Abstract

Aims: Maintaining abstinence from alcohol use disorder (AUD) is extremely challenging, partially due to increased symptoms of anxiety and stress that trigger relapse. Rodent models of AUD have identified that the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) contributes to symptoms of anxiety-like behavior and drug-seeking during abstinence. In humans, however, the BNST’s role in abstinence remains poorly understood. The aims of this study were to assess BNST network intrinsic functional connectivity in individuals during abstinence from AUD compared to healthy controls and examine associations between BNST intrinsic functional connectivity, anxiety and alcohol use severity during abstinence. Methods: The study included resting state fMRI scans from participants aged 21–40 years: 20 participants with AUD in abstinence and 20 healthy controls. Analyses were restricted to five pre-selected brain regions with known BNST structural connections. Linear mixed models were used to test for group differences, with sex as a fixed factor given previously shown sex differences. Results: BNST-hypothalamus intrinsic connectivity was lower in the abstinent group relative to the control group. There were also pronounced sex differences in both the group and individual analyses; many of the findings were specific to men. Within the abstinent group, anxiety was positively associated with BNST-amygdala and BNST-hypothalamus connectivity, and men, not women, showed a negative relationship between alcohol use severity and BNST-hypothalamus connectivity. Conclusions: Understanding differences in connectivity during abstinence may help explain the clinically observed anxiety and depression symptoms during abstinence and may inform the development of individualized treatments.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 15 million Americans had alcohol use disorder (AUD) in 2019 (SAMHSA, 2019), resulting in substantial individual, family, and societal burdens. Although treatments for AUD exist, the majority of individuals relapse within a year of treatment (Durazzo and Meyerhoff, 2017; Sliedrecht et al., 2019), highlighting the difficulty of remaining sober and achieving long-term treatment success. Many of the factors contributing to relapse are thought to arise from brain changes related to chronic alcohol use (for review see Koob and Volkow, 2016). Specifically, chronic alcohol use leads to changes in the neural circuits that govern reward, stress and anxiety, and executive function (Koob and Volkow, 2016). These changes lead to decreased sensitivity to reward and increased sensitivity to stress during abstinence, which together create a powerful vulnerability for relapse (Becker, 2012; Cui et al., 2015; Mantsch et al., 2016). Decades of research have elucidated how the reward circuit is altered in AUD; however, much less is known about alterations in the stress and anxiety circuitry. Given the importance of anxiety in relapse, determining how anxiety network connectivity differs during abstinence could identify individuals at risk of relapse and help guide new treatments.

Studies in rodent models of abstinence have identified the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) as a brain region responsible for anxiety-like behaviors during abstinence (Erb and Stewart, 1999; Huang et al., 2010; Koob and Volkow, 2016; Centanni et al., 2019). The BNST is a small, subcortical region with a variety of functions, including stress response, autonomic control, endocrine regulation, feeding behaviors, and sexual behaviors (for review see Lebow and Chen, 2016). During abstinence, BNST cells have markers of increased neural activity (Sharko et al., 2016; Saalfield and Spear, 2019), and infusing the BNST with the stress-related hormone, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), increases anxiety-like behaviors (Huang et al., 2010). Furthermore, anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors related to abstinence are attenuated with disruption of inputs to the BNST (Centanni et al., 2019). The BNST is not only important in the expression of anxiety-like behaviors during abstinence but has also been linked to relapse in other drugs of abuse. For example, blocking CRH receptors in the BNST during abstinence increases drug seeking in substance-dependent mice (Erb and Stewart, 1999; Erb et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2006). For a more comprehensive review of rodent models of the BNST in reinstatement, please see reviews Harris and Winder, 2018 and Mantsch et al., 2016. Despite decades of strong rodent evidence for the BNST’s role in anxiety-like behavior during abstinence and relapse, human studies of BNST function are scarce.

A major reason for the scarcity of studies is that the BNST has been difficult to investigate using in vivo neuroimaging methods in humans due to its small size. Capitalizing on technical advancements, reliable neuroimaging methodologies have been recently established for identifying the BNST in humans (see Avery et al., 2014; Torrisi et al., 2015; Theiss et al., 2017). Using these methods, one initial study has provided evidence that acute alcohol administration dampens BNST responses in humans (Hur et al., 2018). However, the majority of early BNST studies have focused on characterizing major BNST structural and functional connections throughout the brain (Avery et al., 2014; Tillman et al., 2018; Torrisi et al., 2018, 2015). For example, intrinsic functional connectivity has been used to characterize functional connections, as intrinsic functional connectivity is thought to reveal the brain’s underlying functional networks. Combining findings from rodent literature and these early human studies, a group of brain regions appears to form a core BNST network: the amygdala, anterior hippocampus, anterior insula, hypothalamus, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). Establishing BNST structural connectivity and intrinsic functional connectivity in healthy adults laid the foundation for later studies examining the role of the BNST in different psychopathologies. Recent studies provide initial support for altered BNST intrinsic functional connectivity in patients with anxiety- and trauma-related disorders (Cano et al., 2018; Rabellino et al., 2018; Torrisi et al., 2019; Jenks et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2021). The findings from these initial studies are critical, as they establish analogous BNST functions between rodents and humans, and highlight the potential of future translational work in other psychopathologies.

Despite strong animal model evidence for the BNST’s role during abstinence, the BNST network is poorly understood in humans during this period. To date, there has been one study of structural connectivity in the BNST network during abstinence (Flook et al., 2021). This initial structural connectivity study demonstrated stronger overall BNST network connectivity in early abstinence for women but no differences in men (Flook et al., 2021). The sex-specific findings are particularly noteworthy due to clinical evidence that women are more likely than men to experience anxiety during abstinence (Conway et al., 2006) and are more likely to relapse as a result of this anxiety (for review, see Becker and Koob, 2016). A recent cognitive-behavior therapy treatment study demonstrated a positive correlation between insula-BNST intrinsic functional connectivity and the number of drinking days in patients with AUD (Srivastava et al., 2021). Thus, very little is known about BNST intrinsic functional connectivity during abstinence, and, to our knowledge, no studies have examined group differences in BNST connectivity between controls and individuals during abstinence from AUD.

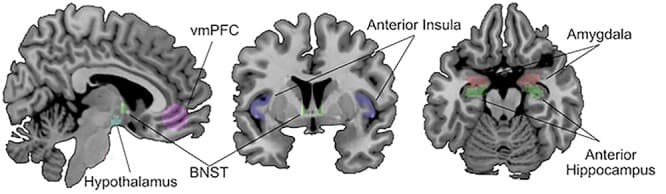

The purpose of this study was to investigate BNST network intrinsic functional connectivity in early abstinence. Intrinsic functional connectivity reflects the amount of synchronized BOLD signal between two brain regions, and highly synchronized regions are thought to represent functional networks. Therefore, comparisons of intrinsic functional connectivity can be used to detect alterations in the brain’s organization. For this initial study, we used a region of interest (ROI) approach and focused on brain regions known to have strong anatomical and functional connections with the BNST (amygdala, anterior hippocampus, anterior insula, hypothalamus, vmPFC; see Fig. 1). ROI approaches are especially useful for initial studies with moderate sample sizes, because they can increase statistical power by leveraging knowledge of anatomical connections to reduce the number of analyses performed. The first aim of this study was to determine whether BNST connectivity is altered during abstinence from AUD. The second aim of this study was to investigate associations between BNST connectivity and self-reported alcohol use severity and anxiety in the abstinence group, as clinical presentations of abstinence have substantial variability that could be reflected in BNST connectivity. Sex was included in the analysis based on previous evidence of sex differences in BNST structural connectivity during abstinence (Flook et al., 2021) and anxiety symptoms during abstinence (Becker and Koob, 2016).

Thus, this study provides a critical first look at the intrinsic functional connectivity of the BNST in people with AUD in early abstinence. In addition, this study addresses a major unmet need in the field: to translate well-described animal models of AUD into humans and determine whether BNST connectivity with other brain regions differs in early abstinence from alcohol.

METHODS

Participants

This study included 40 participants 21–40 years of age: 20 individuals in abstinence from AUD and 20 light social drinkers with no history of AUD as controls. AUD was determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV (First, 1997). Interviews were conducted by study personnel trained by the study psychiatrist and all diagnoses were confirmed by the study psychiatrist (MB).

Controls were light social drinkers recruited using a large institutional recruitment registry. Light social drinkers were defined as individuals with: at least one standard drink in the prior year, no drinking period that met DSM-IV criteria for AUD diagnosis, and no episodes of binge drinking (defined as >5 standard drinks for men and >4 standard drinks for women) within the prior year. Individuals in the abstinence group met criteria for an AUD within the past year and had been abstinent from any amount of alcohol for 30–180 days, as determined by the timeline follow back (Sobell et al., 1988). Participants in the abstinence group were recruited using advertisements, the recruitment registry, and referrals from a local treatment center in Nashville, TN. Patients who are in the early stages of abstinence from AUD are extraordinarily difficult to recruit. We took significant care in selecting a defined period of abstinence to balance feasibility and scientific rigor. Ultimately, the desired range of the abstinence period targeted early abstinence, during which withdrawal symptoms shift from physical withdrawal symptoms to negative affect. Similar studies of patients in recovery have similar, if not broader, ranges of abstinence relative to our selected period. For example, one cohort of patients referenced in highly cited papers (Camchong et al., 2013a, 2013b) included a short-term abstinence group with a duration of abstinence of 72.59 ± 18.36 days who were compared with a long-term abstinence group with a duration of abstinence of 2888.78 ± 2848.14 days. Orban et al. (2013) included patients abstinent from alcohol over a range of 15–893 days. The individuals collected for this sample represent a unique and important subset of patients with AUD. Individuals in the AUD group were primarily recruited from a local community health program, such that the patients were closely followed but also experiencing the daily stressors and anxiety that accompany recovery outside of an inpatient unit or residential program.

Exclusion criteria for both groups were major medical illness or history of traumatic brain injury, contraindications to MRI, or current or lifetime history of a psychotic disorder. In addition, exclusion criteria for the control group included use of psychoactive medication within the last 6 months, lifetime history of alcohol or substance use disorder, or lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder. Additional exclusion criteria for the abstinence group included a current psychiatric disorder, except depression or anxiety; current use of psychoactive medication, other than a stable dose of SSRI or SNRI; or current drug or alcohol use (except nicotine). Participants self-reported alcohol and drug abstinence; abstinence was confirmed at both study visits using a breathalyzer, urine drug screen and urine ethyl glucuronide (EtG). The sample reported here is the same as a previously reported study of structural connectivity (Flook et al., 2021). Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study and written informed consent was obtained after providing participants with a complete description of the study.

Alcohol and anxiety measures

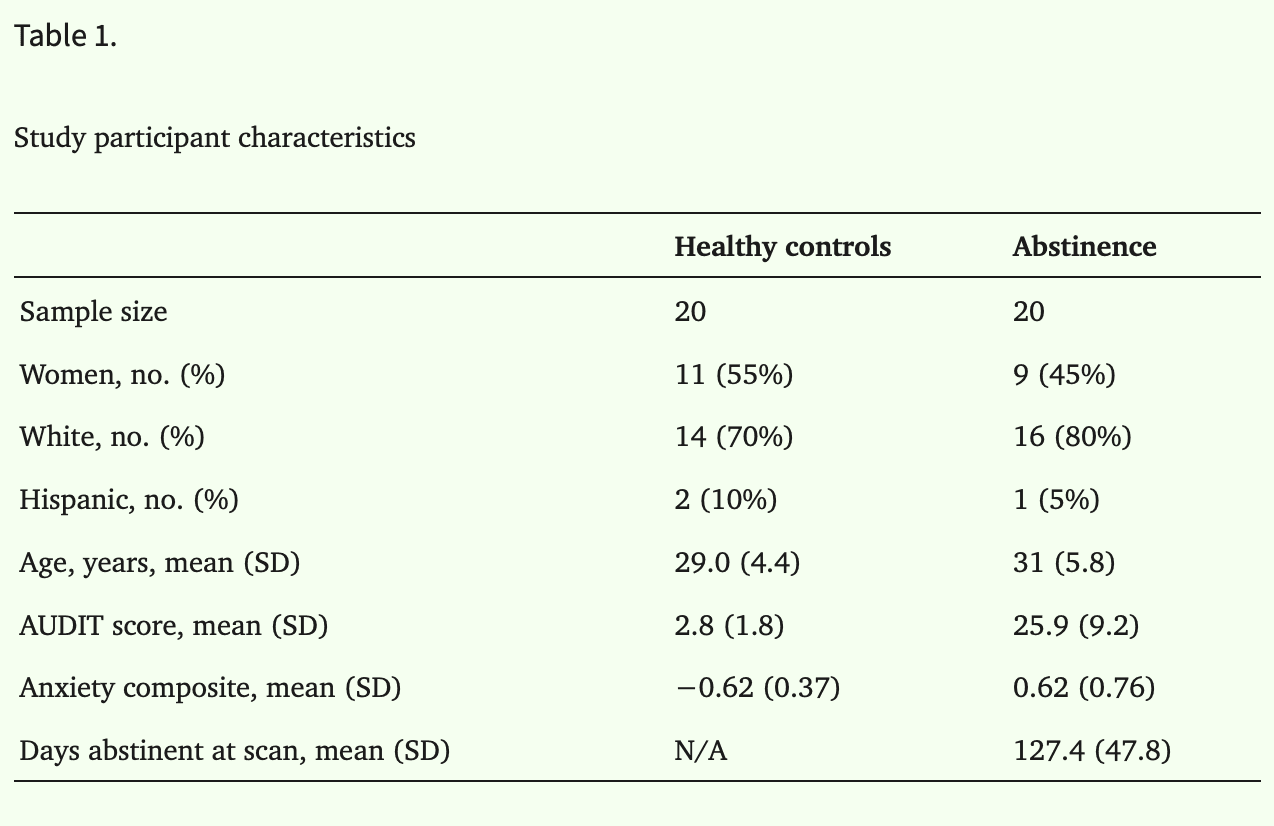

Alcohol use was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 1989; see Table 1), a 10-item self-report of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related behaviors and consequences.

To provide a comprehensive assessment of anxiety, participants completed several self-report measures (see Table 1). The anxiety measures included the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1983), Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation (Leary, 1983), Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck et al., 1988), Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (Carleton et al., 2007), Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (Liebowitz, 1987) and Penn State Worry Questionnaire (Meyer et al., 1990). The anxiety measures were moderately correlated for both groups (average r = 0.50); therefore, a composite anxiety score was created by averaging standardized scores (M = 0, SD = 1) for each questionnaire. Of note, the arithmetic mean was nearly identical (r = 0.99) to a composite score based on a principal factor analysis.

Data acquisition

Functional MRI data was collected on a 3T scanner with a 32-channel head coil. The scanning sequence was selected to optimize subcortical regions: 2 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm slices, 2 s TR, 25 ms TE and −15° angle. Anatomical information was acquired with a standard T1-weighted image. Seven minutes of resting state fMRI (rsfMRI) data were collected. During data collection, participants were instructed to lie still, look at a fixation cross, and not fall asleep. Although the gold standard length of rsfMRI is changing with current guidelines recommending 10 minutes, prior evidence suggests that 7–8 minutes of resting state is sufficient for a reliable estimate of connectivity. For example, Birn et al. (2013) found that improvements in reliability across sessions plateaued around 7–8 minutes providing evidence that reliable estimates of networks observed over multiple sessions are provided by 7–8 minutes of data. While longer rsfMRI scan length is associated with better reliability (Van Dijk et al., 2009; Birn et al., 2013; Gordon et al., 2017; Tozzi et al., 2020), a majority of these studies report significant differences between scan lengths ≤10 minutes and long scan lengths ≥20 minutes, and differences between 7 and 10 minutes are reported to be negligible (Birn et al., 2013). Furthermore, our approach of constraining analyses to a single seed region and extracting connectivity values from a small network based on established structural and functional connectivity patterns across species, minimizes reliability concerns related to atlas selection and thresholding (Tozzi et al., 2020).

Data processing

Intrinsic functional connectivity was estimated using the CONN toolbox (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012) implemented in SPM12 MATLAB (version R2018a). Pre-processing and connectivity analyses were performed using the default pipeline in CONN. Specifically, blood oxygenated level dependent (BOLD) signal was preprocessed using motion estimation, slice timing correction, outlier detection and scrubbing to remove the influence of outlier scans. To remove potential sources of noise, signal was motion corrected and band pass filtered (0.01–0.1 Hz), and white matter, global, and CSF signals were removed using the CONN toolbox denoising option Compcorr (Behzadi et al., 2007). Outlier scans were detected using framewise displacement (>0.9 mm) and global signal change (±5 std) and applied as a confound to the denoising process. The mean framewise displacement did not differ between groups (t(38) = 0.32, P = 0.75), and no subjects had a mean framewise displacement >0.40.

Regions of interest

Regions of interest were selected from prior animal and human data of BNST structural and functional connectivity. The BNST was anatomically defined using a previously published mask (Avery et al., 2014). The Harvard–Oxford atlas templates were used for the amygdala and hippocampus (50% probability threshold); the hippocampus was manually segmented into the anterior hippocampus using the uncus as the boundary. For the anterior insula, a mask developed by Farb et al. (2013) was selected that has previously been used to demonstrate anterior insula structural connectivity with the BNST (Flook et al., 2020). The hypothalamus mask was created based on the Mai atlas by JUB using methods similar to those for the BNST (Avery et al., 2014). The hypothalamus mask has been used previously (Flook et al., 2021) and includes all subregions; the right hypothalamus is 62 voxels [center of gravity: x = 2.76, y = −6.74, z = −14.8], and the left hypothalamus is 41 voxels [center of gravity: x = −3.46, y = −6.37, z = −14.8]. Finally, the vmPFC mask was defined based on a 10-mm sphere surrounding the peak point of vmPFC-BNST connectivity from our previous study [x = 0, y = 43, z = −9] (Avery et al., 2014). All region masks were manually inspected for each individual to confirm anatomical accuracy and to ensure that no ROIs overlapped.

Intrinsic Functional Connectivity Analysis: Correlations of the time series were estimated between the average time courses for the BNST seed region with each of the regions of the BNST network, producing connectivity averages for each BNST network region. These region connectivity values were used for all subsequent analyses.

Statistical analysis

Group analysis

A linear mixed model was used to test the hypothesis that BNST intrinsic functional connectivity differs for the abstinence group compared to controls. The linear mixed model included region (amygdala, anterior hippocampus, anterior insula, hypothalamus, vmPFC), group (abstinence/control), and sex (male/female) as fixed factors (along with the two and three-way interaction terms) and participant as a random factor. Hemispheres of the BNST and ROIs were included as control variables, as hemispheric differences in connectivity have been shown in previous studies (Ray et al., 2010; Baur et al., 2013; Moran-Santa Maria et al., 2015; Gorka et al., 2017; Onay et al., 2017). The omnibus test, with region as a factor, provided control for Type I error. Analyses were performed using lme4 (Bates et al., 2015) package in R studio (R Core Team, 2017). Post hoc analyses were conducted for all significant effects and interactions using the lme4 and emmeans packages (Bates et al., 2015; Lenth, 2019), which correct for multiple correction using the Tukey method. Statistical significance was determined by α < 0.05. To ensure that length of abstinence did not impact results, a linear mixed model was conducted to demonstrate that individual differences in connectivity were not associated with length of abstinence (all P’s > 0.10). Effect sizes were reported with partial eta squared and Cohen’s d.

Abstinence group analysis of individual differences

Within the abstinence group, linear mixed models were used to test the effect of anxiety and alcohol use severity on BNST network intrinsic functional connectivity (α < 0.05). The linear mixed model included region (amygdala, anterior hippocampus, anterior insula, hypothalamus, vmPFC), abstinence symptoms (anxiety or alcohol use severity) and sex (male/female) as fixed factors (along with the two and three-way interaction terms) and participant as a random factor. Hemispheres of the BNST and ROI were included as control variables. Post hoc analyses were conducted for all significant effects and interactions using the emmeans package. Effect sizes were reported with partial eta squared and Cohen’s d.

RESULTS

Participants

The groups did not differ by age (P = 0.23), sex (P = 0.63), or race/ethnicity (white vs. non-white, P = 0.33, see Table 1 for all characteristics). Self-reported sex assigned at birth matched gender identity of all participants. The abstinence group had greater AUDIT (t = 10.99, P < 0.001) and anxiety (t = 6.56, P < 0.001) scores compared to the control group.

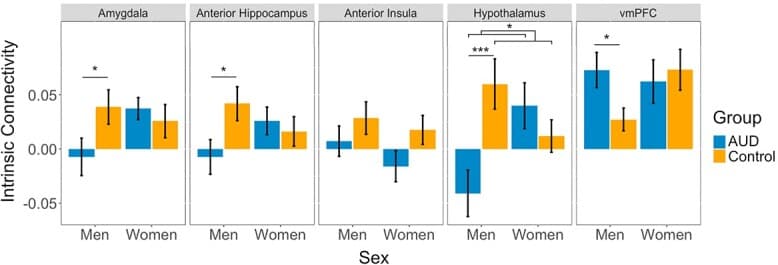

BNST functional connectivity group differences in abstinence

To test for group differences in BNST intrinsic functional connectivity, we conducted a linear mixed model with group, region, sex and all interactions as factors. The findings showed a main effect of region (F(4, 742) = 12.89, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.06), a significant group × region interaction (F(4, 742) = 3.64, P = 0.01, η2 = 0.02), and a significant group × region × sex interaction (F(4, 742) = 11.50, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.06; Fig. 2). Post hoc analysis by region demonstrated significant sex × group interactions for the hypothalamus (t = 4.47, P < 0.001, d = 0.85), anterior hippocampus (t = 2.05, P = 0.04, d = 0.39), amygdala (t = 2.00, P = 0.048, d = 0.38) and vmPFC (t = 2.03, P = 0.04, d = 0.39) but not the anterior insula (t = 0.42, P = 0.67, d = 0.08). Further investigation of the significant sex × group interactions within each region showed significant group effects for men but not for women for each of the regions. In men, the abstinent group had lesser BNST functional connectivity than the control group with the amygdala (t = 2.26, P = 0.03, d = 0.43), the anterior hippocampus (t = 2.41, P = 0.02, d = 0.46) and the hypothalamus (t = 4.95, P < 0.001, d = 0.94). The opposite pattern was seen in the vmPFC, with men showing greater BNST functional connectivity in the abstinent group (t = 2.27, P = 0.03, d = 0.43). There were no group differences in women for any region (all P’s > 0.05). There were no main effects of group (F(1,36) = 2.40, P = 0.13, η2 = 0.06) or sex (F(1,36) = 0.46, P = 0.50, η2 = 0.01) and no significant interactions of group × sex (F(1,36) = 2.61, P = 0.12, η2 = 0.07) or region × sex (F(4,742) = 1.91, P = 0.11, η2 = 0.01).

Individual differences in BNST intrinsic functional connectivity during abstinence

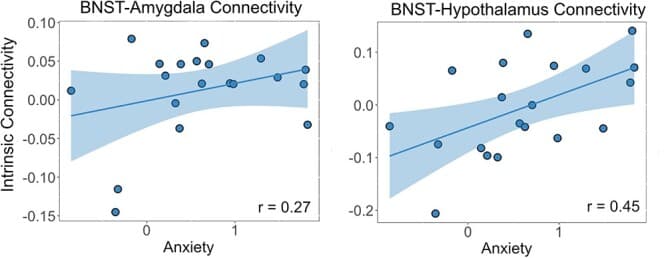

To determine whether individual differences in anxiety or alcohol use severity were associated with BNST intrinsic functional connectivity, we conducted linear mixed model analyses in the abstinent group. For the anxiety model there was a significant anxiety × region interaction (F(4, 362) = 3.77, P = 0.005, η2 = 0.04). Post hoc analysis revealed positive correlations between anxiety and BNST-hypothalamus connectivity (r = 0.45, P < 0.001, d = 1.01) and BNST-amygdala connectivity (r = 0.24, P = 0.03, d = 0.50; see Fig. 3). No other regions had significant correlations. There were no significant main effects or other interactions: anxiety (F(1, 16) = 0.50, P = 0.49, η2 = 0.03), anxiety × sex (F(1, 16) = 0.02, P = 0.89, η2 = 0.00), or anxiety × region × sex (F(4, 362) = 0.92, P = 0.45, η2 = 0.01).

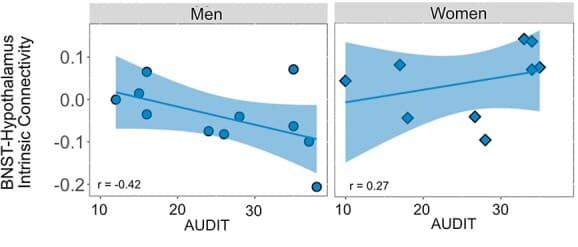

For the alcohol use severity model, there was a significant interaction of severity × region × sex (F(4,362) = 5.90, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.06). Post hoc analysis of the three-way interaction by region demonstrated a significant severity × sex interaction with BNST-hypothalamus connectivity (t = 3.06, P = 0.004, d = 0.91): men had a negative relationship between alcohol use severity and BNST-hypothalamus functional connectivity (r = −0.42, P = 0.005, d = 1.23) and women had a non-significant positive relationship (r = 0.27, P = 0.11, d = 0.56, Fig. 4). There were no significant severity × sex interactions for BNST connectivity with the amygdala (t = 1.76, P = 0.08, d = 0.52), anterior hippocampus (t = 1.71, P = 0.10, d = 0.51), anterior insula (t = 0.17, P = 0.87, d = 0.05) or vmPFC (t = 1.31, P = 0.20, d = 0.39). There was no main effect of severity (F(1, 16) = 0.39, P = 0.54, η2 = 0.02), severity × region interaction (F(4,362) = 0.27, P = 0.89, η2 = 0.00), or severity × sex interaction (F(1,16) = 1.72, P = 0.21, η2 = 0.10).

DISCUSSION

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to investigate whether there are BNST intrinsic functional connectivity differences in individuals during early abstinence compared to controls and represents a critical step in translating findings from animal models to humans. One of the main findings of this study was alterations in BNST-hypothalamus connectivity, with both significant group differences in BNST-hypothalamus connectivity and individual differences with alcohol use severity and anxiety in the abstinent group. A second key finding was sex differences in BNST intrinsic functional connectivity with other brain regions for both the group analysis and individual differences with alcohol use severity. Finally, BNST intrinsic functional connectivity was associated with individual differences in alcohol use severity and anxiety in the abstinent group.

The BNST-hypothalamus pathway emerged as one of the key connections that differed in abstinence from AUD. The projections from the BNST to the hypothalamus have been investigated in rodents and shown to regulate autonomic and neuroendocrine function, including the release of stress hormones that activate the stress response (Crestani et al., 2013; Dabrowska et al., 2016). There were three main BNST-hypothalamus connectivity findings. First, abstinent individuals had lesser intrinsic connectivity between the BNST and hypothalamus relative to controls, especially in men. Second, in abstinent individuals, greater BNST-hypothalamus connectivity was associated with higher anxiety levels. Third, in abstinent men, greater BNST-hypothalamus connectivity was associated with higher alcohol use severity. Overall, these results suggest that this critical, stress-related pathway is altered in abstinence and is associated with common abstinence symptoms. Despite lesser BNST-hypothalamus connectivity in the abstinent group compared to controls overall, abstinent men had positive associations between BNST-hypothalamus connectivity and both anxiety and alcohol use severity. This pattern of findings may indicate a disruption of the much of the pathway’s baseline functioning but continued use for stress-related signaling. To our knowledge, no other studies have investigated intrinsic functional connectivity between the BNST and hypothalamus during abstinence. However, our lab investigated BNST structural connectivity during abstinence in this sample (Flook et al., 2021) and found evidence for altered BNST-hypothalamus structural connectivity. For structural connectivity, BNST-hypothalamus connectivity was greater in abstinent women compared to controls, with no differences in men (Flook et al., 2021). Thus, the findings from the structural and functional connectivity approaches suggest that the BNST-hypothalamus pathway differs during abstinence in ways that are sex specific. Future studies of sex differences in BNST intrinsic functional connectivity will be critical for improving our understanding of sex differences in alcohol use and abstinence.

The majority of BNST connectivity differences were observed specifically in men. In this study, abstinent men, relative to control men, had lesser BNST connectivity with the amygdala, anterior hippocampus and hypothalamus and greater connectivity with the vmPFC. The BNST, amygdala, anterior hippocampus and hypothalamus serve to generate and propagate stress responses and anxiety-related behaviors (Robinson et al., 2019; Fischer, 2021). Lesser connectivity in these BNST pathways could reflect less robust stress-signaling during abstinence for men, which would have important ramifications for understanding stress-related relapse. The vmPFC, which showed the opposite relationship, is an important regulatory region that mediates the stress response and anxiety-related behaviors (Motzkin et al., 2015). Increased vmPFC connectivity could indicate increased recruitment of regulatory inputs to the BNST during abstinence. It is possible that stronger recruitment of regulatory regions is needed to maintain abstinence, or that individuals with greater regulatory inputs to stress circuits are more successful at maintaining abstinence. The specific findings in men are intriguing, given known sex differences in which women are more likely to relapse in response to stress than men (Erol and Karpyak, 2015). The current study’s findings could reveal the reason behind the sex difference in triggers for relapse: abstinent men have decreased BNST connectivity with stress-related regions and increased connectivity with regulatory regions, which may lead to a reduced likelihood of relapse due to stress. Perhaps targeting these connections could decrease risk of stress-related relapse in abstinent women.

Individual differences in anxiety and alcohol use severity were associated with BNST intrinsic functional connectivity. Abstinent individuals with higher anxiety also had greater intrinsic functional connectivity between the BNST and both the amygdala and hypothalamus. The BNST, hypothalamus and amygdala have previously been associated with anxiety in rodent and human studies (for reviews see Ressler, 2010; Avery et al., 2016; Fischer, 2021). Increasing evidence has emerged for the importance of BNST-amygdala connectivity in anxiety, though primarily in fMRI studies that induce an anxious state. In intrinsic functional connectivity studies, BNST-amygdala connectivity has been described a number of times (for example see Avery et al., 2014; Gorka et al., 2017; Tillman et al., 2018), though less is known about the association between intrinsic connectivity and anxiety. One study demonstrated greater intrinsic BNST-amygdala functional connectivity was associated with increased behavioral response to negative stimuli (Pedersen et al., 2020). However, multiple studies of trait anxiety have not consistently reported differences in BNST-amygdala intrinsic functional connectivity (Pedersen et al., 2020; Berry et al., 2021), suggesting that the present findings might be specific to alcohol use disorder and abstinence. As differences in BNST-amygdala connectivity are more associated with anxiety-inducing tasks than rest, it is possible that being at rest for abstinent individuals is a similar state to an anxiety-inducing task and could explain the elevated anxiety symptoms in abstinence. In addition to associations with anxiety, abstinent men with higher alcohol use severity had greater BNST-hypothalamus intrinsic functional connectivity. As reviewed earlier, BNST projections to the hypothalamus regulate the HPA axis stress response (for more details see the review by Crestani et al., 2013), thus BNST-hypothalamus intrinsic functional connectivity may reflect altered, possibly increased, stress pathways. Alternatively, greater BNST-hypothalamus connectivity could indicate that greater input from the BNST is required to maintain homeostasis of the HPA, which is consistent with stress literature in which stress regions are dysregulated following prolonged periods of stress (for a recent review, see Kirsch and Lippard, 2022). Interestingly, recent work demonstrated that the BNST-hypothalamus pathway is negatively associated with affective symptoms (Banihashemi et al., 2022), reinforcing the hypothesis that the BNST-hypothalamus pathway is involved in regulating affective symptoms and might be appropriately greater in abstinence to prevent relapse. Since the alcohol use severity measure was based on pre-abstinence drinking, another possible explanation is that the intrinsic BNST-hypothalamus connection takes longer to normalize in individuals who were heavier drinkers.

This study had some limitations. The first limitation is that this initial study had a modest sample size. While several investigations of BNST connectivity have used large, publicly available data sets, to our knowledge, the available datasets do not include the comprehensive characterizations of abstinence, anxiety, and depression required to test the translation of rodent findings in AUD. Thus, the sample collected for this study is unique and fills a critical gap in our understanding of abstinence. Second, we used a targeted region of interest approach to investigate BNST connectivity in brain regions known to have strong structural and functional connections across species. While this decision provided a hypothesis-based approach that maximized statistical power, a limitation is that we did not investigate BNST connectivity in other brain regions. Therefore, a study powered for whole-brain analysis is an important next step. In addition, many of the brain regions investigated in this study are relatively small. While we used well-established methods for investigating small regions, there could be benefit from conducting this study using ultra-high resolution imaging such as 7T MRI. Lastly, the within sex sample sizes were relatively small; therefore, the sex differences findings should be replicated using a larger sample.

The results of this study prompt important future directions. One interesting avenue of future studies will be to replicate the sex differences and explore potential mechanisms underlying sex differences. For example: are the sex differences observed during alcohol use or do they emerge in abstinence? Do the sex differences fluctuate with levels of sex hormones? Another important future direction is to investigate heterogeneity within abstinence. In this study, we investigated alcohol severity as a pre-abstinence individual difference and anxiety as an abstinence-related individual difference. Large samples will provide the statistical power needed to investigate other sources of heterogeneity including family history, trauma, other drug use, age of drinking onset and duration of AUD. Further, the study population endorsed complete abstinence but future studies could compare brain activity in individuals with complete abstinence vs decrease in drinking behavior and examine for a dose–response to degree of decreased alcohol intake. It will also be important to complement these intrinsic functional connectivity findings with task-based functional connectivity studies that probe how the BNST network responds to stressors during abstinence. In addition to employing different methods for investigating this connectivity, next steps should also include expanding on the results of the study in rodent models. Multiple neurotransmitters are involved in communication between the BNST and hypothalamus, and both excitatory and inhibitory connections have been described (for review see Crestani et al., 2013). For example, adrenergic signaling in the BNST is also critical for stress-induced reinstatement, as both β1- and β2-adrengergic receptor antagonists and α1-adrenergic receptor agonists have been shown to block stress-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviors in rodents (Erb et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Leri et al., 2002; Vranjkovic et al., 2014). It is likely that the BNST-hypothalamus findings of the current study reflect complex differences in communication spanning multiple neurotransmitter systems that are not currently discernible with fMRI technology. Likewise, rodent studies could help evaluate the possibility of a third region that is co-regulating the BNST and hypothalamus as has been proposed previously (Banihashemi and Rinaman, 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2018). Finally, rodent studies have demonstrated a role for the BNST in relapse. Future studies examining whether BNST intrinsic functional connectivity can predict relapse is a critical next step for the development of treatments that target relapse prevention.