Abstract

Background Evidence suggests that individuals with history of substance use disorder (SUD) are at increased risk of COVID-19, but little is known about relationships between SUDs, overdose and COVID-19 severity and mortality. This study investigated risks of severe COVID-19 among patients with SUDs.

Methods We conducted a retrospective review of data from a hospital system in New York City. Patient records from 1 January to 26 October 2020 were included. We assessed positive COVID-19 tests, hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and death. Descriptive statistics and bivariable analyses compared the prevalence of COVID-19 by baseline characteristics. Logistic regression estimated unadjusted and sex-, age-, race- and comorbidity-adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for associations between SUD history, overdose history and outcomes.

Results Of patients tested for COVID-19 (n = 188 653), 2.7% (n = 5107) had any history of SUD. Associations with hospitalization [AORs (95% confidence interval)] ranged from 1.78 (0.85–3.74) for cocaine use disorder (COUD) to 6.68 (4.33–10.33) for alcohol use disorder. Associations with ICU admission ranged from 0.57 (0.17–1.93) for COUD to 5.00 (3.02–8.30) for overdose. Associations with death ranged from 0.64 (0.14–2.84) for COUD to 3.03 (1.70–5.43) for overdose.

Discussion Patients with histories of SUD and drug overdose may be at elevated risk of adverse COVID-19 outcomes.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic may disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, including people with substance use disorders (SUDs).1,2 Evidence suggests that individuals with SUDs are at increased risk of COVID-19,3 but little is known about relationships between SUDs, overdose and COVID-19 severity and mortality.4 To address this gap, we conducted a retrospective study of patients tested for COVID-19 at a hospital system in New York City (NYC), an early COVID-19 hotspot and jurisdiction with high rates of opioid and other drug overdose (OD).5

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of data from NYU Langone Health (NYULH), an academic medical center comprising four acute care hospitals across greater NYC.

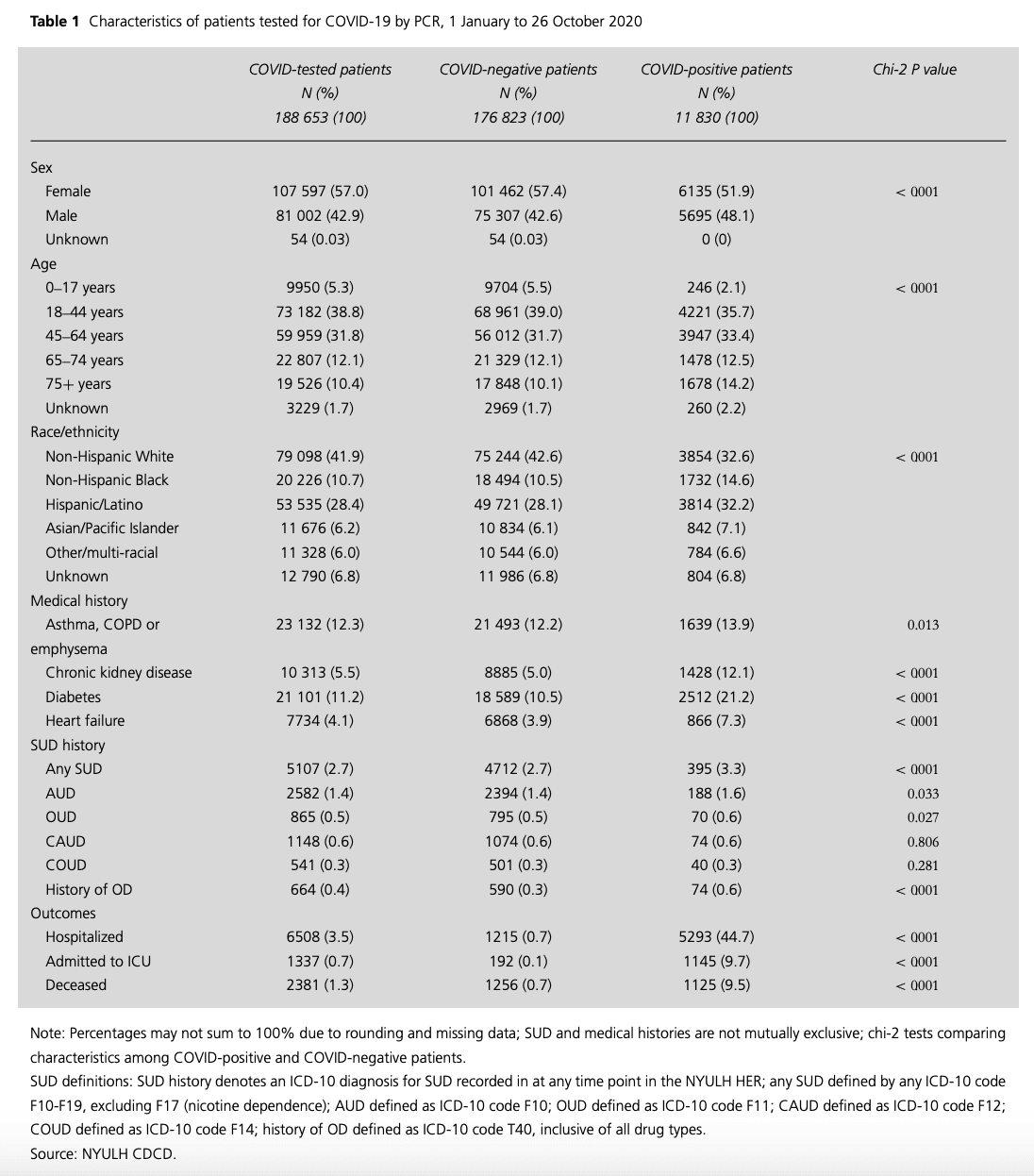

Table 1

Characteristics of patients tested for COVID-19 by PCR, 1 January to 26 October 2020

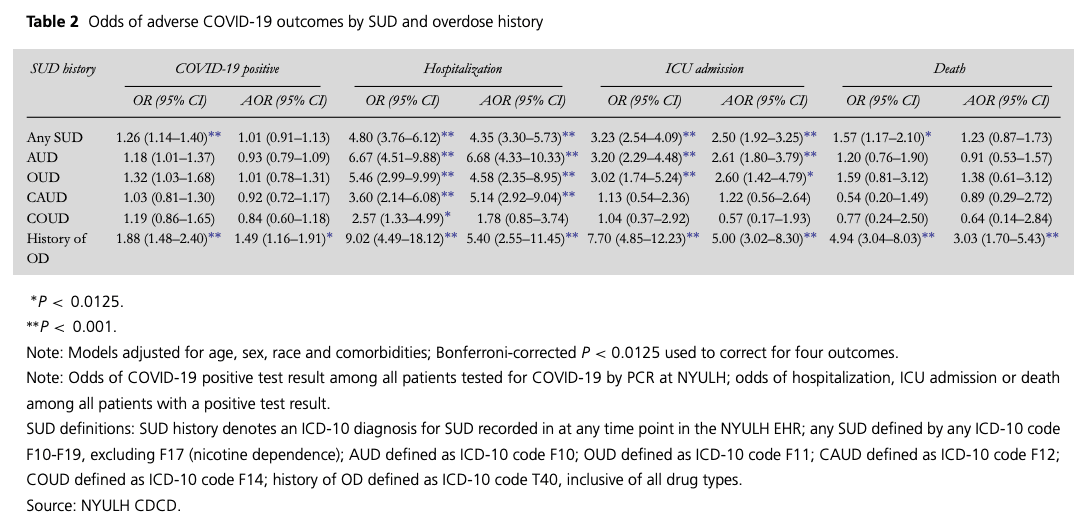

Table 2

Odds of adverse COVID-19 outcomes by SUD and overdose history

We used NYULH’s COVID-19 Deidentified Clinical Database (CDCD), including patients tested for COVID-19 between 1 January and 26 October 2020 (N = 188,653). COVID-19 cases were defined as patients with positive results on reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays of nasopharyngeal swab specimens. Before 16 March 2020, samples were analyzed by the NYC Public Health Laboratory or New York State Wadsworth Laboratory. Beginning 16 March 2020, the NYULH clinical laboratory analyzed samples. Use of the CDCD is exempt under NYULH’s Institutional Review Board.

We assessed four outcomes: positive COVID-19 tests, hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and death. We defined hospitalizations and ICU admissions as admissions for patients with positive tests whose COVID-19 diagnoses were dated concurrently or prior to admission. SUDs and overdose were assessed using ICD-10 codes F10 (alcohol use disorder; AUD), F11 (opioid use disorder; OUD), F12 (cannabis use disorder; CAUD), F14 (cocaine use disorder; COUD), T40 (OD) and F10–F16 and F18–F19 (any SUD). Diabetes, heart failure, chronic kidney disease and asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema were assessed, guided by research on COVID-19 outcomes at NYULH.6 Patient sex, age group, race and living status were obtained from the CDCD.

We calculated descriptive statistics and bivariable analyses to compare the prevalence of COVID-19 by baseline characteristics. We used logistic regression to estimate unadjusted and sex-, age-, race- and comorbidity-adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for associations between SUD indicators and outcomes. A Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.0125 was used for statistical significance (corrected for four outcomes). Analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.2.

Results

Of patients tested for COVID-19 (n = 188 653), 57.0% were female; 22.5% were 65 years or older; 41.9% were non-Hispanic white, 28.4% Hispanic/Latino and 10.7% non-Hispanic Black. Asthma/COPD/emphysema was the most prevalent comorbidity (n = 23 132, 12.3%), followed by diabetes (n = 21 101, 11.2%), chronic kidney disease (n = 10 313, 5.5%) and heart failure (7734, 4.1%). In total, 5107 patients had any SUD (2.7%), with AUD most prevalent (n = 2,582; 1.4%), followed by CAUD (n = 1,148, 0.6%), OUD (n = 865, 0.5%) and COUD (n = 541, 0.3%). Overdose was observed in 664 patients (0.4%). COVID-19 incidence was 6.3% positive (Table 1).

Overdose was associated with COVID-19 [AOR 1.49 (95% confidence interval; CI: 1.16–1.91). Each SUD indicator except COUD was associated with hospitalization; AORs ranged from 4.35 (3.30–5.73) for SUD to 6.68 (4.33–10.33) for AUD. SUD, AUD and OUD were associated with over 2.5 times the odds of ICU admission, and OD with five times the odds [5.00 (3.02–8.30)]. Overdose was associated with mortality [3.03 (1.70–5.43)] (Table 2).

Discussion

This study corroborates prior research and demonstrates that patients with SUDs face disproportionate risk of critical COVID-19 illness.3 Although COVID-19 diagnoses were dated concurrently or prior to admission, we cannot assure whether outcomes were due to COVID-19 or unrelated. Additionally, we adjusted for few comorbidities; due to missing data, body mass index, an important predictor,6 was not assessed. Despite these limitations, this study highlights the need for research identifying risk mechanisms of severe COVID-19 among patients with SUD, such as presentation timing or provider stigma.

Funding

OES and MRK received support from the New York University Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (P30 DA011041). MRK received support from the New York University-City University of New York (NYU-CUNY) Prevention Research Center (U48 DP005008). OES received support from the New York State Department of Health Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program (ECRIP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sponsors, who had no role in study design; data collection, analyses, or interpretation; manuscript preparation; or decision to publish the results.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Bennett Allen, PhD Student

Omar El Shahawy, Assistant Professor

Erin S. Rogers, Assistant Professor

Sarah Hochman, Assistant Professor

Maria R. Khan, Associate Professor

Noa Krawczyk, Assistant Professor