliers were present in the data (indicated by Mahalanobis distance). The assumptions for (linear) regression were checked on each of the models, and, where applicable, violations were noted, and transformations and/or non-parametric tests were performed. In inferential analyses, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was first performed, with the type of case as the predictor variable and Imprisonment length as the outcome variable. Where results were significant, Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc tests were performed to elucidate specific differences between the three levels of the predictor variable. Next, the ratings of the importance of the five goals of sentencing as rated by judges for each hypothetical case were added as covariates in an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. Pairwise comparisons were again planned to examine the specific effect of each sentencing goal on the outcome variable.

In the next step of the analysis, an ordinal logistic regression was used to examine the types of sentences that judges selected for the hypothetical cases, with ‘No disorder’ as the reference category. Instead of adding covariates to the logistic regression, we planned to conduct mediation analyses to extract more detail regarding the relationships between the type of case, the goals of sentencing, and the severity of sentences selected. Mediation analyses were conducted separately for each of the goals of sentencing, using ordinal logistic regressions (c and b paths) and OLS regressions (a paths).

3. Results

3.1. Summary statistics

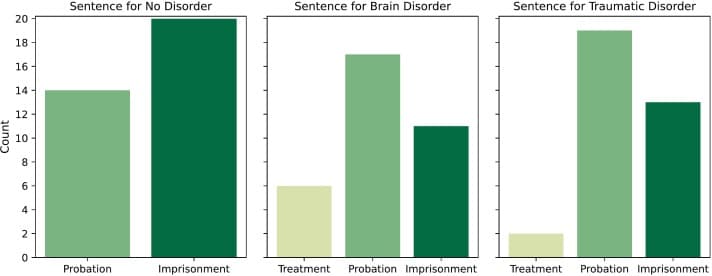

The average Imprisonment length selected by judges was 2.64 months, with No disorder given the longest mean sentence (4.18 months), followed by the Brain disorder (1.91 months) and Traumatic disorder (1.82 months). For the case with No disorder evidence, most judges selected a Prison sentence (n = 20), while for the Brain disorder and Traumatic disorder cases most judges selected Probation (n = 17) (n = 19). Fig. 2 displays the counts for all sentences selected for the hypothetical criminal cases.

Fig. 2. The type of sentence selected by judges for each of the three hypothetical criminal cases.

3.2. Imprisonment length

The ANOVA results revealed a statistically significant effect of the type of case on Imprisonment length (F(2, 99) = 3.537, η2 = 0.067, p = 0.032). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Tukey's HSD showed that the model's overall significance was primarily influenced by the comparison between No disorder and Traumatic disorder. The mean Imprisonment duration for No disorder was 2.4 months higher than that of the Traumatic disorder (p = 0.054) and 2.3 months higher than the Brain disorder (p = 0.066). The Imprisonment length for the Brain disorder case was only 0.1 months higher than the Traumatic disorder (p = 0.9). None of the pairwise comparisons reached significance at p < 0.05.

When adding the goals of sentencing as covariates, the analysis revealed a significant overall effect of the model (F(7, 94) = 2.314, R2 = 0.147, η2 = 0.035, p = 0.032). Pairwise comparisons showed that the goal of Retribution was the only covariate with a significant effect on Imprisonment lengths (b = 0.9068, t = 2.459, p = 0.016), suggesting that as the importance of Retribution increased, sentencing severity also increased. The sentencing goals of Rehabilitation, Restoration, Deterrence, and Incapacitation did not exhibit statistically significant effects on the outcome variable (all p > 0.05).

While the assumptions of independence and homogeneity of variances were met, visual inspection and a Shapiro-Wilk test showed that the data were skewed (towards 0 months imprisonment, given the majority selected Probation and Treatment sentences) and not normally distributed. The data and residuals still did not reach adequately normal distribution after using a log function to transform and standardize the outcome variable. Therefore, a non-parametric alternative, the Kruskal-Wallis test, was employed. The Kruskal-Wallis test yielded significant results, indicating differences in Imprisonment durations among the different types of scientific evidence presented (H = 6.161, p = 0.045). This finding indicated that at least the No disorder case differed significantly from the others in terms of support for Imprisonment length. Non-parametric pairwise comparisons confirmed evidence of a Brain disorder (p = 0.024) and Traumatic disorder (p = 0.042) led to significant differences in Imprisonment durations compared to the case with No disorder. The Brain and Traumatic disorder cases did not differ significantly from each other (p = 0.821).

3.3. Type of sentence

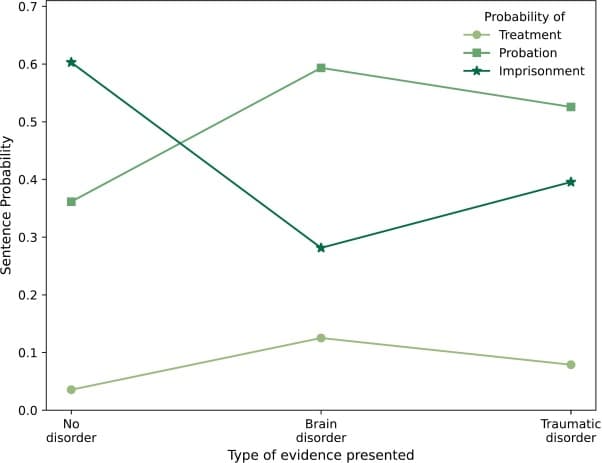

An ordinal logistic regression used to examine the effect of the type of criminal case on the type of sentence selected by judges showed that the odds of selecting a more severe sentence type were significantly lower for the case involving evidence of a Brain disorder compared to No disorder (b = −1.355, SE = 0.498, p = 0.006; Fig. 3). The difference between No disorder and Traumatic disorder cases did not reach significance (b = −0.841, SE = 0.476, p = 0.077). In simple terms, compared to No disorder, the case presenting evidence of a Brain disorder was less likely to receive a severe sentence.

Fig. 3. Results of the logistic regression. The dark green line marking each type of fictional case with a star shows that cases with No disorder evidence had the highest probability of receiving Prison sentences, while the opposite was true for Treatment and Probation. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

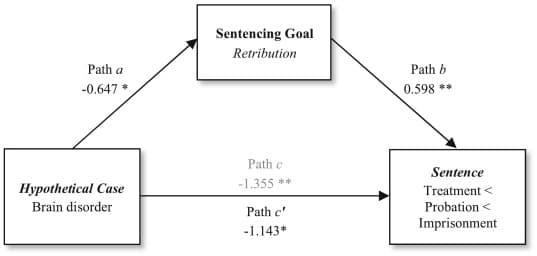

Finally, the results of a mediation analysis (Table 1) showed that ratings on the importance of the sentencing goal of Retribution was a significant mediator of the relationship between the type of case and the type of sentence selected by judges (Fig. 4). For the Brain disorder case, all paths were significant (path a: b = −0.647, SE = 0.286, p = 0.026, 95% CI [−1.215, −0.079]; path b: b = 0.59, SE = 0.186, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.234, 0.962]). The relationship between case and sentence was weakened when controlling for the mediating effect of Retribution (total effect without the mediator in the model, path c: b = −1.355, SE = 0.498, p = 0.006, 95% CI [−2.331, −0.379]); direct effect with mediator, path c’: b = −1.143, SE = 0.517, p = 0.027, 95% CI [−2.156, −0.130]). Detailed mediation results are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. All computed mediation paths.

Coeff. (Std. Error) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Predictor | Path: c total / c’ direct | Path: a | Path: b |

0. Total model: No Mediator | |||

Hypothetical case: | |||

Brain disorder | −1.355** (0.498) | ||

Traumatic disorder | −0.842 (0.476) | ||

1. Mediator: Rehabilitation | |||

Hypothetical case: | |||

Brain disorder | −1.298* (0.513) | 0.206 (0.191) | −0.783** (0.275) |

Traumatic disorder | −0.581 (0.498) | 0.382* (0.191) | |

2. Mediator: Restoration | |||

Hypothetical case: | |||

Brain disorder | −1.452** (0.510) | −0.500 (0.272) | −0.180 (0.179) |

Traumatic disorder | −0.961 (0.494) | −0.618* (0.272) | |

3. Mediator: Deterrence | |||

Hypothetical case | |||

Brain disorder | −1.431** (0.520) | −0.206 (0.293) | 0.578** (0.184) |

Traumatic disorder | −0.834 (0.497) | −0.235 (0.293) | |

4. Mediator: Retribution | |||

Hypothetical case: | |||

Brain disorder | −1.143* (0.517) # | −0.647* (0.286) | 0.598** (0.186) |

Traumatic disorder | −0.575 (0.500) | 0.647* (0.200) | |

5. Mediator: Incapacitation | |||

Hypothetical case: | |||

Brain disorder | −1.556** (0.516) | 0.412 (0.309) | 0.351* (0.165) |

Traumatic disorder | −0.928 (0.488) | 0.118 (0.309) |

Note: The five mediators represent the influence of each of the five goals of sentencing. No disorder was the reference category. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; # Significant mediation.

Fig. 4. Significant partial mediation model with the importance of Retribution explaining the relationship of having a Brain disorder, rather than No disorder (reference category), and receiving a more severe sentence. Path c in grey font is the total effect before adding the mediator to the model. Coefficients and significance levels are displayed. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the potential impact of scientific explanations of behavior on sentencing outcomes for judges. We interviewed U.S. judges who have presided over criminal cases and asked them to make sentencing decisions for hypothetical defendants presenting either no evidence of a mental health condition, evidence of an organic brain disorder, or evidence of an acquired disorder stemming from past traumatic experiences. Overall, the case presenting no evidence of a mental health condition received the most severe sentences, with a statistically significant difference between no disorder and brain disorder, both in terms of the length of imprisonment and type of sentence selected. The goal of retribution had the strongest effects as a covariate and mediator of sentencing decisions. These findings suggest that certain types of mental health evidence may influence sentencing decisions, with judges considering how retributive aspects of punishment may apply to different explanations of behavior.

Scientific evidence suggesting the presence of an organic brain disorder appeared to lead judges to select less punitive sentencing options, as compared to a hypothetical defendant without any disorder or a defendant with a history of psychological trauma. This was reflected both in reduced imprisonment lengths and in a significant increase in selecting treatment as a sentence. This is in line with previous research showing that, for participants acting as mock judges, neurobiological evidence elicited shorter prison sentences and longer terms of involuntary hospitalization as compared to psychological evidence that was not presented as being biologically based (Allen et al., 2019). Mechanistic explanations of particular innate disorders, such as psychopathy, have also previously been shown to mitigate sentencing (Aspinwall et al., 2012) and may suggest that such explanations of behavior can help to reduce punitiveness (Khalid et al., 2024).

Consistent with our findings, previous research using lay participants has found that evidence of innate conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) decreased attributions of personal responsibility, support for retribution, and support for prison sentences (Berryessa, 2018b). In the present study, the mediating role of the sentencing goal of retribution may indicate that, in light of evidence of a brain disorder, the importance of making defendants pay for their crimes may be viewed as less important and lead to reduced punitiveness. Indeed, in general, people may rely more on the retribution rationale to guide their sentencing decisions as compared to other goals of punishment (Carlsmith et al., 2002). When considering biological evidence that may challenge individuals' degree of control over their behavior, reduced support for retribution may be an especially pertinent factor in sentencing decision-making processes for some judges. Still, professional judges may possibly have made their sentencing decisions in the hypothetical cases presented to them based on conventions and the precedent that they are familiar with, rather than moral assessments influenced by mental health evidence. Future studies could further leverage quantitative measures and directly measure how judges view the importance of making defendants with mental disorders pay for their crimes.

It is surprising that the sentencing goal of rehabilitation was not a significant mediator of punitiveness, especially given that previous studies have suggested that bio-behavioral evidence can affect the extent to which defendants are perceived as amenable to treatment (Berryessa & Wohlstetter, 2019; Marshall et al., 2012; van Es et al., 2020). A systematic review of the relevant literature on judicial decision-making based on scientific evidence, for example, indicated that perceived treatability of a mental disorder most often results in lower prison sentences (van Es et al., 2020). One explanation for the lack of consideration of rehabilitation in this study could be that some judges may base their decision-making on the rationale that punishment in itself is a rehabilitation option and as a deterrent against future crimes (Kim et al., 2015). Mulvey and Iselin (2008) point out that in juvenile cases, criminal justice actors judge amenability based on their own intuitions, instead of relying on relevant science. Indeed, a meta-analysis found that psychiatric disorders had negative effects on perceptions of treatment amenability among lay people, but not among criminal justice professionals (Berryessa & Wohlstetter, 2019). Our results may thus reflect judges' tendencies to consider treatment amenability less and to place particular faith in the rehabilitative potential of custodial punishment–potentially drawing these views from their own professional experiences. Evidence of trauma was not viewed to be as mitigating as an organic brain disorder, corroborating earlier research indicating that disorders like PTSD may not inherently lead to reduced support for imprisonment or retribution or enhance support for rehabilitative options (Berryessa, 2018b). In the same study, addiction, another acquired disorder, produced comparable results and demonstrated no mitigating impacts on sentencing (Berryessa, 2018b). Moreover, Kim et al. (2015) found that a defendant with an abusive past received a shorter recommended sentence as compared to that of than a defendant from a loving family when biological information about his adverse life experiences was presented. However, in the absence of biological information, trauma in that study was perceived as increasing the defendant's dangerousness and he received a longer recommended sentence (Kim et al., 2015). Trauma has even been shown in some cases to have aggravating effects on sentencing, even when participants did not perceive the offender as dangerous (Appelbaum & Scurich, 2014).

Such evidence on the lack of mitigating effects of trauma in criminal sentencing is concerning. Baron and Sullivan (2018) describe that emerging behavioral science evidence suggests that individuals with a history of trauma have diminished control over their processing of and reactions towards an array of environmental stimuli, including reactions that could potentially result in criminal behavior (Baron & Sullivan, 2018). Yet, the U.S. public and legal professionals have both expressed concerns that a history of trauma and other risk factors gained through early life experiences could be used to excuse criminal behavior (Berryessa, 2017b; Heath et al., 2003; State v. Mitchell, 2021). In their review of case law and relevant literature, Yacoub and Briggs (2022) argue that there is a need to clarify the role of disorders such as PTSD in criminal codes, so as to enable courts to make more accurate and rational decisions when faced with defendants who may lack criminal culpability due to the impacts of traumatic experiences (Yacoub & Briggs, 2022). Indeed, acquired disorders such as trauma may be erroneously presumed to be easily faked or as having a lesser impact on behavioral control (Berger et al., 2012). Indeed, our results further show that some judges could have misunderstandings on the differences between organic and experientially-based disorders.

This study had its limitations. Judges were contacted randomly via the created sample frame, but those who ultimately agreed to participate in this study may have already been interested in and conscious of mental health issues. For example, the majority of participants had previously worked as defense attorneys or public defenders, and all judges reported having completed training relevant to psychological and/or mental health evidence. It is possible that those judges who did not respond to our request for participation may have a different stance on sentencing mitigation based on bio-behavioral evidence and were, therefore, unresponsive, resulting in a participant selection bias. This is an important consideration given the vast numbers of defendants that are sentenced to prison and report experiencing at least one mental disorder (Abramsky et al., 2003; Fazel et al., 2016). While U.S. prisons are not designed to function as psychiatric or medical wards, some reports find that individuals with mental disorders occupy roughly one-fifth of all correctional facility beds (Bronson & Berzofsky, 2017; Fazel et al., 2016). It is thus important to understand how a wider population of judges may view mitigation in light of mental health evidence.

Moreover, this sample of 34 judges, while sufficient for within-subjects quantitative analyses, does not allow for the generalizability of the results to all U.S. judges. Additionally, considering the results of the power analysis, this study was slightly underpowered. While the sample was sufficient for the planned analysis of variances, it is possible that the mediation analysis would have yielded significant results with a larger sample. When it is not possible to obtain a larger sample, studies planning quantitative analyses of data obtained from hard-to-reach populations would be well advised to limit the number of comparisons during the design of their surveys.

Moreover, two methodological considerations should be noted. First, the hypothetical cases in the present study all described an aggravated assault offense committed during a traffic incident. However, other types of crime may differentially influence how a mental health defense is viewed by judges. For example, prior studies show that the type of crime influences views on the relevance of factors such as remorse and mental illness evidence (Zhong et al., 2014) and different types of offenses have also been shown to influence essentialist biases closely linked to perceptions about mental disorders (Xu et al., 2021). The results of the present study may thus not be readily generalizable to different crime categories. Additionally, the types of sentences that judges could select were treated as a continuous variable by assigning a severity ranking. While based on the proportionality principle, imprisonment can be considered more severe than probation and treatment, this ranking is not necessarily objective under all circumstances. For example, treatment-based sentences have been described under some circumstances as more severe than imprisonment (Holmen, 2021; Williams, 2023) and judges that are strongly opposed to incarceration may assign a heavier weight to the option of imprisonment, which would render the ranked variable as ordinal, rather than interval in those cases. The present study did not describe a treatment option as severe as mandatory rehabilitation or civil commitment, and judges were at liberty to select minimal imprisonment lengths which allowed for some nuance in the option of imprisonment; future studies should be similarly cautious in inferring punishment severity from different sentence types.

In order to influence criminal justice policy and improve outcomes for individuals with mental disorders, a better understanding of sentencing decision-making practices is needed (Kaiser & Holtfreter, 2016). Overall, the present study provides some insight into judges' decision-making process when dealing with different mental health disorders. Our findings suggest that some judges may overlook the promotion of rehabilitation as a viable solution for behavior modification, while also opting for custodial sentencing options at significantly higher rates than treatment. However, empirical research shows that treatment is effective in reducing recidivism both for acquired and innate behavioral disorders (Holloway et al., 2006; Lamberti, 2007; Lowder et al., 2018). Still, many U.S. jurisdictions do not have treatment programs that can be used as standalone sentencing options, and therefore, judges may not consider treatment as a feasible sentencing option (Douds & Ahlin, 2018; Goss, 2008; Monahan et al., 2018). Expanding treatment programs available to all courts would be one critical development towards better integrating treatment into criminal sentencing practices (Lowder et al., 2018). A shift towards promoting rehabilitation, when behavior is influenced by mental disorders, not only aligns with existing empirical evidence, but it also holds the potential to foster societal reintegration, reduce recidivism rates, and contribute to a more effective criminal justice system.

The findings of this study also underscore the necessity for policy changes aimed at enhancing scientific education within the criminal justice system. While most courses offered to judges include some scientific training, mental health training tends to be broad and primarily focus on legal aspects, such as the admissibility of certain types of evidence–but not on addressing common misconceptions about mental illness (Lyngar, 2017). This study's results indicating that some judges may be more punitive towards defendants with trauma as compared to those with disorders that are perceived as more innate or organic, potentially highlighting a knowledge gap. Indeed, studies have shown that even judges in Mental Health Courts lack formal education about evidence-based practices for trauma-related disorders (Brown et al., 2023). Moreover, the present study aligns with previous research showing that judges may prefer biological, over psychological, evidence and be less interested in statistical or empirical social science research (Redding et al., 2001). New initiatives should focus on integrating comprehensive training programs that equip judges with a nuanced understanding of mental disorders: both in terms of their impact on behavior and with regard to the efficacy of treatment options. This could entail updating current educational curricula to address the influences of different types of mental disorders on criminal or antisocial behaviors, as well as including evidence-based research insights on the treatability of different mental health problems. By fostering scientific literacy, the judiciary could be better equipped to make more informed and effective decisions in sentencing so that outcomes may be better aligned with existing empirical work.

In conclusion, this study found that scientific explanations of behavior may significantly influence sentencing decisions, with evidence of an organic brain disorder diminishing support for retribution and mitigating sentencing outcomes. Evidence of an acquired trauma-related disorder did not yield similar effects, and rehabilitation was not a central consideration in judges' appraisals of bio-behavioral scientific evidence. These results have broader implications, suggesting a need for policy changes that could expand treatment programs and promote scientific education within the criminal justice system. By shedding light on how judges evaluate scientific evidence and highlighting gaps in their knowledge, this research can inform policymakers and judicial training programs about specific training needs for decision-makers in the criminal justice system. Developing scientific comprehension within criminal courts could lead to more informed and equitable sentencing decisions for individuals with mental health disorders who become involved in the criminal justice system. Indeed, existing literature suggests that the prison environment can further aggravate symptoms of mental disorders, while also being ineffective in reducing recidivism (Abramsky et al., 2003; Bales & Piquero, 2012; Padfield & Maruna, 2006). If the knowledge that individuals' behavior is biologically influenced can help to reduce judicial punitiveness and support for imprisonment, the entire criminal justice system's response may be more effective in rehabilitating behavioral problems and preventing future offending.