Abstract

Introduction: Risky sexual behaviors in adolescence are associated with negative health and psychological functioning outcomes. Although the association between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors is well established, addressing these problems requires understanding the mechanisms that help explain this association. Adolescent attachment, while related to risky sexual behavior, has not been extensively explored as an outcome of childhood externalizing problems. The two objectives of this study were to explore the links between parental and peer attachment and risky sexual behaviors and to examine the mediating effect of attachment on the links between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors. Methods: Five hundred and ninety‐eight French‐Canadian adolescents (46.2% girls), Mage at T1 = 13.23; Mage at T2 = 14.28; Mage at T3 = 17.35) participated in this longitudinal study. Results: The quality of parental attachment at T2 was significantly and negatively associated with risky sexual behaviors 3 years later, at T3. More specifically, a lower quality parental attachment relationship was associated with having nonexclusive partners as well as with inconsistent condom use. Finally, parental attachment (T2) was a significant mediator between behavior problems (T1) and risky sexual behaviors (T3), but only for younger adolescents. Conclusions: Findings suggest that in addition to behavior problems in adolescence, the quality of parental attachment relationships may help in understanding risky sexual behaviors in adolescence.

1 | INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is often considered a “risky” period because of the higher probability of psychosocial or health problems (e.g., depression, behavior disorders, drug and alcohol use) compared with childhood or adulthood (Costello et al., 2011). It is also during this transitional period that many adolescents experience, for the very first time, love, romantic relationships, and physical intimacy and sexual intercourse, making it pivotal period for understanding romantic/sexual relationships. In terms of understanding the developmental nature of sexual behavior during this period, the Québec Health Survey of High School Students (EQSJS; Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2016–2017) showed that 33% of youth aged 14 years and over reported being sexually active, that is, having had oral, vaginal, or anal sex at least once in their lifetime, a proportion that increases over time. Statistics reported for the United States revealed a very similar situation: in 2019, 38% of high school students reported having had a sexual intercourse (i.e., penile‐vagina intercourse) and 27% were currently sexually active (i.e., had sexual intercourse at least 3 months before taking the survey) (US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). By 19 years of age, 70% of US adolescents have had intercourse (Martinez et al., 2011). Sexuality is a normal and expected aspect of adolescent development, and sexual activity during this period is not linked with poorer psychological functioning (Harden, 2014; Tolman & McClelland, 2011). That said, if sexual exploration during adolescence is normative and can be a sign of healthy development, some adolescents engage in sexual behaviors that may place them at risk for physical and psychosocial outcomes.

1.1 | Risky sexual behaviors

Sexual health refers to “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well‐being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sex experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence” (World Health Organization, 2006). Risky sexual behaviors have been the focus of considerable research because of their potential negative consequences for adolescents' sexual health (Chawla & Sarkar, 2019), which refers and can include early sexual intercourse, having multiple or nonexclusive partners and not using contraceptives such as condoms, all behaviors which have been linked to heightened health risk either alone, or because they are associated with an increased likelihood of other risky sexual behaviors. To start, not using contraceptives, and particularly condoms, increases the subsequent likelihood of contracting a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and adolescent pregnancy (Diamond & Savin‐ Williams, 2011; O'Donnell et al., 2001; Rotermann, 2008). Early sexual initiation is also considered a sexual risk behavior due to its association with a higher risk of engaging with multiple partners, STIs (Kugler et al., 2017) and not using condoms (Osorio, 2017), as well as with an increased likelihood of presenting mental health problems (Wesche et al., 2017). Having multiple partners, and particularly concurrent nonexclusive partners, also increases the likelihood of STI, especially in the absence of condom use (Gorbach & Holmes, 2003; Gorbach et al., 2005), as increasing numbers of partners also increases likelihood of being exposed to a potentially infected partner (Boislard et al., 2009). Research has also directly linked having multiple sexual partners during adolescence with early sexual debut and unsafe sexual practices (Christianson et al., 2007; Leishman, 2004; Kuortti & Kosunen, 2009; Santelli et al., 1998). Together, these findings highlight the relevance of looking at condom use, early sexual debut and multiple and/or nonexclusive sexual partners as indicators of sexual risk behavior.

1.1.1 | Externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors

Some theoretical frameworks of externalizing behavior problems link these problems with risky sexual behaviors in adolescence. For example, Jessor and Jessor's theory of the general deviance syndrome (1977), defined as an increased propensity for deviance and rejection of social norms, laws, and conventions, suggests that risky sexual behaviors co‐occur with other behavior problems, such as delinquent activities or substance use during adolescence. This co‐occurence reveals a common propensity to deviate from social norms (Jessor et al., 2003). Similarly, Moffit and Caspi (2001) suggest that adolescents' behavior problems fall into one of three broad categories of factors that help explain risky sexual behaviors, which are inadequate parenting, neurocognitive problems, and temperament and behavior problems. In the last decades, the association between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors was also supported by empirical studies that have linked externalizing behavior problems, such as aggressiveness, antisocial behaviors, and drug and alcohol use, to risky sexual behaviors in adolescence (Boislard et al., et al., 2009, 2013; Caminis et al., 2007; Holliday et al., 2017). In fact, the study by Boislard et al. (2009) showed that antisocial behaviors partly explain the adoption of risky sexual behaviors in adolescence, that is, nonsystematic condom use and a higher number of lifetime sexual partners. Holliday and colleagues (2017) also observed a significant association between conduct disorders and engagement in risky sexual behaviors defined as having many sexual partners, not using condoms, and using drugs before sexual intercourse. Along the same lines, results showed that adolescents having high trajectories of behavior problems and of drug and alcohol use in high school are more likely to start having sex early, to use condoms irregularly or occasionally, to receive money in exchange for sexual services, or to contract an STI.

Whereas an association between externalizing behavior problems and certain risky sexual behaviors has already been established, less is known about the mechanisms that explain this association. One study by Ramrakha et al. (2007) indicated that a poor‐quality parental attachment relationship, characterized by low levels of trust and communication and a high level of alienation, partly explained the association between children's antisocial behaviors and early sexual initiation. The study of Fergusson and Woodward (2000) showed that the association between girls' behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors (i.e., multiple sexual partners and teenage pregnancy), was mediated by a poor‐quality parental attachment relationship. The small number of studies pertaining to this issue and certain characteristics of these studies (e.g., risky sexual behaviors considered or specificity of the sample) makes it difficult to arrive at definitive conclusions regarding the mediating effect of parental attachment on the links between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors. Yet, the contribution of attachment, defined as an affectionate bond or tie between an individual and an attachment figure which provides the individual with the sense of security they need to explore their environment and thus support optimal development (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1979), may be particularly pertinent in addressing sexual behavior. Although the quality of attachment relationships, especially parental attachment, is often thought as a determinant of behavioral problems (Kerns & Brumariu, 2016; Madigan et al., 2016), attachment relationships are also impacted by the presence of behavioral problems (Allen et al., 2004; Brook et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2013; Therriault et al., 2021), suggesting that the association between the quality of attachment relationships and behavioral problems is likely to be bidirectional. Indeed, the behaviors associated with externalizing behaviors, such as aggressive, oppositional, and hostile behaviors, have the potential to make the parent–adolescent relationship more conflictual, thus undermining the quality of the attachment relationship.

1.1.2 | Attachment to parents and peers and risky sexual behaviors

Whereas the link between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors is well established, research linking attachment and risky sexual behaviors is less clear. Attachment theory (Ainsworth, 1979; Bowlby, 1969) provides a relevant framework for understanding the relational dynamics underlying sexual behavior (Dewitte, 2012). During adolescence, individuals explore environments outside of their family (notably through sexuality), a natural process that leads to sexual maturity. A secure parent–adolescent attachment relationship can also contribute to the development of emotional, relational, and behavioral skills (Delgado et al., 2022), which have the potential to lead to a safer and healthier sexuality. Moreover, adolescents who have high‐ quality attachment relationships with their parents are proposed to be better equipped to cope with this developmental task compared with those who have lower‐quality relationships, due to the link between attachment quality and internal working models of healthy relationships (Potard et al., 2017). More specifically, the internal working models developed by individuals during childhood are proposed to have a strong influence on cognitive, social, and behavioral responses in intimate relationships, including sexual interactions (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Individuals' positive beliefs about themselves and about others as well as their effective emotion‐regulation strategies are proposed to enable them to approach sex in a relaxed state of mind, free of worry and of defensive distortions. Individuals with positive attachment would subsequently not use sex to satisfy their attachment needs and would enjoy it for the pleasures it provides (Shaver & Hazan, 1988; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2006).

The literature available to date on the associations between adolescents' attachment insecurity and risky sex has some limitations. Most studies conducted to date have been carried out with samples that vary widely in age (i.e., from early adolescence to young adulthood) with relatively few focusing on early adolescence. Many of these studies, moreover, have focused on the link between attachment and sexual behaviors exclusively among girls and women. Researchers interested in sexuality in adolescence tend not to consider the relational processes when examining sexual behaviors, whereas those interested in adolescents' social relationships rarely examine the impact of these relationships on adolescent sexuality (Dewitte, 2012). Yet, one theoretical model explaining risky sexual behaviors, proposed in the early 2000s by Taylor‐Seehafer and Rew, suggests that adolescents' risky sexual behaviors could notably be explained by environmental factors, such as poverty, social isolation, cultural norms, academic experience, but also adolescents' relationships with members of their family and with their peers, including attachment relationships. This theoretical model thus suggests that the quality of parental and peer attachment relationships could be associated with adolescents' risky sexual behaviors. This theory is also supported by the model proposed by DiClemente et al. (2007) which suggests that risky sexual behaviors are explained by family and peer relationships (which include attachment relationships).

Parental attachment and risky sexual behaviors

The few empirical studies linking parental attachment relationships to sexual behavior indicate that a poorer‐quality attachment is cross‐sectionally or longitudinally associated with riskier sexual behaviors, a link typically stronger among girls than boys (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Feeney et al., 2000; Kobak et al., 2012). Anxiety experienced in attachment relationships is also associated with less condom use, more unprotected sex, and a higher propensity to consent to unwanted sexual activities (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Feeney et al., 2000). For their part, Kobak et al. (2012) reported that a preoccupied‐type attachment is associated with a higher number of risky sexual behaviors (i.e., sex with promiscuous partners, multiple sexual partners, and history of STI) in adolescent girls. They observed no significant association between a detachment‐type attachment and risky sexual behaviors, contrary to Sprecher (2013). However, this last study was conducted with a sample of adults, which could explain these divergent results. In their longitudinal cohort study, Reyes et al. (2021) showed that children of mothers with lower maternal attachment at 9 months had 23% increased odds of multiple risky behaviors, such as risky sexual behaviors, at 17 years old. For their part, Kahn et al. (2015) showed in their study conducted with young adolescents, that the association between parental attachment and risky sexual behaviors, such as early sexual initiation and nonuse of condoms, was indirect and explained in part by the effect of attachment on impulsivity in decision making.

A recent meta‐analysis (Kim & Miller, 2020) on adult attachment style and risky sexual behaviors also suggested that insecure attachment styles, particularly attachment anxiety, is related to risky sexual behaviors. The results showed that attachment anxiety is associated with having multiple partners and engaging in condomless sex whereas attachment avoidance is associated with having multiple partners only. It is important to note, however, that this meta‐analysis included empirical studies that looked at attachment to parents, but also studies that looked at romantic attachment. This meta‐ analysis also suggested that the association between attachment and risky sexual behaviors may vary according to the age of the participants, the correlation between attachment anxiety and having multiple partners becoming stronger as the age of participants increased.

While these findings suggest that less adaptive attachment styles are associated with higher levels of risky behavior, a secure attachment to parents should be predictive of an absence of risky sexual behaviors or of a healthier sexuality. Sentino et al. (2018) review on the association between attachment and girls' (12–21 years old) sexual behaviors found that overall, a secure attachment acted as a protective factor against engaging in risky sexual behaviors. While existing theory and some existing research link attachment style with risk sexual behavior, other work shows no direct link between quality of parental attachment relationships and risky sexual behaviors. Both Owen and colleagues (2010), who focused on hooking up (i.e., a range of physically intimate behaviors that occurs outside of a committed relationship), and Lohman and Billings (2008), who focused on early sexual initiation, multiple sexual partners and unprotected sex among boys found no link between attachment and risky sexual behavior. These nonsignificant results could be explained by the type of sexual behaviors examined in the first study and by the sample composed exclusively of boys in the second one. Hamme Peterson et al. (2010) found an absence of a direct association between the quality of parental attachment relationships and the adoption of risky sexual behaviors (i.e., multiple sexual partners, contraceptive misuse, and early sexual initiation). Their results supported and indirect association, via drug and alcohol use. Finally, Flykt et al. (2021) found no association between attachment profiles, based on parent, peers and romantic attachment, and adolescents' sexual risk‐taking. In conclusion, the results concerning the link between the quality of parental attachment and risky sexual behaviors remain divergent (perhaps due to the heterogeneity of the samples in terms of age), but still suggest that parental attachment could be associated with risky sexual behaviors, particularly among girls.

Peer attachment and risky sexual behaviors

To date, very few studies have focused on the direct associations between peer attachment and risky sexual behaviors. Yet, peers seem to be a significant source of influence when it comes to early risky sexual behaviors in adolescence, as proposed in the theoretical model by Taylor‐Seehafer and Rew (2000), who identified peers as an environmental variable associated with the development of risky sexual behaviors. Boislard et al. (2009) showed that keeping company with deviant peers is associated with engagement in risky sexual conduct. One study showed that adolescents who had more sexually active friends, or who thought their friends were more sexually active were also more likely to be sexually active (Sieving et al., 2006). These studies suggest that the quality of peer attachment relationships could also act as a predictive factor for risky sexual behaviors. On the other hand, Flykt et al. (2021) did not observe association between attachment profiles, based on parent, peers and romantic attachment, and adolescents' sexual risk‐taking.

In sum, the presence of a significant association between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors has been well demonstrated in recent decades. However, a gap in the literature exists about the importance of relational variables in explaining this association, beyond suggesting that parental attachment could play a role. Theoretically, it is plausible that attachment could be associated with risky sexual behaviors, considering the relational aspect underlying this type of behavior. Yet, the studies available to date do not enable clear conclusions to be drawn about the relationship between parental and peer attachment in adolescence and risky sexual behaviors. In addition, based on previous results, it seems possible that these associations could vary according to the adolescent's sex and the adolescent's age. Previous research has demonstrated stronger associations in girls between parental attachment and risky sexual behaviors (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Feeney et al., 2000; Kobak et al., 2012) and divergent results regarding the links between these two variables are observed in younger versus older adolescents (Kobak et al., 2012; Sprecher, 2013). Kim & Miller's (2020) meta‐analysis also suggests that adolescent age may act as a moderator of the association between attachment and risky sexual behavior in adolescence, such that older adolescents report more of a link between attachment anxiety and having multiple partners than younger adolescents. These results are moreover consistent with other studies showing how the importance of attachment relationships with parents changes over the course of development. Indeed, Ma and Huebner's study (2008) found that younger adolescents reported placing greater importance on attachment relationships with their parents than older adolescents. Thus, attachment relationships may play different roles across adolescent development, underscoring the need to explore the moderating role of age.

1.2 | Present study

The existing literature suggests that externalizing behavior problems are associated with insecure attachment quality (e.g., Allen et al., 2004), and are linked to higher rates of risky sexual behavior (e.g., Boislard et al., 2009, 2013; Holliday et al., 2017; Jessor et al., 2003). Poor attachment quality, moreover, is one of the major predictors of risky sexual behavior (see Kim & Miller (2020) for a literature review). A gap exists in the literature, however, as to the extent that the link between externalizing problems and risky sexual behavior is explained by poor attachment. A better understanding of the role of attachment relationships in the association between externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors could lead to the identification of promising intervention targets that could reduce the likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviors, particularly in adolescents with behavior problems. In this study, we pursued two main objectives to address this gap. The first was to explore the links between the quality of parental and peer attachment relationships in adolescence and risky sexual behaviors 3 years later, while controlling for the adolescents' sex and age. These control variables have been retained because of research showing that these two variables can have an effect on risky sexual behaviors (Baams et al., 2015; Cubbins & Tanfer, 2000). Low‐quality attachment to parents and peers was expected to be associated with more risky sexual behaviors. The second objective was to examine if parental and peer attachment mediated the links between externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors, and to examine if the mediating effect was moderated by the adolescent age (while controlling for sex and age, the initial parental and peer attachment quality and the attachment figure). It was expected that attachment to parents would mediate the association between externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behavior.

2 | METHOD

2.1 | Participants

Data were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal project pertaining to sex differences in the evolution of externalizing behavior problems. Participants were selected with the help of the school boards of four administrative regions in Québec (Montréal, Montérégie, Estrie, and Capitale‐Nationale). The participants (N = 744; 46.8% girls) were recruited in 155 elementary schools between 2008 and 2010. More than 50% of participants were approached because of the presence of externalizing behavior problems necessitating school‐based services. The longitudinal study has reached its 10th annual measurement time in 2017–2019 (N = 650; mean age = 17.35 years). For the purposes of the present study, the measurements considered were those taken during adolescence, when adolescents were, on average, 13.23 years (T1 – 2013–2015), 14.28 years (T2 – 2014–2016), and 17.35 years (T3 – 2017–2019). To be included in this study, participants had to have completed the risky sexual behaviors questionnaire at T3 (N = 630) and have available data on behavior problems at T1 and/or on attachment at T2. Data on parent and peer attachment at T0 (i.e., 12 months prior T1) were used to control for the initial attachment quality in the analyses.

The sample in this study was thus composed of 598 French‐Canadian adolescents (46.2% girls), mostly born in Canada (94.5%), who completed the questionnaire on risky sexual behaviors at T3 and who also had data at T1 on behavior problems and/or at T2 on attachment, which represents 94.9% of the potential sample of 630 participants. In total 45.2% lived with both biological parents, 23.6% lived in blended families, and 28.9% lived in single‐parent families. The mean annual family income reported at T1 was between CAN$60,000 and CAN$69,000. Among these adolescent boys and girls, 58.0% reported being sexually active by responding “yes” to the question Have you ever had consensual sexual intercourse with penetration? All the participants were included in the analyses, where abstinence was treated as an absence of risk. Participants did not differ from dropouts in terms of proportions of boys and girls (χ2 (1) = 0.47, p = .49) and mean levels of annual family income (t(734) =−0.845, p = .40), age (t(742) = 0.93, p = .36) and level of behavior problems (t(244.87) = 0.019, p = .99) at their recruitment.

2.2 | Procedures

The data in this study covered a 5‐year period, and were collected during home visits conducted by research assistants. For each measurement time, an interview (60–120 min) was conducted separately with the responding parent as well as with the adolescent. Before the first assessment, parents and adolescents received a full description of the study. Parents signed an informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ethics for Research in Education and Social Sciences of the Université de Sherbrooke (Québec, Canada). The consent form included the permission to obtain information from the teacher about the adolescent's behaviors in school. Adolescents also had to give their verbal consent. This procedure was repeated for each wave of data collection. Each of the participants received financial compensation for the time they devoted to the study.

2.3 | Measures

2.3.1 | Externalizing behavior problems

The Externalizing Problems scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (ASEBA; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used at T1 to assess the presence of externalizing behavior problems. This scale consists of 35 items (e.g., Gets in many fights, Hangs around with others who get in trouble, Screams a lot, Temper tantrums or hot temper) for which the parent indicates whether it matches the youth's situation on a 3‐point Likert‐type scale (0 = does not apply to 2 = always or often true). In this study, the T score was used. The psychometric properties reported for this tool are excellent (Achenbach, 1991). For the sample used for this study, the Cronbach's ⍺ obtained was .94, demonstrating excellent internal scale consistency for this scale.

2.3.2 | Attachment

We used the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) at T0 and T2 to assess the quality of the attachment relationships. The two versions (parent and peers) of this inventory were used at each measurement times. Each version included 25 items and measure adolescents' perceptions of their parental and peer attachment relationships on three scales: trust (10 items, e.g., I trust my parent/my friends), communication (parent = 9 items/peers = 8 items; e.g., My parent encourages/my friends encourage me to talk about my troubles), and alienation (parent = 6 items/peers = 7 items; e.g., I would have liked to have a different parent/different friends). This tool also provides a global score for the quality of attachment relationships for each version (parent and peers), calculated by adding the two positive scales (trust and communication) and subtracting the alienation scale. The global scores were used in this study at T0 and T2 (scores obtained at T0 were used as control variables for the second objective while score at T2 were used as independent variables for the first objective and as the mediator for the second objective). For each item, the adolescents must indicate how well the statement matches what they feel on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale (0 = not at all to 4 = very much so). For the parent version, the adolescents' answers must refer to the main respondent in the study, most often the mother. In this study, Cronbach's ⍺ proved satisfactory, for the parent (T0 = 0.76; T2 = 0.82) and peer (T0 = 0.83; T2 = 0.85) versions alike.

2.3.3 | Risky sexual behaviors

Adolescents' risky sexual behaviors were measured at T3 using questions taken from the 1999 Quebec Health and Social Survey of Children and Adolescents (Institut de la statistique du Québec, 1999), which measures sexual experiences (e.g., having consensual sexual intercourse with penetration, age at first intercourse, number of stable and nonexclusive partners, condom use, being [or having been] pregnant or impregnating a girl, and having an STI). In this study, four risky sexual behaviors were retained: adolescent's age at first sexual intercourse (<14 years), number of sexual partners (>3), having nonexclusive sexual partners (yes or no), and nonuse of condoms during intercourse with penetration, where adolescents reported not using condoms 100% of the time received a score of 1 for this indicator, because after a single unprotected intercourse, the risk increases regardless of the adolescent's habitual condom use (Boislard et al., 2009). Pregnancy and STI indicators could not be used in this study due to their low occurrence in our sample. For every indicator, each participant received a score of 0 or 1 (absence/presence). These indicators were first used individually (dichotomously), and then summed to obtain a global risk score, varying from 0 to 4, where a high score indicated a higher level of risky sexual behaviors. Abstinent adolescents, that is, those who have not had intercourse by at T3, all received a score of 0. They represented 40.9% of the sample. The risk thresholds used for age (under 14 years) and for number of partners (more than 3) are consistent with those used in other studies on risky sexual behaviors (Boyce et al., 2003; Bradshaw et al., 2010; Rotermann, 2012).

2.4 | Statistical analyses

2.4.1 | Preliminary analyses

First, we conducted the descriptive analyses (minimum, maximum, mean, and SD) using SPSS 25.0 software (IBM Corp. Released, 2017). Second, we performed a negative binomial regression linking behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors using MPlus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2014). This analysis helped confirm that the association between these variables reported in previous studies, was also observed in the present sample. This type of analysis was chosen over a linear regression to overcome the nonnormal distribution (Poisson distribution) of the dependent variable. In fact, many participants obtained a score of 0, either because they abstained from sexual behavior more broadly or because they did not report any risky sexual behaviors.

2.4.2 | Main analyses

To test the first objective—to examine the association between the quality of parental and peer attachment relationships and engagement in risky sexual behaviors 30 months later—we conducted negative binomial regression analyses, using MPlus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2014), while considering the global scores for parental and peer attachment as independent variables and their contribution to risky sexual behaviors. The negative binomial regression was retained, again to overcome the dispersion problem. We then performed logistic regression analyses using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp. Released, 2017) for each of the four indicators of risk individually.

To test the second objective of the study, which was to examine the mediating effect of parental and peer attachment on the links between externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors, and to examine if the mediating effect was moderated by the adolescents' age, we tested two moderated mediation models through structural equation modeling (SEM) in MPlus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2014). A Montecarlo numerical integration approach was used to retain all 598 participants who had valid data on risky sexual behaviors at T3. In the first model, the global score for risky sexual behaviors was included as the dependent variable, while parental and peer attachment were included as the mediators. To account for the skewed distribution, the risky sexual behaviors variable was designated as a count variable in the SEM model. Adolescent's age at T3 was included as a moderator. In the second model, the four risky sexual behaviors were included as the dependant variables while attachment was included as the mediation variable. Adolescent's age at T3 was also included as a moderator. Both models included behavior problems as the independent variable and were adjusted for adolescent's sex and age, attachment quality at T0 as well as for attachment figure (for parental attachment only). In both cases, a maximum likelihood estimator, robust to nonnormality (MLR) was used to perform the analyses.

3 | RESULTS

3.1 | Descriptives statistics

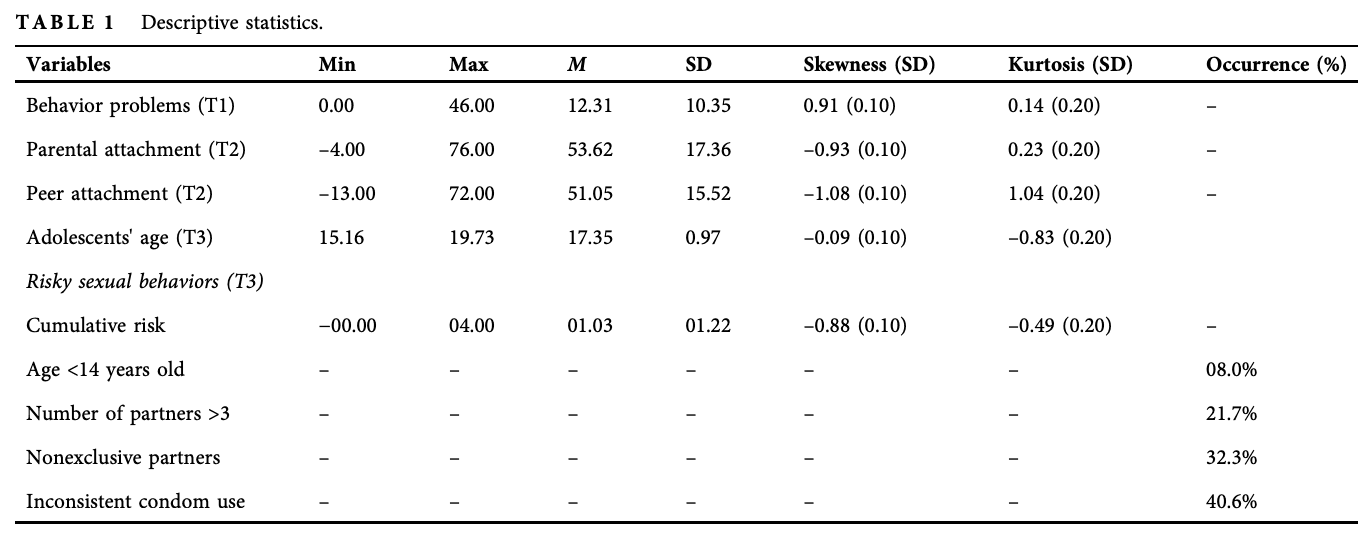

The descriptive statistics for the variables of interest are presented in Table 1. The first negative binomial regression analysis showed that externalizing behavior problems were significantly associated with risky sexual behaviors (β = .18; p < .01) when we controlled for the adolescents' sex and age.

3.2 | Associations between parental and peer attachment and the global score for risky sexual behaviors

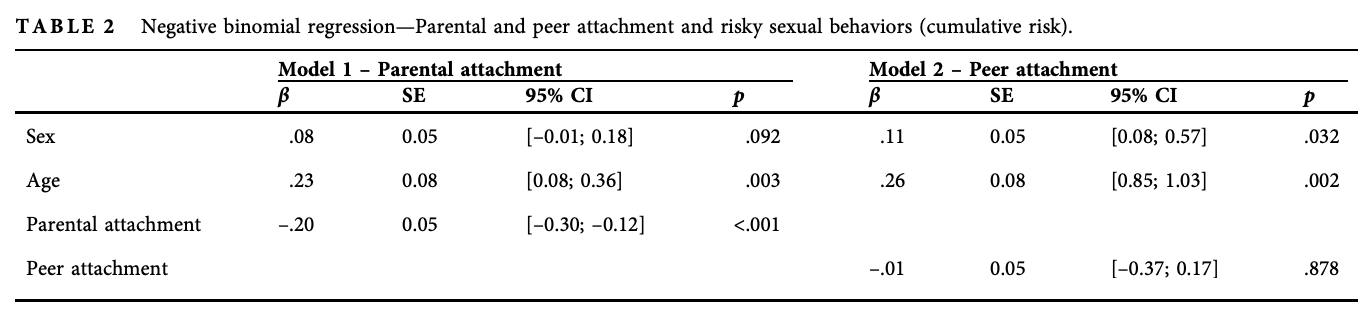

We conducted a negative binomial regression analysis (see Table 2) to predict the global score for risky sexual behaviors, integrating the global score of parental attachment as a predictive variable and controlling for the adolescents' sex and age. This model showed that a higher attachment score was associated with a lower score for cumulative risky sexual behavior (β = –.20; p < .001). The adolescents' age also contributed significantly to the model, with older adolescents (β = .23; p < .01) reporting a higher global score for risk.

In a second negative binomial regression analysis (see Table 2), we replaced the global score of parental attachment with the global score of peer attachment as a predictive variable, while controlling for the adolescents' sex and age. The analysis showed that the score for peer attachment did not act as a significant predictor (β = –.01; p = .878).

3.3 | Associations between parental and peer attachment and specific indicators of risky sexual behaviors

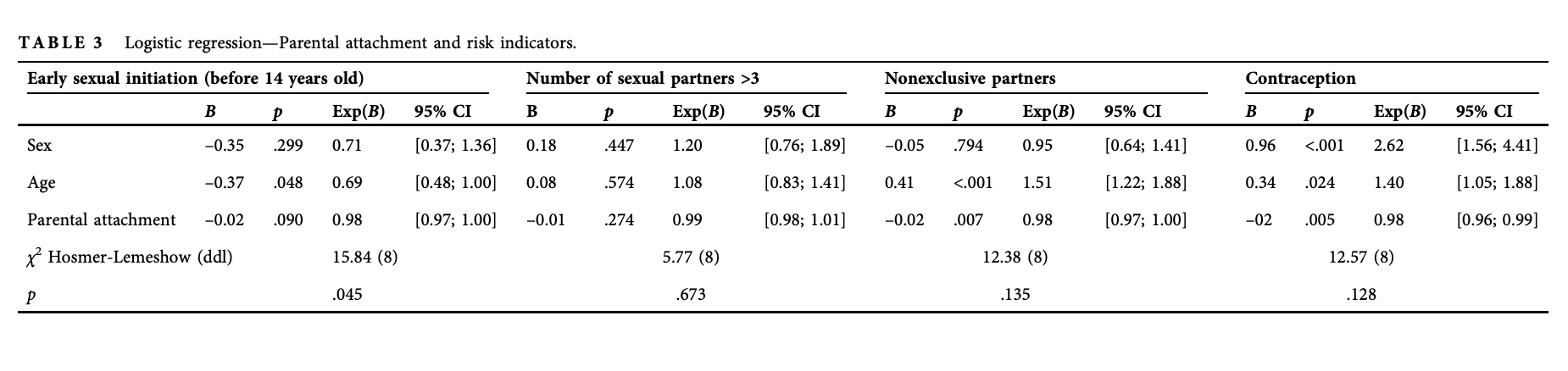

We then conducted logistic regression analyses separately for the four indicators of risk. We used the global score of parental attachment as a predictor, while controlling for the adolescents' sex and age (see Table 3). The results showed that the higher the quality of the parental attachment relationship, the lower the likelihood that adolescents reported nonexclusive partners (Exp(B) = 0.98; p < .01) and inconsistent condom use Exp(B) = 0.98; p < .01) respectively. Being older also reduced the risk of early sexual initiation (Exp(B) = 0.69; p < .05) and increased the risk of having nonexclusive partners and of using condoms inconsistently (Exp(B) = 1.51; p < .001; Exp(B) = 1.40; p < .05 respectively). Finally, being a girl increased the risk of inconsistent condom use during sexual intercourse (Exp(B) = 2.62; p < .001). The association observed between the quality of parental attachment and early sexual intercourse was found to be marginally significant (Exp(B) = 0.98; p < .10), suggesting that a good‐quality attachment reduces the risk of early sexual initiation.

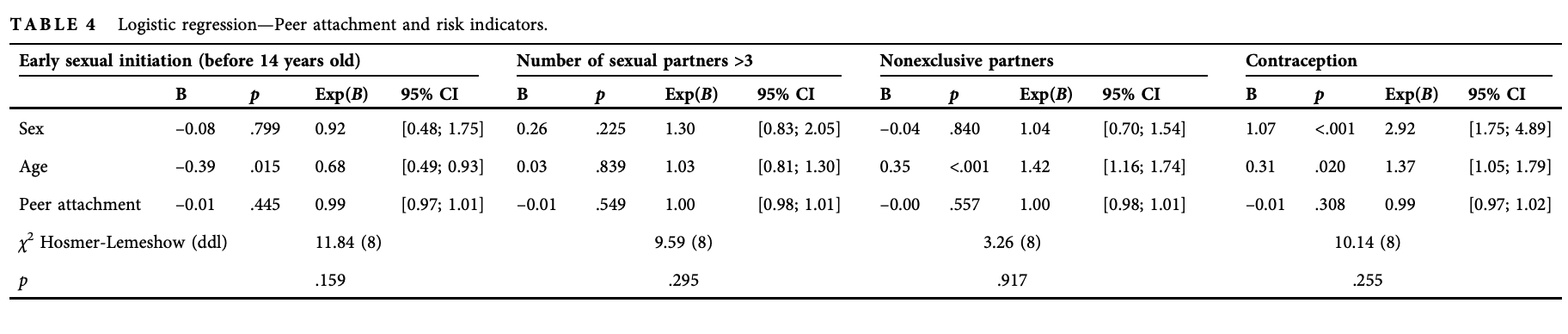

As shown in Table 4, no association was found between peer attachment and indicators of risky sexual behaviors.

3.4 | Moderated mediating effect of parental and peer attachment on the links between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors

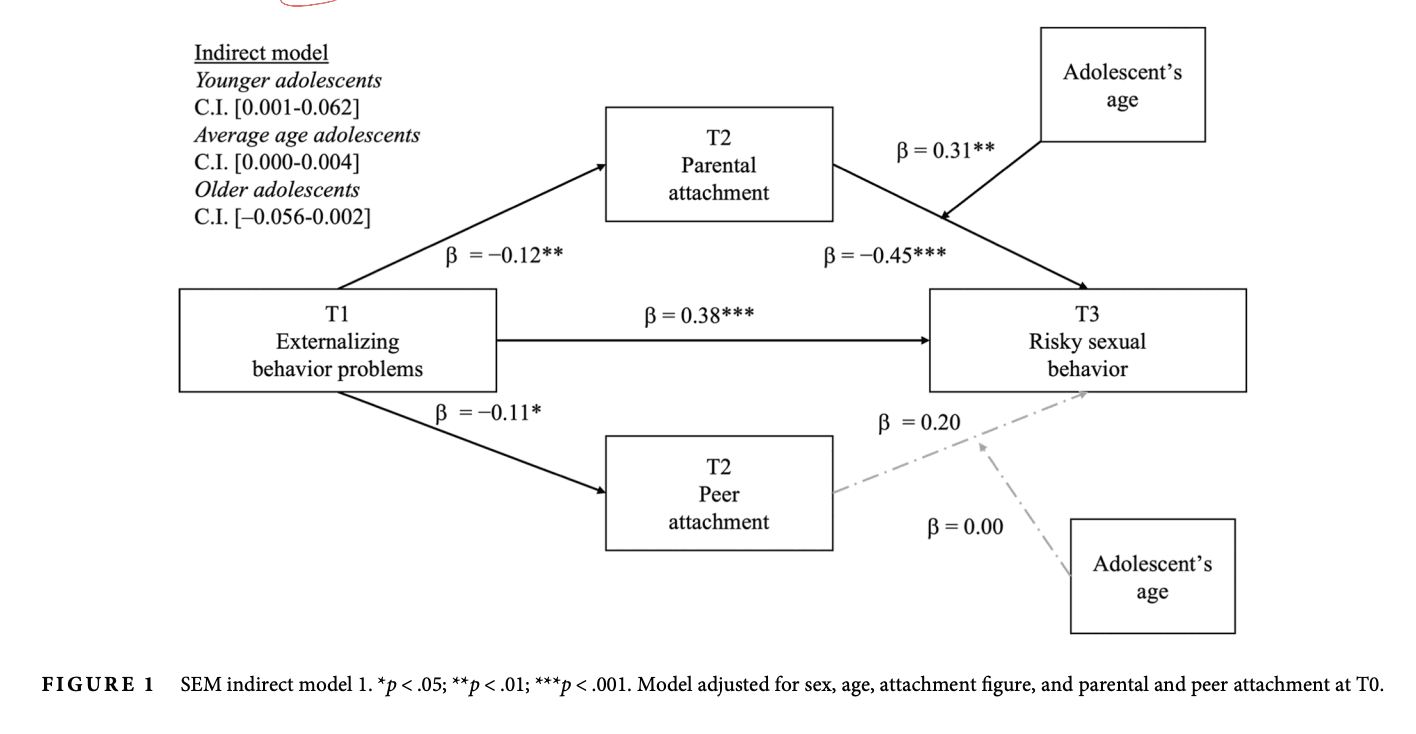

We examined the mediating role of the quality of parental and peer attachment relationships in the association between externalizing behavior problems and the adoption of risky sexual behaviors, moderated by the adolescents' age through the first SEM model (see Figure 1). We included the externalizing behavior problems as independent variable, parental and peer attachment as the mediating variables and the global score for risky sexual behaviors as the outcome variable. The results showed that the association between high levels of externalizing behavior problems at T1 and high levels of risky sexual behaviors at T3 was partly mediated by poorer‐quality parental attachment relationships at T2 (B = 0.002; 95% CI [0.001–0.004]; p < .05), while controlling for parental attachment at T0 (12 months before T1), sex, age, and the attachment figure. The indirect effect through peer attachment was not significant (B = –0.001; 95% CI [–0.002–0.000]; p = .189).

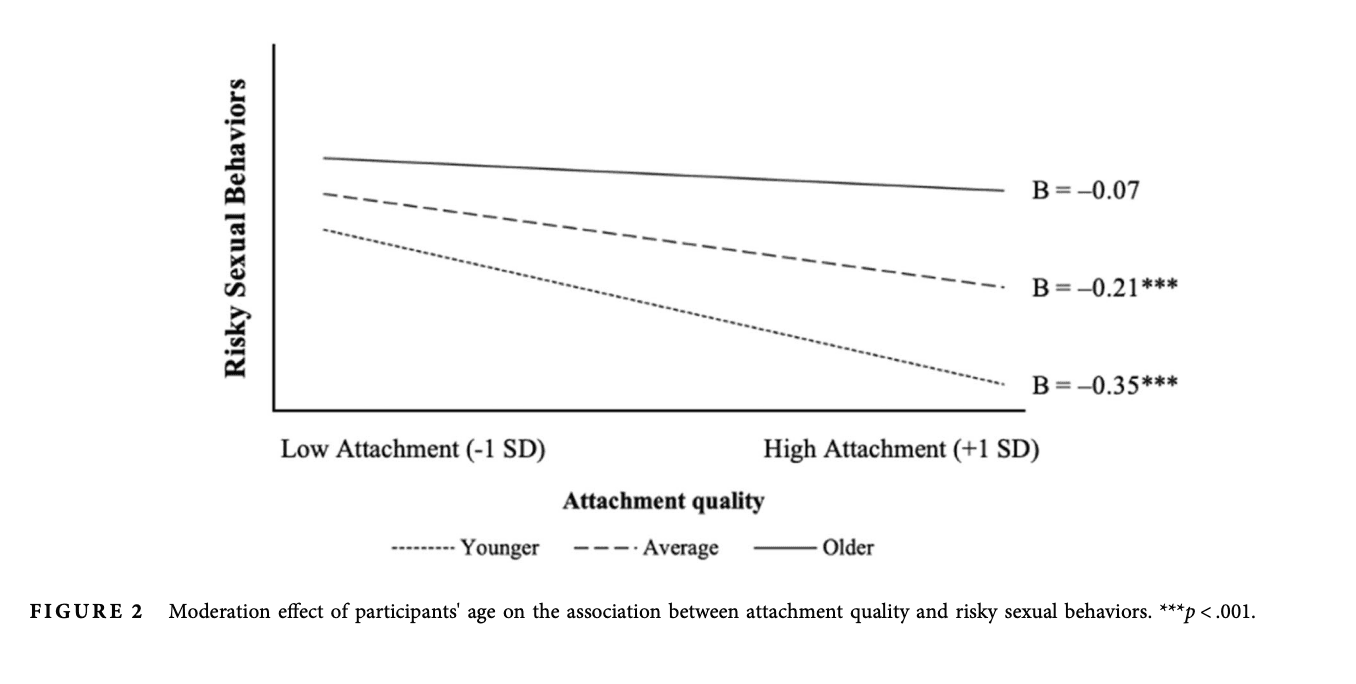

High levels of externalizing behavior problems were associated with poorer‐quality parental attachment relationships (β = –.13; p < .01), which were also associated with higher levels of risky sexual behaviors (β = –.45; p < .001). The mediation was significant but partial considering that the direct association between externalizing problems and risky sexual behaviors remained significant (β = .38; p < .001) after the inclusion of mediating variables. The results also showed that this significant indirect effect of externalizing behavior problems on risky sexual behaviors through parental attachment was true only for younger adolescents (one standard deviation below the mean, i.e., 16.36 years and younger; B = –0.35; p < .001) and those around average, that is, between 16.37 and 18.32 years (B = –0.21; p < .001). The indirect effect of externalizing behavior problems on risky sexual behavior through parental attachment was not significant for older adolescents (one standard deviation above the mean, i.e., about 18.33 years old and older; B = –0.07; p = .35) (see Figure 2).

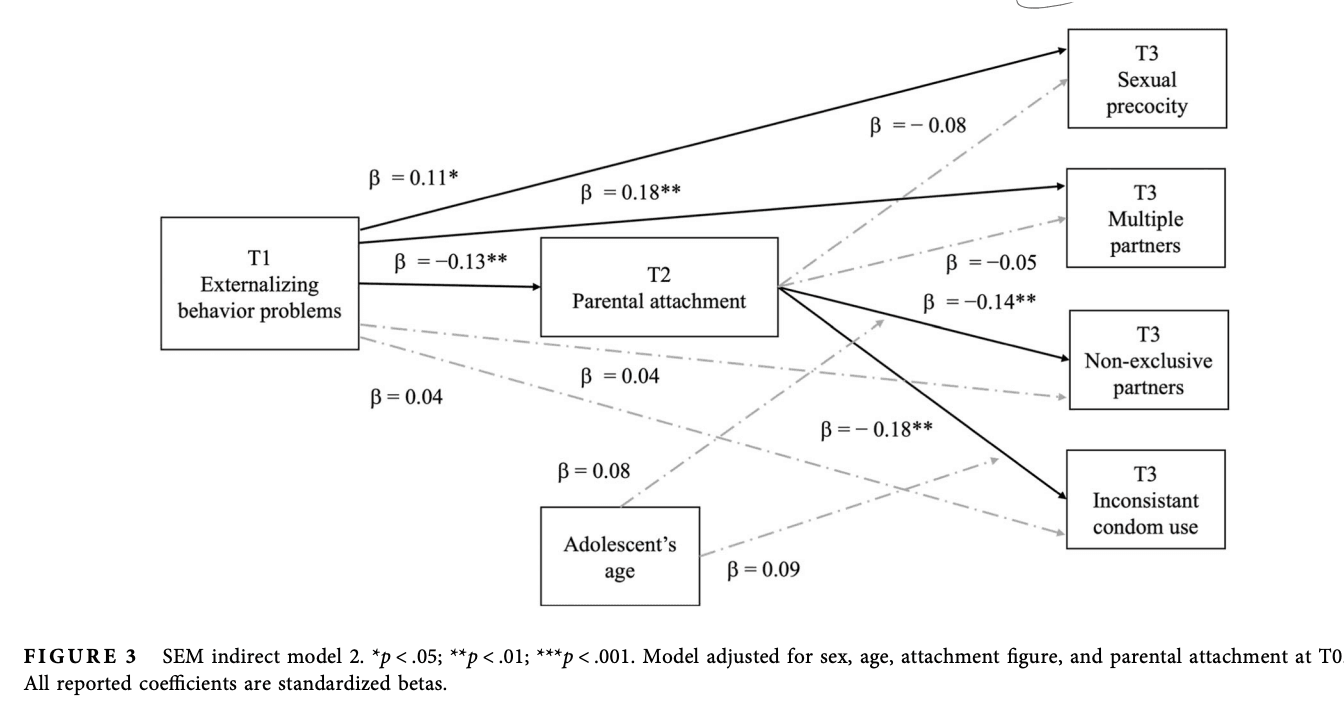

We also examined the mediating role of the quality of parental and peer attachment relationships in the association between externalizing behavior problems and the indicators of risky sexual behaviors, moderated by the adolescents' age, through SEM models. The second SEM model (Figure 3) examined the mediating effect of parental attachment in the relationship between externalizing behavior problems and the four indicators of risky sexual behaviors, as separate variables. We included the four indicators of risk as dependent variables, parental attachment as a mediator and externalizing behavior problems as the independent variable. Results showed that the association between high levels of externalizing behavior problems at T1 and nonexclusive partners and inconsistent condom use at T3 was totally explained by poorer‐quality parental attachment relationships at T2 (B = 0.001; 95% CI [0.001–0.002]; p < .05; B = 0.001; 95% CI [0.001–0.002]; p < .05; respectively), while controlling for initial parental attachment, sex, age, and the attachment figure. No moderation effect by the adolescents' age was found for these indirect associations (β = .08; p = .095; β = .09; p = .056, respectively).

The third SEM model, testing the mediating effect of peer attachment in the association between externalizing behavior problems and the four indicators of risky sexual behaviors, as separate variables, showed no indirect effect through peer attachment for any of the indicators of risk.

4 | DISCUSSION

This study had two objectives to fill the gap existing in the literature as to the extent that the link between externalizing problems and risky sexual behavior is explained by poor attachment. The first was to explore the links between the quality of parental and peer attachment relationships and risky sexual behaviors in adolescence. The second was to examine the mediating effect of parental and peer attachment on the association between externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors.

4.1 | Associations between attachment and risky sexual behaviors

Parental attachment relationship quality was correlated with global score for risky sex, suggesting that high‐quality parental attachment may be protective for adolescents with regard to this outcome. This result is consistent with some previous work (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Feeney et al., 2000; Kobak et al., 2012). More specifically, the current study linked a high‐quality parental attachment with more regular condom use, which is also consistent with the earlier studies (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Feeney et al., 2000). Current findings also linked high‐quality attachment with a lower probability of having sexual intercourse with nonexclusive partners, contrary to findings by Owen et al. (2010). However, the researchers in that study used a slightly older sample composed mainly of college students in their twenties, took a categorical approach to attachment (autonomous, avoidant, preoccupied), and focused particularly on the last two categories, which could explain these contradictory results. Future work is needed to clarify the current findings.

For several decades, secure parental attachment has been considered as an important protective and promotive factor for psychosocial functioning, with high‐quality attachment contributing to optimal developmental trajectories (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987; Kobak et al., 1993; Laible, 2007). A secure attachment could thus provide adolescents with the necessary tools—such as good self‐esteem—to make good decisions, to own their choices, and to thus adopt healthier sexual behaviors. This is consistent with one study showing that young adults who have low self‐esteem make riskier choices compared with those with higher self‐esteem (Wray & Stone, 2005). Another interesting avenue for explaining the association observed between parental attachment and risky sexual behaviors concerns the evolutionary hypothesis according to which attachment insecurity could lead to early puberty. Belsky et al. (2010), using the Strange Situation task, observed that adolescents identified as having had an insecure attachment at 15 months began and completed their puberty significantly earlier than adolescents with a secure attachment during childhood. Given that puberty is necessarily associated with sexuality (Fortenberry, 2013), it would be interesting to examine puberty as a potential mediator of the link between attachment and risky sexual behaviors. Finally, this association could also be partly explained by the internal working models developed by adolescents who have a secure attachment relationship with their parents. The mental representations that these adolescents develop over time influence how they perceive others, but also how they act in a given social situation (Bowlby, 1973), which could reduce their risk of engaging in risky sexual behaviors. Additional research on the processes that explain the association between attachment and risky sexual behaviors is required for a better understanding of this phenomenon.

The results also showed that the quality of peer attachment relationships was not significantly associated with the global score for risky sexual behaviors. As documented in some recent studies (Boislard et al., 2009; Sieving et al., 2006) and proposed by Taylor‐Seehafer and Rew (2000) theoretical model, peer influence on risky sexual behaviors could be explained via time spent with deviant peers or through their own sexual behaviors rather than through the quality of adolescents' peer attachment relationships.

4.2 | Mediating effect of attachment on the links between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors

The quality of parental attachment relationships also appeared to be a significant mediator of the association between externalizing behavior problems and the adoption of risky sexual behaviors, especially for adolescents under the age of 18. Thus, adolescents' behavior problems would have the potential to affect attachment relationships with their parents, accounting for initial levels of attachment, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Brook et al., 2012). Indeed, adolescents who engage in delinquent and aggressive behaviors may have difficulty developing or maintaining a close and healthy bond with their parents, as evidenced by poorer quality attachment relationships observed in this study. In turn, disrupted parent–adolescent attachment relationships would then place adolescents at greater risk of engaging in risky sexual behaviors, which is again consistent with previous studies (e.g., Kobak et al., 2012). This mediation model is supported by findings from Ramrakha et al.'s (2007) study. Although the mediation was partial, parental attachment accounted for some of the association between adolescents' externalizing behavior and their adoption of risky sexual behaviors. This finding represents an interesting theoretical advance, because it helps provide a better understanding of the mechanism behind the association between externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors (Boislard et al., 2009; Holliday et al., 2017; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Moffit & Caspi, 2001; Ramrakha et al., 2007).

The fact that this mediating effect was only observed in younger adolescents is developmentally interesting. The present study focused on the role of parental attachment (and peer attachment), which is recognized as playing an important role throughout development (McConnell & Moss, 2011). However, the indirect model only significant for adolescents under the age of 18 could be explained by the fact that the attachment relationship with the romantic partner might play a greater role than the attachment to parent in later adolescence. Indeed, parental attachment plays a more important role in younger adolescents than in older ones (Ma & Huebner, 2008), which may partially explain the current findings. Further studies that include attachment to romantic partner are needed to examine whether the mediation effect of parental attachment early in adolescence is gradually replaced by attachment to romantic partner.

Because the mediation effect was partial, however, these findings also highlight how a large portion of the variance of the association between externalizing behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors remains unexplained and that other mediators, or other explanatory mechanisms, could be involved. With respect to the mediating effect of parental attachment relationships in the associations between externalizing behavior problems and specific indicators of risky sexual behaviors, this study showed that the associations between externalizing behavior problems and nonexclusive partners and inconsistent condom use could be indirect, through attachment to parents. In both cases, more behavioral problems were associated with poorer attachment relationships, which in turn were associated with a greater risk of having nonexclusive partners and inconsistent condom use.

The fact that these mediation effects are not moderated by the age of the adolescents is surprising considering the results observed for the overall score of risky sexual behaviors. This result may in part be explained by the lower statistical power when risk indicators are examined separately, or may be explained by developmental changes in what constitutes sexual risk (i.e., inconsistent condom use may be less of a risk as adolescents age and use more consistent form of contraception). Further studies are therefore needed to validate these results.

4.3 | Strengths, limitations, future research avenues, and practical outcomes

This study has several strengths, including the longitudinal nature of the design and the use of a multi‐respondent approach. This study, however, has certain methodological limitations that are important to highlight. First, more than 50% of the sample consisted of children who, at study entry, presented behavior problems that were severe enough to warrant specialized services. While this approach provided greater variability in the externalizing behavior problems variable, the potential for generalizing the results to the general population is thus reduced. Furthermore, while a strength of the study was the use of multiple respondents for objective 2, for the first objective, all the questionnaires were completed by the adolescents themselves. In addition, some of the risk indicators included in the current study (e.g., inconsistent condom use) may be somewhat imperfect, in the sense that they may not always represent risky sexuality depending on context. For example, inconsistent condom use does not represent a health risk for monogamous couples using other forms of contraception. The instrument used to measure sexual risk behaviors also mostly documents heterosexual behaviors, which limits the generalizability of the results to members of the LGBTQ+ community, who may experience different risk factors for risky sexual behavior (i.e., homophobic discrimination, LGBTQ+‐specific family rejection). Moreover, considering the answer “no” to the question about consensual sexual intercourse with penetration as an absence of risk may have led to an underestimation of the actual level of risk, considering that the adolescents may have engaged in risky behaviors during nonconsensual intercourse or through other types of sexual behaviors. Finally, while adolescents who are sexually abstinent do fall into the larger category of youth not engaged in risky sexual behaviors, the decision to retain adolescents who were not sexually active may have influenced the study results by unintentionally conflating sexual risk with sexual opportunity. It could be relevant to replicate the present study in samples where all adolescents are sexually active.

Although attachment helps to partly explain the global score of risky sexual behaviors and some specific risk indicators, the effect of attachment is undoubtedly part of a complex, dynamic process involving other constructs. Nonetheless, this study addresses important gaps in the literature with regard to the links between externalizing behaviors, attachment, and risky sexual behavior. To gain further knowledge and a fuller, more accurate understanding of the influence of attachment relationships on adolescents' risky sexual behaviors, future work should examine the bidirectional interaction between externalized behavior problems and the quality of the adolescent's attachment relationships to better understand the dynamic nature of these associations. It could also be relevant to explore the concept of self‐esteem as a potential mediator of the relationship between attachment and sex. Furthermore, as suggested by Boislard et al. (2009) and by Moffit and Caspi (2001), adolescents' individual differences act as an important predictor of risky sexual behaviors. Future work examining other individuals' differences such as the dimensions of personality, for example, sensation seeking or impulsivity, in the association between attachment and risky sexual behaviors may help clarify the current findings. While this study used a variable‐centered approach, it may be worthwhile to use a person‐centered approach by creating risk profiles to further examine the associations between attachment and risky sexual behaviors. Furthermore, it could also be interesting to examine the links between attachment and online risky sexual behavior. In fact, online risky behaviors—such as talking about sex with an acquaintance or a stranger, sexting, sending compromising photos, and video chatting with strangers—are increasingly common among adolescents (e.g., Mori et al., 2022). Although these behaviors do not directly increase the risks for adolescents' physical sexual health, because they are not associated with a greater risk of contracting an STI or of unwanted pregnancy, they are nonetheless associated with high psychological and social risks for adolescents and may lead to major emotional distress or other problematic behaviors, such as alcohol abuse (Ševčíková, 2016). Finally, it could also be interesting to examine the mediation effect of attachment in the association between behavior problems and risky sexual behaviors through an auto‐regressive model, to better consider the direction of effects between externalizing behavior problems and the quality of attachment relationships.

From a clinical standpoint, the results of this study have made it possible to propose a new angle of approach for psychosocial caseworkers intervening with adolescents at risk of adopting risky sexual behaviors. Improving the quality of parental attachment relationships may become a prime intervention target in efforts to reduce the risk of engaging in a trajectory marked by the adoption of risky sexual behaviors. Indeed, effective interventions already exist that improve attachment quality between adolescents and their parents, such as the Connect Attachment programs (Moretti et al., 2017). The development of programs based on parent–adolescent communication or on the development of a relationship of trust is a promising avenue for decreasing the incidence of risky sexual behaviors (Coakley et al., 2017). The study results suggest also that these intervention targets could be even more relevant for adolescents with behavior problems, who sometimes represent a challenging group in terms of intervention. Indeed, intervention approaches that reduce externalizing problems in the long term are complex and costly (D'Amico et al., 2014; Rivenbark et al., 2018). Thus, complementary intervention targets, such as the quality of attachment relationships, becomes interesting for minimizing the possible consequences of these behavior problems for risky sexual behaviors.