Abstract

Background: Evidence supports integrating drug use treatment, harm reduction, and HIV prevention services to address dual epidemics of drug use disorders and HIV. These dual epidemics have spurred a rise in legally-enforced compulsory drug abstinence programs (CDAP), despite limited evidence on its effectiveness. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the association between CDAP exposure and HIV and overdose-related risk.

Methods: We searched PubMed, EBSCOhost and Sociological Abstracts for studies that contained an individual-level association between CDAP exposure and related HIV or overdose risks, with no date restrictions. Meta-analyses were conducted on data abstracted from eligible studies, using pooled random-effects models and I-squared statistics. We assessed quality of the studies across 14 criteria for observational studies.

Results: Out of 2,226 abstracts screened, we included 8 studies (5253 individuals/776 events) across China, Mexico, Thailand, Norway, and the United States. All but two were cross-sectional analyses, limiting strength of observed associations. In the two studies that reported association between CDAP and HIV seropositivity or receptive syringe sharing, findings were inconsistent and did not indicate that those with exposure to CDAP had increased odds of HIV or syringe sharing. However, we found the odds of experiencing non-fatal overdose in lifetime and in the last 6–12 months were 2.02 (95% CI 0.22 – 18.86, p = 0.16) to 3.67 times higher (95% CI 0.21 – 62.88, p = 0.39), respectively, among those with CDAP exposure than those without.

Conclusion: Research assessing HIV risk associated with CDAP is scant and inconclusive, while evidence of robust associations between CDAP and overdose risk continues to mount. More rigorous, longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the causal relationships between CDAP and these health outcomes. Aside from the growing evidence base on collateral harms, ethical considerations dictate that voluntary, evidence-based drug treatment should be prioritized to address the drivers of excess morbidity and mortality among people who use drugs.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, health outcomes associated with drug use, such as HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and overdose constitute significant sources of morbidity and mortality facing people who use drugs (PWUD), (Mathers et al., 2013). There are an estimated 15.6 million people who inject drugs (PWID) globally, among whom 17.8% are estimated to be living with HIV and 53% are HCV-antibody positive (Degenhardt et al., 2017). Injection drug use (IDU) has been identified as a primary driver of HIV epidemics in numerous settings, with drug overdose contributing to competing mortality risks for these groups (El-Bassel, Shaw, Dasgupta, & Strathdee, 2014; Gilbert et al., 2013; Mathers et al., 2013; Mathers et al., 2008; Peters et al., 2016). Access to and retention in evidence based pharmacological drug treatment, such as methadone or buprenorphine-based treatment, has been found to substantially reduce the risk of overdose mortality and HIV and HCV acquisition (Bahji, Cheng, Gray, & Stuart, 2019; Ma et al., 2019; MacArthur et al., 2012; Platt et al., 2017; Sordo et al., 2017). In addition, numerous empirical and modeling studies have found synergistic outcomes when evidence-based drug treatments are integrated with the provision of HIV treatment and prevention services (Cepeda et al., 2020; Cepeda et al., 2018; Karki, Shrestha, Huedo-Medina, & Copenhaver, 2016; Low et al., 2016; Mlunde et al., 2016; Stone et al., 2021 (in press)). A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis by Low and colleagues found that the provision of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) increased recruitment, coverage, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and increased the odds of achieving viral suppression (Low et al., 2016). Recent systematic reviews have found positive associations between MOUD and ART initiation, retention, and HIV testing (Mlunde et al., 2016).

Despite numerous potential benefits, evidence-based drug treatment is not universally available nor publicly accepted in many countries with significant populations of PWID (Degenhardt et al., 2019; Eibl, Morin, Leinonen, & Marsh, 2017; Mendelevich, 2011; Wakeman & Rich, 2018; Zelenev, 2018). Instead, in many settings, compulsory drug abstinence programs (CDAP, often referred to as compulsory/mandatory/involuntary/forced/coerced drug treatment), are increasingly implemented to address drug use (Sinha, Messinger, & Beletsky, 2020; Thomson, 2010). In addition to limited evidence on its effectiveness in reducing drug use (Werb et al., 2016), substantial concerns over potential human rights violations occurring within CDAP have subsequently been raised (Amon, Pearshouse, Cohen, & Schleifer, 2013; International Labour et al., 2012; Open Society Foundation, 2011; Sinha et al., 2020).

The characteristics of CDAP and their implementation across settings are highly variable (Werb et al., 2016). For example, over the past several decades, the United States has expanded the number of states with “civil commitment for substance abuse” statutes (Christopher, Pinals, Stayton, Sanders, & Blumberg, 2015). These statutes have been deployed through “treatment facilities”, where an individual who uses drugs can be involuntarily detained for drug use upon request from family members, clinicians, prosecutors, or a judge’s order, upon sufficient evidence that the individual poses a threat to themselves or others due to their drug use (Christopher et al., 2015). These facilities range from residential treatment centers to repurposed jail spaces, some of which are operated by the states’ Departments of Corrections (Beletsky & Tomasini-Joshi, 2019). CDAP are also implemented widely in southeast Asia, such as Thailand, China, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, where detainee estimates range from 2,000 in Laos to 170,000 in China (Kamarulzaman & McBrayer, 2015). Concern about these facilities have been raised by human rights organizations due to reported instances of forced labor, physical and sexual abuse, as well as a lack of access to evidence-based treatment (Agence, 2017; Amon et al., 2013; Human Rights Watch, 2010; Jacobs, 2010; Open Society Foundation, 2011). In Sweden, compulsory drug treatment is part of country’s more punitive and prohibitionist approach to drug use relative to other European Union countries (Hallam, 2010; Levy, 2017; Palm & Stenius, 2002). Mexico has a legal framework for the implementation of involuntary drug treatment programs in which these programs are certified by the Mexican government. They include the provision of medically-based care by a physician, and involuntary admissions require a judge’s approval (Rafful et al., 2020). However, most CDAP are privately operated, utilize approaches found ineffective when applied to opioid use and other substance use disorders, such as 12-step models based on Alcoholic Anonymous, and operate with little government oversight (Rafful et al., 2020). Involuntary admissions to these programs often occur extrajudicially with individuals typically forced into the programs by family members or law enforcement (Rafful et al., 2020).

There is a robust body of evidence that incarcerated PWUD face an elevated risk of overdose immediately following release from prison (Binswanger, Blatchford, Mueller, & Stern, 2013; Bukten et al., 2017; Merrall et al., 2010), as well as significant HIV and HCV-related risks post-release (Adams et al., 2011; Adams et al., 2013) specifically among PWID. However, studies also have shown that this substantial excess mortality risk in the month following prison release is removed if MOUD is provided in prison (Degenhardt et al., 2014; Green et al., 2018; Marsden et al., 2017). The similarities between CDAP and carceral settings indicate that PWUD could face aggravated health risks after release from CDAP. Yet, evidence on the effects of CDAP on HIV and overdose remains sparse. Previous systematic reviews of the effectiveness of CDAP have focused primarily on societal harms (e.g., incarceration, recidivism), finding limited effectiveness (Werb et al., 2016). Systematic, quantitative findings of the effect of CDAP on HIV and overdose outcomes are lacking. The objective of this analysis was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between exposure to CDAP and HIV and overdose-related risks among PWUD.

METHODS

Definition of CDAP and non-CDAP exposure

We defined exposure to CDAP among PWUD as ever experiencing legal or extrajudicial coercion and detention in a facility whose primary function is to manage a persons’ drug use predominantly by enforced detoxification to achieve abstinence. The conditions individuals experience in CDAP vary widely, spanning a spectrum that includes facilities that closely resemble carceral settings to those that operate with voluntary inpatient drug treatment programs (Cramer & Freyer, 2017; Csete et al., 2011; Pasareanu, Vederhus, Opsal, Kristensen, & Clausen, 2016). Despite the heterogeneity in the quality of conditions within CDAP, the involuntary physical confinement of the admitted individuals is a consistent feature. Comparison groups were PWUD who reported no history of detention in CDAP. This could include PWUD who were receiving or who had received MOUD or other voluntary addiction treatment, such as methadone maintenance therapy, as well as PWUD in the community who were not in drug treatment programs with no history of drug use treatment.

Systematic Literature Review

We utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to accomplish the literature review aims (Moher et al., 2009). We conducted two searches with CDAP as the main exposure, one search focusing on HIV or injection-related outcomes and the second search focusing on overdose-related outcomes. We searched three bibliographic databases: PubMed, Sociological Abstracts and EBSCO Host that encompass both health and sociological literature. Inclusion of articles in the review was dependent on the study reporting a quantitative association between CDAP and HIV risk and overdose-related outcomes following PICO (patient, intervention, control/comparison, outcome) guidelines (Methley, Campbell, Chew-Graham, McNally, & Cheraghi-Sohi, 2014). The patient population was defined as PWUD or PWID and our review was not limited to just people with opioid use disorder). The intervention was exposure to CDAP while the control/comparison group had no history of CDAP. We specified two primary outcomes: 1) HIV incidence/seroprevalence and 2) fatal/non-fatal drug overdose. As secondary outcomes, we considered several injection-related behaviors, such as receptive syringe or needle sharing. Inclusion criteria were reporting (1) primary, individual-level quantitative data, not based on estimated outputs from modeling or cost- effectiveness analyses, and (2) participants reporting prior exposure or current detainment in a CDAP (no restrictions on timeframe of exposure). Studies were excluded if they only presented qualitative data, did not report primary data (e.g., systematic review), or did not use PWUD or PWID as the unit of analysis (e.g., ecological study).

The first search focused on identifying studies which documented an association between HIV-related outcomes and exposure to CDAP. The second search focused on identifying literature which documented an association between CDAP and risk of fatal/non-fatal overdose. AV and CM screened the abstracts independently and then cross-checked approximately 10% of abstracts to determine the agreement in abstracts selected for full text review. The reviewers agreed on approximately 90% of abstracts that were cross-checked, and a senior team member adjudicated any conflicts.

For all eligible studies, we utilized coding forms adapted from a previous systematic review (Baker et al., 2020) and abstracted HIV-outcome data (seroprevalence and injection risk behaviors) and overdose data (nonfatal or fatal, irrespective of time period) stratified by exposure to CDAP (irrespective of time period). Reported frequencies and analytic sample sizes from the papers were used to calculate unadjusted odds ratios for HIV-related and overdose outcomes based on exposure to CDAP with unexposed, defined as no experience with CDAP, as the referent group.

To assess the quality and potential biases of the eligible studies we used the NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies form for each eligible study (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute). Each study was reviewed and scored independently by two reviewers (AV and CM) across 14 criteria and given an overall rating of good, fair or poor (additional details provided in supplement).

Meta-analysis

We conducted meta-analyses with relevant data across included studies when possible, using the R package “meta” (Harrer, Cuijpers, Furukawa, & Ebert, 2019; “meta: General Package for Meta-Analysis,”). Our analyses utilized the Mantel-Haenszel method for random-effects model to obtain the pooled estimates of receptive syringe sharing, HIV seroprevalence and overdose outcomes associated with CDAP. We applied the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for estimators for tau-squared, which results in more conservative measures of variance and is recommended when conducting pooling a small number of studies or studies with substantial heterogeneity (Harrer et al., 2019). Forest plots for each pooled analysis were presented. However, due to inconsistent time frames of published HIV outcomes and the heterogeneity of the samples for overdose outcomes, we only conducted the meta-analysis for CDAP exposure and HIV seroprevalence, receptive syringe sharing, and non-fatal overdose.

RESULTS

Search results

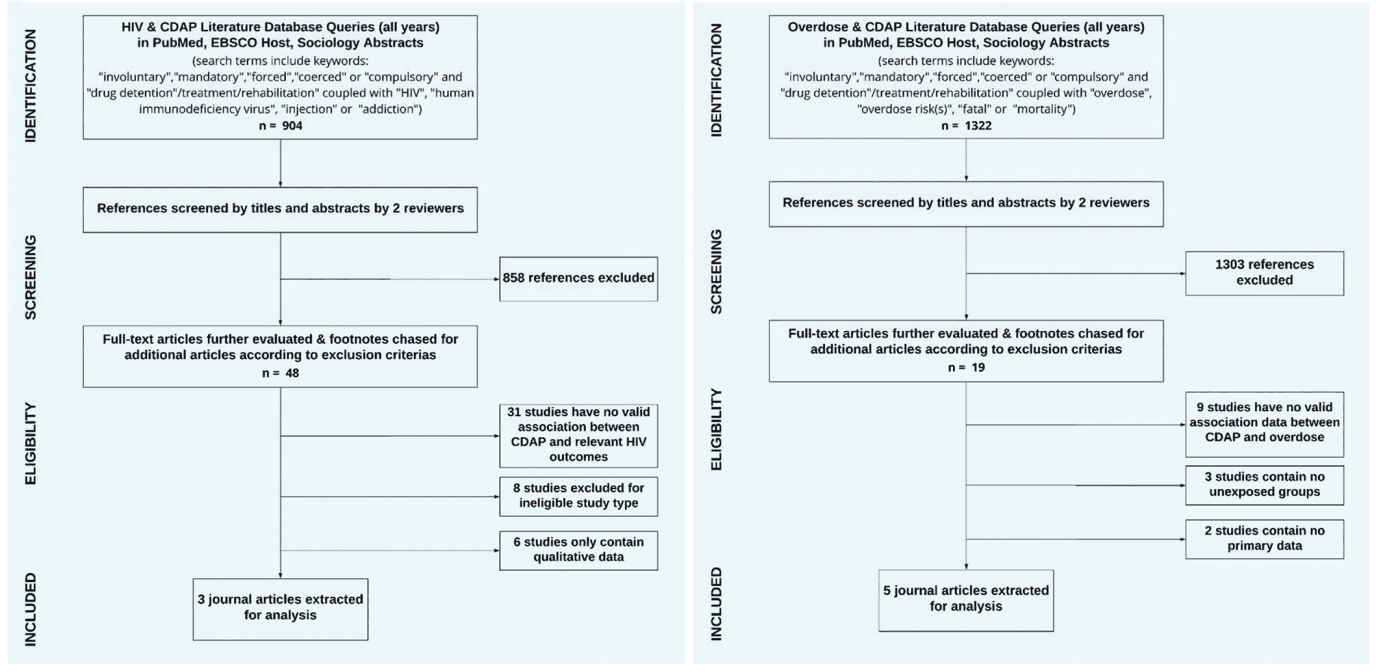

Our first search on CDAP and HIV outcomes returned a total of 904 references. After screening abstracts and removing ineligible papers and duplicates, 46 articles remained for full-text review. We included 3 articles with relevant data (Figure 1), excluding 31 studies with no control group or valid association (per inclusion criteria) between HIV seroprevalence or syringe sharing and CDAP, 8 with ineligible study types, and 6 that only reported qualitative data.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Charts for HIV & CDAP (left) and Overdose & CDAP (right) literature systematic review

In the second search on CDAP and overdose outcomes, there were a total of 1322 references returned. Following the title and abstract review, 19 papers were selected for full text review, of which 14 were determined to be ineligible for data abstraction. Of the fourteen deemed ineligible, 9 did not report overdose data, three did not have an unexposed comparison group, and two were review papers that did not report primary data. Five eligible articles providing data on CDAP and overdose risks were included in the final analysis.

Quality of included studies

Using the NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, we determined that all 3 included studies with relevant HIV outcomes were of poor quality, while four of five studies with overdose outcomes received a poor quality ratings and one earned a fair rating. Reasons for the poor quality ratings included reliance on self-report for exposure and outcome measures, lack of adjustments for key potential confounders in multivariable models, and cross-sectional study designs which lacked measures of exposure prior to measures of outcomes.

HIV seroprevalence, receptive syringe sharing, and CDAP exposure

A summary of the characteristics of the three studies is found in Table 1. No studies identified in our review measured HIV incidence. All studies were published after 2010 with data typically collected 3–4 years prior to publication. Of the three studies, two were conducted in China (Lin et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011), with an additional study conducted in Mexico (Borquez et al., 2018). Two of the three studies consisted of cross-sectional analyses, while one was longitudinal. The reported time frames for HIV seroprevalence and receptive syringe sharing varied between “at time of survey,” “last 6 months” or “ever.” Similarly, the time frames for CDAP varied, with participants either having any history of being in CDAP or having been in CDAP within the last 6 months or at the time of survey.

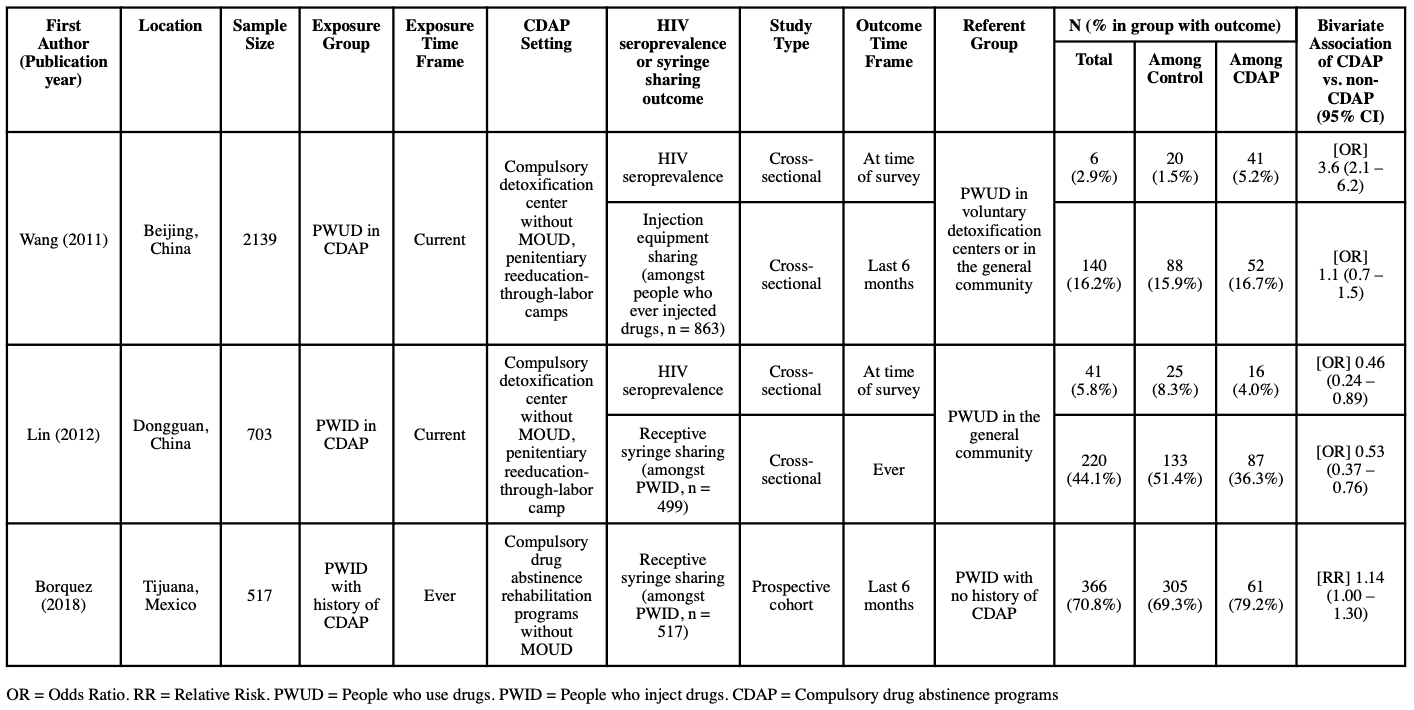

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included CDAP-HIV Risk Outcome Studies

Two studies measured the associations between CDAP exposure and HIV seroprevalence via blood testing at the time of data collection, with conflicting results (Lin et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011). Wang et al. conducted a cross- sectional survey of PWUD at three settings in China: mandatory detoxification centers, and either voluntary detoxification centers or the general community. The study found that 5.2% of those in CDAP were seropositive for HIV, compared to only 1% testing positive among those not in CDAP, with bivariate analyses indicating the odds of being HIV positive were 3.6 times higher for those in CDAP than those who were not exposed (OR: 3.6; 95% CI: 2.1 – 6.2). By contrast, a cross-sectional survey comparing PWUD in a compulsory detoxification center in Dongguan, China and PWUD in the community found that only 4% of PWUD in CDAP were HIV seropositive, compared to 8.3% of PWUD in the community. Overall, the bivariate analysis found a lower odds of HIV seropositivity (OR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.24 – 0.89) among those exposed to CDAP than PWUD in the general community.

Three studies reported receptive syringe sharing as an outcome variable, with two studies measuring syringe sharing in the last 6 months (Borquez et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2011) and one study measuring any history of syringe sharing (Lin et al., 2012). Results from Wang et al showed that among those in CDAP who also ever injected drugs, 16.7% (n=52) reported having shared injection equipment over the last 6 months, compared to 15% among those who were in voluntary detoxification or community-based programs. For this study, there was no clear association between exposure to CDAP and injection equipment sharing (OR: 1.1 [95% CI: 0.7 – 1.5]). Lin et al also compared syringe sharing among PWID in CDAP and those in voluntary treatment, finding that 4% of those in CDAP reported any history of sharing syringe compared to 8% of those in voluntary treatment (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.37 – 0.76). Borquez et al, utilized data from 517 PWID in Mexico, comparing 77 who had been in CDAP during their most recent rehabilitation experience to 440 who had either never received treatment/rehabilitation or who had done it voluntarily. They found that 79% of those who had ever been in CDAP had also reported receptive syringe sharing in the last 6 months, while 69% of those not exposed to CDAP had reported the same (RR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.0 – 1.3).

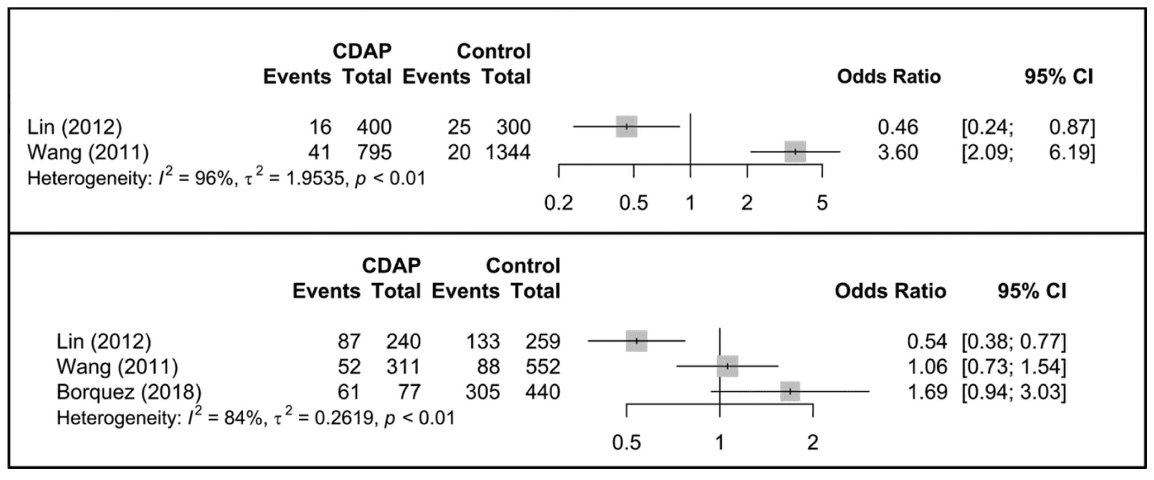

Due to inconsistent time frames for receptive syringe sharing outcomes in Lin et al and Borquez et al, and the differing outcome definition of “injection equipment sharing” in Wang et al compared to the other two studies, we did not calculate a pooled estimate for the association between CDAP and receptive syringe sharing. The pooled analysis of HIV seroprevalence from Lin et al and Wang et al indicated those in CDAP were approximately 30% more likely to have HIV at the time of study than those who were not in CDAP, however this was not statistically significant (p=0.84) (Figure 2) and had high heterogeneity (I2 = 96%, τ2 = 1.95, p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Summary analysis of CDAP associations with HIV seroprevalence (upper) and receptive syringe sharing risk (lower)

Overdose-related outcomes and CDAP exposure

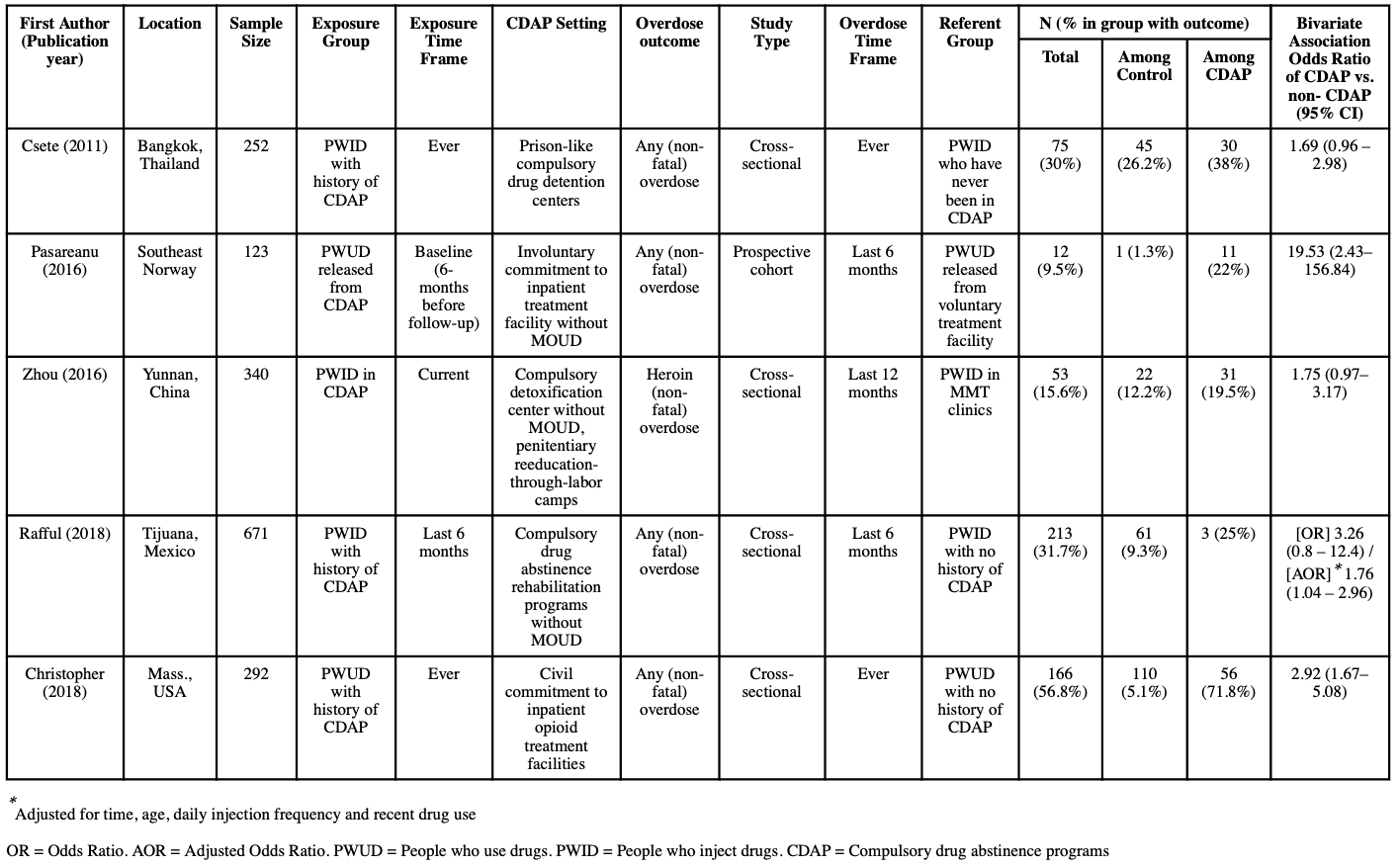

An overview of the five eligible articles for the overdose-related outcomes is found in Table 2. Despite the limited number of eligible articles, the data abstracted represented a geographically diverse sample, with two studies from Asia (Csete et al., 2011; Zhou, Luo, Cao, Zhang, & Wu, 2016), two from North America (Christopher, Anderson, & Stein, 2018; Rafful et al., 2018), and one from Europe (Pasareanu et al., 2016). Among the overdose data reported in the five eligible articles, four presented data on any non-fatal overdose (Christopher et al., 2018; Csete et al., 2011; Pasareanu et al., 2016; Rafful et al., 2018) while the fifth presented data on incidence of non-fatal heroin overdose (Zhou et al., 2016).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included CDAP-Overdose Studies

Two studies reported associations between CDAP exposure and non-fatal overdose events both within the 6 months prior to data collection (Pasareanu et al., 2016; Rafful et al., 2018). A prospective cohort study conducted in Norway (Pasareanu et al., 2016) surveyed patients upon their release from either a voluntary or compulsory stay at an inpatient drug treatment facility and again at a 6 month follow-up visit. At follow-up, 11 of 51 participants (22%) from the compulsorily admitted group reported a non-fatal drug overdose during the 6 months follow-up period, compared to only one reported non-fatal overdose over the same period among the 72 patients (1%) in the voluntarily admitted group. Based on these estimates, we calculated an unadjusted odds ratio between participants released from CDAP at baseline and non- fatal overdose in the 6-month follow-up period of 19.5 (95% CI: 2.4–156.8) compared to those who were voluntarily admitted. Rafful et al. examined a longitudinal study of 671 PWID in Tijuana, Mexico, also finding a statistically significant increase in risk of non-fatal overdose in the past 6 months among those with past CDAP exposure compared to no exposure (AOR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.04–2.96).

One study assessed association between current CDAP exposure and non-fatal heroin overdose in the previous year (Zhou et al., 2016). Zhou et al presented cross-sectional survey data for participants in two compulsory drug rehabilitation centers and four methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clinics in Yunnan, China. The study found that 53 patients (15.6%) reported having an overdose, as opposed to 12.2% of those in MMT. The calculated odds ratio based on these estimates was 1.75 (95% CI: 0.97 – 3.17).

Two studies reported associations between CDAP and ever experiencing a non-fatal overdose, and both reported increased odds of non-fatal overdose among those with exposure to CDAP (Christopher et al., 2018; Csete et al., 2011). Csete et al. investigated CDAP experiences of PWID in Bangkok, Thailand. Of the 252 participants, 80 (37%) reported a history of detention in CDAP. Among those ever detained in CDAP, 38% (n=30) reported ever experiencing an overdose, compared to 27% among those who did not report a history of compulsory drug detention. Based on these reported frequencies, we calculated that exposure to CDAP was associated with 69% higher odds (95% CI: 0.96 – 2.98) of ever experiencing a non-fatal overdose compared to those with no history. Christopher et al. examined the experiences of PWUD with a history of CDAP exposure in Massachusetts, United States by surveying 292 PWUD, among whom 78 had a history of CDAP detention. Among those who were exposed to CDAP, 56 (72%) had ever experienced a non-fatal overdose compared to 110 (51.4%) of the 214 who had no experience with CDAP through the form of civil commitment, resulting in an unadjusted odds ratio of 2.41 (95% CI: 1.37–4.22).

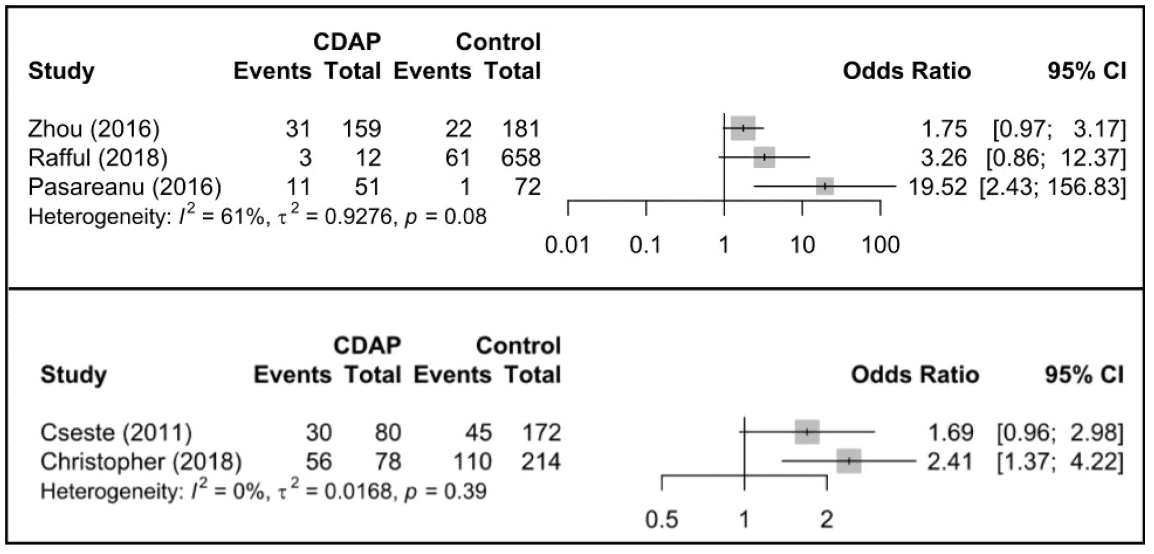

We pooled the data from Pasaraenu et al, Zhou et al, and Rafful et al to provide an estimate of non-fatal overdose risk within the last 6–12 months as associated with CDAP exposure (Figure 3). A pooled estimate of lifetime non-fatal overdose risk associated with CDAP was also calculated accordingly using data from Csete et al and Christopher et al (Figure 3). Both pooled estimates did not reach statistical significance, resulting in an OR of 3.67 (95% CI: 0.21 – 62.88) for past 6–12 months non-fatal overdose risk with substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 61%, τ2 = 0.93, p = 0.08), and an OR of 2.02 (95% CI: 0.22 – 18.86) for lifetime non-fatal overdose risk with low heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, τ2 = 0.02, p = 0.39) .

Figure 3:

Summary analysis of CDAP associations with non-fatal overdose risk in last 6 months (upper) and in lifetime non-fatal overdose risk (lower)

DISCUSSION

Given the associations between incarceration (settings typically characterized by forced abstinence similar to CDAP) and HIV and overdose related outcomes (Merrall et al., 2010; Stone et al., 2018), we hypothesized that CDAP exposure would also be associated with these outcomes. Despite the increasing utilization of CDAP, we found few quantitative evaluations of HIV and overdose risk post release. We identified mostly cross-sectional studies which relied on self-reported exposure and outcome measures. Most were assessed to be of poor/fair quality and subject to bias and confounding. Data in most of the eligible studies on HIV outcomes indicated an increased HIV prevalence and injection risk behaviors associated with CDAP. However, heterogeneity between studies precluded us from pooling the majority of the results. In addition, most studies were cross-sectional, several of which were conducted while participants were detained in a CDAP facility. Thus, participants might have seroconverted prior to their admission into CDAP. The exception to this trend was the study by Lin et al. which reported a 0.48 odds of prevalent HIV infection among those exposed to CDAP compared to unexposed (Lin et al., 2012). However, we noted significant differences between the two exposure groups that could explain this finding. For example, individuals in the non-CDAP group were older and more likely to share syringes (Lin et al., 2012), which likely confounded the association between CDAP and HIV. Additional evidence from a study conducted in Guangxi Province, China, which was excluded from our analysis due to an inconsistent exposure group, found no association between the number of times participants had been in CDAP in the past and needle/syringe sharing, but did find a positive association the number of CDAP admissions and general injection equipment sharing (cooker, cotton, rinse water, or drug solution sharing) (Chen et al., 2013). Nonetheless, our results indicated a lack of support for the role of CDAP in reducing potential injection risk behaviors.

Our search also identified studies presenting data on CDAP and other HIV treatment outcomes, finding PWID in CDAP were more likely to have avoided healthcare (Kerr et al., 2014), more likely to have received an HIV test (Wegman et al., 2017), less likely to have received ART treatment (Hayashi et al., 2015) compared to those in non-CDAP settings. These studies were excluded from this review as they did not meet eligibility criteria but nonetheless indicate a potential deleterious effect of CDAP on PWID at risk or living with HIV. In contrast, integrating ART with MOUD is associated with a 45% increase in the odds of viral suppression compared to those not in MOUD, 54% increase in ART coverage (Low et al., 2016), and a 54% reduction in risk of HIV transmission (MacArthur et al., 2012). Thus, HIV-related injection risks amongst PWID should be addressed with voluntary evidence-based treatment.

Regarding non-fatal overdose, data from two of the five studies identified in our review resulted in a statistically significant association between exposure to CDAP and non-fatal overdose. Although they did not reach statistical significance, calculated odds ratios from the remaining three studies indicated a similar magnitude of overdose risk associated with CDAP exposure. After pooling the estimates, those exposed to CDAP had 2.02 (lifetime) to 3.67 (past 6– 12 months) higher odds of non-fatal overdose compared to those with no CDAP exposure. Findings from the overdose review indicate, at a minimum, that it is unlikely CDAP reduces the risk of overdose for PWUD and PWID post-release. In addition, the one study (Pasareanu et al., 2016) from our overdose review in which exposure to CDAP clearly and immediately preceded overdose outcome measures had the strongest association between CDAP exposure and non-fatal overdose. This result is consistent with evidence of the significantly higher risks of overdose for PWUD following incarceration or dropping out of drug treatment (Degenhardt et al., 2019; Hickman et al., 2018; Mital, Wolff, & Carroll, 2020).

As of 2016, 37 U.S. states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws allowing involuntary commitment for individuals diagnosed with drug use disorders and alcoholism, with varying degrees of enforcement (Christopher et al., 2015). In Massachusetts, where civil commitment (i.e. “Section 35”) is actively enforced, there has been a substantial increase in the number of commitments since 2014 (Messinger & Beletsky, 2021). Data from a 2016 report by the Massachusetts Office of Health and Human Services also showed that those in involuntary treatment had a higher risk of fatal overdose in the 1–3 years after the treatment, compared to those who sought treatment voluntarily (RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.85–2.66, p<0.001) (Executive Office of & Human Services Department of Public, 2016). Although we did not include this estimate in our main analysis as we did not systematically review the grey literature, this report is consistent with findings by Christopher et al. that a history of civil commitment of people who use opioids is associated with increased non-fatal overdose risk (2018). This study also reported that only 19.5% of those committed received any medication treatment for their opioid use, and only 7.7% received medication treatment following their release from civil commitment (Christopher et al., 2018). These low rates of medication access during detention, compounded by lack of care continuation post-detention likely contribute to elevated overdose and other health risk (Sinha et al., 2020). Civil commitment facilities in Massachusetts, where men are primarily housed in settings managed by the Department of Corrections, have also become COVID-19 hot spots. This highlights additional health risks imposed by congregate detention in the name of drug treatment (Messinger & Beletsky, 2021). Drawing on evidence of harm, legal advocacy efforts in Massachusetts, including lawsuits and proposed legislation, have forced prisons, jails and other detention settings to allow the use of MOUD (Sinha et al., 2020). Similar efforts have also sought to completely bar the use of correctional facilities to house civil commitment patients (Becker, 2020). In other countries including Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, as well as in Mexico, access to primary healthcare services in CDAPs has been shown to be limited, if available, and reports of medical negligence and physical harm further highlight the urgent need to transition to integrated health and voluntary evidence-based drug treatment services (Rafful et al., 2020; Tanguay et al., 2015; Thomson, 2010). In addition, the lack of facilities offering evidence- based treatment for PWUD, particularly in LMIC, highlights the need for the integration of evidence-based drug treatment, such as MOUD into other health programs such as ART. The integration of ART and MOUD can be a means of expanding access to pharmacological therapies for PWUD in underserved areas (Cepeda et al., 2020; Karki et al., 2016; Low et al., 2016; Mlunde et al., 2016)

This review also highlights the diversity in CDAP with respect to geography and characteristics of these institutions. In China, CDAP operate under the jurisdiction of public security agencies and detainment occurs in penitentiary-like conditions (Wang et al., 2011). Non-CDAP settings in China differ locally, ranging from community- based treatment programs to voluntary drug detoxification in similar centers (Lin et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011; Zhang, Tan, Hao, & Deng, 2017). In Southeast Asia, compulsory drug abstinence programs often operate within detention institutions specifically for drug abstinence, while non-compulsory programs include voluntary residential treatment centers and community-based programs including MOUD (Csete et al., 2011; Hayashi et al., 2015; Kerr et al., 2014; Vuong et al., 2017; Wegman et al., 2017). Given the higher propensity of enforcement of CDAP in these settings, especially China, there is an urgent need to better link CDAP custodial and discharge data with post-release HIV and overdose outcomes.

The diverse implementation of CDAP is reflected by the varying results and the localized risks of HIV and overdose within these settings. This prompts the need for future work to harmonize data collection and establish more uniform definitions and guidelines when studying the impact of CDAP. Our review differentiated between carceral settings and CDAP facilities, but as discussed previously, CDAP and traditional carceral settings share significant characteristics and post-release risks encountered by PWUD. Conceptual frameworks have been developed to guide research investigating the risk environments facing PWUD post-release from carceral settings (Joudrey et al., 2019) and similar frameworks should be developed to guide research on PWUD released from CDAP.

Given the grave health and human rights concerns raised by many of the studies we reviewed, there is a pernicious gap between empirical evidence and practice in the realm of CDAP. Positive changes to improve CDAPs or shrink their footprint have been anemic. This warrants increasing collaboration with legal and human rights groups, while thinking beyond traditional translational efforts. Such measures may include lawsuits anchored in national and international legal norms, legislative advocacy invoking the clout of professional medical organizations, and other intersectional efforts designed to catalyze and accelerate change in this troubling realm of substance use treatment (Sinha et al., 2020).

LIMITATIONS

Our search strategy utilized key terms (e.g. coerced, involuntary, forced) to identify studies that included CDAP as an exposure variable. However, some studies may not have included information on coercive/involuntary elements of the program studied, characterizing them only as ‘drug treatment’ facilities, leading to their omission from our search. This is of particular concern in countries (e.g. China) where CDAPs represent a significant proportion of ‘drug treatment’ facilities. Most eligible studies were cross-sectional and could not provide strong evidence of causation (i.e. cannot rule out reverse causation). In addition, several cross-sectional studies included in our review had exposure and outcome chronology reversed including studies measuring outcomes with participants currently detained. This lack of causal evidence combined with inconsistent and insufficient control for confounding factors, lack of consideration of selection biases between intervention and comparison groups, as well as reliance on self-reports for outcome measures (especially overdose outcomes), limits our ability to make strong inferences on the temporality and causality between CDAP exposure and the evaluated outcomes. There were no trials and no natural experiments or use of linked data sets that could seek to emulate a trial. Depending on standard of care for treatment for opioid use disorder, it could be unethical to conduct a controlled study that randomizes individuals to CDAP or voluntary MOUD (if available), the gold-standard treatment for opioid use disorder.

Thus, it is possible that the relationship between CDAP and these outcomes could be affected by selection bias and confounded by other unmeasured factors, such as more frequent engagement of high-risk behaviors among those exposed to CDAP compared to lower risk individuals not exposed to CDAP. Other possible confounders could include that individuals detained in CDAP may experience greater structural determinants of health, such as homelessness, poverty, unemployment or have less social support. Usually with small poorly controlled observational studies there is a bias towards publishing “positive findings”. We did not find this in our review. Nonetheless, the findings from our review and meta-analysis suggest no significant protective effects of CDAP regarding HIV and overdose risks. Most studies identified also utilized self-reported measures which could be imprecise and lack rigor. However, we identified associations between exposure to CDAP and HIV seroprevalence data collected via blood draw, rather than self-report. We also identified high heterogeneity which could be due to differences in study design, differences in measures of temporality (e.g. ever overdosed vs overdose in the last 6 months), and small sample size. Another possible source of heterogeneity may be differences in overdose risk between people with opioid use disorders and people with other, non- opioid, substance use disorders (e.g. alcohol use disorder or stimulant use disorder) Lastly, non-fatal overdose events were also self-reported and subjected to the same limitations. However, mortality data based on death certificates collected by the state of Massachusetts and Sweden indicated associations between exposure to CDAP and elevated mortality rates due to drug overdose (Bukten et al., 2017; Hallam, 2010; Levy, 2017; Palm & Stenius, 2002). Even though these studies were not eligible for data abstraction due to the lack of an unexposed comparison group, they offer further potential research directions to examine elevated overdose risk or other related mortality risks among those in CDAP.

CONCLUSION

We found no evidence to suggest that CDAP significantly reduces injection drug related and overdose risks. Rather, the results of our systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that CDAP might be associated with increased HIV-related injection and overdose risks. Available evidence is limited, and further research is needed to assess these relationships more rigorously. Given ethical concerns presented by a controlled trial of compulsory abstinence, future research should utilize longitudinal designs and leverage natural experiments. Additional empirical, longitudinal research examining the health outcomes of individuals during and after CDAP is needed. Despite its limited nature, the current body evidence suggests at a minimum, CDAP is not associated with reduced post-release HIV, HCV, and overdose risks. In addition to their limited effectiveness, these programs present serious human rights concerns. Policymakers should direct resources towards evidence-based harm reduction programs such as voluntary MOUD which has a robust evidence- base indicating multiple benefits with respect to preventing HIV and HCV transmission, HIV treatment outcomes, and reducing overdose risks. In settings where CDAPs persist, collection of observational data on health outcomes is warranted along with greater harmonization, such as reporting outcome data to national health agencies to monitor effectiveness. This could improve program transparency, allowing for regulatory agencies as well as human rights monitoring and legal advocacy groups to respond to potential abuses.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01DA043421), Fogarty International Center, NIAID/NIDA (R01 AI147490), and UCSD Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI036214). AB acknowledges support from NIDA (DP2 DA049295). LB also acknowledges funding by Open Society Foundations’ Public Health Program grant. The funders had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of findings, writing of the manuscript, or submission of the paper for publication.