Abstract

Developmental science demonstrates that important neurobiological development is ongoing throughout the teenage years and continuing into the mid 20s. As a result of neurobiological immaturity, teenagers continue to demonstrate difficulties in exercising self-restraint, controlling impulses, considering future consequences, and resisting the coercive influence of others.

ADOLESCENTS ENGAGE IN MORE RISKY DECISION MAKING

Adolescence has long been regarded as a period of decision-making that is different than adults and includes increased incidents of rash behavior. This account of adolescence is reinforced by empirical data surveying a range of behaviors, such as substance use (Johnston, Miech, Patrick, O’Malley, Schulenberg, & Bachman, 2023), reckless driving (Chein, Albert, O’Brien, Uckert, & Steinberg, 2011; Kirley, Robinson, Goodwin, Harmon, O’Brien, West, Harrell, Thomas, & Brookshire, 2023), unsafe sex (Committee on Adolescence, 2013; Herrick, Kuhns, Kinsky, Johnson, & Garofalo, 2013; Finer, 2010), and criminal activity (Brame, Turner, Paternoster, & Bushway, 2012; Loeber, Menting, Lynam, Moffitt, Stouthammer-Loeber, Stallings, Farrington, & Pardini, 2012; Shulman, Steinberg, & Piquero, 2013). The pattern observed across these diverse studies is one in which risky behavior becomes increasingly common during adolescence, peaks in late adolescence and then declines. This pattern also is reflected in the age-crime curve (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2019).

When combined with more fine-grained studies showing specifically how susceptibility to peer pressure, impulsivity, risk taking, and short-term thinking do not subside until later in young adulthood, it becomes impossible to reconcile the argument that 18 years old is a sensible age at which to expect people to “know better”/ be “responsible” (in a legal sense) with the observation that these indicators of impulsive, reckless, self-destructive, and antisocial tendencies peak at precisely this point. For example, in a study of over 1,000 participants ranging in age from 12 to 48 years, impulsivity declined, the ability to think long term increased, and individuals engaged in more responsible decision making as they transitioned out of adolescence and into adulthood (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000). In another study comparing adolescent and adult decision making, results indicated that, when asked to evaluate hypothetical decisions, adolescents as old as 18 years of age were less likely than adults (average age 23 years) to mention possible long term consequences, to evaluate both risks and benefits, and to examine possible alternative options (Halpern-Felsher & Cauffman, 2001). Furthermore, a study involving a gambling task with more than 900 individuals ages 10 to 30 found that late adolescents focus more on the potential rewards of a risky decision than the potential costs, whereas adults tend to consider both (Cauffman, et al., 2010). These empirical studies confirm that adolescents – even older adolescents – have not fully developed these abilities which may account for their poor decision making and immature judgment. In fact, data compiled across 28 different empirical studies demonstrate that adolescents generally perform more similarly to children than to adults when making decisions involving risk (Defoe, Dubas, Figner, van Aken, 2015). Additionally, some more recent work has shown that impulsivity is a feature of adolescence that spans across cultural and economic contexts (Steinberg et al., 2016) and can be linked to neurological and hormonal features during this developmental period (Braams, Peteres, Güroğlu, & Crone, 2014; Braams, van Duijvenvoorde, Peper, & Crone, 2015; Qu, Galvan, Fuligni, Lieberman, & Telzer, 2015).

A deeper body of empirical research on adolescent development and risk taking has accumulated over the past decade that significantly adds to the quantity and quality of existing scientific knowledge. A number of these new studies have already been cited. Others have made significant contributions to our understanding of the role of socio-emotional traits—such as sensation-seeking and self-regulation—in predicting adolescent risk taking (Burt, Sweeten, & Simons, 2014; Forrest, Hay, Widdowson, & Rocque, 2019; Fosco, Hawk, Colder, Meisel, & Lengua, 2019; Shulman, Harden, Chein, & Steinberg, 2015; Vazsonyi, Mikuška, & Kelley, 2017), the pervasive effect of peers in increasing risk behavior (Albert & Steinberg, 2011; Harakeh & de Boer, 2019; Centifanti, Modecki, MacLellan, & Gowling, 2014; Smith, Chein, & Steinberg, 2014), and the adaptive and intuitive nature of risk taking (Shulman & Cauffman, 2014; Tymula, Rosenberg Belmaker, Roy, Ruderman, Manson, Glimcher, & Levy, 2012). Additionally, in 2022, the Center for Law, Brain & Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital published a White Paper on the Science of Late Adolescence: A Guide for Judges, Attorneys and Policy Makers which detailed the findings in which scientists from various disciplines convened to discuss and integrate existing theory and emerging findings on adolescent risk behavior. In the report, they discuss the existing literature on adolescent brain development and the various individual (e.g., impulsivity) and environmental (e.g., deviant peers, school) risk factors that precede risk-taking behavior.

BRAIN DEVELOPMENT CONTINUES UNTIL AGE 25

What accounts for these differences between adolescents, including those in the transitional period between adolescence and adulthood, and adults with respect to risk-taking, planning, inhibiting impulses, and generating alternatives? Recent neurodevelopmental research demonstrates a biological dimension to adolescent behavioral immaturity: the human brain does not reach its mature, adult form until after the adolescent years have passed and a person has entered young adulthood (Gotgay et al., 2004; Somerville, 2016). As the American Psychological Association (APA) recently acknowledged, “there is no neuroscientific bright line regarding brain development that indicates the brains of 18- to 20-year-olds differ in any substantive way from those of 17-year-olds” (APA, 2022, p. 1).

Although the majority of brain growth occurs prior to adolescence, the brain continues to mature through at least age 20 (e.g., Bigler, 2021; Gur, 2021; McCaffrey & Reynolds, 2021; Somerville, 2016). There is considerable refinement within the brain that occurs across adolescence and through the transitional period in regions related to reward and risk—such as the prefrontal cortex, the nucleus accumbens, and the amygdala (Mills et al., 2014). In fact, the prefrontal cortex is among the last to develop which is important because it is like the CEO of the company. It is responsible for the evaluation of future consequences, the ability to weigh risks and rewards, and general decision-making processes (Bechara et al., 2000). In addition, this region of the brain is also essential for controlling emotions and inhibiting impulses (Casey et al., 2019).

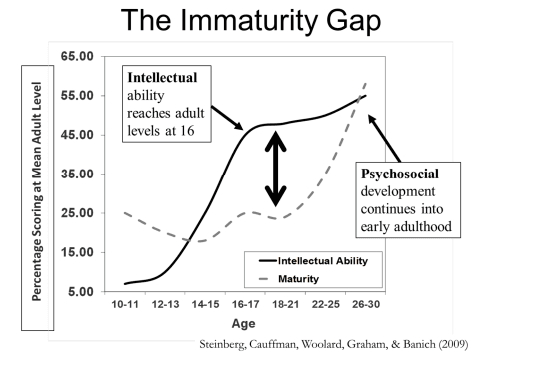

With the aid of advanced brain imaging technology and well-validated behavioral tasks, researchers are pinpointing the conditions under which adolescents’ decision-making differs from adults’ and illuminating the neurological developments that may correspond to these age differences. Synthesizing data from several lines of work, findings suggest that increased risktaking in adolescence results from asynchrony in the development of one’s psychosocial (e.g., self-regulatory system) and cognitive ability (e.g., intellectual ability). The psychosocial/self-regulatory system continues to develop at a steady pace from childhood into adulthood. The maturation of this psychosocial/self-regulatory system, which involves the prefrontal cortex and its connections with subcortical regions, is associated with improved impulse-control, harm-avoidance, and modulation of emotional and behavioral responses. In fact, research has shown that by age 16, adolescents’ general cognitive abilities are essentially indistinguishable from those of adults. Adolescents’ psychosocial functioning, however, even at the age of 17, is significantly less mature than that of individuals in their mid-20s (See Figure 1; Steinberg, Cauffman, Woolard, Graham, & Banich, 2009). As such, in situations that elicit impulsivity, that are typically characterized by high levels of emotional arousal or social coercion, or that do not encourage or permit consultation with an expert who is more knowledgeable or experienced, adolescents’ decision making is likely to be less mature than adults’.

FIGURE 1: Differences in the development of the psychosocial and cognitive (intellectual) systems

ADOLESCENTS ARE MORE SUSCEPTIBLE TO SOCIAL INFLUENCE AND THE BRAIN IS ESPECIALLY SENSITIVE TO SOCIAL INFLUENCE DURING ADOLESCENCE

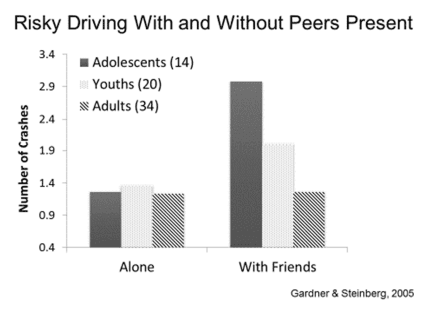

Peers have a particularly strong effect on adolescents. When in the presence of peers, adolescents’ appear to value more immediate rewards over long term benefits (O’Brien, Albert, Chein, & Steinberg, 2011). This bias toward short-term gains while in the presence of peers may lead adolescents to discount the potential consequences of risky decisions and may explain, to some degree, adolescents’ tendency to engage in risk taking. There is substantial psychological research illustrating this. For example, during a computerized driving task, adolescents who were randomly assigned to a condition of peer observation were found to take more risks (i.e., crash the car) than those adolescents who were assigned to perform the task alone (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005). Adult participants’ risk taking during the driving task did not significantly vary by condition (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005). Specifically, as shown in Figure 2, exposure to peers doubled the amount of risky behavior among mid-adolescents (with a mean age of 14), increased it by 50 percent among college undergraduates (with a mean age of 19), and had no impact at all among young adults (See Figure 2; Gardner & Steinberg, 2005).

FIGURE 2: Risky driving as assessed by number of times car crashes with and without peers present

A follow-up study was conducted using fMRI to measure participants’ brain activity during the same driving task under a solo condition and peer-observation condition (Chein et al., 2011). It is important to note that in the peer condition, the peer was not with the participant in the fMRI but rather watching the participant through the glass while the fMRI was being conducted. Findings indicated that the mere knowledge, and not actual presence, of your peer evaluating you increased risk taking among adolescents but not adults. Notably, when adolescents performed the task under peer conditions they demonstrated greater activation of brain regions related to reward during the decision making component of the task than was seen in the solo trials; in contrast, adults’ activation in these brain regions did not vary by social context (Chein et al., 2011).

These and other studies demonstrate that adolescents are more susceptible than adults to peer pressure and to the influence of others who are in positions of authority (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). It is thus not surprising that a disproportionate number of juvenile crimes occur when adolescents are in groups, or that teenagers are especially susceptible to pressure from somewhat older individuals to engage in antisocial activity (Braams, van Duijvenvoorde, Peper, & Crone, 2015; Shulman & Cauffman, 2014).

THE VAST MAJORITY OF ADOLESCENTS DESIST FROM CRIME BY AGE 25

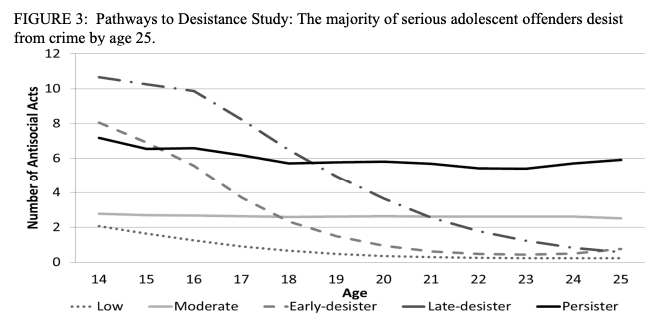

As adolescents transition to adulthood and their cognitive and psychosocial systems become fully mature, we would expect to see improvements in self-regulation and a gradual ceasing of engagement in criminal behavior. Thus, one way to consider the impact of this development on crime is through a study of why and when adolescents desist from (stop) criminal behavior. The Pathways to Desistance Study (Mulvey, Schubert, & Piquero, 2013) was designed for the express purpose of examining the second half of the age-crime curve: the desistance tail. Pathways, a prospective longitudinal study of over 1,300 serious adolescent offenders (e.g., offenses included robbery, aggravated assault, murder, etc.), tracked desistance from crime across adolescence and into adulthood. Youth who had committed serious felony level offenses were recruited for the study between the ages of 14-18 and were interviewed over 7 years, completing the study at ages 21-25 (see Schubert, Mulvey, Steinberg, Cauffman, Losoya, Hecker, & Knight, 2004 for details on the study’s methodology).

As illustrated in Figure 3, the Pathways study found that most youth, despite being serious felony offenders, do indeed desist from crime; less than 10% of the participating youth persisted in high-level offending after 7 years (see Figure 3; Monahan, Steinberg, Cauffman & Mulvey, 2013). This pattern has been replicated across fourteen other studies in addition to the Pathways study, providing strong evidence for a generally stable relationship between age and desistance (Doherty & Bersani, 2018).

Indeed, the major factor that distinguished those youth who persisted at a high level from those who desisted or remained at low levels was the increase in their psychosocial/self-regulatory development. Specifically, youth who persisted in offending displayed less psychosocial maturity (particularly lower levels of impulse control, suppression of aggression, and future orientation), while youth who stopped their criminal behavior displayed developmentally normative increases in these domains (Monahan, Steinberg, Cauffman, & Mulvey, 2013). This relationship between psychosocial maturity and desistance has also been replicated in other samples (Rocque, Posick, & White, 2015). In sum, the desistance tail of the age-crime curve may be largely (though certainly not wholly) explained by normative developmental changes that occur across adolescence and into adulthood.

It is important to highlight not only that there are changes in brain and personality with age but that the environment and life experiences can influence development. Life experiences, like the start of a new relationship or career, may place new demands on youth that result in long lasting brain and personality changes (Costa et al. 2019, Damian et al. 2019). These same experiences may act as turning points for serious criminal behavior, through which youth adopt new roles, responsibilities, and attitudes that lead them to desist from crime (Sampson & Laub 2005). For youth and young adults, it is essential that opportunities for different life experiences exist to promote psychosocial development.

DIVERSION IS RELATED TO LOWER RECIDIVISM AND BETTER OUTCOMES THAN FORMAL PROCESSING

A review of the literature suggests that diversion for low-to-moderately at-risk youth involved with the justice system is related to lower rates of recidivism than formal processing. Even when using the most conservative and statistically rigorous tests, almost all available evidence suggests that diversion is related to significantly reduced recidivism (at best) or no impact (at worse).

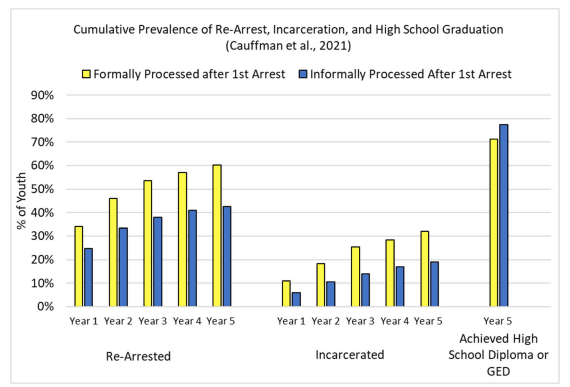

For example, in Crossroads, a longitudinal study of over 1,200 male youth found that informally processed youth (i.e., youth who were diverted from formal processing and handled at the probation department) were less likely than formally processed youth (i.e., youth whose cases were handled in the court) to be re-arrested, to be incarcerated, to engage in aggressive and violent offending, and to affiliate with delinquent peers up to 5 years after their first arrest (Cauffman et al., 2021). Specifically, over 60% of youth who were formally processed in adolescence were re-arrested within 5 years (compared to 43% of informally processed youth) and approximately 28% were incarcerated (compared to 17% of informally processed youth). In addition, informally processed youth were more likely to be enrolled in school, graduate from high school (or equivalent) within 5 years, and have higher perceptions of opportunities than formally processed youth. A lack of sufficient education is concerning as ample research shows that individuals without high school diplomas or equivalency are less likely to earn a livable wage and maintain stable, gainful employment (Bridgeland et al., 2006; Kienzl & Kena, 2006). Indeed, it is possible that justice system involvement is related to poor long-term occupational and economic outcomes because of the impact of the justice system on education attainment (see Figure 4; Cauffman et al., 2021).

FIGURE 4: Crossroads Study: Informal processing (diversion) leads to lower rates of incarceration/re-arrest and higher rates of high school completion/GED compared to formal processing.

In addition to processing type, sanction types and the way in which youth are treated by the justice system have been associated with recidivism (Gatti et al., 2009; Schubert et al., 2012). For example, the study by Gatti and colleagues (2009) found that youth who served time in secure placements (e.g., detention) had a higher likelihood of being arrested during adulthood than youth who served time on community supervision and youth who were never arrested (Gatti et al., 2009). Moreover, the climate inside secure facilities has also been related to reoffending. For example, Brown and colleagues (2019) examined the predictors of violence while incarcerated, and found that youth who perceived staff as fair were less likely to engage in institutional violence than youth who perceived staff as unfair (Brown et al., 2019). Furthermore, institutional climate has also been shown to influence youth behavior after release. One analysis with the Pathways data showed that youth who had more positive perceptions of their confinement experience were less likely to be re-arrested post-release, less likely to return to a secure facility, and exhibited lower self-reported offending in the year after being released (Schubert et al., 2012).

Other studies with Pathways and Crossroads data have demonstrated that some types of contact with the justice system (e.g., secure confinement) and exposure to serious violence may actually inhibit the development of psychosocial maturity during adolescence and early young adulthood (Dmitrieva et al., 2012). For example, youth who are incarcerated and embedded in harsh environments may be less likely to attain strong levels of psychosocial maturity by their mid-20s and may in turn fail to “age out” of the criminal behavior as they enter young adulthood (Dmitrieva et al., 2012). Thus, incarceration may actually delay normative development.

SUMMARY

In a summary of 20 years of research on adolescent and juvenile justice (Cauffman et al., 2024), it is clear that justice system responses need to take the developmental considerations described above into account. Specifically, although youth who commit crime should unquestionably face consequences for their offenses, the sanctions applied should be appropriate to the offender’s developmental status, amenability to future change, and degree of culpability (which may be lowered because of the diminished reasoning capacity implied by a lack of fully developed impulse control or ability to recognize long-term negative consequences of risky behavior). In addition, formal processing or incarceration as a means of deterrence or even rehabilitation is ineffective. In fact, more punitive sanctioning and incarceration can promote antisocial behavior and ensnare youth in trajectories of chronic offending (Cauffman, et. al 2021; Gatti et al. 2009). There are more effective alternatives to incarceration that address public safety concerns as well as serve the needs of the adolescent.