Abstract

Introduction: Small-scale clinical studies with psychedelic drugs have shown promising results for the treatment of several mental disorders. Before psychedelics become registered medicines, it is important to know the full range of adverse events (AEs) for making balanced treatment decisions.

Objective: To systematically review the presence of AEs during and after administration of serotonergic psychedelics and 3,4-methyenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in clinical studies.

Methods: We systematically searched PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov for clinical trials with psychedelics since 2000 describing the results of quantitative and qualitative studies.

Results: We included 44 articles (34 quantitative + 10 qualitative), describing treatments with MDMA and serotonergic psychedelics (psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide, and ayahuasca) in 598 unique patients. In many studies, AEs were not systematically assessed. Despite this limitation, treatments seemed to be overall well tolerated. Nausea, headaches, and anxiety were commonly reported acute AEs across diagnoses and compounds. Late AEs included headaches (psilocybin, MDMA), fatigue, low mood, and anxiety (MDMA). One serious AE occurred during MDMA administration (increase in premature ventricular contractions requiring brief hospitalization); no other AEs required medical intervention. Qualitative studies suggested that psychologically challenging experiences may also be therapeutically beneficial. Except for ayahuasca, a large proportion of patients had prior experience with psychedelic drugs before entering studies.

Conclusions: AEs are poorly defined in the context of psychedelic treatments and are probably underreported in the literature due to study design (lack of systematic assessment of AEs) and sample selection. Acute challenging experiences may be therapeutically meaningful, but a better understanding of AEs in the context of psychedelic treatments requires systematic and detailed reporting.

Introduction

Clinical research with psychedelics has provided promising positive results for various mental disorders (Andersen et al., 2020; Bahji et al., 2020; Dos Santos et al., 2018; Vargas et al., 2020). However, sample sizes were generally small and rather selective. With the first phase III randomized clinical trials (RCTs) nearing completion (Mitchell et al., 2021) and many trials currently investigating novel applications (Siegel et al., 2021), some compounds seem close to registration.

The use of psychedelics, particularly in uncontrolled circumstances, is associated with acute adverse events (AEs) such as anxiety, panic, dysphoria, paranoia, and/or dangerous behaviors (Barrett et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2008); such events may contribute to enduring psychological problems (Carbonaro et al., 2016). Although adverse outcomes were mostly described after non-medical psychedelic use, and safety and tolerability have been demonstrated in small clinical trials (Andersen et al., 2020; Dos Santos et al., 2018; Rucker et al., 2018), administration in larger, more heterogeneous patient populations with higher levels of comorbidity may lead to unexpected negative effects. Moreover, adverse drug reactions may lead to non-adherence and discontinuation of treatment (Carvalho et al., 2016), and unresolved and non-integrated difficult experiences may lead to persisting negative outcomes (Grof, 2001; Johnson et al., 2008). It is therefore important to identify the full range of adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs, particularly in vulnerable patients with treatment-resistant mental disorders. The literature on this topic has not been systematically described since 1984 (Strassman, 1984). A 1960 review, based on questionnaires distributed among clinicians representing some 5000 patients (mostly treated with lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)), concluded that AEs were rare, with some exceptions, mostly in patients with schizophrenia, and that these drugs were generally safe when administered with care (Cohen, 1960). A 1984 review of adverse reactions to psychedelics in different settings found that AEs existed on a continuum; from acute, time-limited panic reactions during administration, through transient psychoses lasting several days, to recurrent flashbacks and chronic undifferentiated psychotic and treatment-resistant cases (Strassman, 1984). Flashbacks were later included in the diagnostic category “hallucinogen persisting perception disorder” (HPPD, which appears in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) but not in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10); HPPD is reported occasionally, mostly in the context of frequent non-medical use of serotonergic psychedelics or 3,4-methyenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and may be related with pre-existing psychiatric conditions (Halpern and Pope, 2002; Halpern et al., 2018; Litjens et al., 2014); flashbacks seem to be mostly perceived as mild and neutral to pleasant (Müller et al., 2022). A recent non-systematic, narrative review explored the evidence base for the most frequently mentioned AEs in public discourse, to elucidate which of these harms are based largely on anecdotes versus those that stand up to current scientific scrutiny (Schlag et al., 2022).

Assessing AEs is challenging for multiple reasons; AEs are not always pre-specified, the range of potential reactions can be broad, reporting can be erratic, and terminology is often inconsistent (Golder et al., 2016, 2019) and includes side effects, toxic effects, adverse effects, treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), adverse drug reactions, complications and harms, all of which are used interchangeably (Peryer et al., 2021). This is further complicated by the highly variable and context-dependent subjective effects elicited by psychedelics (Breeksema et al., 2020; Carbonaro et al., 2016).

As more patients with mental disorders will probably be treated with psychedelics in the near future, a complete overview of both therapeutic benefits and AEs is needed for balanced benefit-risk assessments and decisions, and for understanding which patients are most likely (not) to profit (Loke et al., 2007). The current paper aims to systematically review any AEs occurring during or after psychedelic treatments with classic/serotonergic hallucinogens (psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca) and entactogens (MDMA) in patients. Despite relevant pharmacological distinctions, both MDMA and serotonergic hallucinogens are often classified as “psychedelics” and administered under similar therapeutic conditions (Garcia-Romeu et al., 2016; Reiff et al., 2020). AEs of the atypical psychedelics ketamine (Short et al., 2018; Van Amsterdam and Van Den Brink, 2021) and ibogaine (Ona et al., 2022) have recently been reviewed elsewhere.

Methods

Given the relative novelty of this field, this review takes an exploratory—rather than a confirmatory—approach. The review was not preregistered. This systematic review and data synthesis follows a sequential explanatory design, using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (Peryer et al., 2021), Adverse Effects Subgroup framework (Loke et al., 2007), to extract, organize, and synthetize findings from both quantitative and qualitative studies, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). We will use the term AE for any unfavorable or harmful event first occurring during or after the administration of a classic psychedelic or MDMA and irrespective of its relationship with the psychedelic treatment (Loke et al., 2007; Peryer et al., 2021). In this review, acute AEs refer to AEs occurring during or on the day of a psychedelic/MDMA session, whereas late AEs refer to AEs that emerge after the day of the psychedelic/MDMA session. “TEAEs” are sometimes used, defined as an AE that is either not present prior to the treatment or an already present event that has worsened following treatment. As there is no clear distinction between these terms, in this review, we will only distinguish between acute and late AEs.

Selection criteria

All quantitative and qualitative clinical studies describing the treatment of patients with a mental disorder with a classic serotonergic psychedelic (e.g., psilocybin, LSD, mescaline, ayahuasca) or an entactogenic drug (e.g., MDMA, MDA), including open-label studies, case reports or case series, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published since 2000, were included. We excluded systematic reviews, surveys, secondary analyses, and studies with healthy volunteers. We aimed to assess the possible adverse reactions occurring in patients with a diagnosed (mental) disorder who were treated with any of these compounds. As such, we formulated no specific exclusion criteria a priori to allow the broadest inclusion possible and not miss any potential unfavorable outcome.

Search methods

We systematically searched the PubMed/Medline, EMBASE, and PSYCinfo databases on 28 July 2021, combining search strings containing both index1 and free-text terms: one group for psychedelic compounds (e.g., psilocybin OR “lysergic acid diethylamide” OR MDMA) AND another for study type (e.g., “clinical trial” OR qualitative), excluding animal studies. See Supplemental Material 1 for a detailed list of search terms. In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov to cross-check corresponding publications. Systematic searches were complemented by handsearching and checking reference lists.

Quality assessment

A thorough formal quality assessment was not considered pertinent since high-quality, low bias studies may still report poorly on AEs (Loke et al., 2007). We specifically assessed quality criteria relevant in the context of the aim of this review: methods used to monitor or report AEs, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the percentage of participants with prior experience with the drug. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist was used to assess the methodological rigor of qualitative studies (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2020).

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted all descriptive and quantitative information on acute and late AEs, the timing of assessment, and serious AEs (SAEs) from the main text and the supplementary files of the publications. The AE prevalence was recalculated as a percentage of total participants. Qualitative articles were scrutinized for themes and descriptions related to AEs. These were then used to complement, illustrate, and contextualize findings from quantitative studies.

Results

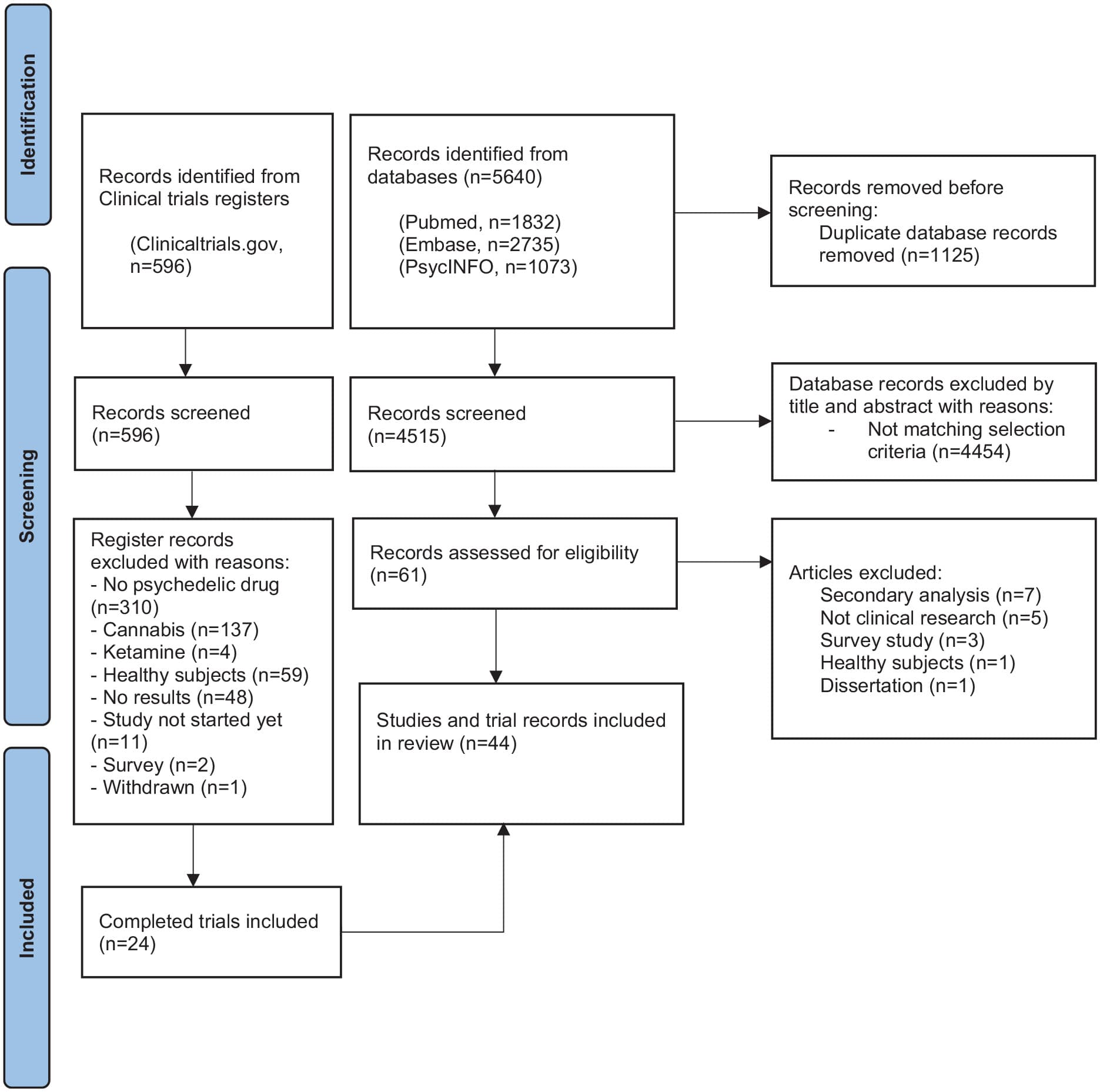

We found 5640 articles (PubMed, n = 1832; EMBASE, n = 2735; PsycINFO, n = 1073). After removal of duplicates, the remaining 3709 titles and abstracts were screened independently by the first two authors. Any discrepancies on inclusions were discussed between multiple authors until consensus was reached. After screening, the full texts of 61 articles were assessed for eligibility; 44 articles were included. We found 596 registered trials; after selection, 24 completed trials were included (see flow diagram, Figure 1).

Included studies were published between 2006 and 2021 and reported on a total of 598 unique participants, of whom 521 received an active dose. Sample sizes varied from 1 to 105 participants (mean n = 23), with mean ages ranging from 25 to 59 years. Multiple publications referring to a single study were merged. All qualitative studies described subsamples from quantitative studies included in this review. There was substantial variation in study design, substances, dosages, and disorders. Four quantitative and two qualitative studies did not report on AEs.

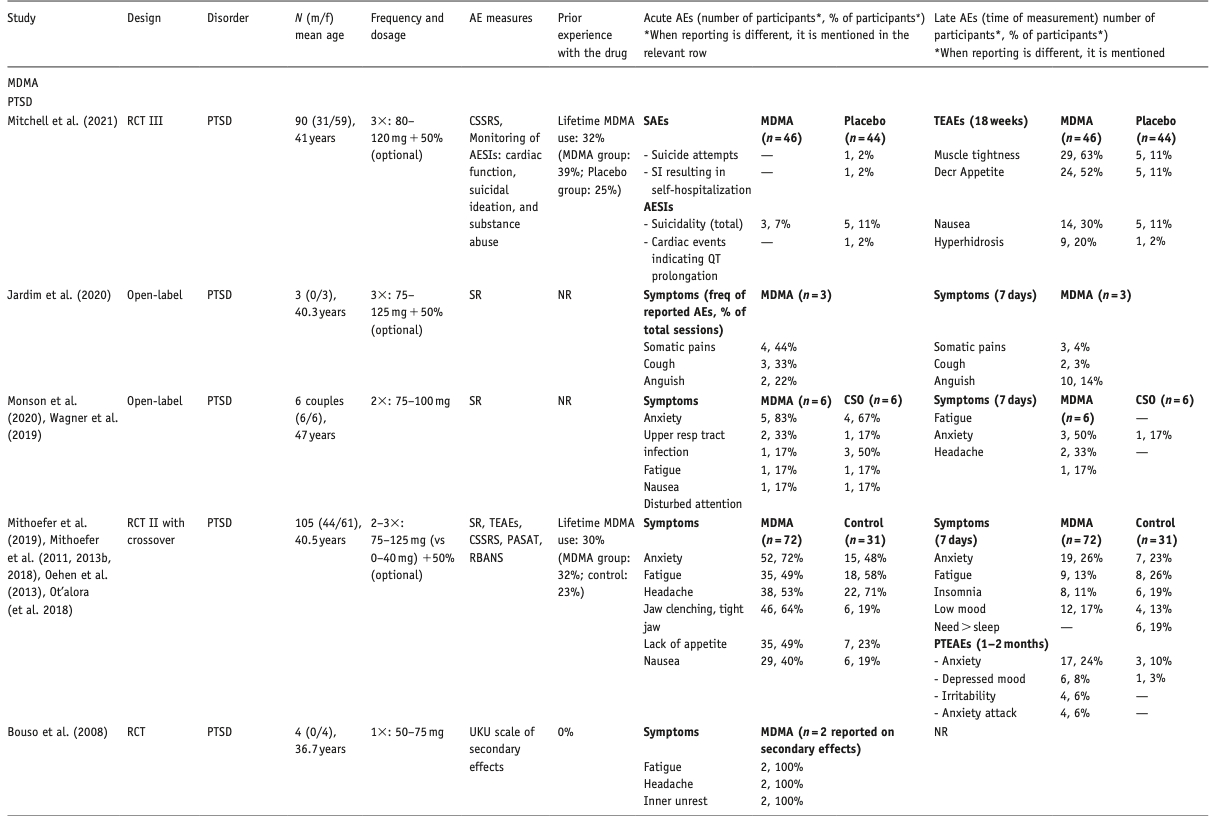

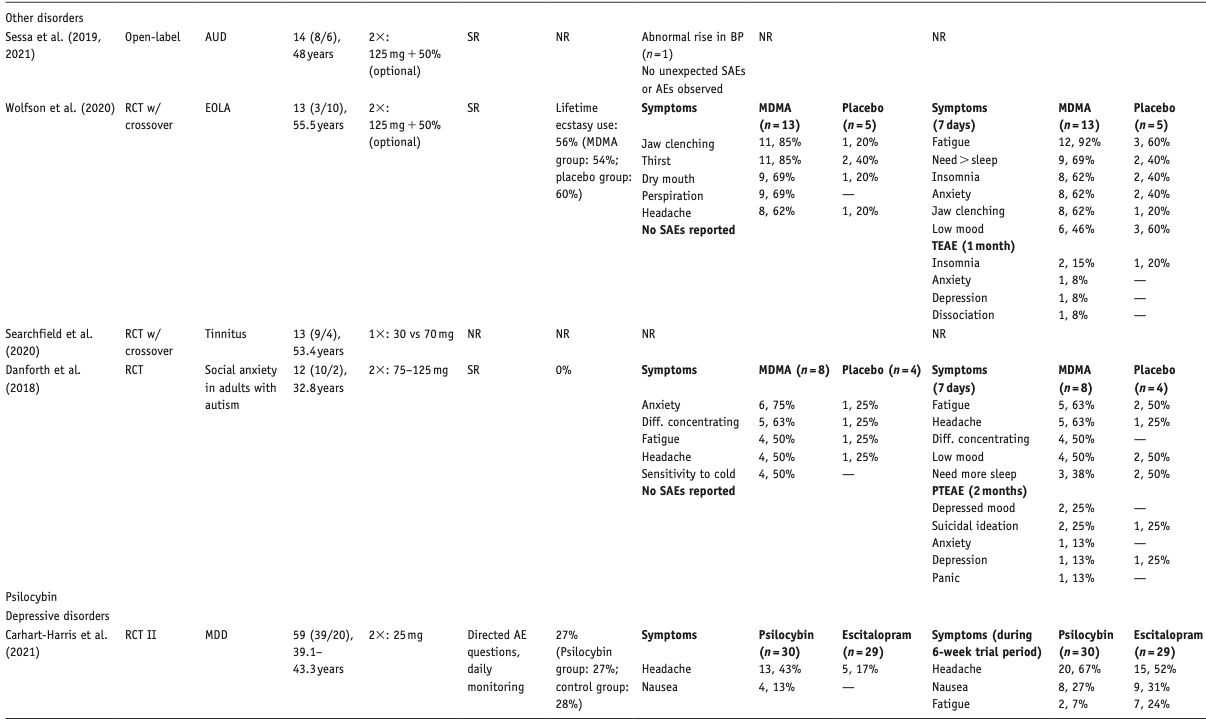

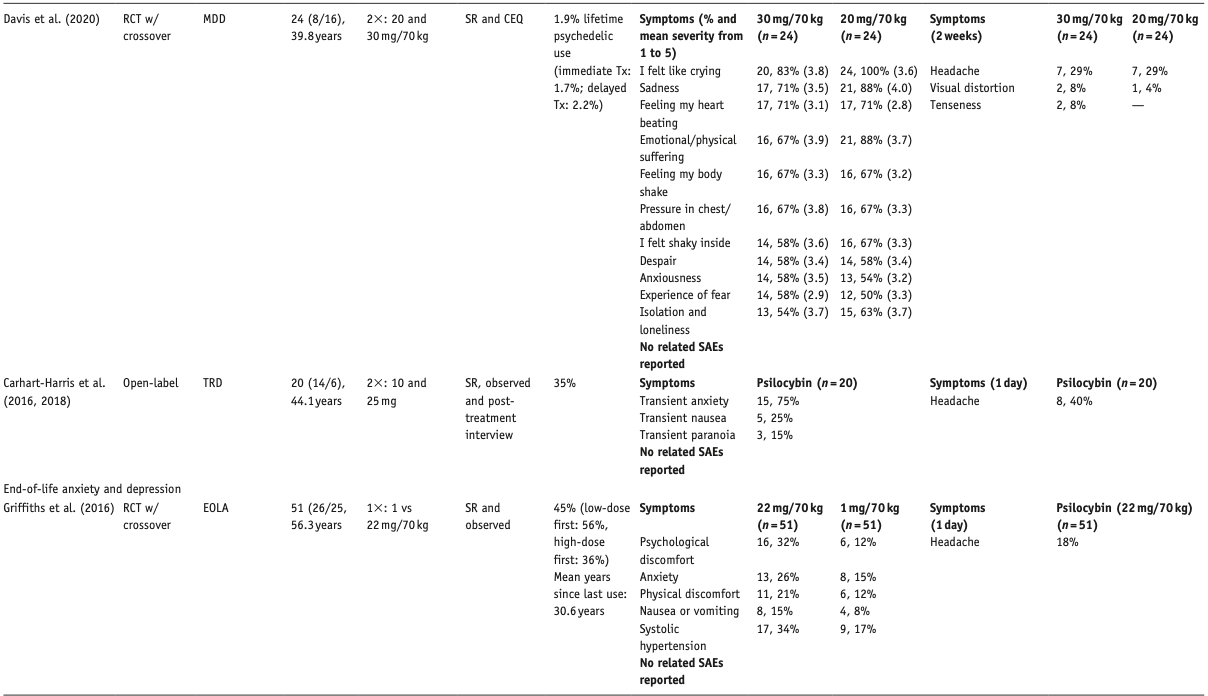

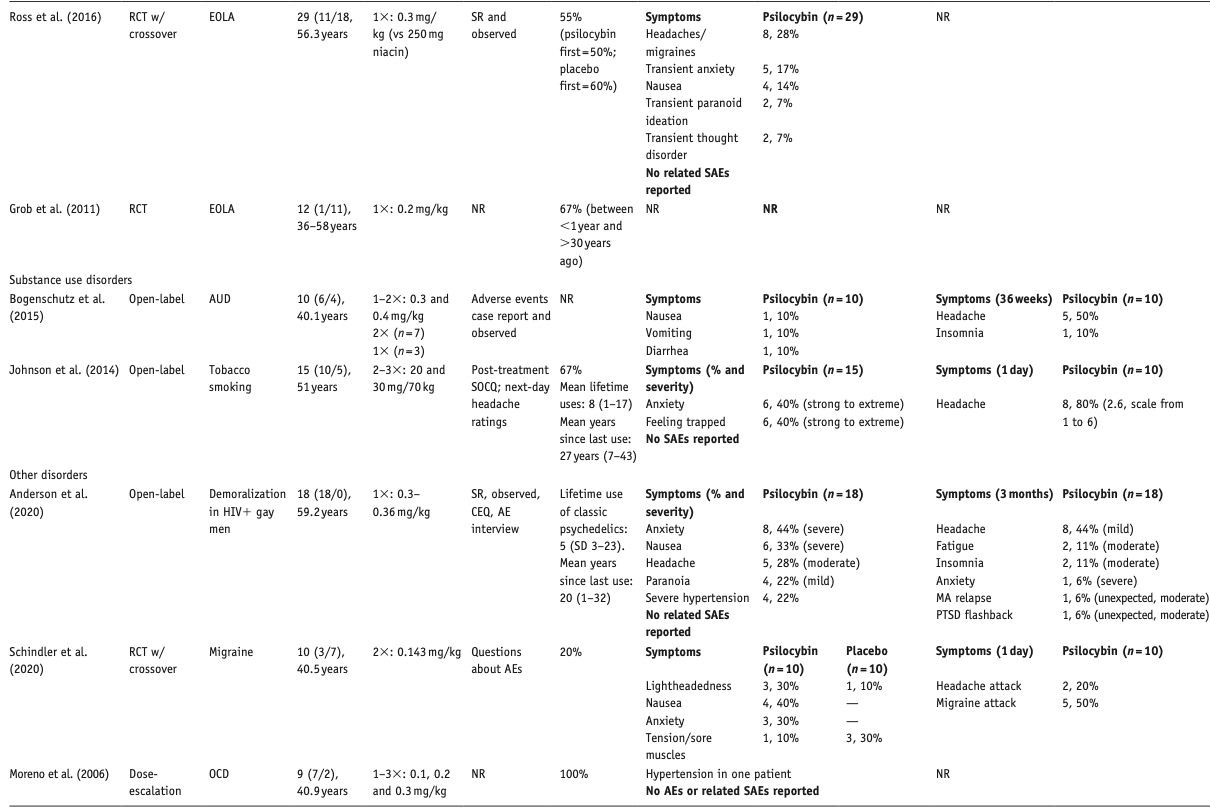

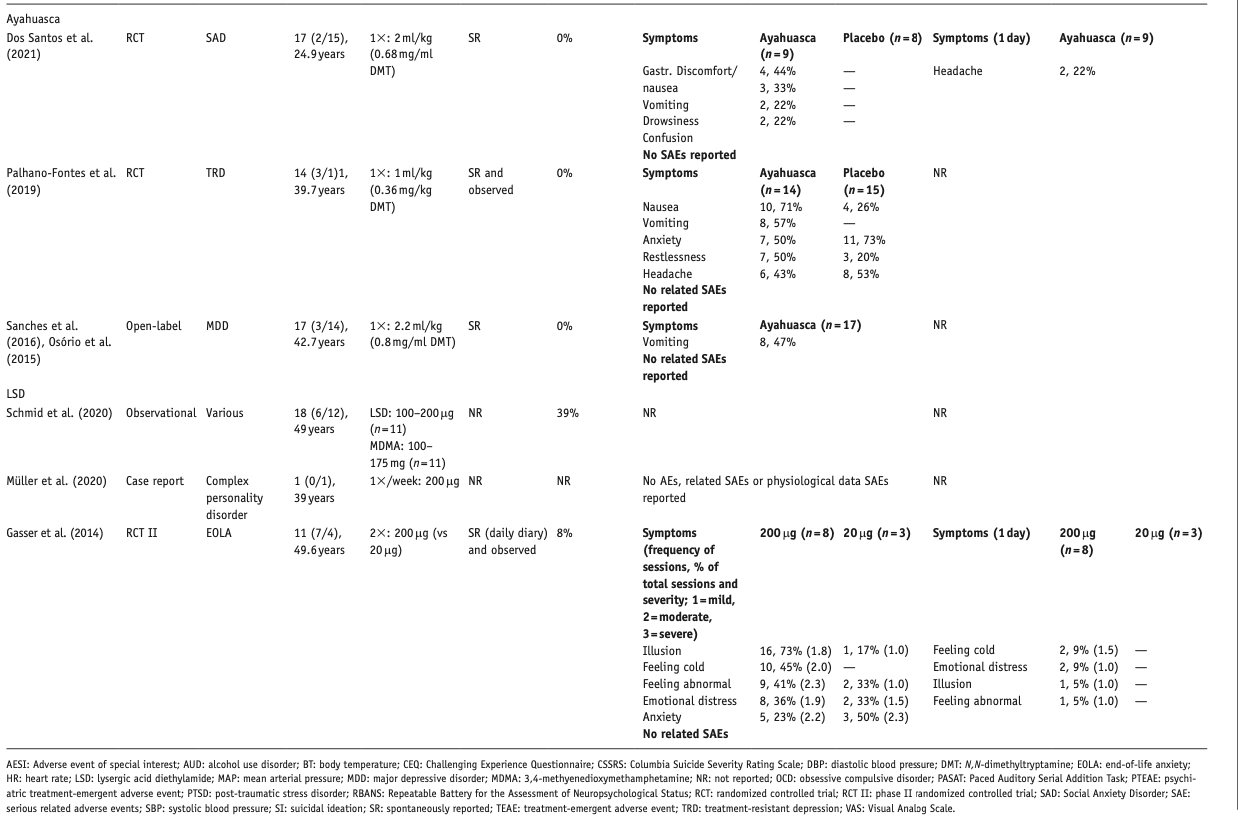

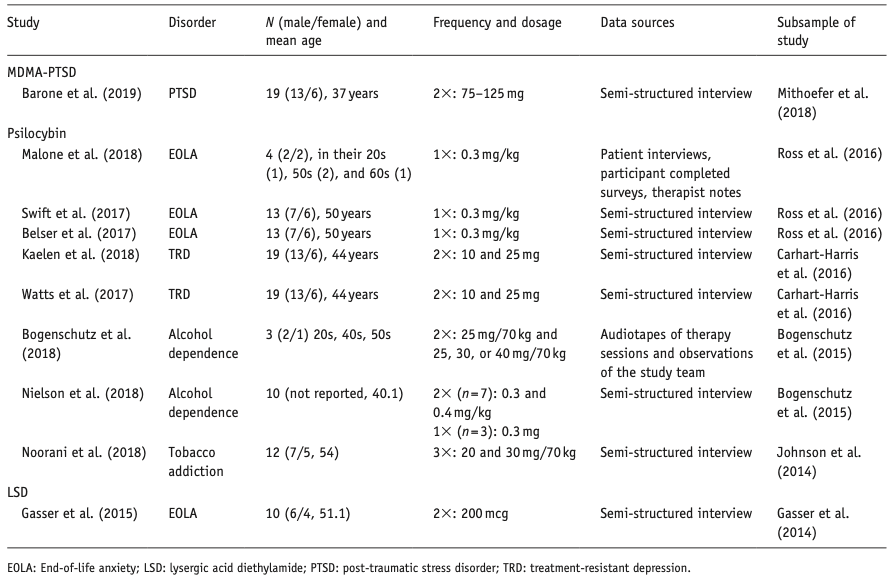

Below, we describe the main results per compound, differentiated per disorder. Table 1 provides an overview of included studies, participants, drug used, prior psychedelic use, AE measurements, and a summary of reported acute and late AEs, including SAEs. For ease of reading, here we only present the 3–5 most reported AEs – a detailed overview of all AEs reported is provided in Supplemental Table S1. Table 2 summarizes all included qualitative studies.

Figure 1. Flowchart.

Table 1. All 34 included quantitative studies.

Table 2. Overview of all 10 included qualitative studies.

MDMA

In all, 16 studies were selected, including one qualitative study (total N = 266 patients treated). In total, 10 publications described MDMA-assisted treatment of PTSD (total N = 214 patients): seven RCTs (Mitchell et al., 2021; Mithoefer et al., 2011; 2013b, 2018, 2019; Oehen et al., 2013; Ot’alora et al., 2018), one open-label trial (Jardim et al., 2020), one case series (Monson et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2019), and one qualitative study (Barone et al., 2019). Other RCTs reported on the treatment of end-of-life anxiety (EOLA) (Wolfson et al., 2020), social anxiety in adults with autism (Danforth et al., 2018), and tinnitus (Searchfield et al., 2020); one open-label study focused on alcohol use disorder (AUD) (Sessa et al., 2019; 2021b). Active doses ranged from 50 to 125 mg (sometimes followed by an optional supplemental half-dose).

Quality appraisal

Of all MDMA studies, 11 reported AEs only when spontaneously reported by participants; one study did not report on AEs (Searchfield et al., 2020). Two RCTs systematically assessed AEs (Mitchell et al., 2021; Mithoefer et al., 2019), another study employed the UKU scale of secondary effects; this was the only study reporting AE severity (Oehen et al., 2013). Six studies did not report whether participants had ever used MDMA or “ecstasy” prior to study participation (Bouso et al., 2008; Jardim et al., 2020; Monson et al., 2020; Ot’alora et al., 2018; Searchfield et al., 2020; Sessa et al., 2021b); prior exposure to MDMA in the other nine quantitative studies varied from none (Danforth et al., 2018) to 56% (Wolfson et al., 2020). The qualitative study was of medium/high quality (Barone et al., 2019) but did not report on AEs.

Physiological effects

Nine studies measured blood pressure, body temperature, and heart rate (HR); all studies reported (mild) transient, statistically significant elevations during the MDMA session. None required medical intervention. One MDMA-related SAE was reported, in which a participant experienced an increase in premature ventricular contractions (also present at baseline), which required one night of hospitalized monitoring, and resolved spontaneously afterwards (Mithoefer et al., 2018).

Adverse events

PTSD

The most common acute physical AEs were jaw clenching and/or tight muscles, headaches, nausea, fatigue, and lack of appetite. Other acute AEs included feeling cold, thirst, dizziness, perspiration, restlessness, nausea, and somatic pains. Anxiety was by far the most common psychological AE. Most acute AEs occurred more often in the MDMA than in the placebo groups, with some exceptions (e.g., one RCT found a slightly higher prevalence of anxiety and fatigue in the placebo group) (Mithoefer et al., 2011). Acute AEs were mild to moderate severe in the single study that reported severity (Oehen et al., 2013). There was no dose-AE relation in the two PTSD studies that assessed different active MDMA doses (Mithoefer et al., 2018; Ot’alora et al., 2018). SAEs were reported in two studies: in one study two patients reported suicidal behavior and suicidal ideation leading to self-hospitalization, these only occurred in the control group (Mitchell et al., 2021); in another study, three out of four SAEs were considered unrelated to the treatment (Mithoefer et al., 2018); one patient developed an exacerbation of pre-existing premature ventricular contractions, which resolved without evidence for cardiac disease, and was considered potentially related (Mithoefer et al., 2018).

In a case study, Wagner and colleagues (2019) illustrate how a (pseudonymized) participant experienced these acute adverse reactions, and how they related to the therapeutic process:

Stuart experienced strong emotional reactions, such as crying and grief in the sessions, and did not try to stop or escape those experiences. He also had strong visceral reactions in the MDMA session, including muscle tightening and sweating as he reviewed traumatic memories while ‘inside’. Following this session, Stuart reflected on this experience as follows: “There’s no easy fix—I need to work through the darkness.”

Common late AEs were fatigue, lack of appetite, low mood, insomnia, need for more sleep, increased irritability, headache, difficulty concentrating, and anxiety. In one study, rates of fatigue, insomnia, and headaches were somewhat higher in the control group (Mithoefer et al., 2019). A minority of patients in this group reported some complaints up to 2 months after the final session, including anxiety (17 of 72 patients), depressed or low mood (6 of 72 patients), and panic attacks (4 of 72 patients), with higher rates in the MDMA than the control group.

End-of-life anxiety

A crossover RCT for EOLA reported jaw clenching, thirst, dry mouth, perspiration, and headache as acute AEs. Fatigue, need for more sleep, insomnia, anxiety, jaw clenching, and low mood were the most common late AEs (Wolfson et al., 2020). Except low mood, all AEs occurred more in the MDMA group. Anxiety, depressed mood, and dissociation were reported only in the MDMA group; insomnia was reported in both groups.

Social anxiety

The RCT on social anxiety in adults with autism reported higher rates of acute AEs in the MDMA than in the placebo group, including anxiety, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, headache, and sensitivity to cold (Danforth et al., 2018). Most prevalent late AEs included fatigue, headache, difficulty concentrating, low mood, and the need for more sleep; all late AEs except the latter two were more common in the MDMA group. Two of the eight patients in the MDMA group, and one of four patients in the placebo group reported depressed mood, suicidal ideation, and panic attack in the period following the first drug session.

Tinnitus and AUD

The studies on AUD and tinnitus treatment did not report on AEs.

Psilocybin

We included 20 articles, describing psilocybin treatment in 257 patients: six (crossover) RCTs, five articles describing four open-label studies, one single-group, pseudo-randomized dose-escalation study, and eight qualitative studies. Three RCTs on EOLA (Griffiths et al., 2016; Grob et al., 2011; Ross et al., 2016), two RCTs on MDD (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2020), one RCT on migraine headaches (Schindler et al., 2020), and one dose-escalation study on obsessive-compulsive disorder (Moreno et al., 2006). Open-label studies investigated the treatment of treatment-resistant depression (TRD; Carhart-Harris et al., 2016, 2018), AUD (Bogenschutz et al., 2015), tobacco smoking (Johnson et al., 2014), and demoralization in older AIDS-survivors (Anderson et al., 2020). Active dosages varied from 10 to 30 mg or 0.1 to 0.4 mg/kg of psilocybin per session. Only two out of six studies that administered different doses of psilocybin reported on adverse effect per dosage (Davis et al., 2020; Griffiths et al., 2016); one study described the timing of AEs per session (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). Qualitative studies described treatment experiences among patients with EOLA (Belser et al., 2017; Malone et al., 2018; Swift et al., 2017), TRD (Kaelen et al., 2018; Watts et al., 2017), and substance use disorder (SUD; Bogenschutz et al., 2018; Nielson et al., 2018; Noorani et al., 2018).

Quality appraisal

Two studies did not report on AEs (Grob et al., 2011; Moreno et al., 2006). Most other studies relied on spontaneous reporting by patient and therapist observations; some (also) used post-treatment interviews, post-day headache ratings, and structured questionnaires, for example, Challenging Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) or States of Consciousness Questionnaire. Three studies reported on AE severity (Anderson et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2014). In the studies that assessed dose–effect relationships, one study found a higher prevalence of some psychological AEs in the moderate-dose (20 mg) than in the high-dose (30 mg) session (Davis et al., 2020) and another study reported a higher prevalence of post-treatment headaches in the higher dose group (Griffiths et al., 2016). One study reported a much higher number of distinct AEs than all other studies (Davis et al., 2020).

With one exception (Bogenschutz et al., 2015), all quantitative studies reported on prior psychedelic use, varying from 20% (Schindler et al., 2020) to 100% (Moreno et al., 2006), averaging 50% of patients with psilocybin or other psychedelic use before the study. One study reported a group average of 0.8 lifetime experiences with psychedelics (Davis et al., 2020); in another study, 39% of the patients had used psilocybin 10 or more times, with 22% reporting “hundreds” of experiences with psychedelics or entactogens (Anderson et al., 2020). Quality of the eight qualitative studies was high; one study reported no AEs (Noorani et al., 2018).

Physiological data

Elevated blood pressure (BP) in the psilocybin group was the most common physiological effect, which was significant in three studies that performed tests of significance (Bogenschutz et al., 2015; Ross et al., 2016; Schindler et al., 2020). Increased HR in the psilocybin group was significant in one study but not in two others. None of the elevations in vital signs required medical intervention. Self-limiting severe hypertension (systolic BP > 180 or diastolic BP > 110 mmHg) occurred in 4 of 18 patients in one study, which seemed related to severe anxiety and resolved upon reassurance by therapists (Anderson et al., 2020). In another study, BP exceeded protocol criteria (diastolic BP > 100 mmHg) in one patient, which resolved without intervention (Davis et al., 2020).

Adverse events

Depressive disorders

A small open-label study on psilocybin treatment for TRD reported anxiety, confusion, and nausea as the most prevalent acute AEs (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). Anxiety occurred mostly prior to sessions and at onset, whereas confusion occurred during the peak of the session. Severity was mild to moderate, except for one case of severe anxiety during a high-dose session. Both MDD RCTs reported headaches (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2020). In one RCT, patients reported moderate to strong emotional and psychological AEs, with patients endorsing statements such as “I felt like crying,” sadness, emotional and/or physical suffering, feelings of grief, and feelings of isolation (Davis et al., 2020). One participant experienced confusing traumatic memories, in which a parent held a pillow over his face, which worsened his depression for several weeks post-treatment (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018; Watts et al., 2017); another patient became incommunicative during the psilocybin session (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018). Two qualitative studies illustrated experiences from a patient perspective:

I worried that I let [the music] shape this sort of melancholy. There was resistance, massively, to everything, every sort of sensory input, I had a fearful response. I was afraid to open my eyes, I was afraid to do anything, I was afraid that this sort of music was the last thing I’d ever hear. (Kaelen et al., 2018)

There was a lot of sadness, really really deep sadness: the loss the grief, it was love and sadness together, and letting go, I could feel the grief and then let it go because holding onto it was hurting me, holding me back. It was a process of unblocking. (Watts et al., 2017)

Post-treatment headache was the only reported late AE; the open-label study only reported headaches in the high-dose (25 mg) group. In one study, 67% rated one of the psilocybin sessions among their top five most psychologically challenging experiences (with 30% rating it the single most psychologically challenging experience (Davis et al., 2020); this was not asked in the other studies (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021).

End-of-life anxiety

Two EOLA studies reported acute and transient AEs in the psilocybin groups, including physical discomfort (headache, nausea) and psychological discomfort (anxiety, transient thought disorders, and suicidal ideation) (Griffiths et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2016). One study did not report on AEs (Grob et al., 2011). Only one study reported headache as a late AE (Griffiths et al., 2016). One patient committed suicide 11 days after a low (placebo like) dose (1 mg) psilocybin session. The patient, reporting feeling bored, wanted to leave this session early, and was subsequently discontinued from the study. The authors concluded that it was an SAE not related to research procedures or to psilocybin (Griffiths et al., 2016).

Three qualitative studies described patient experiences:

It really hit me very strong. And um, it was terrifying. It was just terrifying. It was, um, I was completely disoriented . . . I was really, maybe, in the hold of a ship at sea. Rocking. Absolutely nothing, nothing to anchor myself to, nothing, no point of reference, nothing, just lost in space, just crazy, and I was so scared. And then I remembered that [the therapists] were right there and suddenly realized why it was so important that I get to know them and they to get to know me. And reached out my hand and just said “I’m so scared.” And I think it was [the therapist] who took my hand . . . and said “It’s all right. Just go with it. Go with it.” And um, and I did. (Belser et al., 2017)

Substance use disorders

Two open-label studies investigated psilocybin as a treatment for SUD (Bogenschutz et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2014). One study reported strong (5 of 15 patients) to extreme (1 of 15 patients) anxiety and feeling trapped as acute AEs, and headache as a late AE (2014). The other study reported few AEs (Bogenschutz et al., 2015), although qualitative studies illustrated how frightening the experience was for some:

That whole experience just felt for me like, a fever nightmare. (Nielson et al., 2018)

In the second session, [she] received a higher dose of medication and experienced an amplification of thought moving her into a confused and chaotic state. Underneath the chaotic thinking, she identified a deep well of overwhelming sadness. She was able to eventually surrender control over her thoughts and entered into a state of peacefulness, until her thoughts quieted completely. (Bogenschutz et al., 2018)

Migraines

Most reported acute AEs in the migraine RCT were nausea, anxiety and lightheadedness; headache and migraine attacks were the only late AEs (Schindler et al., 2020). All were more prevalent in the psilocybin group.

Demoralization

The most commonly reported acute AEs in the open-label study on demoralization in gay men were anxiety, nausea, and headache (Anderson et al., 2020). Most of these patients (14 of 18) had transient AEs; nearly half of them reported these AEs as moderate to severe (7 of 18) AEs. Two unexpected late AEs occurred: one patient experienced a post-traumatic flashback, leaving him unable to work for 2 days. Another participant experienced a severe exacerbation of anxiety, followed by a relapse in methamphetamine use, leading to study withdrawal (Anderson et al., 2020).

Ayahuasca

We included three studies, describing 48 patients in total: one RCT in patients with a social anxiety disorder (SAD) (Dos Santos et al., 2021), one RCT in TRD patients (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019), and one open-label study in MDD patients (Osorio et al., 2015; Sanches et al., 2016), all involving a single administration of ayahuasca.

Quality appraisal

None of the studies systematically assessed AEs, and only one reported acute AEs spontaneously reported or observed by therapists (Sanches et al., 2016). At study commencement, all participants were naïve to ayahuasca and most were naïve to other serotonergic psychedelics as well.

Physiological data

No significant HR or blood pressure elevations were observed (Dos Santos et al., 2021; Osorio et al., 2015; Sanches et al., 2016); one study did not report on physiological parameters (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019).

Adverse events

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and anxiety were more common acute AEs in the ayahuasca group, whereas anxiety and headache were more prevalent in the control group in one study (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019). In the TRD study, four patients remained hospitalized for seven days, due to a ‘more delicate condition’ (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019). In the SAD study, one participant experienced an intense episode of transient fear of dying and/or going crazy, distress, and dissociation, which resolved after reassurance by therapists (Dos Santos et al., 2021). In this study, no AEs were reported in the control group. The open-label study only reported vomiting as an acute AE (Osorio et al., 2015; Sanches et al., 2016). No studies reported on late AEs.

LSD

Four studies were included, describing 27 patients in total: one RCT with a nested qualitative study describing EOLA treatment (Gasser et al., 2014, 2015); one observational study on compassionate use of LSD and/or MDMA (Schmid et al., 2020) in group therapy with patients, mostly with PTSD and/or MDD; and one case report on LSD treatment for a complex personality disorder (Müller et al., 2020). Active doses of 100–200 μg were used.

Quality appraisal

AEs were collected through spontaneous reporting by patient and therapist observations. 39% of participants in the compassionate group therapy (Schmid et al., 2020) had prior drug (including cannabis) experience; only one participant (8%) in the RCT did (Gasser et al., 2014). Quality of the qualitative study was medium/high. AE severity was reported only in the RCT (Gasser et al., 2014).

Physiological data

No significant between-group differences were observed on HR or blood pressure (Gasser et al., 2014).

Adverse events

Acute, transient AEs included illusions, feeling cold, feeling abnormal, and anxiety; all but moderate-to-severe anxiety were more prevalent in the high (active) dose groups. Mild-to-moderate emotional distress was of equal severity in the low- and high-dose group. Illusions, feeling abnormal, and feeling cold were also late AEs for one/two patients in the high-dose group. Severity was mostly mild to moderate. Examples of emotional distress and anxiety, as well as later resolution, were described by one patient as follows:

“The first trip was a panic trip. With almost pure fear of death. It was agony . . . Really, I had the feeling ‘that I am dying’. Yes, it was just really black, the black side. I was afraid, shaking. . . . It was total exhaustion, not seeing an exit, no escape. It seemed to me like an endless marathon . . . that was a big part of the trip until it finally led to relaxation . . . During the second trip, the dark side also showed up at the beginning, but for a rather short time. I was a little tensed, sweating, but not for so long and suddenly a phase of relaxation came. Completely detached. It became bright. Everything was light. It became a pleasant feeling, a warm feeling. No pain. Almost a little floating, clear, being carried and together with the music. . . It was really gorgeous. . . . The key experience is when you get from dark to light, from tension to total relaxation” (Gasser et al., 2015)

Discussion

This is the first overview of AEs associated with the clinical use of MDMA and classic serotonergic psychedelics. Using a mixed-methods sequential explanatory design, we combined quantitative measures with qualitative descriptions of patient experiences. Based on this review, MDMA and psychedelics appear to be well tolerated in the treatment of a range of different (mental) disorders. However, caution is warranted, since this conclusion is based on a limited number of relatively small studies with a variety of low- and high-quality designs, using different (and inconsistent) AE assessment procedures, different types of psychedelics used in different doses, in patients with different disorders with relatively high rates of prior experience with psychedelic drug use.

Acute AEs

The most common acute physical AEs in the MDMA groups were fatigue, lack of appetite, feeling cold, thirst, jaw clenching, and perspiration; anxiety and difficulty in concentrating were the most common acute psychological AEs. The most common acute AEs across psilocybin studies were moderate to severe anxiety, headache, and nausea. Acute psychological AEs for psilocybin and LSD (e.g., paranoid thoughts, feeling trapped, illusions, feeling abnormal, psychological discomfort) mostly resolved during sessions, but were sometimes severe. In one ayahuasca study (Dos Santos et al., 2021), a participant temporarily dissociated, fearing he/she was dying or going crazy. Therapist interventions helped resolve this episode by calming this patient down, emphasizing the importance of trained, skilled, and trusting therapists (Mithoefer, et al., 2013a; Phelps, 2017, 2019). Therapist training is also important to familiarize therapists with the contextuality of some AEs, and of effective interventions to prevent or manage them.

Multiple qualitative studies describing occasionally terrifying, frightening, and confusing experiences. In many cases, patients evaluated these experiences retrospectively as therapeutic and beneficial. Nausea and vomiting were common acute AEs in ayahuasca studies. Except for a single case of premature ventricular contractions in one MDMA-treated patient with PTSD, no drug-related AEs and SAEs required medical intervention.

Many of the physiological AEs described in this review are well known from the literature on healthy subjects: for example, nausea, and vomiting with ayahuasca (Dos Santos et al., 2016; Durante et al., 2021; Guimarães dos Santos, 2013; Hamill et al., 2019), headache after psilocybin use (Johnson et al., 2012), and acute, transient elevated vital signs, jaw clenching, perspiration, and lack of appetite with MDMA (Dumont and Verkes, 2006; Liechti et al., 2000; Vizeli and Liechti, 2017; Vizeli et al., 2019; Vollenweider et al., 1998). Across studies and disorders, acute psychological AEs included anxiety, transient paranoia, confusion, despair, and psychological distress were commonly reported, ranging from relatively mild to severe in some cases; most of the AEs resolved during the session.

Late AEs

The most common late AEs across MDMA studies were fatigue, headache, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and low mood. A minority of patients reported anxiety, depression, panic, and suicidal ideation in the days and weeks following treatment sessions. Low mood was a late AE present in both MDMA and placebo groups. Low mood is also commonly reported, 3–4 days after MDMA use, in studies with healthy subjects and by recreational “ecstasy” users (Baggott et al., 2016; Dolder et al., 2018; Kirkpatrick and De Wit, 2014; Liechti et al., 2000, 2001; Vollenweider et al., 1998). However, some studies do not report post-acute decreases in mood (Borissova et al., 2021), including the open-label study on MDMA in patients with an AUD (Sessa et al., 2021a). Patients in control groups may have experienced low mood due to a lack of symptom relief and related disappointment; anxiety in the MDMA groups may be related to re-experiencing traumatic memories and painful emotions. Future research should more accurately qualify anxious states and low mood in the period following MDMA treatment, and to assess whether these are a time-limited element of the therapeutic process or a subacute adverse effect.

One ayahuasca study reported hospitalizing four patients for a week, without further commenting how their ‘delicated condition’ related to the (adverse) effects of ayahuasca (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019). Two studies (Anderson et al., 2020; Watts et al., 2017) reported unexpected adverse reactions (post-traumatic flashback; severe exacerbation of anxiety and drug use relapse; exacerbation of depression) in three patients that occurred several weeks post-psilocybin administration; patients’ conditions deteriorated and required further therapeutic intervention; one patient withdrew from the study. The authors note that these reactions and the high incidence of anxiety, weeks after the session, may be related to the medical complexity and high psychiatric comorbidity of this population (Anderson et al., 2020). Despite the clinical severity of these complaints, they were not reported as SAEs, which carries the risk of underreporting potential negative consequences. On the other hand, the longer the time after treatment sessions, the less likely it is that events are still related to a specific treatment. Since we currently cannot predict individual responses and adverse reactions that may develop in the weeks or months following treatment, it is imperative that researchers and clinicians perform longer term follow-ups and report any untoward reactions.

Recently, several cases were reported in which study participants in an MDMA trial stated that they became suicidal after the trial was finished, including one case in which a participant remained attached to a therapist, and was subsequently abused (Lindsay, 2022; Rosin, 2022). Unfortunately, such very serious transgressions occur in our field, and need to be vigorously addressed if and when they occur (Gutheil and Gabbard, 1993). It might well be that the field of psychedelic treatments is especially at risk, as patients under influence are vulnerable, suggestible and highly dependent on the therapist(s) (Hartogsohn, 2018). Furthermore, therapists may have developed their own personal approaches to therapy that not always adhere to professional codes of conduct (Gutheil and Gabbard, 1998). Apart from that, this also illustrates the importance of thoroughly and systematically monitoring adverse effects.

Suicidality

We found one study in which a suicide, 11 days after a session with a placebo-like dose (1 mg) of psilocybin, was reported as unrelated to study participation (Griffiths et al., 2016). Not included in our review were the results of a recently finalized RCT, comparing a very low (1 mg) to a medium (10 mg) and a high dose (25 mg) of psilocybin in patients with TRD (n = 233). Overall AE rates seem roughly comparable to those summarized in this review. A preliminary (non-peer-reviewed) publication reported suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and/or intentional self-injury—in 7 of the 79 patients (8.8%) in the 25 mg group, in 6 of the 75 patients (8%) in the 10 mg group, and in 4 of the 79 patients (5%) in the 1 mg group; 14 instances in 9 patients were reported as SAEs (Compass Pathways, 2021). These numbers suggest higher suicidality rates in active dose groups (10 and 25 mg), but further interpretation can only be made once peer-reviewed results have been published. Suicidal ideation and behavior were reported in three MDMA studies, although incidence was low, rates were lower or similar in MDMA compared to controls, and SAEs were only reported in the control groups. Nevertheless, scrutinous assessment of treatment-related consequences is warranted. Being randomized to the inactive group, combined with despair and (overly) high expectations in patients with severe disorders may contribute to feelings of hopelessness, and subsequent suicidal ideation and/or behavior. That said, it is important to remember that mental disorders increase the risk of suicidal thoughts in general (Andersson et al., 2022; Nock et al., 2009). Future studies need to carefully asses suicidal ideation, and to explore ways to best support all patients in the long run.

Interpreting adversity

Psychological or emotional “AEs” can be ambiguous, subjective, context dependent, and subject to interpretation. The qualitative studies in this review illustrated how, in hindsight, patients considered working through difficult feelings and emotions as therapeutically beneficial (Barrett et al., 2016; Roseman et al., 2019). This is corroborated by (survey) studies showing that users frequently transform challenging experiences into personally, morally, or spiritually meaningful ones (Barrett et al., 2016; Carbonaro et al., 2016; Gashi et al., 2021; Roseman et al., 2019). The shift in terminology—using “challenging experiences” instead of “bad trips” (AEs)—indicates an increasing acceptance that difficult experiences are inherent to psychedelic treatments (Johnson et al., 2008), and that they can be both distressing and therapeutically beneficial. More narrative evidence as well as the systematic use of specialized questionnaires (e.g., CEQ) can help interpret such experiences and their impact on treatment outcomes. This raises some important issues.

First, since the effects of psychedelics are thought to be influenced substantially by contextual factors, this may extend to adverse effects as well. Treatment designs that reduce or minimize positive contextual components (e.g., time spent preparing patients, number of therapists, strength of the therapeutic relationship, time spent providing aftercare and integration) may increase the incidence of AEs (Erritzoe and Richards, 2017; Oram, 2012, 2016). Second, some aspects of the definitions of “AE” are ill-suited in the context of psychedelic treatment. By definition, AEs are undesired and something to be avoided. Categorizing challenging but potentially therapeutically beneficial experiences as AEs can thus be counterproductive. For instance, framing “anxiety” as adversity may prompt patients to try and avoid difficult feelings and thoughts rather than engaging with them as part of a therapeutic process. Disentangling adverse elements that ought not be part of the therapeutic process (e.g., physical AEs such as headaches and nausea, or exacerbation of distressing symptoms such as suicidal thoughts and dissociation) from psychological experiences that are part of the therapeutic process is crucial to improve our understanding of the mechanisms of action of psychedelic treatments. To illustrate the complexity of this challenge: vomiting, the most commonly reported AE in ayahuasca studies, is often considered a therapeutic element both in traditional indigenous and in “neoshamanic” ayahuasca practices (Fotiou and Gearin, 2019). In the case of anxiety, the severity and the length of the difficult episode may also predict suboptimal or even negative clinical outcomes (Carbonaro et al., 2016; Roseman et al., 2018). Careful screening, preparation, session monitoring, psychological support, and post-session integration are crucial prerequisites to maintain a low incidence of AEs and to maximize therapeutic efficacy (Johnson et al., 2008; Strassman, 1984). In the absence thereof, young people, and those high in the personality traits of neuroticism emotional lability, and/or low in absorption, openness to experience, and acceptance, as well as those in a apprehensive, preoccupied or confused mental state may be more prone to challenging experiences, which can worsen their pre-existing problems (Aday et al., 2021; Barrett et al., 2017; Studerus et al., 2012). Finally, recent articles have described how psychedelics may alter metaphysical or ontological beliefs (Nayak and Griffiths, 2022; Timmermann et al., 2021). Such experiences may be highly meaningful but can also induce an “ontological shock,” particularly when conflicting with prior held religious, personal, or spiritual beliefs (Breeksema and Van Elk, 2021). This introduces ethical and metaphysical challenges, and a deep responsibility for therapists to mitigate potential adversity when patients are confronted with profound metaphysical experiences (Timmermann et al., 2022).

Limitations

The current review has both strengths and limitations. An important strength is the systematic collection of studies and the combination of quantitative and qualitative studies. However, this review also has some important limitations. A first limitation is that, included studies were mostly small, varied in study design, (dose of) psychedelic drug, and demographics, making comparisons difficult and performing a meta-analysis impossible. Second, only few studies assessed AEs consistently or systematically. Unfortunately, this is a general problem in psychopharmacology (Coates et al., 2018) and not unique for psychedelic drug studies. Instead, most studies relied on spontaneously reported and/or therapist-observed AEs. Spontaneous reporting depends on individual and contextual factors enabling patients to recall or discuss negative experiences. Therapist observation is similarly ambiguous, as observations may be colored by their subjective perception and interpretation. Five pilot studies did not report any AEs (Bouso et al., 2008; Grob et al., 2011; Moreno et al., 2006; Searchfield et al., 2020; Sessa, et al., 2021b). While it is possible—although unlikely—that no AE occurred, not reporting any AE is reminiscent of important omissions in early psychedelic research, when researchers often did not fully disclose the frequency and severity of negative reactions (Rucker et al., 2018). Third, there are not enough placebo-controlled trials to warrant strong conclusions about the causal relation between the psychedelic treatment and AEs; effectively blinding study participants to their treatment condition is notably hard in psychedelic drug studies (Aday et al., 2022; Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2021), particularly given the high percentages of patients who have had previous experience with a psychedelic. Also, due to the small sample sizes, studies may have missed AEs that occur less frequently, hindering extrapolation as some AEs may only become apparent in larger populations. All studies in our review refer to a total of 598 unique patients—of whom 521 received an active dose. Fourth, severity and onset timing of AEs (particularly for late AEs) was reported in only a few studies, hampering adequate interpretation of reported AEs. Next, most trials had strict criteria for participation, with extensive screening and excluding patients with almost any comorbid mental disorder. This includes a personal (or first-degree family) history of psychotic, bipolar, dissociative identity, eating, and SUDs, and active suicidal ideation, all of which are frequently found in patients with more severe mental disorders. Sixth, many studies included patients with previous experience with the experimental drug; up to 56% for MDMA and roughly half of all psilocybin study participants had prior experience(s) with psilocybin or other serotonergic psychedelics. Intensity of drug effects and experienced difficulties appear to be lower and less severe in those with past experience with these drugs (Aday et al., 2021), limiting generalizability to broader patient populations. Moreover, minorities are underrepresented in clinical research with psychedelics (Michaels et al., 2018). It is, therefore, possible that psychedelic-naïve patients with a different socio-cultural background and more severe forms of psychopathology may have more intense experiences, or experience more difficulties coping with potentially disruptive events (Griffiths et al., 2006). That said, the only study in our review that compared lifetime psychedelic use and degree of experienced challenge within the session (as measured with the CEQ) found no significant correlations, suggesting that previous experience does not necessarily predict the occurrence of AEs in clinical populations or contexts (Anderson et al., 2020). Seventh, while qualitative studies helped contextualize some of the acute challenging experiences, these were not always specifically designed to explore such effects. Furthermore, qualitative studies are unevenly divided and relatively scarce; there were none on ayahuasca, only one on MDMA and LSD, and eight on clinical psilocybin studies. Finally, any conclusion on the frequency and interpretation of AEs should consider the target population (set) and the context of the treatment (setting). More information should be given about “set and setting” when reporting and interpreting the results of clinical trials with psychedelics.

Conclusions

This first review of acute and late AEs in the treatment with serotonergic psychedelics and MDMA, combining quantitative and qualitative studies, shows that all compounds acutely induce transient headaches, nausea, and anxiety. Anxiety covers a wide range of psychologically challenging events that may also be beneficial for the therapeutic process. Disentangling truly AEs from potentially beneficial effects is complex but crucial to improve our understanding of psychedelic treatments. SAEs seem to be largely absent based on the included studies, as were lasting physiological side effects. Suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior were rare but did occur; these constitute a serious psychiatric emergency, which emphasizes the importance to investigate which patients are most at risk and how to best reduce the likelihood of their occurrence. Overall, AEs were inconsistently defined and inadequately assessed. Future studies should describe timing and severity of effects more extensively, for example, using scales such as the CEQ. Many studies included patients with prior psychedelic experience, which may bias results and limit generalizability. Qualitative research can also add nuance by detailing and understanding the meaning of challenging experiences. Full transparency about AEs is a responsibility of clinicians, particularly in a nascent field fueled by the enthusiasm of pioneering researchers. Understanding the full spectrum of unpleasant, potentially harmful, and transformative treatment-related events is crucial to inform future therapists who may otherwise be sub-optimally prepared to handle challenging and potentially destabilizing patient experiences, particularly in larger groups of patients with more complex and potentially comorbid conditions.