Abstract

This paper explores the policy debate in Queensland on raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR). The age currently remains at 10, despite reform in other Australian jurisdictions and recommendations to the contrary in a 2018 report from a highly regarded former Police Commissioner. In 2021, a parliamentary committee reviewed a private member’s Bill on the MACR and received 74 public submissions from over 300 individuals, all supporting raising the age. Despite this, the Bill was defeated. This paper reports on a content analysis and reflexive thematic analysis of those submissions to understand (a) the views of a broad range of Queensland organisations and individuals about the MACR and (b) their rationales for supporting raising the age. We found 13 such rationales, with a particular focus on the need for more extensive, appropriate and better integrated services for vulnerable children rather than punitive criminal justice responses, and a concern for worsening impacts on First Nations young people. These findings illustrate community support for both raising the MACR and adopting more evidence-based approaches to youth justice, accompanied by improved approaches to service support. We also briefly consider the counter-arguments against raising the MACR advanced in the Committee’s report.

Introduction – the Queensland context for ‘raising the age’

Like other jurisdictions in Australia and internationally, Queensland has seen calls for the raising of the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR). This issue gained ground with the Report on Youth Justice (Qld Government, 2018), delivered by former Police Commissioner Bob Atkinson. The report’s recommendations 68–70 set out an agenda for raising the age from 10 to 12 years, following a program of national cooperation, impact analysis and the establishment of needs-based programs and diversions for 8- to 11-year-old children engaged in offending behaviour (Qld Government, 2018, p. 106).

In its formal response to the report, the Queensland Government deferred the MACR issue pending a proposed national approach. In November 2018, the federal Council of Attorneys-General (CAG) established a working group to consider raising the MACR, with representation from the Commonwealth and all states and territories. A draft report was prepared in 2020 (CAG, 2020) but was not released publicly until December 2022 due to a lack of agreement to its contents by all jurisdictions (Dreyfus, 2022). When it was eventually released, the draft CAG report recommended that all Australian jurisdictions should raise the MACR to 14 years, although it also canvassed some alternative options (CAG, 2020, pp. 79–95). The draft report also stipulated matters for consideration prior to the implementation of the recommended change, which were similar in many respects to those raised in the Atkinson report.

Meanwhile, before the CAG report had been released, a private member’s Bill was introduced to Queensland’s Parliament to raise the MACR to 14 (the Criminal Law (Raising the Age of Responsibility) Amendment Bill 2021 Qld (the Bill)). The Bill was referred for consideration by a standing committee, the Community Support and Services Committee (the Committee). The Committee took submissions and held public hearings, reporting in March 2022. It recommended that the Bill not be passed, but instead that the government should pursue the Atkinson Report recommendation for a national agenda to raise the MACR to 12 years. A dissenting report noted that none of the 74 public submissions from over 300 individuals and/or organisations to the Committee had opposed raising the MACR.

The Bill failed to pass, but the submissions from groups and individuals from legal, health, social work, academic, religious and sporting backgrounds represent a rich source of data on first, public and community attitudes to this debate, and second, justifications for raising the age. In this paper, we report on a content and reflexive thematic analysis of these submissions, but before doing so briefly survey the broader policy context and the relevant literature to identify common rationales for MACR reform. Three of the authors of this paper were signatories to one of the submissions to the Committee, and the literature review that follows draws in part on that submission. In the second part of the paper, we use these rationales as the initial themes for our analysis of the committee submissions, while also inductively identifying further themes. In the third section of the paper, we summarise that analysis, before concluding with some brief implications arising from the paper. We also briefly consider the counter-arguments against raising the MACR advanced in the Committee’s report.

Literature and broader policy background

In this section, we summarise seven common rationales for why the MACR should be raised. These were developed by categorising the key arguments into the following: the requirements of international law, young people’s developing cognitive functioning and maturity, the impacts of trauma and deep disadvantage, the disproportionate effects of criminal justice contacts on First Nations young people, criminal justice impacts on recidivism, the costs of criminal justice responses, and the availability of alternative measures. We discuss each of these in turn, beginning by briefly describing legal and policy frameworks for MACR internationally and in Australia.

Legal and policy frameworks for MACR

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child came into force in 1990 and was ratified by Australia in that year. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) issues recommendations and guidance on implementing the convention. In its General Comment No.10 issued in 2007, the UNCRC recommended a global MACR of at least 12 years of age, without exceptions. In a 2019 update, General Comment No. 24 urges nations to increase their MACR to at least 14 years of age while commending States that have a higher minimum age, for instance 15 or 16 years of age (UNCRC, 2019).

The UNCRC observed that ‘the most common minimum age of criminal responsibility internationally is 14 years’ (UNCRC, 2019, p. 7), with that MACR common across Europe and OECD nations (see also Brown & Charles, 2021, p160; Qld Government, 2019, p. 104). In England and Wales the MACR is 10 years with the doli incapax presumption abolished (meaning all children over 10 are presumed to have capacity to commit crimes), in Canada, it is 12 years with no doli incapax, in New Zealand it is 14 years for most crimes, reducing to 12 or 10 for more serious offences (with doli incapax applying between 10 and 14 years so that the Crown must establish the individual child had capacity), while in 2019 Scotland increased its MACR to 12 years (see CAG, 2020, pp. 39–48; McAra & McVie, 2023).

Of the Australian jurisdictions, the Northern Territory was the first to raise its MACR, with legislation passed on 1 August 2023 setting the age at 12 (the Criminal Code Amendment Act 2022 (NT)) and retaining a simplified doli incapax for children aged 12–14. Children there aged 10 and 11 who engage in behaviour that could otherwise be an offence are instead to be referred to the Territory Families, Housing and Communities agency so necessary support services can be identified for them (NT Government, n.d.).

The ACT has also acted, passing the Age of Criminal Responsibility Legislation Amendment Act (ACT) in November 2023, which introduces a two-staged raising of the MACR to 12 upon the passing of the Act and then to 14 on 1 July 2025 (although children from 12 to 14 will still be able to be prosecuted for a few stipulated serious offences). The legislation also establishes a Therapeutic Support Panel for the support and treatment of children engaging in harmful behaviours. In April 2023 the Victorian government also committed to raising the MACR to 12 and then to 14 years by 2027 (Premier of Victoria, 2023). In December 2023 the Tasmanian government announced that state’s commitment to raise the MACR, and to increase the minimum age of detention to 16, as part of its Youth Justice Blueprint 2024-2034. That Blueprint incorporates a ‘therapeutic model of care for youth justice in Tasmania’ (Jaensch, 6 Dec, 2023), although details of what that will involve are yet to be released.

At the federal level and in other Australian states, the MACR remains at 10 years with doli incapax operating between 10 and 14 years. Australia has been consistently criticised by the UNCRC over the past 20 years for not raising its MACR (see CAG, 2020, p. 35). While some states and territories are moving to address this problem, others including Queensland, are lagging, despite well-established science and policy critiques, as discussed next. We classify these critiques as relating to (1) child development, disadvantage and trauma, (2) criminal justice impacts, and (3) evidence of better approaches.

Child development, disadvantage and trauma

Research shows that children develop capacity to understand the consequences of their actions gradually over adolescence and early adulthood, meaning they often over-estimate the benefits of their actions while under-estimating the costs to themselves and others (Benthin et al.,1993; Shulman et al.,2016). From middle childhood through adolescence, children are particularly susceptible to peer influence, while also being subject to the biological disturbances of puberty, which can result in increased levels of risk-taking behaviour (Andrews et al., 2021). The cerebral functioning which allows them to anticipate the consequences of their actions and regulate risk-taking impulses, does not fully develop until around the age of 25 (Cauffman et al., 2017; Lamb & Sim, 2013). Additionally, research has indicated that children in the youth justice system are significantly more likely than their peers to suffer from neurodevelopmental delays (such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder) and trauma (Bower et al., 2018). These developmental issues suggest that adolescents lack the capacity for criminal responsibility and that a therapeutic response may better address their offending.

Further, many young people who come into contact with the justice system are themselves victims of multiple disadvantages and trauma, including abuse and neglect, out-of-home care, domestic violence, social and educational exclusion, homelessness, physical and mental health problems, and for some, impaired cognitive development, all of which may further delay their development (Armytage & Ogloff, 2017; Widom, 2017). One study found 83% of children in custody in NSW had at least one psychological disorder and 17% had evidence of an intellectual disability (NSW Health & NSW Juvenile Justice, 2016), while others have shown the links between child maltreatment, domestic violence, mental health and juvenile offending (see Gilbert et al., 2020; Stewart et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2021). These types of adverse childhood events are highly prevalent among children who engage in behaviours that constitute offending (Singh, 2023).

Adverse experiences are particularly apparent for some First Nations young people, who are affected by the ongoing harms of colonisation (Smallwood et al., 2021). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are grossly over-represented in the youth justice system, particularly during the younger ages (AIHW, 2021; Ogilvie et al., 2022), which in turn intensifies over-representation in adult prisons (Stewart et al., 2021), with approximately 32% of Australian prisoners identified as First Nations (AIHW, Citation2023). In Queensland, most young people under youth justice supervision between the ages of 10 and 14 are Indigenous (AIHW, 2021) This may be due to a range of complex reasons including restrictive bail laws which impact unfairly on Indigenous youth, and the socio-economic and cultural disadvantage, systemic racism, trauma and grief, poor health and living conditions which are disproportionately experienced by First Nations people (Dellar et al., 2022; O’Brien, 2021). To this must be added the intergenerational effects of the incarceration of many Indigenous parents (Roettger et al., 2019) with around 31% of young people in Queensland’s justice system having a parent that has been held in adult custody (Qld Government, 2019).

Criminal justice effects

The direct detrimental effects on children of criminal justice contact, and especially detention, have been extensively documented and include the further entrenching of disadvantage, impact on family and community supports, impairment of educational and training outcomes, and increased likelihood of recidivism (see Armytage & Ogloff, 2017; Baldry et al., 2018; Clancey et al., 2020). The stigma of criminal justice contact can lead to young people having reduced opportunities for legitimate employment in early adult life and increased dependence on welfare and on stealing or drug dealing to survive (Rivenbark et al., 2018; Western et al., 2001). There is clear evidence suggesting that justice system contact promotes delinquency, which is partly explained by the criminogenic effects of labelling young people as offenders (Motz et al., 2020).

In addition to its recidivism effects, criminal justice responses to offending have led to increased government costs, even while crime is generally decreasing, with the costs of detention particularly high (Allard et al., 2020; Productivity Commission, 2024). To these direct costs must be added the indirect and life-long consequences for young people, for whom criminal justice contact often leads to disengagement from school and work, long-term health issues, and entrenched disadvantage (Cauffman et al., 2023; Productivity Commission, 2021).

Better alternative responses

Studies have identified better ways than through the criminal justice system, to address young people’s problem behaviours, including through early intervention, diversion and more joined-up services (Battams et al., 2021; Kuklinski et al., 2015; Motz et al., 2020; Oesterle et al., 2015; Welsh & Tremblay, 2021). Evidence is particularly strong for diversion of young people (Clancey et al., 2020; Pooley, 2020), which can also be designed to reduce First Nations over-representation (LSIC, 2018). However, researchers have noted the need for better multi-agency collaboration in identifying and supporting young people in need to facilitate these approaches (Battams et al., 2021; Homel, 2021). A further barrier to many such crime prevention initiatives is their short-term funding cycles (Battams et al., 2021).

Overall, the research evidence supports taking therapeutic rather than justice system responses to young people’s problem behaviour and offending. Raising the MACR is part of this approach, by firstly preventing children from having contact with the criminal justice system, but also ensuring children are older before they come into contact with the justice system. Specifically, the literature reviewed above identified seven key rationales for raising the MACR: the requirements of international law, young people’s developing cognitive functioning and maturity, the impacts of trauma and deep disadvantage, the disproportionate effects of criminal justice contacts on First Nations young people, criminal justice impacts on recidivism, the costs of criminal justice responses and the availability of alternative measures.

Methods

In this study we explore whether community views in Queensland accorded with the research by drawing on public submissions made to the parliamentary committee mentioned in the introduction. Our data comprised the complete pool of unique submissions. As all research material was publicly available no ethics approval was required. The Committee received a total of 75 unique1 public submissions on the Bill, representing more than 300 individuals and/or organisations. One submission was confidential and could not be reviewed. Therefore, we downloaded copies of all 74 unique publicly available submissions from the Parliamentary Committee’s website.2 We analysed these submissions to identify (a) their sources, (b) their key arguments and (c) the extent to which arguments/themes were consistent across community sectors.

Our analytic approach combined content analysis and reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2019). Content analysis was directed at systematically mapping the data to identify and quantify rationales for raising the MACR and whether this varied across different submission sources (Bengtsson, 2016), while the thematic analysis focused on identifying further themes in the data to those we had already noted in the literature, and understanding the context in which they were raised (Braun & Clarke, 2019). The analysis was an iterative process; first, we developed a coding scheme based on the aforementioned seven rationales for raising the age identified from the prior literature. Each submission was read and coded against the seven initial themes, while also capturing any emergent themes. During this process the themes were reviewed and reflexively refined, with submissions reread and discussed collectively until coding was agreed.

We also coded the source of the submissions into categories. Submissions could be coded in multiple ‘categories of sources’, for example, an organisation may be considered a community group as well as a First Nations organisation. The results of this, followed by the coding of the rationales for raising the MACR, is presented below.

Results

Sources of submissions

We categorised submissions via nine community segments based on their source (see Table 1). Most were from either community groups (36 submissions) or individuals (18 submissions representing nearly 250 individuals), with others from an array of government, academic, legal, health and cultural sources.

Table 1. Sources of submissions and the numbers of submissions emanating from each.

Categories of Sources | Number of submissionsa |

|---|---|

Community groups | 36 |

Individuals | 18b |

Legal organisations | 10 |

First Nations organisations | 6 |

Academics / researchers /universities | 5 |

Government agencies | 4 |

Health organisations | 3 |

Professional body | 2 |

Peak body | 2 |

a Total number exceeds 74 because submissions can be coded as originating from more than one source type.

b These 18 submissions represent nearly 250 individuals.

Rationales given for raising the MACR

In addition to the seven expected rationales already identified from the literature, six further themes emerged. Three related to the need for culturally competent; autonomous; and community-led responses to youth offending, reflecting the importance of these issues in the context of Queensland’s over-representation of First Nations people in the criminal justice system. The call for empowerment of communities resounded through a number of submissions and is exemplified in an academic submission that stated:

Funding for First Nations community-led solutions should be prioritised. … First Nations families and communities have the cultural knowledge and skills to inform this process for better outcomes for First Nations children. Therefore, they must be at the forefront of decisions in this regard. (Submission 70)

In addition, another academic submission highlighted the importance of supporting parents to support their children:

In my opinion these at-risk children do need to be insulated … this must not in any way resemble a forced removal from parental care. This is where indigenous led and culturally appropriate strategies developed with genuine indigenous consultation need to be designed, developed, and implemented. (Submission 74).

Finally, a community group submission highlighted the importance of addressing causes of offending and addressing intergenerational trauma while taking a community led approach:

I would like to emphasise that there needs to be further development of and sufficient treatment in culturally sound, community-based responses to intergenerational trauma impacts to better understand the root causes of offending in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people to facilitate positive outcomes for their future. (Submission 34)

A fourth emergent theme was identified in a submission from the Queensland African Communities (Submission 3) and that was the need for linguistic and cultural diversity more broadly. The other two emergent themes related to potential abuse of vulnerable detained children, and the problems of determining doli incapax, which both reflect more practical issues arising from the detention of young children. One legal service provider’s description of the application of doli incapax to children was highlighted in their submission in the following passage:

There is no evidence to support the argument that the doli incapax presumption provides a sufficient barrier to children aged 10–14 years. In fact, it can cause greater disadvantage to children when ‘highly prejudicial evidence’ which would ordinarily be inadmissible is relied on to rebut the presumption. YFS agrees with the findings in the Atkinson ‘Report on Youth Justice’ that doli incapax is ‘rarely a barrier to prosecution’. In YFS’ role as duty lawyer in children’s criminal matters, we see first-hand how easily the presumption of doli incapax is rebutted and young children are subjected to youth justice proceedings. (Submission 11)

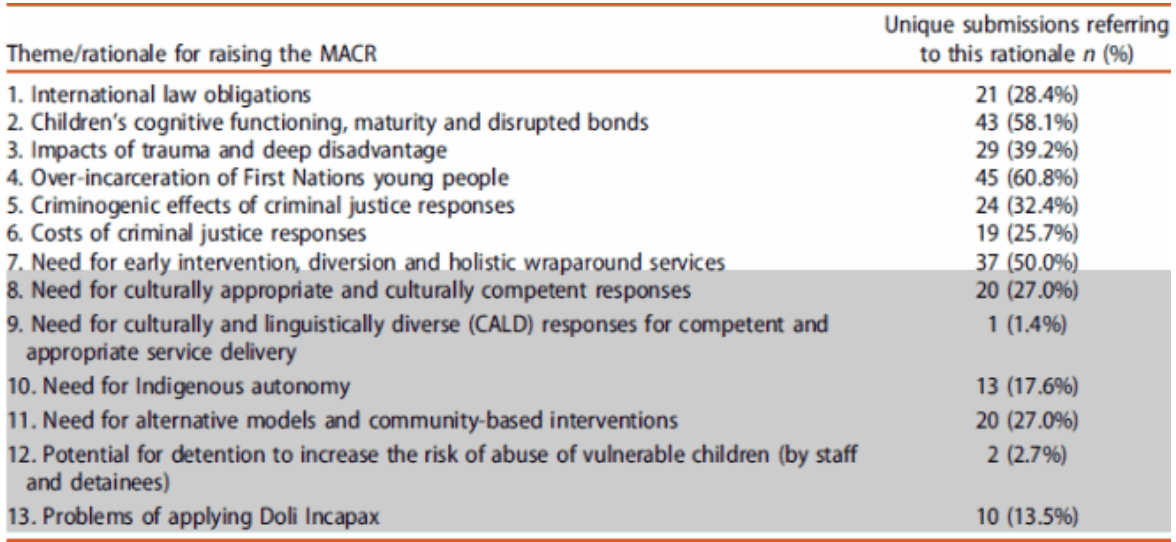

Once the final list of themes was identified, we then went through another iteration of coding of all submissions to capture all 13 themes, including the six emergent rationales. Table 2 contains the full list of the 13 themes identified from the submissions, as well as how frequently they were identified in the submissions in our final coding.

Table 2. Rationales identified in the 74 unique public submissions*.

Note: Most submissions mentioned multiple rationales for raising the MACR hence percentages total more than 100%. Percentages are calculated as a fraction of the 74 unique submissions.

* Shading indicates new themes emerging from thematic analysis of the submissions.

As shown, the most commonly raised themes were the initial seven drawn from the prior policy debates and academic literature. However, two of the emergent themes were each raised in 20 (27%) of the submissions, namely the need for culturally appropriate and competent responses, and alternative and community-based interventions to address young people’s behaviours. These themes relate specifically to the over-representation of First Nations young people in youth justice in Queensland but also other ethnic and cultural groups.

Did different community sectors raise different rationales?

As depicted in Table 3, peak and professional bodies focused mainly on themes relevant to their organisations. For example, the need for improved service delivery was common among service-providers. One submission from a flexi-school stated:

If the Government diverted the funds from pursuing 11-13-year old’s [using criminal justice approaches] to ensuring our schools had access to intervention and support programs we could make a difference to the number of youth offenders. (Submission 10)

They further provided a case study of a young person able to access their service to demonstrate its success:

In his time with The Centre Education Programme COD has been supported to establish trusting and secure relationships; improve his conflict resolution skills, take healthy risks, and understand the benefits of healthy living. This has been done in the context of a safe and welcoming environment, with a focus on positive reinforcement and ongoing encouragement. COD feels more capable of being proactive rather than reactive and is able to identify a clear pathway for himself moving forward. (Submission 10)

Additionally, the potential for abuse while incarcerated was raised by two organisations working with survivors. The need for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) responses was only mentioned in one submission by Queensland African Communities Council. It may be that the need for CALD responses is captured or implied in submissions regarding the preference for improved service delivery and culturally appropriate and culturally competent responses.

Overall, there was a high degree of homogeneity across the submissions, with particular agreement around themes 1 through 8. There was also strong support for the need for alternative models for children exhibiting problem behaviours, including in culturally appropriate ways. Many of the themes were captured in the proposal for a systemic way forward by the Youth Affairs Network:

If we are to gain broad support from the community for bringing an end to the shameful approach of incarcerating disadvantaged people, we need to demonstrate what can really reduce the engagement in criminal activity in the first place. This requires a total shift in policy and program design, development and implementation of a genuine whole of government children and youth strategy, significant redirection of investment into the primary prevention area and support for the Queensland youth sector to undertake the necessary work.

We propose a social health response focusing on supporting young people’s family and strengthening connection with their community and country.

A well designed and resourced Primary Crime Prevention Program which adopts a Community Development Model is the best way to facilitate this process. There is ample evidence available about the efficacy of Primary Crime Prevention and Community Development Programs. (Submission 30)

Discussion

Our content and reflexive thematic analysis sought to understand community views on the MACR in Queensland, and the extent to which those views reflect common rationales for raising the age. The submissions conformed with those rationales however, they also revealed the importance in Queensland of developing alternative responses to youth offending that address First Nations over-representation. Importantly, not all of those who made submissions are traditionally associated with the issue of youth justice. Many sources have broader functions relating to social welfare, health and the law, indicating that the issue of MACR also has resonance with and implications for these sectors.

The other main implication from our findings is the need for evidence-based alternatives to criminal justice responses, to accompany changes to the MACR. While as discussed earlier in our paper there is strong evidence for such approaches, approaches specific to First Nations children are understudied and unsatisfactory (McMahon et al. 2023). What is known is that it is important for First Nations youth well-being that programs be community-led (Cunneen et al., 2021).

Our other objective for this paper was to illuminate why, given the global trend towards raising the age, Queensland is lagging in doing so. This lag was exemplified by the Committee’s recommendation to reject the Bill, citing the government’s need for ‘more work' before raising the age (Qld Parliament, 2022). This work included implementing the outstanding Report on Youth Justice (Qld Government, 2018) recommendations, which calls for a national agreement on raising the MACR age, an impact analysis, and the introduction of needs-based programs and diversions. Balancing child welfare with community safety, underscored by the Queensland Police Union's submissions, was another primary concern cited in the Committee’s report (Qld Parliament, 2022). The dissenting report argued these reasons contradicted the evidence in the submissions, however in the next section we consider the rationales for rejecting the Bill.

Need for an impact analysis

The Committee recommended the completion of a comprehensive impact analysis as suggested in the Report on Youth Justice (Queensland Government, 2018), although neither that report nor the Committee detailed what this should entail. Recent impact analyses undertaken by Youth Justice are cost–benefit analyses (Deloitte Access Economics, 2019; Ernst & Young, 2020), while others in the academic literature also consider the long-term, downstream benefits to wellbeing and larger societal gains from policies that aim to delay or prevent children’s contact with tertiary (criminal justice) systems (Welsh & Farrington 2015).

Raising the MACR may not offer substantial direct cost savings, as daily rates for 10-13-year-olds in the youth justice system are stable at around 10% for all sanctions (Queensland Government Statisticians Office, 2021). However, true measurement of the impact of raising the MACR requires studies of the long-term effects across interconnected systems that support children. Evidence from jurisdictions like Scotland, which raised its MACR and reformed diversionary approaches, demonstrates delayed initial system contact and overall reduction in ongoing criminal justice system contact (McAra & McVie, 2018). Yet, there is inconsistency in these outcomes, stemming from fluctuating governmental and public stances on rehabilitation and broader system-wide strategies addressing the risks for youth antisocial behaviour (Haines & Case, 2018). As such, an impact analysis may not be sufficient to forecast the long-term benefits of adjusting the MACR. These benefits require well-designed longitudinal studies of individuals moving through multiple systems, whole-of-system approaches and sustained investment.

Establishment of needs-based programs and diversions

The Committee report also emphasised the importance of needs-based programs and diversions from the system in the ensuring the success of raising MACR. Many such needs-based programs already exist, as evidenced by the breadth of the submissions made. There are already diversions in place, such as restorative justice conferencing and after-hours co-responder models (Queensland Government, n.d.). As noted earlier, however, research suggests many such initiatives have insecure funding, limited availability and lack a strong evidence base (see Battams et al., 2021; Homel, 2021).

Often missing is an overall systematic approach to the targeted delivery of these services to those most in need. The MACR changes in other jurisdictions provide models for this. For example, the ACT legislation introduces a Therapeutic Support Panel, and Victoria has committed to a multi-stage support model. These models harness existing services to address problem behaviours of 10- and 11-year-olds to help avoid future justice contacts, followed by an alternate service model to ensure 12- and 13-year-olds receive services, to be designed by an Independent Review Panel (Premier of Victoria, April 2023). Importantly the response involves developing an Aboriginal Youth Justice strategy. These approaches are based on a model that appropriately funds existing services, and then develops a mechanism to ensure they are directed to those children that need them.