Abstract

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) cause a range of physical harms, but the major cause of alcohol-related mortality is alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), in some countries accounting for almost 90% of alcohol-related deaths. The risk of ALD has an exponential relationship with increasing alcohol consumption, but is also associated with genetic factors, other life-style factors and social deprivation. ALD includes a spectrum of progressive pathology, from liver steatosis to fibrosis and liver cirrhosis. There are no specific treatments for liver cirrhosis, but abstinence from alcohol is key to limit progression of the disease. Over time, cirrhosis can progress (often silently) to decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Liver transplantation may be suitable for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and may also be used as a curative intervention for HCC, but only for a few selected patients, and complete abstinence is a prerequisite. Patients with AUD are also at risk of developing alcoholic hepatitis, which has a high mortality and limited evidence for effective therapies. There is a strong evidence base for the effectiveness of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for AUD, but very few of these have been trialled in patients with comorbid ALD. Integrated specialist alcohol and hepatology collaborations are required to develop interventions and pathways for patients with ALD and ongoing AUD.

Introduction

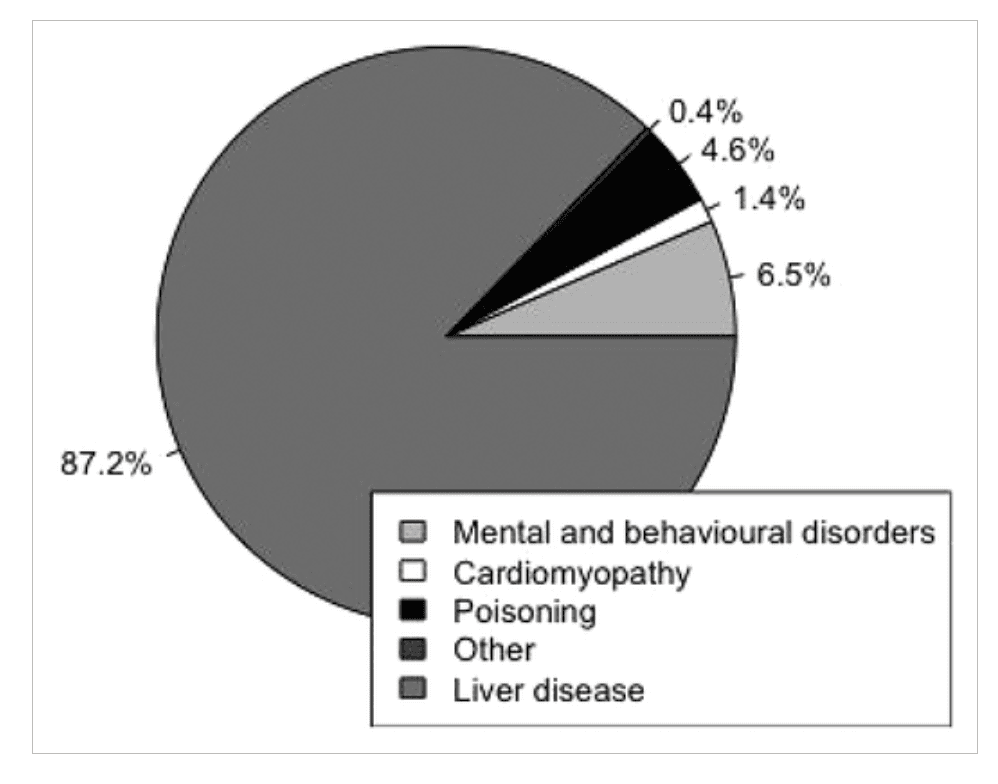

The World Health Organization estimate that harmful alcohol consumption is the seventh leading cause of global death and disability [1]. Alcohol causes a wide spectrum of pathology, but alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) causes a significant proportion of the attributable morbidity and mortality [1]. This proportion varies geographically and is generally highest in middle-aged males. In some areas, such as the United Kingdom, almost 90% of alcohol-related deaths are caused by ALD (Fig. 1) [1, 2].

Figure 1

The relative proportion of alcohol-related deaths attributed to different pathologies as recorded by ICD-10 code classification for the United Kingdom in 2016. Liver disease accounts for almost 90% of alcohol-related deaths (analysis of data from the archives of the Office of National Statistics, Ryan Buchanan [2])

Until the 1970s the association between alcohol and liver cirrhosis had been noted, but doubt about a causal relationship persisted. Uncertainty gained traction because not all people with alcohol use disorder (AUD) developed cirrhosis, but it was often observed when malnutrition was also present. This led to debate concerning whether it was malnutrition rather than alcohol that was the primary risk factor for liver cirrhosis. However, a team working in New York settled the argument. Leiber et al. fed ethanol to 15 baboons as part of an otherwise balanced nutritious diet. The team observed the whole spectrum of alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) and glimpsed the underlying pathogenic pathway [3].

Since the 1970s, alcohol has become more available and the incidence of ALD has increased. This review summarizes the latest epidemiology of ALD and gives an overview of the spectrum of attributable liver pathology. It also synthesizes the evidence for best practice in clinical hepatology and addiction psychiatry to understand and manage this complex comorbid condition.

Epidemiology of alcohol-related liver disease

In 2017 liver disease caused more than 1.32 million deaths world-wide. In Europe, North and South America and Central Asia the most common cause of liver cirrhosis is ALD [4]. Countries in the European region consume some of the highest quantities of alcohol [5], with more than 2 million years of life lost to liver disease in people under the age of 50 years, with 60–80% of these attributed to alcohol [6]. In some European countries, notably Finland and the United Kingdom, there has been an increase in ALD-related deaths in recent decades which has been associated with a reduction in the relative price of alcohol and a steep rise in consumption [2, 6].

An overall increase in alcohol consumption has been noted world-wide [5, 7], including in the United States [8], where there has been a significant rise in the prevalence of harmful consumption of alcohol [9], and a corresponding 65% increase in annual liver cirrhosis mortality since 2009. Notably, this increased mortality can be attributed almost entirely to ALD in young people [8].

At an individual level the probability of developing ALD has a close and exponential relationship with levels of alcohol consumption [10-12]. However, risks of ALD are increased with only modestly elevated levels of consumption [12]. ALD has also been associated with a number of genetic polymorphisms [13], and is more likely in people with comorbid obesity or chronic viral hepatitis [14, 15]. Social deprivation is also a significant risk factor, with individuals in the two lowest quintiles of the Index of Multiple Deprivation, and particularly those who are homeless are at greatest risk of liver morbidity and mortality [16-19]. This is thought to be a consequence of the increased affordability of alcohol [6] and the high prevalence of multiple-risk comorbidities in these populations, including hepatitis C, smoking, obesity and a lack of exercise [16]. The combination of alcohol with a range of other factors which cause harm to health may account for the so-called ‘alcohol harm paradox’, where deprived individuals drinking the same quantities of alcohol as more affluent individuals are disproportionately affected with ALD [16].

The spectrum of alcohol-related liver disease

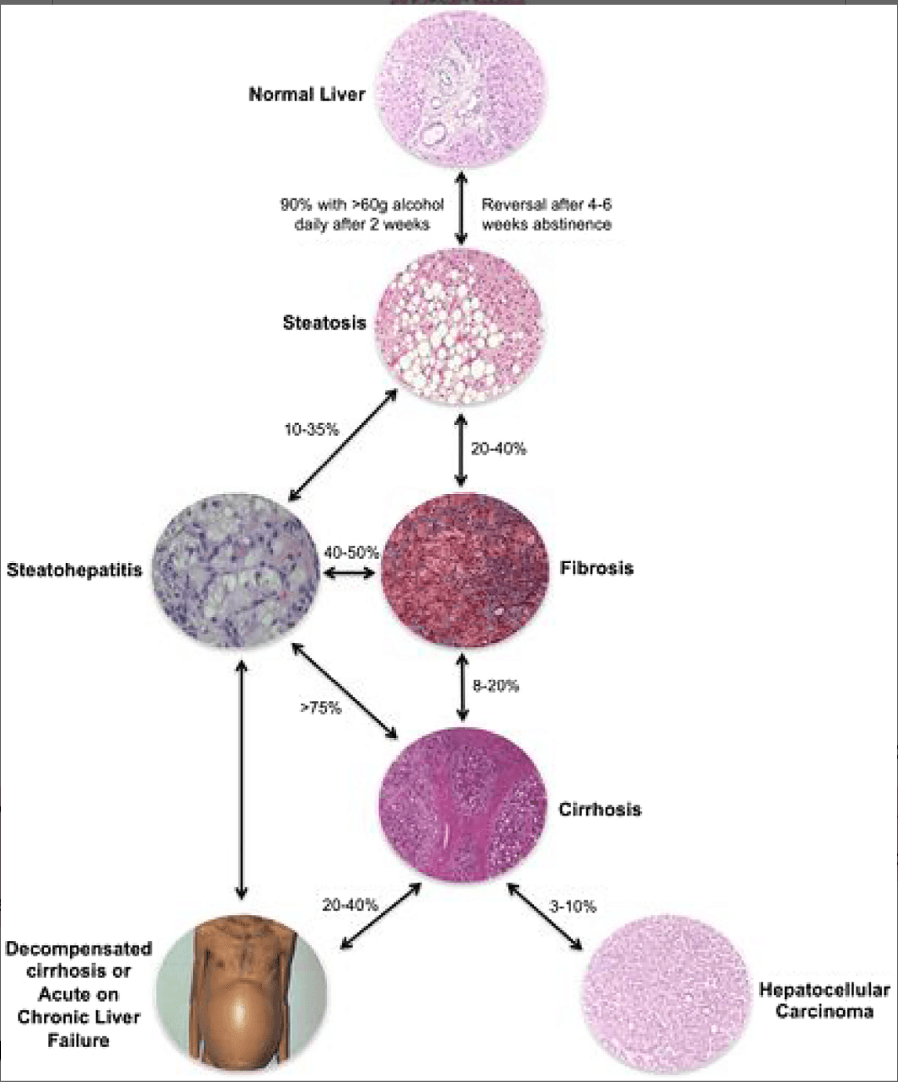

Excessive consumption of alcohol leads to a spectrum of liver disease, including liver steatosis, fibrosis, compensated cirrhosis (CC), decompensated cirrhosis (DC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and alcoholic hepatitis (AH) (see Fig. 2). A ‘fatty liver’ or steatosis is an extremely common finding in people who drink alcohol, and the accumulation of fat in the liver can occur after just a few days of drinking alcohol. The rate of progression of liver disease varies in different subpopulations, but is increased at all stages (steatosis to fibrosis through to DC and HCC) by the consumption of alcohol. Conversely, the rate of progression is reduced by abstinence [20]. AH is a distinct acute disease of the liver that usually occurs in people with AUD who have recently consumed large quantities of alcohol. It typically, but not exclusively, occurs in people with underlying liver cirrhosis (see Fig. 2) [21].

Figure 2

An overview of the spectrum of alcohol-related liver disease. Images courtesy of Dr M. Isabel Fiel (Fig. 1 from Crabb et al. [36], reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Overview of hepatic metabolism of alcohol

Hepatocytes make up 70% of the liver mass and play the central role in alcohol metabolism. Within each cell there are three enzymic pathways for the metabolism of alcohol. The major pathway occurs in the cytoplasm of the hepatocytes. In this pathway ingested alcohol is oxidized by alcohol dehydrogenase to acetaldehyde. In a second pathway—the major inducible pathway—alcohol is oxidized to acetaldehyde in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum by the cytochrome p450 2EI enzyme. In the third, more minor inducible pathway, alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde via a catalase enzyme. The acetaldehyde produced by all three pathways is toxic to the cell, so it is rapidly transported to the mitochondria where it is converted to acetate via an acetaldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme. The acetate then passes into the circulation to play a role in metabolism elsewhere.

How does alcohol damage the liver?

The mechanisms by which alcohol directly harms the liver sufficiently to cause chronic liver disease are complex. Excessive alcohol consumption increases the production of enzymes necessary for its metabolism. This leads to increased levels of acetaldehyde and harmful pro-oxidants, which are directly cytotoxic to hepatocytes. As a natural response to tissue injury, fibrogenesis occurs to isolate and limit damage to a specific area of tissue. Fibrogenesis occurs because the liver injury activates hepatic stellate cells, which form extracellular matrix proteins and release inflammatory proteins that lead to a cycle of further activation, protein deposition and fibrogenesis. Cirrhosis is an advanced form of fibrosis where the normal liver micro- and macro-structure has been lost and is characterized by the development of regenerative nodules divided by fibrous septa. Liver cirrhosis is considered to be a pre-malignant condition. The processes leading to liver cirrhosis including tissue injury and repair, alongside directly mutagenic properties of the acetaldehyde and harmful pro-oxidants, create an environment prone to develop HCC.

The underlying causes of AH and the intense inflammatory infiltration of the liver that characterizes the condition are not completely understood. It is probable that a complex interplay of factors is involved. There is evidence that alcohol increases gut permeability, which leads to high levels of bacterial toxins (e.g. lipopolysaccharide endotoxin) passing from the gut into the circulation. In AH it is postulated that these activate inflammatory responses within the liver. Additionally, alcohol directly activates innate liver immune cells (called Küpffer cells) and sensitizes hepatocytes to some of the inflammatory proteins they produce leading to cell death. Hepatocyte death itself activates the inflammatory cascade, leading to further cell death, and in this way the pathogenesis of AH is sustained.

Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis

Clinical manifestations

Opportunities to screen for liver disease in patients with harmful alcohol consumption are often missed, and many patients only present to health services once symptoms relating to DC have occurred [22, 23]. As indicated in Fig. 2, cirrhosis can progress from CC to DC at a rate of 5–7% per year [24]. As well as alcohol consumption, a range of factors, including infection, medications such as benzodiazepines, surgical operations such as heart valve replacements and gastrointestinal bleeding can trigger progression to DC. DC is characterized by the development of ascites (free fluid within the abdominal cavity), abnormal clotting, jaundice (yellow discolouration of the skin and sclera) and encephalopathy (resulting in confusion, drowsiness and coma).

Assessment

As alcohol-related liver fibrosis and CC develops silently over many years, the challenge is to make an early initial diagnosis. Accordingly, numerous targeted screening approaches have been developed in people who drink alcohol at high levels to try to identify disease at an earlier stage. According to European guidelines, targeted screening is appropriate in men drinking >30 g/day and women drinking >20 g/day of ethanol, but should also be considered in those presenting with other physical manifestations of AUD, such as cardiomyopathy and peripheral neuropathy [25].

Standard liver function tests including raised blood levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase are poor markers of ALD, and should only be considered in conjunction with a specific test for liver fibrogenesis [26]. A range of biochemical fibrosis markers are recommended for this assessment, including the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test, fibrosis 4 (Fib4) test and FibroTest [25]. However, in the United Kingdom the current clinical guidelines on the management of cirrhosis recommend that patients with AUD be referred directly for transient elastography (TE) [27]. In TE a shear wave is transmitted through the liver and this gives a measure of liver stiffness in kilopascals (kpa). Liver stiffness correlates with the degree of liver fibrosis, and TE is therefore a useful non-invasive assessment for liver cirrhosis and advanced fibrosis [28]. In cases of diagnostic uncertainty, or to more accurately stage the degree of liver fibrosis, a liver biopsy is still appropriate in some cases. However, the additional diagnostic and prognostic information from a liver biopsy needs to be weighed against potential serious complications which occur following <2% of procedures [25, 27]. Patients with DC usually present to health-care services with acute illness, and the diagnosis is apparent from clinical examination of the patient for hepatic encephalopathy, ascites and jaundice.

Treatment

There are no licensed pharmacological treatments to reverse ALD. Management is therefore focused upon monitoring for complications of cirrhosis, abstinence and other life-style modifications, such as weight loss and dietary modification—there is observational evidence that coffee reduces progression to cirrhosis [29]. For a small minority of patients with end-stage disease, liver transplantation (LT) may be required.

Patients with established liver cirrhosis should be monitored with ultrasonography for the development of HCC and with regular blood tests to assess their degree of liver function, including the ability to synthesize proteins that are essential for the normal functioning of the body. Consideration should also be given to a screening endoscopic examination for oesophageal varices (swollen veins in the oesophagus, due to congestion of the portal vein), which are at risk of rupture.

Abstinence from alcohol is key to preventing disease progression in patients with liver fibrosis and CC [30]. Indeed, even at an advanced stage, inflammation and fibrosis remain reversible on cessation of a, and liver steatosis is considered to be fully reversible with appropriate life-style modifications [20]. Since the 1960s it has been observed that abstinence from alcohol is also key for preventing death in patients with decompensated ALD [31]. This is supported by recent prospective [32] and retrospective cohort studies [33].

All interventions for alcohol use disorders are underpinned by a psychosocial framework [34]. Although the evidence base for psychosocial treatment in patients in ALD is limited [30], a systematic review of treatment trials in ALD found that integrating specialist AUD treatment within hepatology services resulted in higher abstinent rates than referral to a separate treatment service [35]. Recent international ALD treatment guidance now recommends that to engage patients in harm reduction, or ideally achieve abstinence, appropriate psychosocial support services should be available within hepatology centres as part of an integrated multidisciplinary team [25, 36].

Pharmacological treatment in patients with moderate to severe alcohol dependence may also be required for medically assisted alcohol withdrawal, or relapse prevention, especially given the many years of untreated AUD prior to presentation, and the need for long-term sustained abstinence. In terms of alcohol withdrawal, standard practice is variable but there is good evidence for the efficacy of benzodiazepines and carbamazepine for medically assisted withdrawal from alcohol, and preventing further complications such as delirium and seizures [34]. For patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis, and impaired synthetic function, carbamazepine is not recommended and doses of benzodiazepine medication should be reduced, with frequent objective monitoring of symptoms [37]. In clinical practice, oxazepam or lorazepam, which have reduced hepatic metabolism are sometimes used [37]. Given the poor nutritional status of many patients with ARLD, a high index of suspicion needs to be maintained for the development of Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome and all patients in alcohol withdrawal should be treated with parenteral thiamine (usually in combination with other B vitamins) for 3–5 days until no symptoms (confusion, ataxia, opthalmoplegia) remain or treatment continued until no further improvement in symptoms found [34].

Relapse prevention medication may also be considered (Table 1). Acamprosate, naltrexone, nalmefene and disulfiram are all approved in one or more region for the treatment of alcohol dependence [38]. Baclofen has been recently approved for AUD treatment in France only for patients who have not responded to other treatments [39].

Table 1. Relapse prevention medications in patients with AUD and ALD (adapted from AASLD [36].

![Table 1 Relapse prevention medications in patients with AUD and ALD (adapted from AASLD [36]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2F9ge8ptsf9tdf%2F1mstmZBYQ6ABE30YwYU5J2%2F7728794d3d0a226aa9cba43d5ab6ed6d%2FTable_1_Relapse_prevention_medications_in_patients_with_AUD_and_ALD__adapted_from_AASLD_-36-.png&w=3840&q=75)

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, causing accumulation of acetaldehyde following alcohol consumption, which can have potentially severe adverse effects and so should be used with caution, and only after a thorough assessment in patients with ALD [34]. There are also concerns about potential hepatotoxic effects of naltrexone [36] with five to 10-fold increases in naltrexone plasma concentrations reported in patients with cirrhosis [38, 40]. However, data suggest that high doses (up to 300 mg daily), concurrent use of non-steroidal analgesics and obesity may account for the raised transaminases seen in early studies, and Phase 2 studies showed no evidence of toxicity at doses of 800 mg daily for 1 week. Nalmefene, another opioid system modulator, structurally similar to naltrexone, is extensively metabolized by the liver, largely by glucuronidation, and has not been identified to have a risk of hepatotoxicity, although one small study of patients with liver disease showed significantly reduced clearance of nalmefene inversely proportional to the level of hepatic pathology. Its efficacy has not been specifically investigated in patients with ALD [38].

Acamprosate is derived from homotaurine, a non-specific gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist and calcium. It is not metabolized by the liver and has no impact on drugs subject to hepatic metabolism or which have an impact upon the CP450 system. It is excreted via the kidneys, although there are no trials specifically assessing its effects in patients with ALD, Acamprosate should be considered as a treatment option in this patient group [38]. Only baclofen, a GABA-B receptor agonist, has been assessed in patients with established cirrhosis. In a single randomized controlled trial (RCT), patients who received baclofen were twice as likely to report abstinence than patients receiving placebo and no hepatotoxic effects were recorded [41]. Importantly, this study demonstrated the safety of baclofen in patients with DC. Conversely, a later RCT showed no benefit from baclofen compared to placebo. However, this trial was conducted in an exclusively male, relatively elderly cohort with hepatitis C and the studies used different outcomes measures, so direct comparison is difficult [42]. In recognition of this uncertainty, but mindful that it is the only relapse prevention medication to be trialled in patients with cirrhosis, an international consensus statement published in 2018 recommended consideration of baclofen to treat AUD in patients with ‘advanced liver disease’ (see Table 1), and this has been supported by recent US guidance [36, 43].

Liver transplantation

Abstinent patients with end-stage ALD or those with a range of extrahepatic manifestations can be considered for LT. ALD is increasingly an indication for LT in the United States [44] and Europe [45]. Since the late 1980s ALD has been considered an appropriate indication for LT, and although early survival rates were poor [46], 5-year post-transplant survival in patients with ALD is now comparable to patients transplanted for other indications and the 1-year post-transplant survival is greater than 80% [44]. However, patients with ALD are at risk from multisystem effects of alcohol including, cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, dementia and malnutrition, and therefore pre-operative assessment needs to be rigorous [47]. Malnutrition is particularly common in patients with ALD [48] and is associated with worse outcomes [49].

Abstinence from alcohol is a prerequisite before a patient is considered for LT, and in many countries a strict 6-month period of abstinence is enforced; however, there is a lack of data supporting such a stringent approach and it is not endorsed by international guidelines. Nevertheless, a careful assessment of risk of relapse is essential. This should involve a multidisciplinary team and include careful exploration of risk factors for relapse, such as a family history of AUD, previous unsuccessful attempts at abstinence and poor social support networks [50, 51].

Prognosis

Patients with CC have a 1-year survival of more than 90% [24]. The likelihood of complications and death in patients with DC correlates closely with scoring systems such as the Child–Turcott–Pugh score or the model for end-stage liver disease score [36]. The Child–Turcott–Pugh score places patients into three classes on the basis of the presence or absence of encephalopathy, jaundice, ascites or coagulopathy [52]. In a systematic review of more than 118 cohort studies, those with the most severe decompensated disease (class C) had a 1-year survival of less than 50% [24].

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Clinical manifestations

ALD is the most common cause of HCC in Europe and North America and accounts for 30% of cases world-wide [53]. For an individual with CC the annual probability of developing HCC is 2.9–5.6% per year, but the incidence is higher in individuals with DC (Fig. 2) [54].

In patients with known ALD, unexplained progression from CC to DC should lead to investigation for a possible HCC. Otherwise, tumour-specific symptoms, including right upper quadrant fullness, weight loss, anorexia or early satiety, are often vague and easily dismissed. Consequently, HCC is often identified during routine surveillance imaging in patients with ALD, or as an incidental finding in patients who have received imaging of their liver for an unrelated indication.

Despite international guidance advocating 6-monthly ultrasound imaging of the liver for patients with ALD, a significant proportion of cases present in patients who have not been effectively engaged with surveillance imaging programmes [54]. Accordingly, patients with ALD present with more advanced cancer and have worse outcomes than patients with HCC due to another underlying cause [55].

Assessment

In patients with established cirrhosis, computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging may be sufficient to establish the diagnosis if pathognomonic features are present. In patients without established cirrhosis or in cases where there is diagnostic uncertainty a biopsy for histology may be necessary, although interval imaging to assess changes in lesion size or character over a short time-period may sometimes be appropriate [56]. The investigation of liver lesions should always be directed by a cancer multidisciplinary service [56].

Treatment

The treatment of HCC in patients with ALD is complex and evolving. In the first instance it is important to establish whether the goal of therapy is palliative or curative. To determine which approach should be taken, a number of patient and tumour-related factors need to be considered. These include whether the patient has CC or DC; whether they would be considered a candidate for LT (i.e. are abstinent from alcohol); and tumour size, number and location within the liver.

Where potentially curative approaches are considered appropriate these may include radio-frequency ablation of the tumour, resection of the tumour or LT. Potential palliative approaches include trans-arterial chemo-embolization, systemic chemotherapy or best supportive care [56].

Prognosis

Prognosis of HCC varies depending on the treatment modality that can be offered. Patients with a small single tumour that is resected have a 5-year survival of 80–90%. In patients who successfully undergo LT, median 5-year survival is as high as 70%; however, where curative therapy cannot be offered, 5-year survival is considerably lower, with those in a terminal stage of disease surviving just a few months [56].

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH)

AH was first clinically defined in 1961 by clinicians working at the Royal Free Hospital in London [57]. It is a distinct clinical syndrome from DC and can occur in patients without established liver cirrhosis [21]. Patients typically present to medical services with jaundice following a recent escalation in alcohol consumption. Serum biochemistry tests show an elevated bilirubin but usually only a modest elevation in ALT. The liver is often enlarged and tender and the patient may complain of nausea, fevers and sometimes vomiting. Histology shows a characteristic inflammatory cell infiltrate alongside other distinctive features.

Assessment

History, examination and blood tests are an important part of the initial assessment to establish the level and duration of alcohol consumption and the clinical and biochemical features of AH. Liver biopsy is not an essential part of the diagnostic pathway but should be undertaken if there is diagnostic uncertainty. Imaging of the liver, usually via ultrasonography, is important to exclude other causes of jaundice and in the presence of fever clinicians should actively exclude infection.

Treatment

To achieve a positive outcome, it is essential that patients diagnosed with AH become completely abstinent. Most cases will be managed in hospital, where they can be monitored for complications and, in severe cases, consideration given to the provision of specific interventions.

In severe cases, corticosteroids are marginally beneficial for short-term survival but convey risks of infection and variceal bleeding, so should only be continued in patients who show a positive initial response [58]. A single trial showed a significant reduction in 1-month mortality by adding a 5-day infusion of N-acetylcysteine to prednisolone, although the reduction in mortality was non-significant in the longer term [59]. Oral or nasogastric tube feeding is also important. Poor nutrition is associated with adverse outcomes in AH [60], and nasogastric feeding has been shown to be comparable to corticosteroid therapy in a single randomized control trial [61], although a later study which combined nasogastric feeding and corticosteroid therapy was not found to be superior to corticosteroid therapy alone [60].

Prognosis

Even with treatment, severe alcoholic hepatitis has a high mortality. In a large UK-based four-arm RCT 28-day mortality rate ranged from 14 - 18%, and 58% of the cohort had died at 12 months [58]. A Spanish study of 142 patients with biopsy-proven AH has shown that abstinence from alcohol was the only factor significantly associated with long-term survival [62].

New developments in treatment of AH

In the absence of any treatment for AH that significantly improves long-term outcomes, trials focusing on hepatic (but not alcohol) treatment are ongoing [63]. LT is now being used in some countries as a therapeutic strategy for selected patients with AH. In 2011 a highly selected case series in France assessed outcomes for patients with AH receiving a liver transplant [64]. The study showed a significant survival benefit compared to matched controls in selected patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis and comparable survival outcomes to patients receiving LTs for other indications. Additionally, subsequent studies have shown that patients receiving a transplant for AH were no more likely to return to drinking than those receiving a transplant after a period of abstinence from alcohol [60]. However, although transplantation for AH now occurs in the United States and parts of Europe it has not become practice in the United Kingdom [65]. Indeed, a recent UK trial investigating the utility of LT in patients with AH failed to recruit any participants [65].

Conclusion

Despite overwhelming evidence of the high levels of morbidity and mortality due to liver disease in patients with AUD, and alcohol-related deaths in patients with liver disease, research and clinical practice aimed at developing a robust evidence base to improve outcomes in this comorbid group remains in its infancy. The paucity of evidence for integrated alcohol treatment in ALD is particularly surprising, given that abstinence improves outcomes at all stages of liver disease, and the evidence base for psychosocial and pharmacological treatment for patients with AUD is well established.

The re-purposing of the drug baclofen has shown some promise in developing collaborations to explore treatments in this comorbid group, but greater integration of both psychosocial and pharmacological treatment pathways across hepatology and addictions is needed before real progress will be made.