Abstract

Background: Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been linked with risky health-related behaviors and poor health.

Objective: This study aimed to investigate associations of ACEs with a broad panel of sexual risk-taking behaviors and non-consensual sexual experiences among young people in Denmark.

Participants and setting: Baseline questionnaire data from 15 to 29-year-old participants in the nationally representative cohort study Project SEXUS were used in combination with data from Danish national registers to include a total of 13,132 individuals.

Methods: In logistic regression analyses, confounder-adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained for associations of five ACE categories (Household challenges, Loss or threat of loss, Material deprivation, Abuse, and Neglect) and a cumulative ACE score with measures of sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences.

Results: Statistically significant associations were observed between ACEs and multiple sexual risk-taking behaviors and non-consensual sexual experiences with particularly increased odds among individuals with a history of Abuse, Neglect, or an ACE score of 3 or more. Specifically, Abuse was associated with having received payment for sex (women: aOR 5.38; 95 % CI 2.73–10.61; men: aOR 2.11; 95 % CI 1.22–3.64), with having paid for sex (men: aOR 1.88; 95 % CI 1.41–2.51), and with having been the victim of a sexual assault after age 18 years (women: aOR 3.33; 95 % CI 2.36–4.68).

Conclusions: In this Danish study, multiple measures of sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences were markedly more common among young people with ACEs than in those without ACEs. This knowledge should be considered in future initiatives to promote sexual health among young people.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are public health concerns with significant physical and mental health implications for the affected individuals. Prior research has established associations between ACEs and unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and drug use, as well as a broad range of negative health consequences, including increased risks of cancer, diabetes, depression, anxiety, and suicidality (Bellis et al., 2015; Campbell et al., 2016; Dube et al., 2001; Felitti et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2017).

Links between ACEs and risky sexual behaviors, such as lack of contraception use, high sexual partner numbers, and non-consensual sexual experiences have also been reported (Hillis et al., 2000; Hughes et al., 2017; Ports et al., 2016), and studies indicate that ACEs may cause personal boundary issues, lead to insecure social attachment, and disrupt the ability to form long-term relationships. They may thus play an important role in forming sexual behaviors later in life (Anda et al., 2006; Briere et al., 2002). Growing up in a family unable to provide adequate protection and care may ultimately result in the inability to muster self-protection, thereby rendering individuals with a history of ACEs particularly vulnerable to risky sexual situations and potential sexual victimization (Hillis et al., 2001).

Sexual risk-taking is commonly reported by young Danes as revealed by baseline findings from the large and nationally representative Project SEXUS cohort study, where more than half (51 %) of 15–24-year-old participants reported having had sex with a person who was not their regular partner without using barrier protection within the last year (Frisch et al., 2019). Furthermore, national incidence data in Denmark have revealed that the number of chlamydia diagnoses increased by 60 % from 25.972 cases in 2011 to 41,634 cases in 2022, with 15–29-year-old individuals accounting for the vast majority of cases (Statens Serum Institut, 2023). Non-consensual sexual experiences also occur at high rates among young Danish women, with 11.3 % of 15–24-year-old women reporting at least one sexual assault (Frisch et al., 2019).

Sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences are associated with a range of negative health consequences affecting both physical, mental, and reproductive health (Edgardh, 2000; Kaestle et al., 2005; Ports et al., 2016). Furthermore, such risky behaviors and unwanted sexual experiences have been linked with psychosocial challenges such as school problems and involvement in delinquent acts (Orr et al., 1991). A better understanding of the interplay between childhood adversities and sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults may help to ensure effective and targeted preventive initiatives aimed to reduce sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences along with their associated negative health consequences. To this end, we investigated the association of ACEs with a comprehensive battery of sexual risk-taking behaviors and non-consensual sexual experiences among 15–29-year-old participants in a large, nationally representative study in Denmark.

2. Methods

2.1. Study and participants

We used baseline questionnaire data collected in 2017–2018 in Project SEXUS, a prospective cohort study in Denmark focusing on sexual health and the interplay between sexual and general health (www.projectsexus.dk ). A probability-based sample of 62,675 15–89-year-old Danish citizens provided responses to a self-administered online questionnaire yielding a participation rate of 34.6 % according to The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR response rate 1; The American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2016). For the present study, which was developed after the establishment of the Project SEXUS cohort study, we included 13,132 participants who were 15–29 years old on the day they completed the questionnaire.

2.2. Questionnaire data

The multi-item questionnaire, which had been developed, cognitively validated, subjected to peer review among sexual health experts, and tested in a pilot study comprising 3000 individuals, included >600 items covering participants' family-related and sociodemographic background, health, lifestyle, and sexuality (Frisch, 2022). To include as many topics as possible, while ensuring that each participant was presented with a manageable number of items, a small fraction of questions were only posed to a random subset comprising approximately half of the participants, while others were posed to the other half, and logical filter questions ensured that each participant was presented with a median of 180 questions. For 6656 of the 13,132 15–29-year-old participants, questionnaires contained items concerning ACEs.

2.3. Register data

Questionnaire data for participants were combined with data from nationwide administrative and health registers in March 2022. Complete individual-level data linkage was ensured via the unique 10-digit personal identification number ascribed to every Danish citizen. Access to register data was granted by Statistics Denmark and the Danish Health Data Authority and included information from the following registers: the Civil Registration System (Pedersen, 2011), the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (Mors et al., 2011), the National Patient Register (Lynge et al., 2011), the Danish National Prescription Register (Pottegård et al., 2017), the Register of Support for Children and Adolescents (Danmarks Statistik, 2022), and the Income Statistics Register (Baadsgaard & Quitzau, 2011).

2.4. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

We used register information and questionnaire data to define a total of 17 ACEs. For all 13,132 participants, linked register data were used to define the following 13 ACEs: Parental separation, Parental psychiatric illness, Parental alcohol abuse, Parental drug abuse, Sibling psychiatric illness, Need for preventive measures by social services, Parental death, Parental severe somatic illness, Sibling death, Sibling severe somatic illness, Household poverty, Parental unemployment, and Parental early pension. All 13 register-derived ACEs were measured during ages 0 through 17 years or, for participants younger than 18 years, until the date when they completed the questionnaire, and were inspired by a similar set of register-based ACEs used by other researchers (Bengtsson et al., 2019; Rod et al., 2020). Questionnaire data for 6656 participants were used to capture four additional ACEs before age 18 years or, for younger respondents, before the date when they completed the questionnaire: Psychological abuse, Physical abuse, Sexual abuse, and Unsafe childhood without closeness and care (Frisch, 2022).

The total of 17 ACEs were grouped in the following five ACE categories: Household challenges (Parental separation, Parental psychiatric illness, Parental alcohol abuse, Parental drug abuse, Sibling psychiatric illness, and Preventive social initiatives), Loss or threat of loss (Parental death, Parental severe somatic illness, Sibling death, and Sibling severe somatic illness), Material deprivation (Household poverty, Parental unemployment, and Parental early pension), Abuse (Psychological abuse, Physical abuse, and Sexual abuse), and Neglect (Unsafe childhood without closeness and care). Additionally, for those 6656 participants with both register-based and questionnaire-based information about ACEs, we calculated an overall ACE score (0, 1–2, or 3+) by counting the number of individual ACEs for each participant. Definitions and categorizations of all ACEs are provided in Table S1.

2.5. Sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences

To capture sexual debut before the legal age of consent in Denmark (15 years), respondents with interpersonal sexual experience were asked at what age they had their sexual debut. To identify a group with high numbers of sex partners of the other sex, percentiles of the reported total number of other-sex sexual partners were calculated for each one-year age group to take the strong age-dependence into account, and participants in the highest age group-specific quintiles were considered to have the outcome. Engagement in unsafe sex was captured by asking participants who reported vaginal, oral, or anal sex within the last year whether they had engaged in either of these practices with a person who was not their regular partner without using a condom or other barrier contraception. Participants who had engaged in any such unprotected sexual practice within the last year were considered to have practiced unsafe sex. Sexually experienced participants were asked if a doctor had ever diagnosed them with a sexually transmitted infection, if they had ever received payment for sex, if they had ever paid for sex and, among women, if they had ever had an induced abortion of an unwanted pregnancy.

Regarding non-consensual sexual experiences, respondents were asked if they had ever experienced the distribution of nude pictures of themselves on social media without their consent, if they had ever experienced a sexual assault (involvement in non-consensual sexual acts based on threats, force, or violence at or after age 18 years), and if they had ever experienced workplace sexual harassment (someone at their workplace making sexual advances in an unpleasant manner). Participants who answered that they had had such experiences at least once were considered to have the non-consensual sexual experience in question.

2.6. Statistical analyses

We estimated the prevalence of background sociodemographic and health-related variables among study participants. Using binary logistic regression, we calculated adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between each of the five ACE categories and the abovementioned measures of sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences. In all analyses we stratified by sex and adjusted for potential confounding by age (15–17, 18–20, 21–23, 24–26, 27–29 years), cultural background (non-Muslim, Muslim), region of residence (Capital region of Denmark, Region Zealand, Region of Southern Denmark, Central Denmark Region, North Denmark Region), household's highest educational level at respondent's 15th birthday (<10, 10–12, >12 years), history of treatment by a doctor for a long lasting or severe physical disease (no, yes), history of treatment by a doctor, psychologist or similar professional for a mental health problem (no, yes), and sexual identity (heterosexual, non-heterosexual). As described elsewhere, we applied an individual weighting procedure to ensure national representativeness of our findings with regard to sex, birth year, region of residence, marital status, cultural background and twin status (Andresen et al., 2022; Frisch et al., 2019).

All statistical analyses were carried out using the SvyVGAM package in R, version 4.0.2.

2.7. Ethics

According to Danish law, register- and questionnaire-based studies do not require approval by The Scientific Ethical Committee system. Before study onset, institutional approval at Statens Serum Institut (nos. 21-00053 and 22-00210) was obtained to ensure compliance with the European Union's general data protection regulation (GDPR). To preserve confidentiality, all data analyses were performed using a pseudonymized dataset.

3. Results

3.1. Participants' background characteristics and overall distributions of ACEs and sexual outcomes

Overall, our 15–29-year-old study population consisted of 8197 women and 4935 men, and the median age was 22 years for both sexes (Table 1). Study participants were predominantly of non-Muslim cultural background (women: 94.9 %; men: 96.6 %), around one third (women: 33.0 %; men: 31.0 %) lived in the Capital Region of Denmark, and more than half (women: 53.4 %; men: 56.3 %) came from households with high educational attainment. 15.1 % of women and 13.1 % of men had ever been treated for a long-lasting or severe physical disease, and 39.0 % of women and 22.4 % of men had ever been treated for a mental health problem. The vast majority of study participants (women: 85.6 %; men: 91.7 %) identified as heterosexuals.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and health-related characteristics among 13,132 15–29-year-old Project SEXUS participants, Denmark 2017–2018

Women N% | Men N% | |

|---|---|---|

Total | 8197 (100) | 4935 (100) |

Age | ||

15–17 years | 1355 (18.9) | 848 (19.8) |

18–20 years | 1768 (24.1) | 1061 (23.8) |

21–23 years | 1773 (20.3) | 1014 (20.0) |

24–26 years | 1720 (19.4) | 999 (18.4) |

27–29 years | 1581 (17.3) | 1013 (18.0) |

Median | 22 years | 22 years |

Cultural background | ||

Non-Muslim | 7926 (94.9) | 4780 (96.6) |

Muslim | 271 (5.1) | 155 (3.4) |

Region of residence | ||

Capital Region of Denmark | 2727 (33.0) | 1643 (31.4) |

Region Zealand | 854 (12.6) | 529 (13.2) |

Region of Southern Denmark | 1597 (20.2) | 1009 (20.6) |

Central Denmark Region | 2023 (24.1) | 1165 (24.1) |

North Denmark Region | 996 (10.2) | 589 (10.6) |

Household educational level in childhooda | ||

Low (<10 years) | 483 (6.1) | 288 (5.8) |

Medium (10–12 years) | 3348 (40.4) | 1859 (37.9) |

High (>12 years) | 4329 (53.4) | 2766 (56.3) |

Ever treated by a doctor for a long-lasting or severe physical disease | ||

No | 6757 (84.9) | 4169 (86.9) |

Yes | 1216 (15.1) | 632 (13.1) |

Ever treated by a doctor, psychologist or similar professional for a mental health problem | ||

No | 4912 (61.0) | 3788 (77.6) |

Yes | 3180 (39.0) | 1099 (22.4) |

Sexual identity | ||

Heterosexual | 7039 (85.6) | 4522 (91.7) |

Homosexual | 99 (0.9) | 131 (2.2) |

Bisexual | 506 (6.2) | 132 (2.8) |

Asexual | 44 (0.5) | 9 (0.2) |

Cannot be placed in the abovementioned categories/do not know/undecided | 509 (6.7) | 141 (3.1) |

N (%) = number of respondents and corresponding demographically weighted percentage.

aHousehold educational level in childhood determined by the highest education among household members at respondent's 15th birthday.

Participants' ACEs and associated ACE categories are shown in Table S1. The most common ACE category was Household challenges, which was reported by 43.7 % of women and 42.8 % of men. Loss or threat of loss was reported by 29.9 % of women and 30.4 % of men, and Material deprivation by 20.9 % of women and 18.4 % of men. Abuse was reported by 24.6 % of women and 17.6 % of men, whereas Neglect was reported by 4.5 % of women and 5.3 % of men.

Participants' reported overall sexual risk-taking behaviors and non-consensual sexual experiences were as follows: 20.7 % of women and 18.1 % of men had had their sexual debut before the legal age of consent, 41.1 % of sexually experienced women and 44.3 % of sexually experienced men reported unsafe sex within the last year, 28.2 % of sexually experienced women and 19.6 % of sexually experienced men had ever been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection, 1.8 % of women and 2.5 % of men had ever received payment for sex, 0.1 % of women and 11.3 % of men had ever paid for sex, 8.9 % of women had ever had an induced abortion of an unwanted pregnancy, 3.6 % of women and 1.1 % of men had experienced non-consensual distribution of nude pictures on social media, 5.4 % of women and 0.8 % of men had been the victim of a sexual assault at or after the age of 18 years, and 19.1 % of women and 6.4 % of men had experienced workplace sexual harassment.

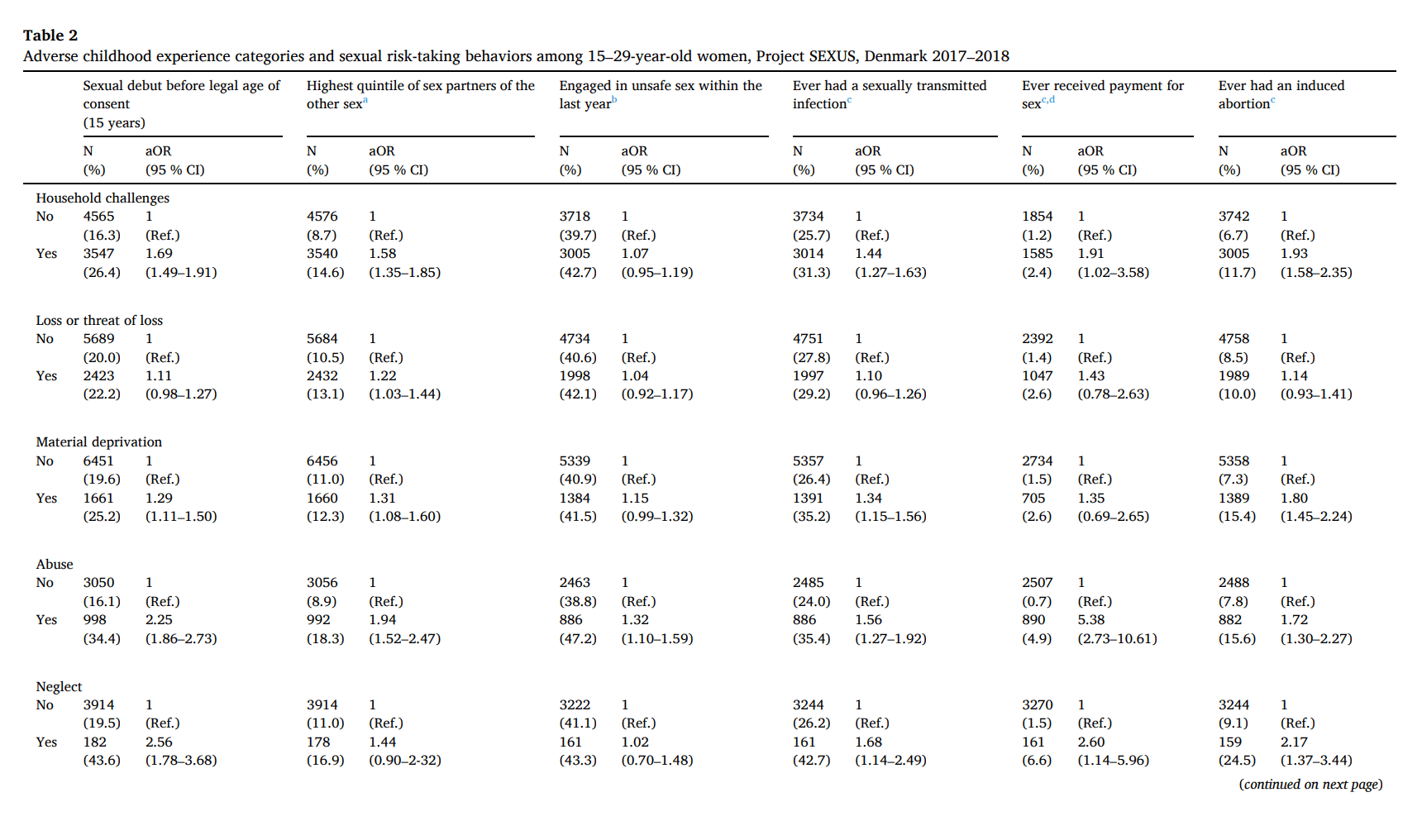

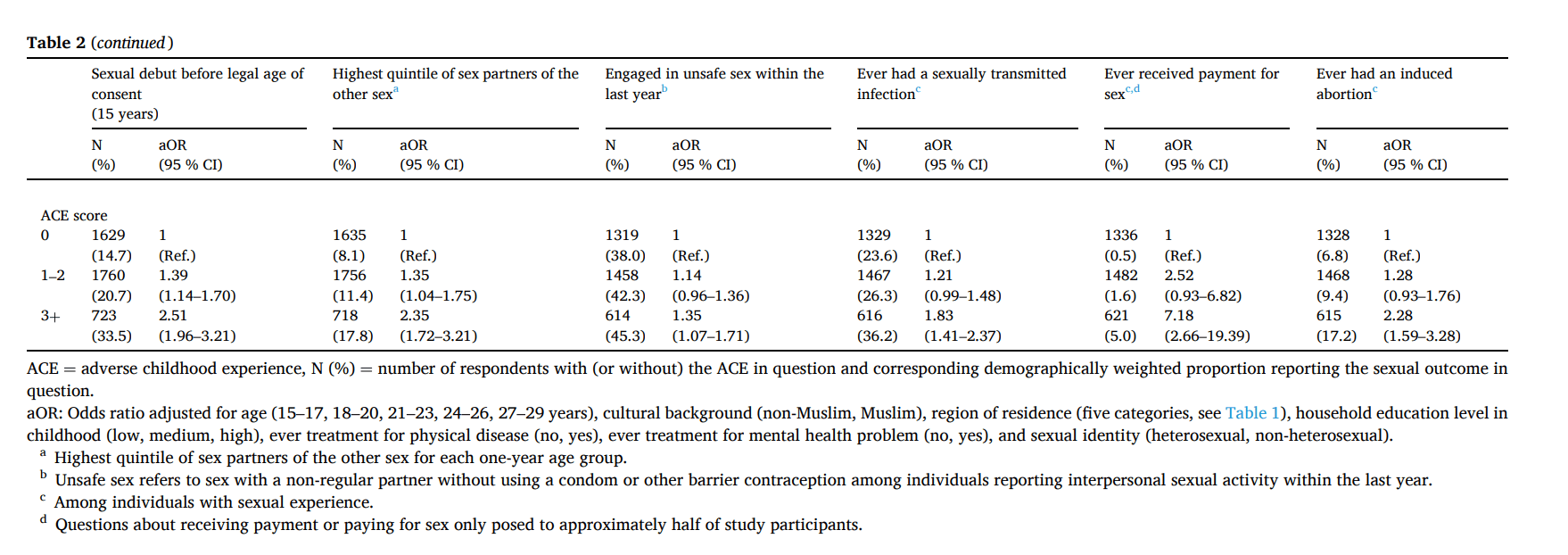

3.2. Associations of ACE categories with sexual risk-taking behaviors among women

Table 2 shows that, among women, all ACE categories were statistically significantly associated with at least one of the examined sexual risk-taking behaviors. Generally, women who reported ACEs categorized as Abuse or Neglect had higher odds of sexual risk-taking than women reporting ACEs categorized as Household challenges, Loss or threat of loss, or Material deprivation. For instance, Abuse (aOR 5.38; 95 % CI 2.73–10.61) and Neglect (aOR 2.60; 95 % CI 1.14–5.96) were both strongly associated with having received payment for sex. Moreover, increasing ACE scores were consistently positively associated with greater sexual risk-taking. Women reporting 3+ ACEs had statistically significantly higher odds of all sexual risk-taking outcomes than those reporting no ACEs, with aORs ranging from 1.35 (95 % CI 1.07–1.71) for having engaged in unsafe sex within the last year to 7.18 (95 % CI 2.66–19.39) for having received payment for sex.

Table 2. Adverse childhood experience categories and sexual risk-taking behaviors among 15–29-year-old women, Project SEXUS, Denmark 2017–2018

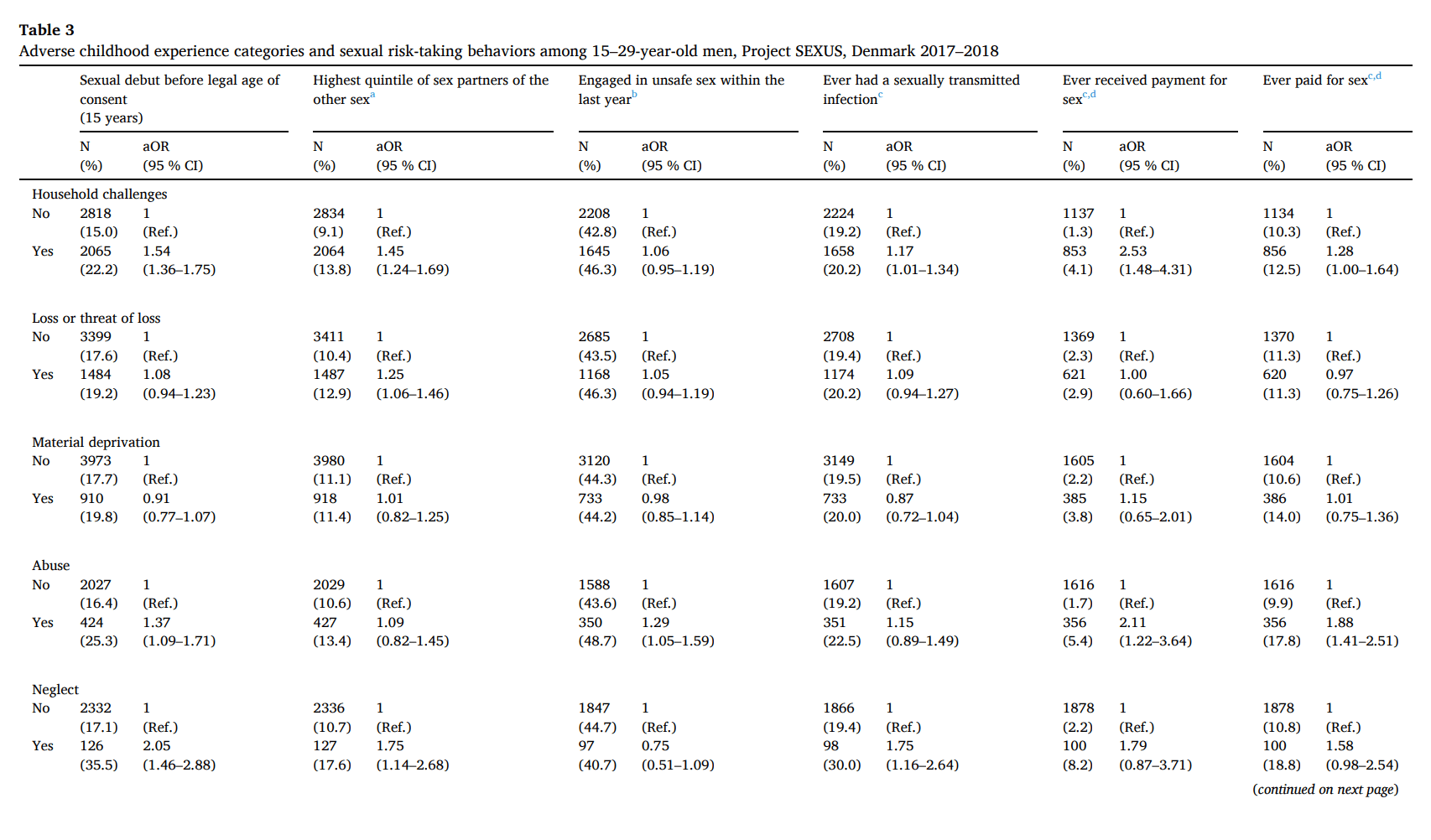

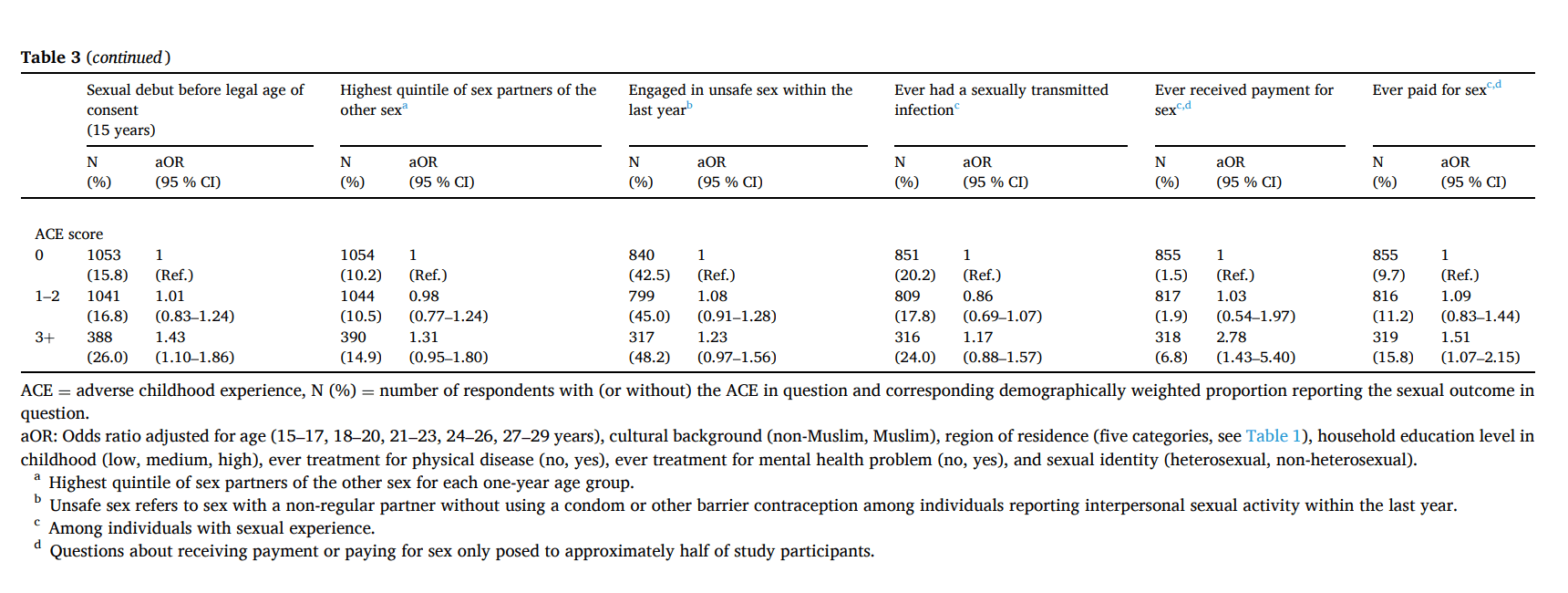

3.3. Associations of ACE categories with sexual risk-taking behaviors among men

As seen in Table 3, men who had experienced Household challenges, Abuse or Neglect, and those with ACE scores of 3 or more, reported statistically significantly more sexual risk-taking behaviors than men who grew up with no ACEs. With aORs close to 1, Material deprivation was not statistically significantly associated with any of the examined sexual risk-taking behaviors, and Loss or threat of loss was significantly associated only with being in the highest age-specific quintile with respect to number of other-sex sexual partners. Strongest associations were seen for receiving payment for sex, where men who had experienced Household challenges (aOR 2.53; 95 % CI 1.48–4.31) or Abuse (aOR 2.11; 95 % CI 1.22–3.64), and men with ACE scores of 3 or more (aOR 2.78; 95 % CI 1.43–5.40) reported having received payment for sex significantly more often than those reporting no ACEs.

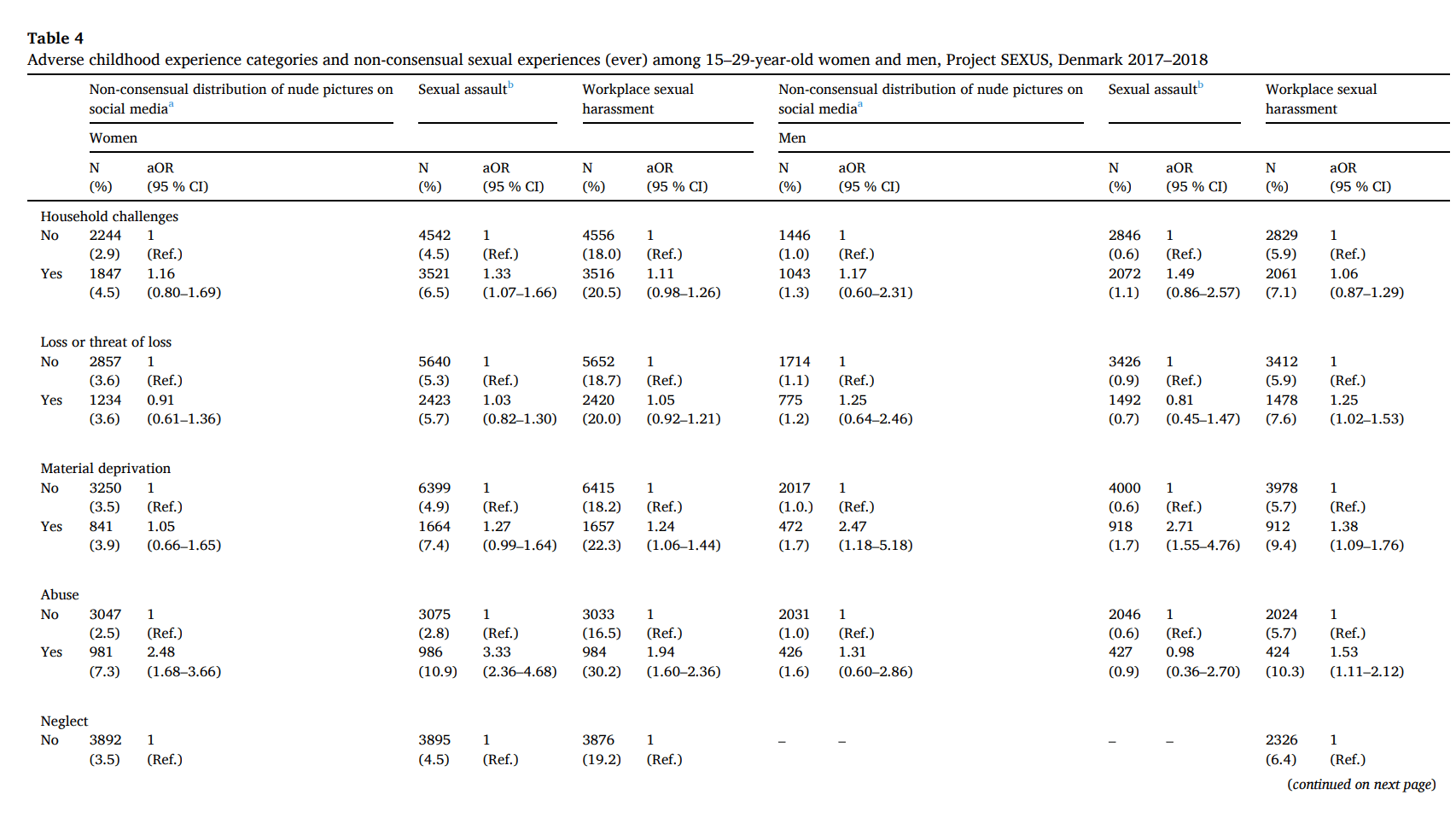

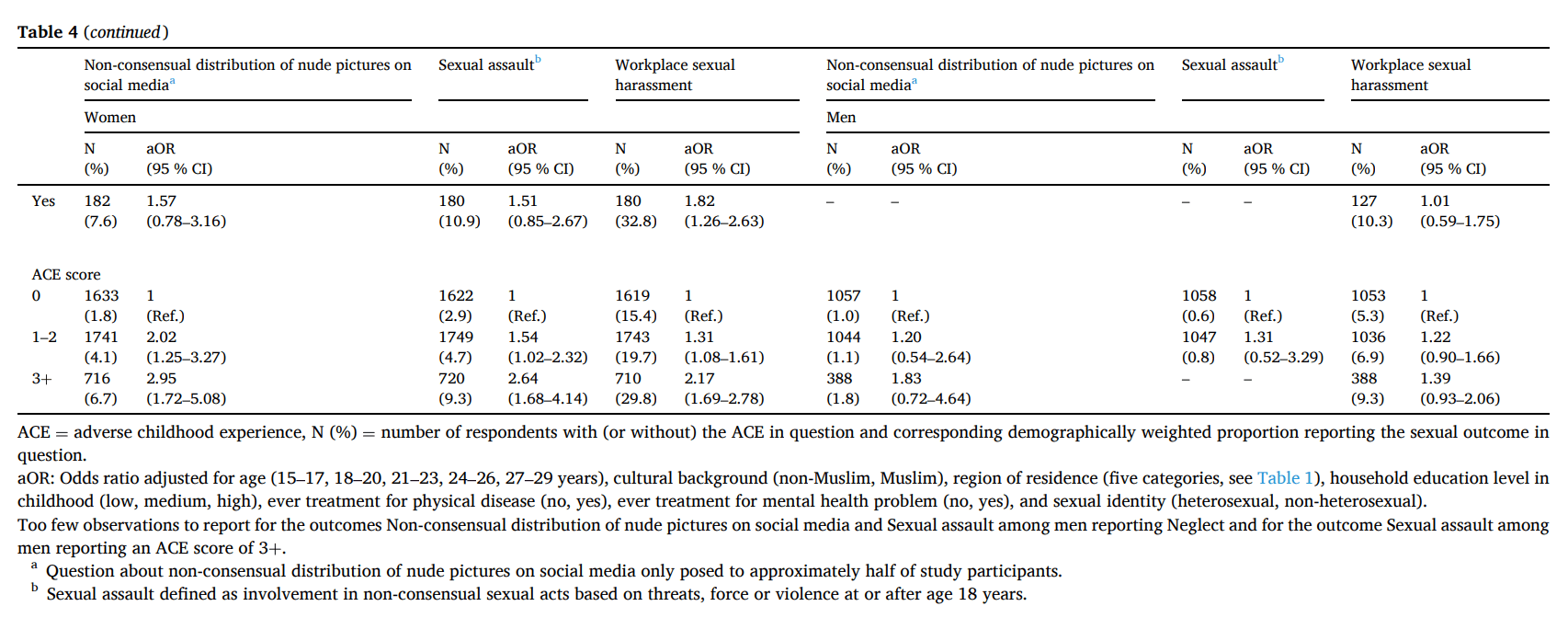

3.4. Associations of ACE categories with non-consensual sexual experiences

Compared with individuals of the same sex reporting no ACEs, non-consensual sexual experiences were reported more often by women with childhood experiences of Abuse or Neglect, women with ACE scores of 1–2 or 3+, and men reporting Material deprivation (Table 4). Workplace sexual harassment was the most commonly reported non-consensual sexual experience among both women and men, and such experiences were more common among women reporting Material deprivation (aOR 1.24; 95 % CI 1.06–1.44), Abuse (aOR 1.94; 95 % CI 1.60–2.36), Neglect (aOR 1.82; 95 % CI 1.26–2.63) or an ACE score of 3 or more (aOR 2.17; 95 % CI 1.69–2.78), and among men reporting Loss or threat of loss (aOR 1.25; 95 % CI 1.02–1.53), Material deprivation (aOR 1.38; 95 % CI 1.09–1.76) or Abuse (aOR 1.53; 95 % CI 1.11–2.12).

4. Discussion

In this large and nationally representative study of Danes aged 15 to 29 years, we confirm and expand prior reports of strong associations between ACEs and various measures of sexual risk-taking such as having had sexual intercourse before age 15 years and having had a high number of both recent and lifetime sex partners (Campbell et al., 2016; Felitti et al., 1998; Hillis et al., 2001; Hughes et al., 2017; Senn & Carey, 2010). Likewise, our findings corroborate observations by other researchers of higher rates of sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies among young people with a history of ACEs (Hillis, Anda, Felitti, Nordenberg and Marchbanks, 2000, Hillis, Anda, Felitti and Marchbanks, 2001, Hillis et al., 2004).

The observed links between ACEs and receiving payment for sex have not previously received much attention, although one study of 334 women of low socioeconomic status in the U.S. did find that women with a history of multiple ACEs reported transactional sex more often than women reporting no ACEs (Menza et al., 2020). In addition, we observed that men who reported Household challenges, Abuse or 3 or more ACEs were more likely to have received payment for sex or to have paid for sex themselves than men without such ACEs. As we analyzed data from a nationally representative cohort, our results were not limited to individuals of low socioeconomic position and they thus indicate that ACEs are associated with receiving payment for sex among both women and men and with paying for sex among men regardless of socioeconomic position. Our results revealed particularly strong associations of ACE categories Abuse and Neglect with sexual risk-taking behaviors, and ACE score analyses revealed a dose-response relationship between the number of ACEs experienced and all sexual risk-taking behaviors in women and several such behaviors in men. In line with our results, childhood abuse has previously been singled out as a potentially unique burden on children's development of health behaviors and their subsequent health in adulthood (Chartier et al., 2010). The cumulative effect of ACEs has also been identified in previous research showing that ACEs display a dose-response effect in increasing the prevalence of risky behaviors and poor health in general (Campbell et al., 2016; Chartier et al., 2010; Hillis et al., 2000). Our results add to this knowledge, showing that the cumulative effect of ACEs, and the particular burden of Abuse and Neglect, affect sexual risk-taking behaviors and consequently impact negatively on the sexual health of adolescents and young adults.

Around 40 % of our study participants, with or without a history of ACEs, reported unprotected sex within the last year with a person who was not their regular partner. Only one ACE category, Abuse, was significantly associated with this outcome. This result contrasts findings in a U.S. study of >88,000 9th and 11th grade students, which reported statistically significant links with unprotected sex for a range of ACEs, including household substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and psychological, physical, and sexual abuse (Song & Qian, 2020). We did, however, observe that individuals who reported ACEs more often had histories of sexually transmitted infections and, among women, of induced abortion of an unwanted pregnancy than peers without ACEs. Thus, the most obvious adverse consequences of unprotected sex were more commonly reported by individuals with ACEs. Unfortunately, we did not have information about the frequency of unsafe sexual encounters among study participants and, therefore, it is possible that young people with a history of ACEs engaged in such risky behaviors more often than peers without ACEs and, as a result, suffered the consequences of unprotected sex to a larger extent. Additionally, it is conceivable that young people with a history of ACEs may be less likely than peers without ACEs to take compensatory action, e.g., by seeking medical care or using emergency contraception after unprotected sexual encounters, thereby rendering them more prone to sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies.

We observed strong links between ACEs and non-consensual sexual experiences, especially among women. In line with our findings, a study of 1569 undergraduate students in the U.S showed that victims of childhood sexual abuse were likely to experience re-victimization later in life. Specifically, women with experiences of sexual victimization before age 14 years were at almost double risk of adolescent victimization compared with peers without such early experiences (Humphrey & White, 2000). The link between other ACEs and sexual victimization has received only limited attention. However, in one study of 7272 19–97-year-old individuals in the U.S., a range of ACEs, including sexual abuse, household challenges, emotional and physical neglect, and emotional and physical abuse, were all associated with an increased risk of adult sexual victimization (Ports et al., 2016), findings which align well with those of our current Danish findings.

Our study provides novel results on the association of ACEs with experiences of non-consensual distribution of nude pictures on social media, documenting an increased risk of such experiences among women reporting Abuse or an ACE score of 3 or more. The sharing and distribution of nude pictures on social media is a relatively new phenomenon, and the possible link with ACEs has been only scarcely studied. In a recent qualitative study of Danish students aged 15–27 years, non-consensual nude picture sharing most commonly afflicted girls, and female victims also received considerably more negative judgment than did male victims, suggesting that this kind of non-consensual sexual experiences may have quite different implications for girls and boys (Johansen et al., 2019). Our study confirmed that non-consensual distribution of nude pictures is a far more common experience among young women than young men. The observed strong link between ACEs and experiences of non-consensual picture sharing among women warrants consideration when planning preventive measures aimed at reducing violations of young people's digital integrity and rights.

4.1. Limitations

The ACE measures that we used captured adverse experiences through ages 0–17 years and were based on high-quality data from Danish national registers combined with self-reports of Abuse and Neglect, since data on the latter experiences were not available in national registers. It should be recognized, however, that we used a study-specific single-item question to assess Neglect, so cautious interpretation regarding that particular ACE is warranted. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that, for some of the youngest respondents, the reported sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences may have coincided with or even preceded the ACEs. Furthermore, some sexual outcomes were measured as “ever” experiences, why these could potentially also have overlapped with the assessment period for the ACEs studied. Consequently, while we consider the observed associations plausible and likely to reflect genuine associations between ACEs and subsequent sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences, these data limitations need to be carried in mind to avoid making too firm causal inferences.

Additionally, we were unable to differentiate between ACEs that took place in infancy, childhood, or adolescence as well as between ACEs that occurred only once and those that recurred or persisted throughout childhood and adolescence. Individuals growing up with ACEs occurring early in life or with repeated ACEs might plausibly exhibit stronger associations with several of the examined measures of sexual risk-taking than those with histories of later-occurring or fewer ACEs. Further characterization of such possible differences must await the availability of data resources with more detailed information about ACEs and an even larger study population than ours. Finally, it should be recalled that our study with its altogether five ACE categories and 10 sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experience outcomes across two sexes included a considerable number of statistical analyses. Consequently, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the statistically significant findings may have occurred by chance.

4.2. Conclusion

In this nationally representative study, we observed strong associations between a broad range of ACEs and sexual risk-taking and non-consensual sexual experiences among Danes aged 15–29 years. Especially childhood experiences of Abuse and Neglect were linked with sexual risk-taking in both women and men, and Abuse was also strongly associated with non-consensual sexual experiences in women. So far, public health interventions, such as campaigns aimed at increasing adolescents' awareness about sexually transmitted infections and how to navigate potentially harmful situations, have not been sufficiently effective, since risky sexual behaviors and non-consensual sexual experiences remain common. In light of our findings, future sexual health promotion among young people should be particularly attentive to the needs of individuals whose childhoods were burdened by ACEs.