Abstract

Rationale: Cannabis use among people with mood disorders increased in recent years. While comorbidity between cannabis use, cannabis use disorder (CUD), and mood disorders is high, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Objectives: We aimed to evaluate (1) the epidemiological evidence for an association between cannabis use, CUD, and mood disorders; (2) prospective longitudinal, genetic, and neurocognitive evidence of underlying mechanisms; and (3) prognosis and treatment options for individuals with CUD and mood disorders. Methods: Narrative review of existing literature is identified through PubMed searches, reviews, and meta-analyses. Evidence was reviewed separately for depression, bipolar disorder, and suicide. Results: Current evidence is limited and mixed but suggestive of a bidirectional relationship between cannabis use, CUD, and the onset of depression. The evidence more consistently points to cannabis use preceding onset of bipolar disorder. Shared neurocognitive mechanisms and underlying genetic and environmental risk factors appear to explain part of the association. However, cannabis use itself may also influence the development of mood disorders, while others may initiate cannabis use to self-medicate symptoms. Comorbid cannabis use and CUD are associated with worse prognosis for depression and bipolar disorder including increased suicidal behaviors. Evidence for targeted treatments is limited. Conclusions: The current evidence base is limited by the lack of well-controlled prospective longitudinal studies and clinical studies including comorbid individuals. Future studies in humans examining the causal pathways and potential mechanisms of the association between cannabis use, CUD, and mood disorder comorbidity are crucial for optimizing harm reduction and treatment strategies.

Introduction

Cannabis is one of the most widely used substances worldwide with 192 million people reporting past-year use in 2018 (UNODC 2020). Over the last decade, some countries including Australia, have managed to slow down the increase in cannabis use. Nevertheless, frequent cannabis use is still increasing in many countries in South America, North America and parts of Europe (UNODC 2020). Importantly, rates of cannabis use in individuals with depression appear to be increasing even faster than in people without depression. In 2005–2006, individuals with depression had 30% higher odds of being daily cannabis users compared to non-depressed individuals and this increased to 216% in 2015–2016 (Gorfinkel et al. 2020). In line with this, a recent meta-analysis found that 34% of medical cannabis users report alleviating symptoms of mood disorders as a motive for use (Kosiba et al. 2019). These high rates may reflect the growing belief that cannabis is beneficial for treating mood disorders (Bierut et al. 2017).

Mood disorders are characterized by alterations in emotions and mood (e.g. depressed or elevated moods) inconsistent with life circumstances, and the most common mood disorders include Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Bipolar Disorder (BD). A vast majority of people report relief of depressive symptoms during acute cannabis intoxication (Li et al. 2020). However, cannabis use is also associated with the worsening of mood disorder symptoms in a dose-dependent manner (Lev-Ran et al. 2013, 2014), suggesting that cannabis use might negatively impact the development and course of mood disorders. Moreover, through processes such as negative reinforcement learning and the related neuroadaptations (Koob and Volkow 2010), cannabis use can trigger the development of a cannabis use disorder (CUD) (Lazareck et al. 2012; Bonn-Miller et al. 2014).

Cannabis is comprised of over 400 compounds, including more than a hundred cannabinoids, which interact with the endocannabinoid system of the body (Ferland and Hurd 2020). The endocannabinoid system is composed of neurotransmitters, such as anandamide, that bind to cannabinoid receptors (CBRs) throughout the central nervous system (CNS; Ferland and Hurd 2020). Cannabinoid-1 (CB1) receptors are especially densely distributed throughout the brain, including regions such as the striatum, ventral tegmental area (VTA), amygdala and hippocampus (Mackie 2005), and are involved in a multitude of cognitive processes, including reward evaluation, salience attribution, learning and memory (Mechoulam and Parker 2013). Importantly, neurobiological models of both mood disorders and CUD stress the importance of these systems in the development and maintenance of the disorders (Malhi et al. 2015; Ferland and Hurd 2020). The most abundant cannabinoids in cannabis are Δ−9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC is the main driver of the psychoactive effect of cannabis, primarily through binding to the CB1 receptor (Ferland and Hurd 2020). Through activation of CB1 receptors, THC can also induce dopamine release in the VTA and striatum affecting the dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways of the brain (Bossong et al. 2009). While CBD has very low binding affinity with CB1 and CB2 receptors, it may antagonize part of THC’s effects (Ferland and Hurd 2020). CBD is also an antagonist of 5-HT1A serotonin receptor (Russo et al. 2005), which has been implicated in mood disorders (Kishi et al. 2013).

As concluded by previous reviews (Mammen et al. 2018; Lucatch et al. 2018; Lowe et al. 2019; Botsford et al. 2020), the high comorbidity between CUD and mood disorders, and their overlapping neurobiological mechanisms highlight the link between cannabis use, CUD, and mood disorders, but the exact nature of the relationship remains unclear. Cannabis use or CUD may increase the risk of developing a mood disorder or vice versa, or shared underlying mechanisms and risk factors may explain the high rates of comorbidity. Integrating the evidence for both cannabis use and CUD, the goal of this narrative review is to evaluate longitudinal, genetic and neurocognitive evidence for the association between cannabis use, CUD and mood disorders. Potential moderators will be discussed, as well as the impact of comorbid cannabis use and CUD on prognosis and treatment of mood disorders. Evidence for depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, as well as suicide will be reviewed separately.

Cannabis and Depression

Clinical characteristics

Depressive disorders are amongst the most prevalent types of mental illnesses, with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Dysthymia (sometimes referred to as persistent depressive disorder) being the most common sub-types. Both are characterized by negative mood states, lack of energy, sadness, sleep disturbances, and general lack of enjoyment in life, with MDD encompassing both single or recurring episodes, and dysthymia referring to a less severe but chronic presentation of symptoms (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013). Much of the research on cannabis use and depressive disorders focuses on MDD, dysthymia, or depressive symptoms. We will use the term depression when discussing the evidence, except for when clear differences exist between disorders.

Comorbidity in heavy and dependent cannabis users: prevalence and moderators

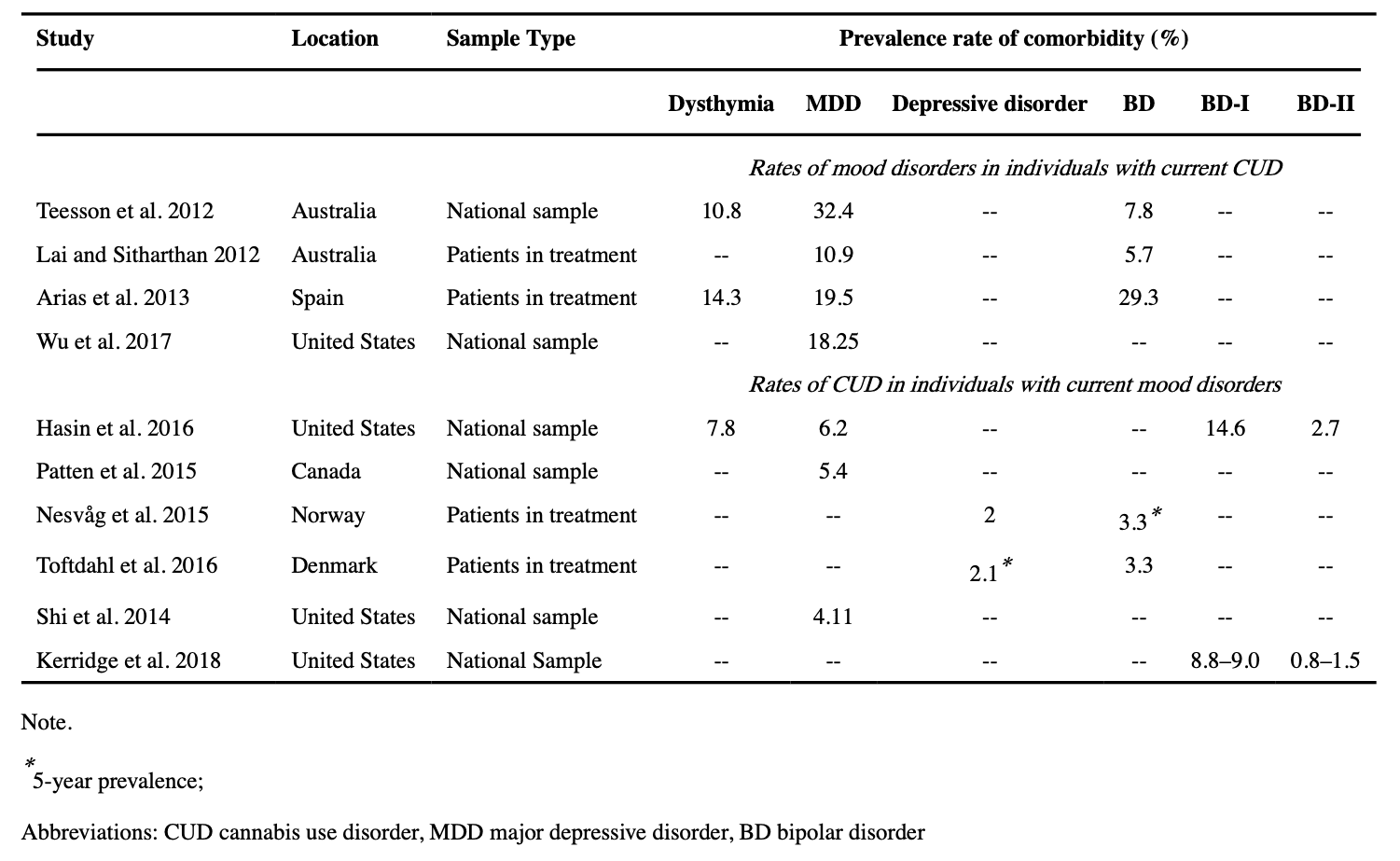

Depression diagnoses, particularly MDD, are very prevalent in individuals diagnosed with CUD (see Table 1 for overview), with rates ranging from 18.25–32.4% for MDD and 10.8% for dysthymia across multiple epidemiological studies (Lai and Sitharthan 2012; Teesson et al. 2012; Arias et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2017). When looking at individuals receiving treatment for CUD, prevalence rates are similar ranging from 10.9%−19.5% (Australia & Spain) for comorbid MDD and 14.3% for comorbid dysthymia (Spain; Lai and Sitharthan 2012; Arias et al. 2013). While depression diagnoses are more prevalent in individuals with any SUDs compared to individuals without a SUD, individuals with CUD are particularly likely to have comorbid depression (Arendt et al. 2007). The prevalence of CUD diagnosis for individuals with depression is considerably lower, ranging from 5.4–6.2% for MDD and 7.8% for dysthymia (Patten et al. 2015; Hasin et al. 2016). For comparison, the past year prevalence of CUD in the general population are estimated at 1.1– 2.5% (Patten et al. 2015; Hasin et al. 2016). In patients in treatment for depression, approximately 2.0% have comorbid CUD (Nesvåg et al. 2015; Toftdahl et al. 2016).

While a wide range of individual differences may moderate it, the cannabis-depression association appears to persist across development with associations appearing in both adolescents and adults (see meta-analysis of adolescent studies in Gobbi et al. 2019). Fergusson et al. (2002) found that 36% of adolescents from a New Zealand birth cohort who used cannabis ten or more times by age 15–16 met criteria for a mood disorder, compared to 18% of those who used less than ten times, and 11% who had never used. More recently, cannabis use (but not CUD) was associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents aged 16–19 (Leadbeater et al. 2019), while a dose-response relationship has also been observed between cannabis use at baseline and depressive symptoms after two years in high schoolers (Rasic et al. 2013). Adolescent onset of cannabis use may strengthen the association. In a 40-year follow-up study, adolescent-onset cannabis users (before age 18) had an increased risk of developing MDD by the age of 48 (age at final follow-up), but later-onset users (after age 27) did not (Schoeler et al. 2018). However, evidence for this moderation effect is mixed, with some studies failing to find an effect of age of onset after controlling for confounding factors such as other substance use and pre-existing anxiety or depression (systematic review: Hosseini and Oremus 2019).

Women are more likely to report concurrent depression and cannabis use than men. In the US, women with CUD had higher rates of current MDD (35.7%) compared to men (20.3%), while rates of comorbid dysthymia were similar in men (9.2%) compared to women (10.2%; Kerridge et al. 2018). This may particularly be the case for emerging adults; women compared to men demonstrated stronger associations between both cannabis use and CUD with depression between the ages of 18–26, but not below the age of 18 and above the age of 26. (Leadbeater et al. 2019). The differences in the sex distribution of samples may contribute to inconsistent findings across studies given the evidence for sex differences in the relationship between cannabis use, CUD, and depression.

Racial differences in rate of comorbidity have also been observed in the US, with black Americans with past-year CUD showing significantly lower rates of past-year MDD (13.8%) and mixed-race Americans showing significantly higher rates of past-year MDD (29.02%) compared to the average prevalence (18.25%; Wu et al. 2017). The mechanisms behind these racial disparities is unclear, but previous work has shown that black Americans are more likely to be diagnosed with CUD (Richter et al. 2016) as well as cannabis ‘abuse’ in drug treatment facilities when referred through the criminal justice system (McElrath et al. 2016). Inflated rates of CUD in black Americans may deflate rates of comorbidity in this group; however, black Americans are also less likely in general to be diagnosed with mood disorders (Delphin-Rittmon et al. 2015). Whether lower rates of CUD and MDD comorbidity reflects racial differences in the true prevalence of these disorders rather than the result of biased or misdiagnosis is not yet clear. Aside from this, there is limited research into the specific effect of race or other cultural factors and the risk of developing comorbid CUD and depression.

Although many studies use coarse measures of cannabis use (e.g. dichotomous ever-use or past-year use variables), the frequency and severity of cannabis use likely matters. In 2014, a meta-analysis of 14 studies found evidence for a slight increased risk of depression in individuals who had ever used cannabis, and a moderate increased risk for heavy cannabis users, suggesting a dose-response relationship between cannabis and depression outcomes (Lev-Ran et al. 2014). In line with this, using discordant twin models, Agrawal et al. (2017a) only observed a robust association between frequent cannabis use and MDD, but not between lifetime cannabis use and MDD. In addition, the presence of cannabis-related problems seen in individuals with a CUD diagnosis may be more strongly related to depression than the heaviness of cannabis use itself. For instance, frequent Dutch cannabis users with CUD had significantly higher odds (OR: 2.93) of having any mood disorder than frequent users without CUD, despite similar quantity and frequency of cannabis use (Van der Pol et al. 2013). In fact, non-dependent frequent users did not have increased prevalence of MDD or dysthymia compared to the general population (Van der Pol et al. 2013). In an Australian study, cannabis users with past-year CUD had higher rates of MDD (32.4%) than users without a CUD (11.8%; Teesson et al. 2012). Furthermore, Bovasso (2001) found that individuals with CUD at baseline were four times more likely to have depressive symptoms approximately fifteen years later compared to those without CUD. In comparison, Danielsson et al. (2016) found no association between cannabis and depression in a prospective 3-year study when using a dichotomous lifetime ever versus never use variable to capture cannabis exposure.

As self-report measures of cannabis use have their limitations but are clearly crucial to investigate the association with depression, some studies have attempted to use more objective measures of cannabis exposure by quantifying the THC potency of individuals’ cannabis exposure. Using hair analysis to classify users either as ‘high THC’ or ‘low THC’ exposed, Morgan et al. (2012) found that those with high levels of THC in their hair reported higher depression scores than the low THC group. In contrast, there was no evidence of an association between depression and self-reported use of high potency cannabis in a cohort study of past-year cannabis users (Hines et al. 2020).

While it is clear that individuals with a CUD are more likely to also be diagnosed with a depressive disorder, there are important moderators of this association that need to be further investigated. While the association seems stable over countries and ages, there is evidence that earlier onset of use, being a woman, higher CUD symptom severity, and higher THC levels might increase the risk of comorbidity.

Potential underlying mechanisms

Although the high rates of comorbidity and the first longitudinal studies suggest a bidirectional association between cannabis use, CUD and depression, the causality and underlying mechanisms of the association are unclear. Moreover, while the early longitudinal evidence pointed towards a dose-response relationship in the effect of cannabis on depressive outcomes (meta-analysis: (Lev-Ran et al. 2014), multiple more recent population-based studies have found no evidence for a causal pathway from cannabis use to depression (Feingold et al. 2015; Blanco et al. 2016; Danielsson et al. 2016). To further elucidate the direction of the association and possible mechanisms involved therein, we will discuss findings from genetic studies, evidence for the shared neurocognitive mechanisms between CUD and depression, and self-medication in more detail below.

Shared genetic vulnerability and gene-environment interactions

Cannabis use, CUD, and depression are all heritable traits, with 40–48%, 51–59%, and 31–42% estimated heritability respectively (Sullivan et al. 2000; Pasman et al. 2018), and there is significant genetic correlation between cannabis use and depression indicative of shared genetic etiology (Hodgson et al. 2017, 2020). A cross-sectional twin study suggested that shared or correlated genetic vulnerabilities contribute to the comorbidity of CUD and MDD (Lynskey et al. 2004). Recently, these findings were partially confirmed by a large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analysis for CUD that found evidence for overlap in genetic liability between CUD and MDD (genetic correlation, rg = .32; Johnson et al. 2020). For comparison, while significant, the genetic overlap between MDD and CUD is lower than between depression and anxiety which is estimated at between .74–1.00 (Roy et al. 1995; Kendler et al. 2007). To determine the direction of the association, Smolkina et al. (2017) applied a model-fitting approach in which various models which differed in the underlying assumptions about the causal pathways between CUD and MDD (i.e. unidirectional causation, reciprocal causation, three independent disorders, etc.) were fit to the twin data. The models in which CUD preceded MDD fit the data better than models with the reverse temporal order. The best fitting models both suggest that genetic and non-shared environmental factors play a role in the development of comorbidity.

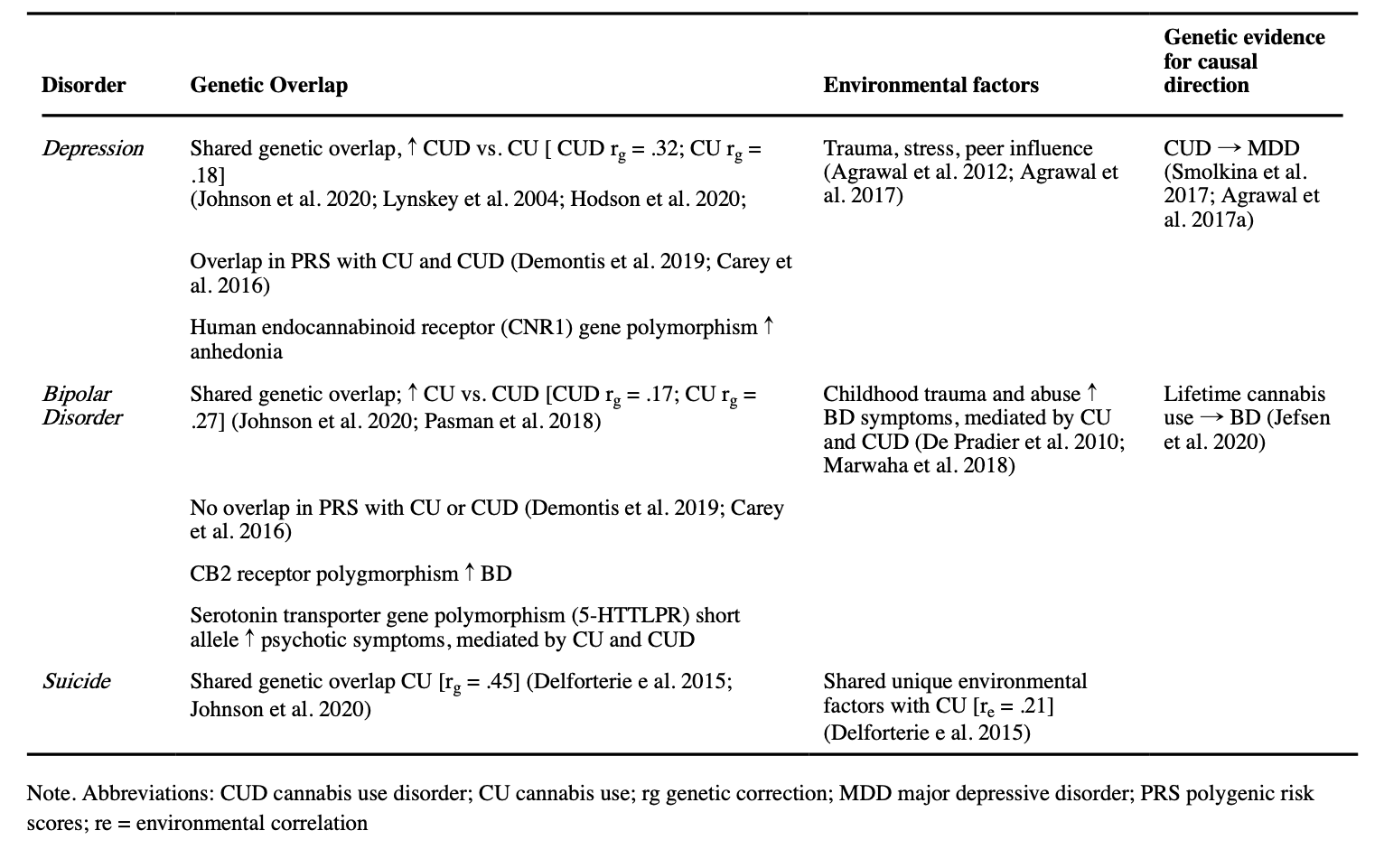

Shared genetic vulnerability may play a larger role in the association between depression and CUD than the association between depression and non-CUD measures of cannabis use. In the recent GWAS for CUD, while shared liability was still present, it was significantly smaller between cannabis use and MDD(rg = .18) than between CUD and MDD (rg = .32; Johnson et al. 2020). Furthermore, in a retrospective twin study, monozygotic frequent user twins were more likely to have MDD than their non-using twin pair (Agrawal et al. 2017a). These results are suggestive of a role for cannabis use itself in the link with depression, but there was also evidence that unique environmental factors could be contributing to the cannabis-MDD associations observed in cannabis use discordant monozygotic pairs (e.g. trauma, stress, or peer influence). For example, in individuals with a specific polymorphism of the human endocannabinoid receptor (CNR1) gene, childhood abuse seems to be more strongly related to development of anhedonia and related depressive symptoms (Agrawal et al. 2012). Furthermore, Hodgson et al. (2020) investigated the phenotypic and genetic relationship between cannabis use, depression, and self-harm using GWAS, genetic correlations, polygenic risk scoring, and mendelian randomization. Cannabis use was more strongly related to self-harm than depression on both a phenotypical and genetic level. Although the genetic results converged to indicate shared genetic influences on cannabis use, depression, and self-harm, the sample was underpowered to detect the causal direction of the associations. Other studies using polygenic risk scores have found significant overlap in shared common genetic risk factors between CUD and depression (Demontis et al. 2019) and non-problem cannabis use and MDD (Carey et al. 2016). Importantly, shared genetic associations generally only explain small parts of the observed variance, suggesting an important role for environmental factors and gene-environment interactions in the development of comorbidity (see Table 2 for overview).

Overlapping neurocognitive substrates

Altered reward processing has been implicated in both depressive disorders and CUD. While this may result in the reduced ability to experience positive affect (i.e. anhedonia) in depression, it may reflect heightened sensitivity to cannabis-related rewards in combination with reduced sensitivity to other rewards in the environment in CUD (Zhang et al. 2013; Ferland and Hurd 2020). Separate studies of individuals with depression and cannabis use have shown attenuated reward anticipation in striatal regions (part of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway; van Hell et al. 2010; Pizzagalli 2014; Martz et al. 2016). Interestingly, reward-related striatal activity appears to be further attenuated in depressed individuals who use cannabis compared to those who do not, suggestive of an exacerbating effect of cannabis on reward dysregulation in depression (Spechler et al. 2020). This is particularly important given evidence that lower striatal functioning is related to poor treatment outcomes in both depression and CUD (Kober et al. 2014; Greenberg et al. 2020).

Additionally, dysfunctional affective regulation plays a role in both depression and CUD (Joormann and Stanton 2016; Ferland and Hurd 2020). While more research is needed to clarify the potential role of affective regulation in comorbid CUD and depressive disorders specifically, preliminary evidence suggests a link between depressive symptoms, cannabis use and structure and function of the underlying brain systems. For instance, cannabis users were more likely to exhibit a morphological variation in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) associated with poor regulatory control than non-cannabis users; however, this variation was only associated with depressive symptoms in individuals with higher rates of lifetime cannabis use (Chye et al. 2017). Furthermore, higher levels of depressive symptoms have been associated with greater frontolimbic connectivity in cannabis users (Shollenbarger et al. 2019; Ma et al. 2020).

The endocannabinoid system is also thought to be directly involved in emotion processing and stress reactivity, which are central to the development of depression and CUD. Although studies are still limited, THC intoxication may negatively affect emotion recognition for faces with negative emotional content only (Bossong et al. 2013). Moreover, augmented endocannabinoid signaling is associated with susceptibility to stress, while suppressed signaling in the amygdala is suggested to play a role in resilience to traumatic stress (Bluett et al. 2017). Hypersensitivity of the amygdala during threat and affective appraisal has been implicated in depression, with MDD related to increased activity of the amygdala (e.g. Mingtian et al. 2012). The amygdala has a high density of CB1 receptors and undergoes important developmental changes during adolescence (e.g. myelination, synaptic pruning; Bossong and Niesink 2010). The use of cannabis during this time may disrupt these developmental processes, providing a possible explanation for the association between early onset of cannabis use and later development of depression. Although current evidence for this causal pathway is limited, cannabis use during adolescence is related to heightened reactivity of the amygdala in response to negative emotions, paralleling findings from studies in depressed individuals (Spechler et al. 2015). Interestingly, research on the effects of acute intoxication in adulthood show that cannabis reduces amygdala response to negative faces (Phan et al. 2008; Gruber et al. 2009), potentially reflecting an anxiolytic effect that can reduce depressive symptoms.

Taken together, cannabis use during critical developmental periods may have downstream effects on affect and threat appraisal that could partly explain the increased vulnerability of early-onset users to depression, but the anxiolytic effects of cannabis intoxication in adulthood may also point towards a path from depression to cannabis use through self-medication.

Self-medication

Self-medication of depressive symptoms is a possible explanation of the pathway from depression to cannabis. In a recent prospective longitudinal study, Feingold et al. (2015) found no association between past-year cannabis use and the development of MDD. However, when looking at never-users of cannabis only, those with past-year MDD were significantly more likely than those without to initiate cannabis use. A similar pattern was observed in adolescents, with depression at age 15 predicting subsequent weekly cannabis use after adjusting for other substance use (Bolanis et al. 2020). A recent meta-analysis of self-reported reasons for medical cannabis use further showed that 34% reported depression as a reason for using cannabis (Kosiba et al. 2019). Individuals with clinical or subthreshold depression may find acute relief of symptoms as cannabis intoxication can induce positive effects on mood (e.g. euphoria) and relaxation (Green et al. 2003). A systematic review of the use of cannabis in populations with serious medical conditions (e.g. HIV, multiple sclerosis) also suggests that cannabis has positive effects on mood. Improvement in mood in this population may be partially due to the alleviation of disease symptoms as opposed to direct effects of cannabis on mood itself (Walsh et al. 2017). At the same time, depressive symptoms in medical users are positively associated with cannabis use problems (e.g. Bonn-Miller et al. 2014)). Although people may be using cannabis as a way to cope with or reduce their depressive symptoms, it may in turn lead to harmful patterns of cannabis use. This is a particularly relevant issue given that individuals with depression report lower levels of perceived risk of cannabis use and have shown a more rapid increase in daily use than individuals without depression (Pacek et al. 2020).

Prognosis and treatment

Comorbidity might also have an effect on treatment-seeking behavior. For example, Wu et al. (2017)found that individuals with CUD who had a comorbid MDD diagnosis were more likely to seek cannabis-related treatment than individuals with CUD alone. Nevertheless, there are reasons to believe that patients with comorbid CUD and depression have a worse prognosis compared with patients with CUD or depression only. In a two-year prospective longitudinal study in individuals with CUD, more cannabis use at baseline was associated with a larger number of depressive symptoms at follow-up (Feingold et al. 2017). Most available treatment options focus on one specific disorder and healthcare systems are rarely equipped to effectively deal with the presence of comorbid disorders. However, patients with comorbid MDD and CUD may present with more severe negative symptoms of depression (e.g. blunted affect, emotional and social withdrawal, difficulty in abstract thinking, etc.) than MDD patients who do not use cannabis (Bersani et al. 2016). Moreover, although research in this area is still limited, cannabis use might exacerbate the neural changes associated with depression (Radoman et al. 2019; Spechler et al. 2020).

Diverging psychopathological profiles and the potentially worse prognosis in comorbid patients may warrant tailored depression treatment in these individuals. Pharmacological treatments for comorbid patients have shown little efficacy (Cornelius et al. 2010; Levin et al. 2013). However, a combination of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to reduce both cannabis use and depressive symptoms for individuals with MDD and problematic cannabis use (Kay-Lambkin et al. 2009). Furthermore, it is unclear whether combined treatment of both disorders is more effective or whether treating one disorder can also lead to a reduction of symptoms of the other disorder. For example, a reduction of cannabis use and abstinence can also lead to reductions in depressive symptoms (Moitra et al. 2016; Lucatch et al. 2020). Lucatch et al. (2020) showed that in individuals with comorbid CUD and MDD, 28 days of cannabis abstinence led to a 43.7% reduction in depressive symptoms, especially anhedonia (88.7% reduction from baseline). However, a reduction of cannabis use does not appear to be necessary to see improvements in depressive symptoms in individuals with CUD (Arias et al. 2020). It is possible that the therapeutic support provided in cannabis use reduction interventions may have an independent effect on depression symptoms. Future studies should consider the use of a control condition which offers similar levels of therapeutic support that is not specific to cannabis reduction in order to determine the specificity of the effect of cannabis cessation on depressive symptoms.

As discussed above, cannabis intoxication may offer temporary relief from depression symptoms, but the evidence of an exacerbating effect of cannabis use on symptoms does not support cannabis use as a long-term solution to cope with depression. However, there is growing interest in the therapeutic effects of CBD specifically. Based on animal models showing a quick and sustained dose-dependent effect of CBD on depressive behavior (Silote et al. 2019), clinical studies have begun to explore the anti-depressant effect of CBD administration. Evidence for a beneficial effect in humans is very limited so far. In one study in patients being treated for chronic cannabis use, 200mg of CBD led to improvements in depression severity (Solowij et al. 2018).

Cannabis and Bipolar

Clinical Characteristics

Bipolar disorder (BD) can be divided into multiple subtypes, all characterized by fluctuations in mood and energy that impede the ability to function in everyday life (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013). More specifically, individuals with bipolar disorder I (BD-I) experience at least one episode of mania, with or without periods of hypomania and major depressive episodes. Mania is characterized by extremely high energy levels, excitement, and euphoria which can lead to destructive behavior and can persist for longer periods of time, while hypomania is a less severe presentation of the same symptoms that only last for several days. Individuals with bipolar disorder II (BD-II) experience at least one major depressive episode and one hypomanic episode, but without the presence of manic episodes. A cyclothymia diagnosis is given when someone experiences persistent alternations of subclinical periods of depression and mania that do not meet the diagnostic criteria of BD-I or BD-II. Psychotic symptoms including delusions, disordered thought, catatonia, and hallucinations may also be present in both depressive and manic states, with lifetime prevalence estimates between 50–90% in individuals with BD (Dunayevich and Keck 2000). We will use the term bipolar disorder (BD) except when findings distinguish between BD-I, BD-II, and cyclothymia.

Comorbidity in heavy and dependent users: prevalence and moderators

About 30% of all individuals with BD are estimated to use cannabis (Pinto et al. 2019). Comorbidity of CUD and BD is more prevalent than comorbidity of CUD and depression in both community-based and clinical populations (see Table 1 for overview). A meta-analyses of community and clinical samples from 1990–2015 revealed an approximately 20% prevalence of current CUD in individuals with BD (Hunt et al. 2016a, b). When looking at subtypes of BD, CUD comorbidity is higher for BD-I (14.6%) than BD-II (2.7%; Hasin et al. 2016). Of individuals with BD who have received or are currently receiving psychiatric treatment, CUD comorbidity is estimated at approximately 3.3% (Nesvåg et al. 2015; Toftdahl et al. 2016). Of note, the diagnostic exclusion criteria for BD-II as well as sex differences in BD-I and BD-II diagnostic rates may help explain the substantial difference in comorbidity of these disorders with CUD. The BD-II diagnostic criteria specifically excludes individ for substance or medication use that may contribute to symptomology (Angst 2013). Cannabis use may be considered to meet this criterion for some clinicians, potentially deflating rates of CUD and BD-II comorbidity. Furthermore, while BD-I is equally prevalent in men and women, BD-II is significantly more prevalent in women (Arnold 2003). Because CUD is more prevalent in men (Hasin et al. 2016), this may contribute to lower comorbidity rates for BD-II.

Among individuals diagnosed with CUD, BD comorbidity is lower but still substantial. A meta-analysis showed an approximately 10% prevalence rate of BD in individuals with CUD in both community and clinical samples (Hunt et al. 2016a, b). BD-I (8.8–9.0%) is more prevalent than BD-II (0.8–1.5%) in individuals with CUD (Kerridge et al. 2018). Although less common than in CUD, BD is also more common in cannabis users without CUD compared to the general population (2.5%; Teesson et al. 2012).

Moreover, sex may moderate the association between cannabis use and BD. While men and women with CUD have similar rates of BD (Kerridge et al. 2018), a recent meta-analysis found more frequent cannabis use in those individuals with BD who were younger, male, lower educated, single, and those with higher lifetime use of other substances (Pinto et al. 2019). Cannabis use also appears to be associated with specific BD outcomes including earlier onset of the disorder, lifetime presence of psychotic symptoms, and suicide attempts (Pinto et al. 2019). Related to this, CUD comorbidity has been associated with the presence of manic/mixed episodes and psychotic features in BD (Weinstock et al. 2016). Individuals diagnosed with both CUD and BD are also more likely to have other comorbid disorders, such as other substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder, compared to individuals with BD only (Lev-Ran et al. 2013; Weinstock et al. 2016).

Potential underlying mechanisms

Compared to depression, much less research has been done to unravel the potential mechanisms underlying the association between cannabis use, CUD and BD. Regarding the direction of the association, most studies point towards a path from cannabis use to the onset of BD and manic symptoms. For instance, in a US study, regular cannabis use (≥ weekly in past year) was a unique predictor of the onset of BD (Cougle et al. 2015), which is in line with previous evidence in a Dutch sample (Van Laar et al. 2007). However, another US study did not observe this association (Feingold et al. 2015). At the level of symptom polarity, a 2015 meta-analysis including two studies found a threefold increase in the risk of manic symptom onset in cannabis users (Henquet et al. 2006; Tijssen et al. 2010; Gibbs et al. 2015). More recently, a UK birth cohort study found a dose-response relationship between cannabis use at age 17 and the presence of hypomania at age 22–23 (Marwaha et al. 2018). While the causal direction is still unclear, heightened manic symptoms in relation to cannabis use may also contribute to the remarkable difference in prevalence rates of comorbid CUD in people with BD-I (8.8–14.6%), which requires full manic episodes for diagnosis, compared to those with BD-II (0.8–2.7%), which only requires the presence of hypomania for diagnosis. Although most research on the link between cannabis and psychotic symptoms is conducted in individuals with other psychotic disorders, a few studies have observed an association between cannabis use and the presence of psychotic symptoms in BD patients specifically (Weinstock et al. 2016; Etain et al. 2017; Pinto et al. 2019). For instance, individuals with comorbid CUD are more likely to present with psychotic features than individuals without CUD (Weinstock et al. 2016) and a meta-analysis showed cannabis users with BD were more likely to report psychotic symptoms (Pinto et al. 2019). Furthermore, using a path analysis approach, Etain et al (2017) found that lifetime prevalence of cannabis abuse or dependence (DSM-IV criteria) was uniquely associated with delusional beliefs in BD patients. Little is known about the association between cannabis use and depressive symptoms in BD specifically. This may be partially explained by the fact that individuals later diagnosed with BD, are often first diagnosed with MDD after the initial depressive episodes (Stiles et al. 2018).

Several studies have examined the effect of cannabis use and CUD on the age of BD onset, with most evidence pointing towards an earlier age of BD onset in cannabis users regardless of the polarity of symptoms (i.e. manic or depressive; De Hert et al. 2011; Lagerberg et al. 2011; Lev-Ran et al. 2013). For instance, Lagerberg et al. (2014) found a dose-response relationship between cannabis use and age of BD onset, irrespective of episode polarity and presence of psychotic features (2014). The average age of BD onset for individuals who used cannabis between 0–10 times was 23.2 years, decreasing to 20.5 years for >10 times per month and 18.6 years for those with lifetime CUD. While these results suggest that cannabis use precedes BD onset, other research is suggestive of a bidirectional relationship in which lifetime cannabis use is associated with an earlier onset of BD regardless of whether cannabis use was initiated before or after the diagnosis (Lagerberg et al. 2011). Importantly, the effect of cannabis on age of BD onset was specific to cannabis, as alcohol use and other substance use were related to later age of BD onset.

Despite most studies looking into trajectories from cannabis use towards BD, there is also some evidence for the opposite pathway from BD and mania to cannabis use. For example, earlier age of BD onset also increased the risk of later cannabis use (Lagerberg et al. 2011). A study investigating the effect of the duration of untreated BD-I found that longer durations of untreated illness increased the risk for initiating cannabis use (Kvitland et al. 2016).

Shared genetic vulnerability and gene-environment interactions

As in depression, part of the association between BD and cannabis use may be explained by shared genetic vulnerability and neurocognitive mechanisms. Heritability estimates of BD are higher than in depression, with estimates ranging from 59–85% (McGuffin et al. 2003; Lichtenstein et al. 2009; Wray and Gottesman 2012). A recent GWAS identified shared genetic factors involved in BD and CUD (rg = .17), as well as for BD and cannabis use itself (genetic correlation = .27; Johnson et al. 2020). For comparison, the genetic correlation between BD and schizophrenia is substantially higher (rg = .60; Lichtenstein et al. 2009). Notably, the genetic overlap between BD and CUD was smaller than observed for MDD and CUD (rg = .17 vs rg = .32). Similarly, a GWAS of lifetime cannabis use, rather than CUD, showed that there were significant genetic correlations (rg = .27) with a diagnosis of BD (Pasman et al. 2018). This highlights the possibility that comorbidity between CUD and BD arises from shared genetic liability for cannabis use rather than CUD specifically. In addition, a recent study using Mendelian Randomization to examine the causal pathways between lifetime use and BD found that genetic liability to BD was causally related to using cannabis at least once, but not the other way around (Jefsen et al. 2020). In contrast, two studies using polygenic risk scores to examine the overlap in common genetic risk factors for CUD and cannabis use with other psychiatric disorders did not find a significant overlap with BD (Carey et al. 2016; Demontis et al. 2019). Importantly, BD-I and BD-II are not considered separately in these genetic studies, which may obscure differences in the overlapping shared genetic vulnerability of both disorders with cannabis use and CUD.

Functionality of the endocannabinoid system may partially explain comorbidity as the presence of specific polymorphisms of the gene coding for the CB2 receptor has been found to increase the risk for BD (Minocci et al. 2011). It has also been suggested that during neurodevelopment, a genetic liability for BD interacts with the endocannabinoid system, and when an individual subsequently uses cannabis this pre-existing liability for BD is unmasked (De Hert et al. 2011). Moreover, genetic variations in the gene coding for the serotonin transporter may play a role (De Pradier et al. 2010). Preliminary results showed that individuals with a BD diagnosis who carry the short allele polymorphism of this transporter gene have increased risk for psychotic symptoms and that the strength of this association might be mediated by cannabis use and dependence. Childhood trauma -particularly abuse- may play a role in the association between cannabis use and BD, as this study also found that while childhood sexual abuse did not directly increase the risk for psychotic symptoms in BD patients with the short allele polymorphism, a history of childhood abuse might have an effect on BD symptomology through increasing the risk for cannabis use and dependence. Childhood abuse has been linked to increased risk for both excessive cannabis use (Hayatbakhsh et al. 2009), BD (Etain et al. 2008) and psychosis (Alemany et al. (2014). Moreover, in a UK birth cohort, cannabis was also found to mediate the association between childhood sexual abuse and hypomania (see Table 2 for overview; Marwaha et al. 2018).

Overlapping neurocognitive substrates

Similarly to MDD (Joormann and Stanton 2016) and CUD (Ferland and Hurd 2020), alterations in affective regulation and reward processing are believed to reflect part of the underlying pathophysiology of BD (Miskowiak et al. 2019). A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies found evidence for hyperactivation in limbic structures, including the amygdala and striatum during emotional face perception (Wegbreit et al. 2014)). However, mood state (e.g. depressive, manic, or euthymic state) may be an important moderator of this effect in BD. While increased activity in the putamen (a part of the striatum) was a stable finding across depressive, manic, and euthymic individuals with BD, amygdala hyperactivation was only observed in depressed and euthymic individuals in response to negative stimuli (Hulvershorn et al. 2012). Additionally, recent meta-analyses indicate that BD is associated with alterations in cortical thickness in regions involved in emotional processing, including fronto-limbic regions and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; Ellison-Wright and Bullmore 2010; Bora et al. 2010). Research on the effect of comorbid cannabis and CUD on emotional processing and the underlying neural correlates is largely missing in BD. One study of adolescents with BD with and without comorbid CUD found that amygdala activity was higher in the BD only group during a cannabis cue exposure task (Bitter et al. 2014). Furthermore, amygdala activity in the comorbid group appeared to be more blunted with more cannabis use. Whether cannabis has a similar blunting effect on amygdala activity in emotion processing-related tasks is unknown.

Compromised cognitive functioning has also been indicated as a potential cause or consequence of BD and appears to be more severe than impairments observed in unipolar depression (Borkowska and Rybakowski 2001). Deficits in domains such as memory, attention, and executive function, which are also found in individuals with CUD (Kroon et al. 2021), have been observed in both depressive and manic states (Murphy et al. 2001; Clark et al. 2001; Martínez-Arán et al. 2004), as well as in the euthymic phase of the disorder (Robinson et al. 2006). A recent systematic review of the association between cannabis use and cognitive functioning in BD found mixed evidence (preprint; Walter et al. 2020). Braga et al. (2012) found that individuals diagnosed with BD-I who had a history of CUD performed better on tasks assessing processing speed, working memory and attention than individuals with BD-I only. Similarly, Ringen et al. (2010) observed better cognitive function in cannabis users than non-users with BD. In contrast, two studies found no association between cannabis use and cognitive function (Sagar et al. 2016; Abush et al. 2018), and one observed worse performance in symptomatic BD patients with comorbid CUD (Halder et al. 2016).

Interestingly, adolescents with comorbid BD and CUD showed pervasive differences in brain structure in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions compared to adolescents with BD only (Jarvis et al. 2008; Sultan et al. 2020). Given the relatively brief period of cannabis exposure in adolescents, it is possible that these differences predate cannabis use and may reflect a specific subtype of individual at risk for BD instead of a detrimental effect of cannabis use per se.

Self-medication

Based on current evidence primarily supporting cannabis use preceding BD, self-medication may not be a primary driving force of the association between CUD and BD. Nevertheless, more research is warranted as the relationship between untreated BD-I and initiation of cannabis use (Kvitland et al. 2016) may reflect cannabis use to alleviate BD symptoms. Moreover, individuals with BD frequently report self-medication as their reason for using substances (Weiss et al. 2004; Bolton et al. 2009; Canham et al. 2018) and acute cannabis intoxication in individuals with BD can momentarily alleviate negative affect (Gruber et al. 2012; Sagar et al. 2016). Individuals with BD may also be seeking out the general mood-altering effects of cannabis intoxication, as opposed to symptom relief specifically. For instance, in an experience sampling study of individuals with BD-I or BD-II, higher positive affect increased the likelihood of using cannabis while negative affect and depressive and manic symptoms did not. Cannabis use subsequently further increased positive affect (Tyler et al. 2015).

Prognosis and treatment

Similarly to depression, cannabis use and CUD are related to a more severe course of illness in BD and worse prognosis in treatment-seeking BD patients. Individuals with comorbid CUD and BD show higher BD symptom severity, including more manic, hypomanic, depressive episodes (Lev-Ran et al. 2013), more rapid cycling between affective episodes (Strakowski et al. 2007) as well as more psychotic episodes and hospitalizations than those without CUD (Lagerberg et al. 2016). Cannabis use in general is also related to higher symptom severity, particularly in the domains of mania and psychotic features (Van Rossum et al. 2009). Moreover, continued cannabis use in patients being treated for BD is associated with lower remission rates (Zorrilla et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2015) and poorer global functioning one year after treatment (Kvitland et al. 2015). It is important to note that in these prospective observational studies, it is possible that individuals who were able to reduce cannabis use had higher levels of social or therapeutic support, potentially leading to downstream improvements in BD symptomology that are not directly attributable to cannabis use reduction. In one study, patients with comorbid CUD in treatment for acute mania exhibited delays in the resolution of manic and psychotic symptoms and also needed higher doses of medication to control symptoms compared to those without CUD (Chaudhury et al. 2014). In contrast, patients who quit using cannabis during treatment had similar outcomes to patients who had never used (Zorrilla et al. 2015). Women may specifically experience worse clinical outcomes, such as general mental health problems when using cannabis (de la Fuente-Tomás et al. 2020). As this study only looked at differences between lifetime cannabis users and never-users, research with more sensitive measures of cannabis use and CUD is needed to examine gender-related differences in clinical outcomes.

Despite the evidence indicating that cannabis use and CUD are related to altered clinical course and treatment responsiveness, no studies have been conducted to examine effects on treatment-seeking or specific treatment strategies for comorbid BD and CUD. The distinct cognitive profiles associated with BD with and without CUD, and perhaps even better executive functions in comorbid BD and CUD (Ringen et al. 2010; Braga et al. 2012), but worse prognosis, stress the importance of exploring the benefits of differential treatment strategies. Until then, close clinical monitoring and detailed assessment of cannabis use in patients is indicated.

Cannabinoids have been proposed as a potential therapeutic target for BD based on patients reporting cannabis self-medication and the overlap between neuropharmacological properties of cannabinoids and current pharmacological treatments for BD (Ashton et al. 2005). A systematic review of the use of CBD in psychiatric disorders was unable to identify any clinical trials of CBD in BD patients (Bonaccorso et al. 2019). One study administered CBD to two in-patients with BD-I who were experiencing manic episodes but failed to find any symptom improvement regardless of the dosage (Zuardi et al. 2010). Accumulating evidence suggests CBD may have a beneficial effect on individuals with psychosis (Bonaccorso et al. 2019), but research is needed on individuals with psychotic features in BD specifically before CBD is indicated as a potential therapy.

Cannabis and Suicide

An estimated 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year (WHO, 2019), half of which are diagnosed with either depression or BD (Arsenault-Lapierre et al. 2004). Suicidal ideation and attempts are strong predictors of subsequent risk of suicide in mood disorders (Nordström et al. 1995). We will discuss the link between cannabis use and suicide before examining the limited evidence for the more complex association between cannabis use, mood disorders, and suicide.

Evidence for the link between cannabis and suicide regardless of psychiatric diagnoses is conflicting. A recent meta-analyses found that cannabis intoxication was not linked to increased risk of suicide attempt or death, with limited evidence to suggest that it may actually decrease the risk of suicide attempts (Borges et al. 2016). However, heavy cannabis users were found to be at increased risk of suicidal ideation and attempts in adulthood (Borges et al. 2016). Adolescent cannabis users also appear to be at higher risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, even when adjusting for sociodemographic and drug use variables (Borges et al. 2017; Carvalho et al. 2019). Yet, in men aged 18–20 at baseline, a 30-year follow-up study found no association between occasional or heavy cannabis use and risk of suicide after extensive adjustment of 31 potentially confounding variables (Price et al. 2009). With regards to CUD, evidence suggests that women, late adolescents and young adults with CUD are at elevated risk of suicide compared to men and older adults respectively (Foster et al. 2016). Similarly, a recent meta-analysis found that adolescent cannabis use was associated with a two-fold increase in risk of suicide attempts in adolescence and young adulthood (Gobbi et al. 2019).

Potential underlying mechanisms

Research on the causal pathways between cannabis use and suicidality is limited but suggests a bi-directional relationship. Bolanis et al. (2020) found that cannabis use was associated with greater odds of suicidal ideation after two years, but that suicidal ideation did not predict future cannabis use. Importantly, this association was no longer significant after controlling for other substance use. Also, Mars et al. (2019) showed that cannabis use in adolescence was associated with the transition from suicidal thoughts to attempts. In the opposite direction, Agrawal et al. (2017b) found evidence that suicide attempts may increase the risk of developing CUD in adults, but no evidence that cannabis use or CUD increased the risk of suicidal behaviors. In contrast, a Mendelian randomization study by Orri et al. (2020) observed a causal role for cannabis on suicide attempts, but no evidence of the reverse causal pathway.

Studies investigating the association between cannabis use, depression, and suicide show mixed results. Adult cannabis use was found to increase the chance of developing both depression and suicidal ideation and attempts, but results in adolescents are mixed (Pedersen 2008; Rasic et al. 2013; Halladay et al. 2020). These studies did not examine whether this link between cannabis use and suicidal behavior was moderated by depressive symptoms. More recently, Chabrol et al. (2020) found a dose-response relationship between severity of CUD symptoms and suicidal ideation, which was no longer significant after controlling for depressive symptoms. This suggests that cannabis use may increase the risk of suicidal behaviors through its association with depression.

It is clear that there is an association between cannabis use, BD and suicide, but there is little evidence regarding the direction of the association. Cannabis use is associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts (Pinto et al. 2019)) and a similar relationship was observed with CUD (Bartoli et al. 2019). Furthermore, individuals with a comorbid diagnosis of CUD and BD were found to have a significantly increased risk of attempting suicide than their non-comorbid counterparts (Agrawal et al. 2011) an association also observed for suicidal mortality (Østergaard et al. 2017). Individuals with more severe BD symptoms may be more likely to experience suicidality and also be more likely to use cannabis to cope. However, cannabis may also exacerbate symptoms leading to increased suicidality. The lack of understanding of the causal pathways of this specific association highlights the need for longitudinal studies.

Shared genetic vulnerability and gene-environment interactions

Both cannabis use and suicidal ideation are heritable traits, with heritability estimates ranging from 40–60% (Delforterie et al. 2015). Examining the association between the polygenic risk factors for CUD and suicidal ideation and attempts, Johnson et al. (2020) found evidence for overlapping genetic risk factors using polygenic risk scoring. However, based on twin-modelling, unique environmental influences also contribute to this association (Lynskey et al. 2004). In the only study to date to investigate the extent to which the two phenotypes share a genetic and environmental association, Delforterie et al. (2015) found a genetic correlation of .45 between suicidal ideation and cannabis use, which is substantially higher than the genetic correlations that have been found between cannabis use and BD and MDD. Individual-specific environmental factors are also shared across cannabis use and suicidal ideation, with a correlation of .21 (See Table 2 for overview),

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

The current review provides an elaborate overview of the evidence of the association between cannabis use, CUD, depression, BD and suicide. Despite increasing rates of cannabis use in individuals with mood disorders and the high rates of comorbidity between cannabis use, CUD, and mood disorders, the evidence for the causal directions of these associations and the potential underlying mechanisms is still limited. This knowledge gap is concerning as media and advertising increasingly perpetuate the positive benefits of cannabis use (Park and Holody 2018), especially as treatment for depressive symptoms (Bierut et al. 2017), which are common across mood disorders.

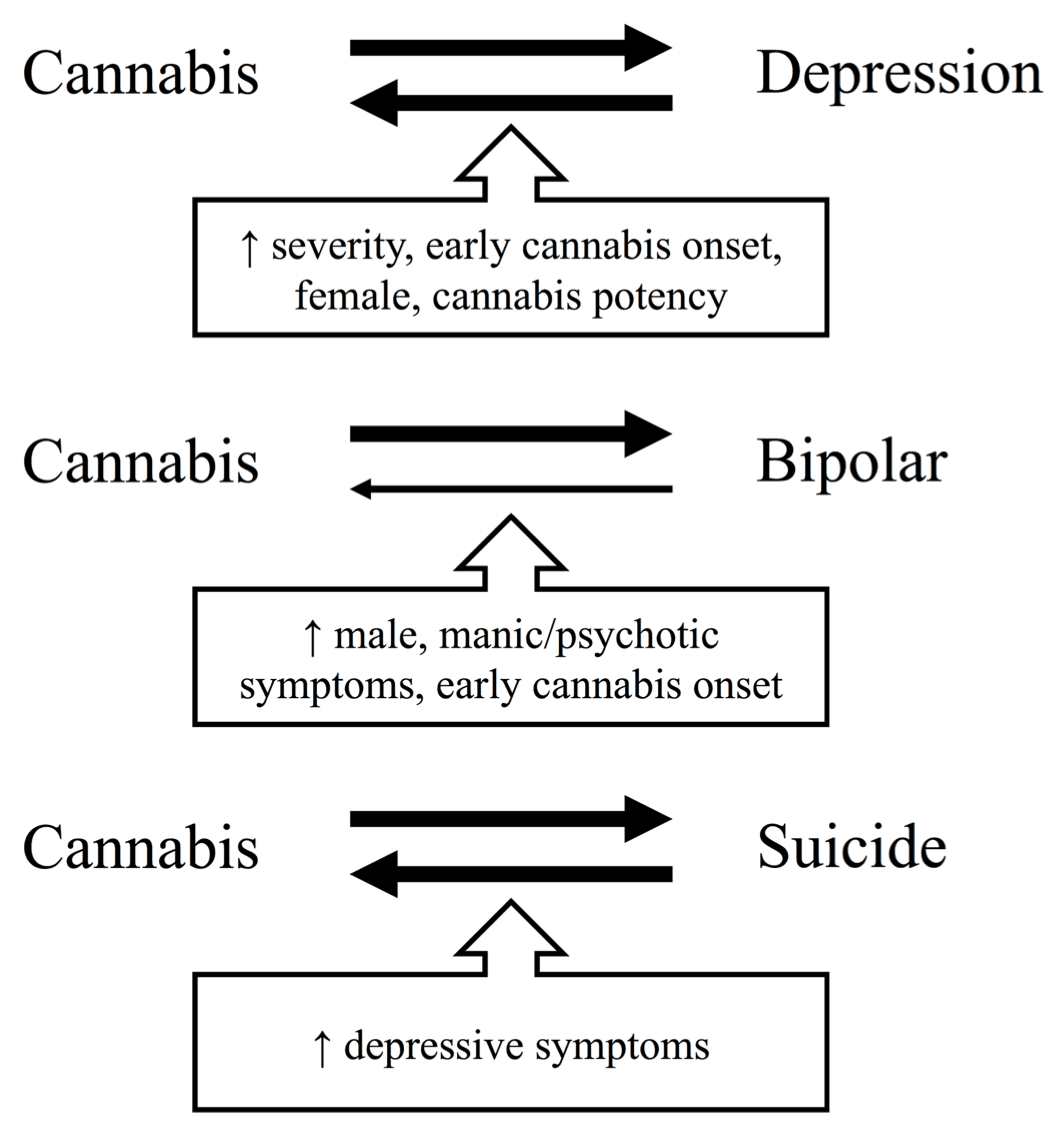

In summary, cannabis use, particularly heavy and dependent use, is likely bidirectionally associated with the onset and course of depression, with evidence that some depressed individuals may initiate cannabis to self-medicate while cannabis use may precede depression in others. This association might be moderated by earlier onset of cannabis use, being a woman, higher CUD symptom severity, and the use of higher potency cannabis (Figure 1). While an overlap in genetic risk factors for cannabis use, CUD, and depression has been observed, the evidence suggests that gene-environment interactions, individual and shared environmental factors, shared neurocognitive substrates, and the effects of cannabis itself play an important role in the development of comorbidity.

Evidence regarding the direction of the association between cannabis use, CUD, and BD is more limited but consistent. While some individuals with BD may initiate cannabis after symptom onset to regulate mood, most studies point to cannabis preceding the onset of BD and increasing the severity of depressive, manic, and psychotic symptoms in BD (Figure 1). The cumulative genetic evidence suggests that comorbidity between CUD and BD may partly arise from shared genetic liability, but that gene-environment interactions play an important role. Particularly, alterations in genes that affect the endocannabinoid, dopaminergic, and serotonergic systems of the brain seem to interact with cannabis use to increase the risk of developing BD.

Regarding suicide, there is a bidirectional association between cannabis use and suicide in the general population, with cannabis use increasing the risk for suicidal behavior and vice versa. Limited evidence suggests this association may be moderated by depressive symptoms (Figure 1). However, little is known about the role of cannabis use in the risk of suicidal behavior in depressed individuals specifically. Converging evidence suggests that cannabis use and CUD are related to heightened risk of suicide in individuals with BD, with an important role for gene-environment interactions in this association.

In agreement with previous reviews (Mammen et al. 2018; Lowe et al. 2019; Botsford et al. 2020), evidence appears stronger for a negative impact of cannabis on BD onset and prognosis than for depression. Nevertheless, despite the more mixed findings of cannabis use leading to depression, there is important evidence that cannabis is harmfully associated with symptom severity and that reductions in use are related to better treatment outcomes (Feingold et al. 2017; Lucatch et al. 2020). We believe the risks currently outweigh the evidence of temporary symptom relief by cannabis intoxication (Li et al. 2020). This is further corroborated by the potential association between cannabis and suicide in individuals with depression (Chabrol et al. 2020) or BD (Pinto et al. 2019; Bartoli et al. 2019).

The nature of the association between cannabis use and mood disorders is complex. Although challenging, prospective longitudinal designs that follow individuals from before the onset of both cannabis and mood disorders can help elucidate the direction of the associations between cannabis use, CUD, and mood disorders. Our understanding of the exact nature of the relationship is further limited by a lack of control over potential confounders, particularly other substance use and mental health problems which are common in individuals with mood disorders (Lai et al. 2015) and CUD (Gorelick 2019). In general, the impact of cannabis use on mental health varies greatly from person to person, but effects appear worse for younger users and effects of sex should be considered (Kroon et al. 2020). Notably, sex-specific effects are evident in CUD, BD, and depression, as well as associations with trauma exposure in each disorder. Differential exposure to trauma or coping mechanisms after trauma may partially account for sex-specific effects in the prevalence and etiology of cannabis and mood disorder comorbidity. For example, while approximately two-thirds of both men and women with depression reported childhood trauma exposure in a recent study, severely traumatized young women with depression were at particular risk of drug misuse (Curran et al. 2021). More research on the role of differential exposure to trauma, as well as access to treatment after trauma in individuals with comorbid CUD and mood disorders is needed to elucidate the underlying causes of sex-specific effects.

The BD literature suggests that cannabis use is specifically associated with worsening of psychotic, manic and depressive symptoms. Cannabis composition likely matters; high THC:CBD ratio products in particular may increase risk of psychotic and manic symptoms, while we know little on the impact of potency or ratio on depressive symptoms (Sideli et al. 2020). In addition, the lack of objective assessments of cannabis use limits our ability to assess dose-response relationships between cannabis use and mood disorder symptoms and trajectories. Researchers should be encouraged to include more objective methods such as hair analysis of cannabis metabolites to examine the influence of different cannabinoids on mood disorders.

Fundamental animal research can also help to elucidate the causal role of cannabinoids in the development of mood disorders. In rodents, exposure to chronic THC or WIN55,212–2—a synthetic CB1 receptor agonist—during adolescence leads to depressive-like behavior characterized by immobility during a forced swim test and anhedonia during a sucrose preference test particularly in females (Rubino et al. 2008; Bambico et al. 2010; De Gregorio et al. 2020). Parallel changes in the serotonergic system have been observed after chronic adolescent cannabinoid exposure in rodents (De Gregorio et al. 2020), which have been suggested to underlie the vulnerability to mood disorders after cannabis use. It is important to note that these findings do not directly translate to human cannabis consumption. While rodents generally receive repeated injections with a single cannabinoid, humans generally smoke cannabis. Moreover, cannabis composition is variable, containing hundreds of cannabinoids, including some like CBD that may offset THC’s effects on mood. For example, Shbiro et al. (2019) showed that ingested CBD counteracts immobility and anhedonia in the forced swim and sucrose preference test in depressive-like genetic rat strains. While animal models help to elucidate the direct effect of specific cannabinoids on depression-related behavior and the corresponding neuromechanisms, the extent to which the finding translate to humans is unclear.

The differential prognosis for depression and BD with comorbid CUD, lack of tailored treatment options, and the complex but unclear interaction between cannabis use, neurocognition, and symptom severity in these patients highlight the need for more studies. While overlapping neurobiology is evident, most studies on the neurocognitive mechanisms of cannabis and mood disorders specifically exclude individuals with comorbidity. Given the prevalence of comorbidity, both fundamental and clinical research should move towards including comorbid groups alongside individuals with a single diagnosis to bolster our understanding of the similarities and differences in the mechanisms underlying mood disorders with and without comorbid cannabis use and CUD. Given the shift in public perception of harm and increase in cannabis being advertised for treating psychiatric symptoms, such studies will hopefully also foster important information that can help prevent harm and optimize treatment for vulnerable individuals.