Abstract

The extent to which adolescents are influenced by their peers has been the focus of developmental psychological research for over 50 years. That research has yielded contradicting evidence and much debate. This study consists of a systematic review and meta-analysis, with the main aim of quantifying the effect of peer influence on adolescent substance use, as well as investigation into the factors that moderate this effect. Included studies needed to employ longitudinal designs, provide the necessary statistics to calculate cross-lagged regression coefficients controlling for target adolescent’s initial substance use, and comprise participants aged 10–19 years. A search of academic databases and reference lists generated 508 unique reports, which were screened using Covidence. The final inclusion criteria yielded a total of 99 effect sizes from 27 independent studies. A four-level meta-analytic approach with correction to allow the inclusion of multiple effect sizes from a given study was used to estimate an average effect size. Results revealed a significant effect of peer influence (β = .147, p < .001), indicating that adolescents changed their substance use behaviour in accordance with their peers’ perceived or actual use. Moderation analyses found peer influence effects varied significantly as a function of substance use behaviour (categorised as alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or composite substance use) and peer influence measure (perceived vs. actual peer report); however, no significant effects emerged in the multivariate moderation model simultaneously examining all five main moderators. These results suggest that adolescent substance use is affected by peer influence processes across multiple substance use behaviours and both directly and indirectly through perceived norms. This has significant implications for substance use prevention, including the potential of harnessing peer influence as a positive force and the need to target misperceptions of substance use.

Introduction

The extent to which adolescent substance use is influenced by that of their peers has been debated for decades. Although adolescent substance use has declined since 2001, many young people still engage in substance use behaviours that have potentially permanent negative consequences for their physical and psychosocial development (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2022). Especially concerning is the association between substance use and suicidal behaviour, considering both cannabis use and regular tobacco smoking may represent risk factors for the emergence of suicidality in adolescents (Serafini et al., 2012). It is therefore important to research and quantify the effect of different processes on adolescent substance use behaviour. The aim of this study is to synthesise the existing literature on peer influence on adolescent substance use and conduct meta-analyses to determine the magnitude of this effect and its moderators. Although previous systematic reviews have investigated the effect of peer influence on adolescents, these studies did not conduct meta-analyses (e.g., Henneberger et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2014), only assessed actual peer substance use (e.g., Giletta et al., 2021), or were limited to only one substance use behaviour (e.g., smoking in Liu et al., 2017; alcohol in Curcio et al., 2012). Additionally, no existing studies have looked at the moderating effect of perceived vs. actual peer measures, despite evidence suggesting that adolescents tend to be inaccurate when estimating their peers’ substance use behaviour (Trucco, 2020). The current study is significant in meeting this research gap as it aims to quantify the effect of peer influence across multiple substance use behaviours as well as investigating any differences between perceived peer substance use measures and survey data from actual peers.

Theoretical foundations

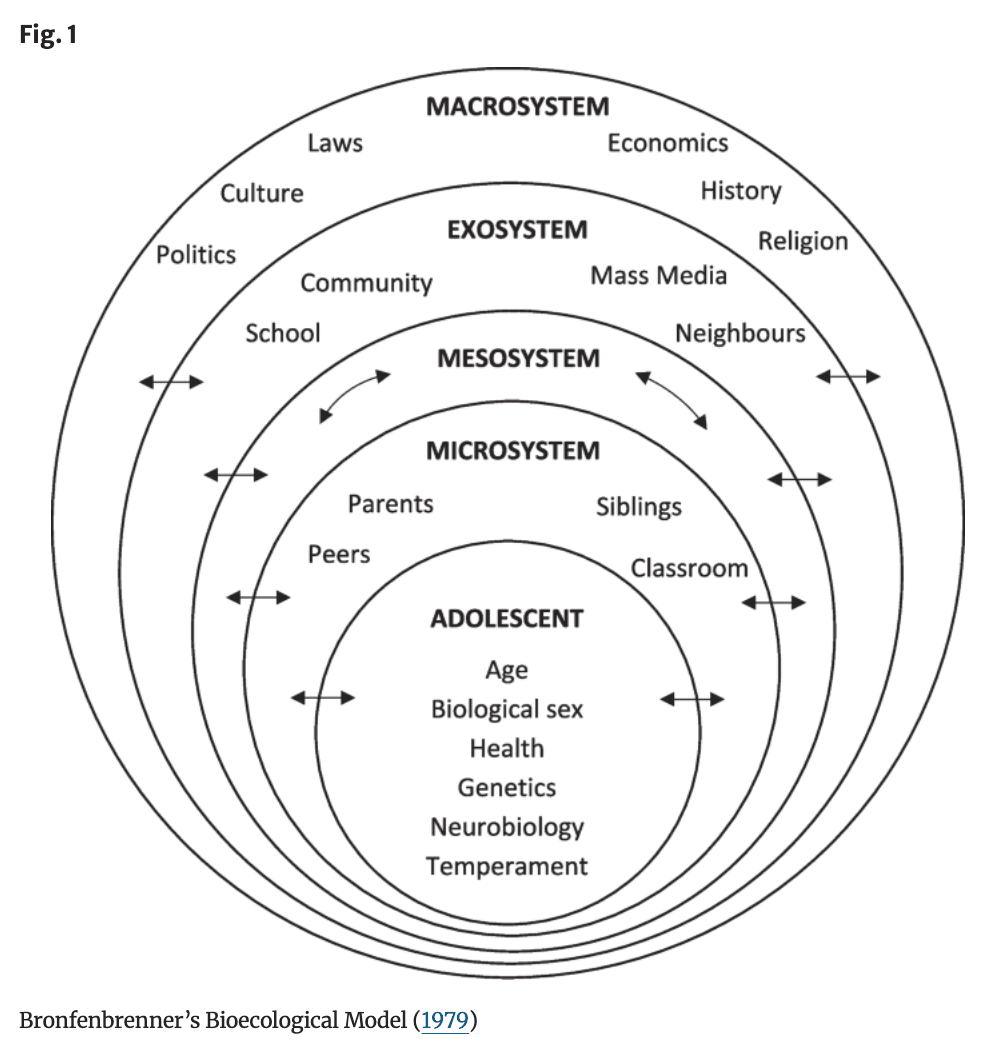

There are several theories that underpin peer influence effects, and it is important to consider substance use behaviour as having a complex aetiology. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model of Development (1979) suggests that adolescent development and health behaviour, including substance use behaviour, is shaped by multiple contextual factors arranged as socialisation systems surrounding the adolescent. Individual characteristics are at the centre of this model, and encompass innate factors such as biological sex, genetics, and temperament (e.g., inherited differences in emotional, attentional, and self-regulation processes; Trucco, 2020). These biologically based individual characteristics are considered the basis of susceptibility to the effects of the socialisation contexts.

Allen et al. (2022) reinforced the idea that adolescents are differentially influenced by their peers according to their genetics and traits, such as assertiveness and autonomy. Interestingly, they deemed peer influence processes as reflecting an overall adaptive developmental phenomenon, despite the potential negative effects, and suggested that it is the adolescent subculture promoting substance use behaviour that is problematic, rather than peer influence effects themselves. This was supported by the apparent influence processes being both neutral in valence and strongest for adolescents who were assessed as being the most well-adjusted, contrary to the common assumption that peer influence processes are reflective of poor functioning in the influenced youth (Allen et al., 2022). Bronfenbrenner (1979) elaborates on the socialisation contexts and classifies the concentric circles as the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem.

The most proximal system to the individual is the microsystem, which encompasses the immediate socialisation factors that affect the youth directly, including peers and parents. The next circle is the mesosystem, which represents the interactions between the individual’s microsystems, such as the connections between an adolescent’s parents and peers. The mesosystem is encircled by the exosystem, which consists of the larger social systems that operate indirectly with factors within the microsystem but have no direct effect on the individual (e.g., neighbourhood, school board). Lastly, the macrosystem is the outermost socialisation context which has a cascading function on development through the adolescent’s interactions across all settings. The macrosystem includes cultural values, religion, and laws, and, like the exosystem, it operates primarily through the more proximal factors. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model (1979) is a useful way to conceptualise adolescent substance use, as this behaviour does not occur in a vacuum. Rather, it is both directly and indirectly contributed to by multiple contextual factors with differential salience, with genetic and neurobiological differences affecting the individual’s sensitivity to different contexts (Trucco, 2020).

Another important theory to consider when studying peer influence is Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977), which posits that social environments affect behaviour through modelling. It proposes that adolescents develop cognitive representations about various attitudes and behaviours through observing influential social referents, and that these representations are invoked when making their own decisions about engaging in those behaviours. Bandura (1977) suggested that favourable attitudes towards substance use are likely to be reinforced when the adolescent perceives that the role model (a) is rewarded for enacting those behaviours, (b) is similar to the adolescent, and (c) has greater social status. These factors need to be taken into consideration as potential moderators of peer influence effects, as they are likely to contribute to the degree that an adolescent will change their substance use behaviour in accordance with their peer. Integrating Social Learning Theory and Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model is the Social Development Model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996), which posits that there are four contextual domains: family, school, peers, and religious and community institutions. Adolescents develop social bonds across these domains based on the perceived opportunities and rewards for involvement in either antisocial or prosocial activities. It follows that adolescents who anticipate social reward for prosocial behaviours will have a greater likelihood of engaging in these behaviours, as is true for antisocial actions. Additionally, the Social Development Model suggests that the salience of the socialising agents within the four domains will change as adolescents mature developmentally, with parents representing the main socialisation factor during childhood and early adolescence before shifting to a focus on peers in middle and late adolescence (Trucco, 2020).

Peer socialisation context

Concentrating on the peer context domain in the Social Development Model, peer influence is thought to operate through direct and indirect socialisation mechanisms. As an overarching concept, peer influence is defined as the social processes by which people change their attitudes and behaviours to conform to that of their friends (Barnett et al., 2022; DeLay et al., 2023; Leung et al., 2014). Peer influence processes can have both positive and negative outcomes, with adolescents describing socialisation pressure to engage in prosocial behaviours as well as antisocial behaviours (Adikini, 2023; Bartolo et al., 2023; Trucco, 2020; Zedaker et al., 2023). De la Haye et al. (2013) suggest that friendships can have a protective effect if friends do not endorse marijuana using behaviours. This finding aligns in with the concept of peer norms, which suggests that the perception of peer approval of a behaviour promotes that behaviour (Trucco, 2020). While the idea of adolescents being convinced to engage in substance use behaviour by coercive and pressuring peers is popular, it is likely that adolescents are more influenced by support and validation than directly by pressuring behaviour (Allen et al., 2022). This is one reason why interventions focused on helping adolescents resist peer pressure are often not effective; only a small part of peer influence may be active persuasion, while most of the effect is contributed to by perception of group norms, social acceptance, and status (Leung et al., 2014). Additionally, it is difficult to disentangle peer selection and peer socialisation processes. Peer selection is consistent with the theory of homophily; i.e., that individuals choose friends who are closely matched to their own attitudes and behaviours (Trucco, 2020). Peer selection processes are also invoked by social identity theory, which states that a fundamental aspect of psychosocial identity development is making judgements about the groups you belong to. Conversely, peer socialisation describes an individual’s decision to modify their attitudes and behaviours to adapt to social norms (Trucco, 2020). This distinction represents a challenge in research on peer influence, as these distinct processes of peer selection (i.e., adolescent’s own substance use behaviour promotes selection of friends who use substances) and peer socialisation (i.e., peer group’s substance use behaviour contributes to the adolescent’s use) appear the same in cross-sectional designs. Longitudinal studies are essential to separate the two processes, but it must also be considered that they can operate together and bi-directionally (Leung et al., 2014). This results in a reinforcing cycle in which substance using adolescents select peers with similar substance use levels, which promotes normative expectations about substance use that influence other adolescents.

Adolescence

Adolescence is a developmental period characterised by significant psychosocial, cognitive, moral, and physical development (Allen et al., 2012). Research suggests that there is a normative increase in deviant behaviour in adolescence, with substance use typically initiated during this period (Veenstra and Laninga-Wijnen, 2022). The World Health Organisation (2021)defines adolescence as the ages between 10 and 19 years, with pubertal onset typically beginning by age 9 to 12 years. The transition from childhood to adolescence is characterised by an increased focus on peer association and acceptance, which is a shift from parents as the primary socialisation factor to peers (Leung et al., 2014). Adolescents are more likely to seek peer approval and internalise the views of their peers, which, when combined with heightened sensitivity to social reward and increased engagement in novel experiences, promotes conforming to perceived group norms.

Aims

The main aim of this study is to quantify the effect that peer influence has on adolescent substance use. The hypothesis is that both actual and perceived peer substance use for alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and composite substance use will significantly predict change in target adolescents' own substance use over time. Additionally, we predict that perceived substance use will have a greater effect size, as adolescents tend to erroneously overestimate their peers’ substance use behaviour (Helms et al., 2014). Although we predict that peer influence effects will be significant for all substance use behaviours, we hypothesise that alcohol and composite substance use will have the largest average effect sizes. This is because alcohol is the most normalised substance and has the highest proportion of participants partaking, with only 34% of high school students aged 14–17 never having consumed alcohol (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2022; Trucco, 2020). Conversely, the same 2017 survey found that 82% of adolescents aged 12–17 years had never smoked tobacco, and 16% had used cannabis (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2022). This suggests that alcohol and composite substance use will have the largest and most robust effect sizes, predominantly due to the greater proportion of adolescents engaging in that behaviour, with cannabis next and tobacco having the smallest effect. Age is hypothesised to be a moderating factor, with research suggesting both linear and curvilinear effects (Trucco, 2020). Regarding linear effects, we hypothesise that overall substance use will increase with age; however, a curvilinear pattern is hypothesised to emerge, where peer influence peaks in early adolescence (approximately 12–14 years; Giletta et al., 2021). It is hypothesised that time lag between waves in the longitudinal studies will have a moderating effect on peer influence, with shorter time lags being associated with larger effect sizes. Lastly, gender is not expected to be a significant moderating factor. This is not necessarily because there is not a difference in peer influence as a function of gender, rather that opposite effects are commonly found across studies, so we expect that they will mask any real effects that may exist (Leung et al., 2014) (Fig. 1).

Methods Search Procedures

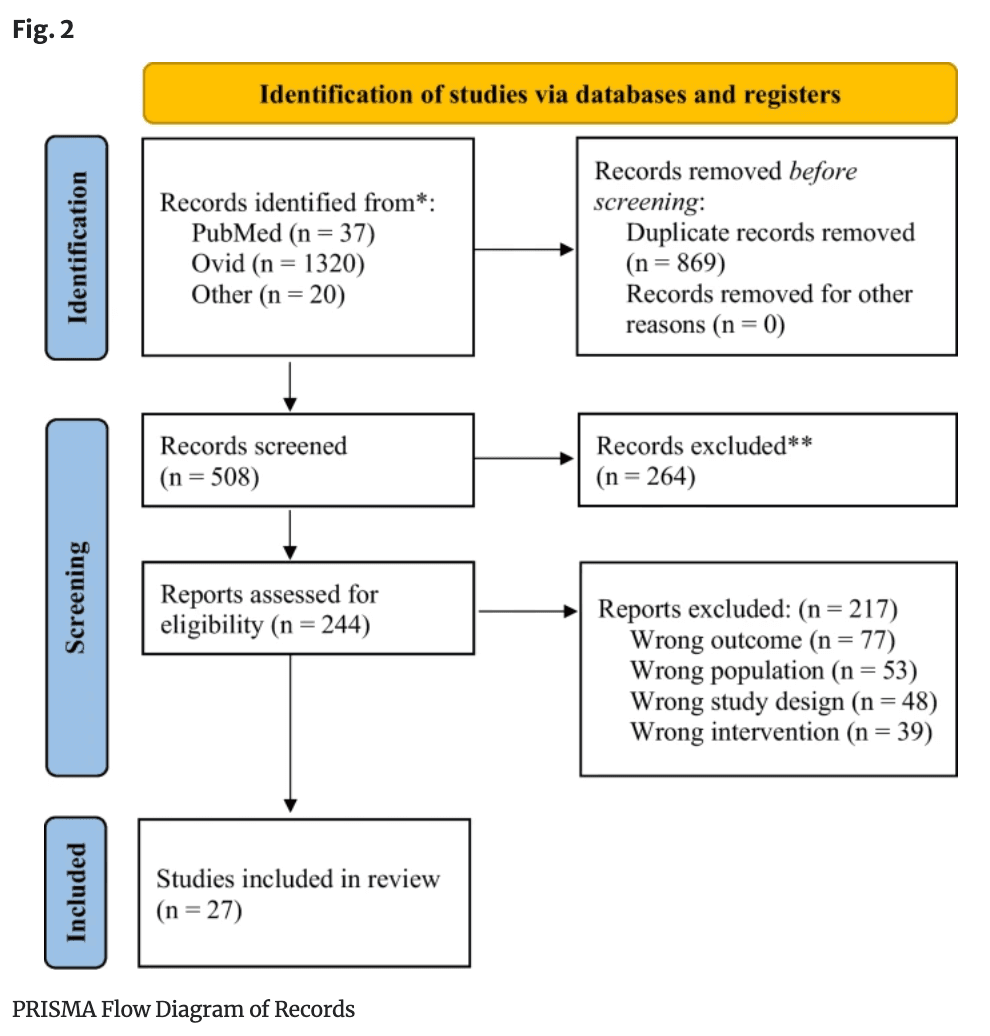

This literature review consisted of five stages: (1) research question development and operational definitions, (2) database search, (3) study screening and evaluation using Covidence, (4) data extraction into IBM SPSS Statistics, and (5) data analysis with R. Eligible studies were identified through electronic searches of the databases Ovid (PsychInfo and PsychArticles) and PubMed. To yield the largest amount of returned results, the literature search used keywords from the following three groups to capture substance use, adolescents and peer influence: ‘drug addiction / drug abuse / substance abuse / substance addiction’ AND ‘adolescents / teenagers / young adults / teen / youth / student / adolescence’ AND ‘peer influence / peer influence on adolescent substance abuse’. The search was restricted to peer reviewed journals published in English between 1972 and 2022. Additional records (n = 20; see Fig. 2) were identified using a ‘snowball’ search of reference lists of included articles and systematic reviews on similar topics. As seen in Fig. 2, these searches yielded 508 unique reports that were first screened for eligibility through examination of titles and abstracts, before evaluating the full texts for suitability.

Selection Criteria

Considering that the aim of this meta-analysis was to quantify the degree that peers influence adolescents’ substance use, only studies that used a prospective longitudinal design were included. While cross-sectional designs are commonly used in studies examining peer influence, it is impossible to differentiate between peer selection and peer influence effects. Concurrent associations between peer and target adolescent substance use in cross-sectional designs could be a result of peer influence processes; however, it is possible that behavioural similarity preceded the peer relationship and contributed to its formation. Longitudinal designs enable the observation of substance use change over time in accordance with peer use, while controlling for past behaviour and potential moderators. Although the processes of peer influence are too complex to establish direct causal relationships, longitudinal survey data can reflect influence as it exists in everyday interactions over time, which provides ecological validity (Giletta et al., 2021). Longitudinal studies that collected data from at least two time points, with both peer and target substance use assessed simultaneously at an initial time point, were included. The decision to take a cross-lagged regression approach whereby effect sizes are computed from three correlation coefficients across any two assessments in a longitudinal study (see Effect Size Calculation), is consistent with previous meta-analyses in peer influence (e.g., Giletta et al., 2021). Only empirical studies collecting quantitative survey data were included, with qualitive methods and reviews excluded. Additionally, studies incorporating interventions or experimental manipulations were excluded, as were studies examining populations in clinical settings. This exclusion criterion was chosen because intervention programs and atypical contexts may have significant effects on peer influence. Studies were included if the outcomes measured substance use as alcohol, tobacco, and/or marijuana, with studies that didn’t differentiate being classified as ‘composite substance use’. The population was limited to participants aged between 10 and 19 years, as this is the age group defined as adolescence (World Health Organisation, 2021). Studies were included if they provided the required statistics to compute three zero-order correlations, standardised estimates from linear regression models adjusting for previous substance use, or path analyses using a longitudinal actor-partner interdependence model (APIM).

Effect Size Calculation

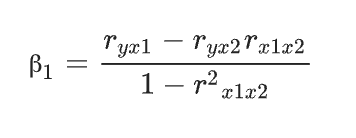

In Becker’s Eq. (1992), ββ1signifies the standardised regression weight of X1 (i.e., peer substance use at Time 1) predicting Y (i.e., target adolescent’s substance use at Time 2), while controlling for X2 (i.e., target’s substance use at Time 1).

Data Analysis

Of the 27 studies included in the meta-analysis (see Table 1), 16 studies (60%) could extract multiple effect sizes, so a multilevel approach with the robust variance estimation (RVE) technique was used (Hedges et al., 2010; Tipton, 2015). Multiple effect sizes could be calculated either in studies that used multiple time points (i.e., cross-lagged correlation coefficient for correlations between Time 1 to Time 2, Time 2 to Time 3, and Time 1 to Time 3) or multiple substance use behaviours (i.e., separate measures for alcohol and tobacco). This means that these effect sizes are nested within the studies and are not independent, thus violating assumptions of traditional meta-analytic approaches (i.e., random effects and fixed effects models). RVE provides a way to maximise data in a meta-analysis when the assumption of independence is violated by correcting the standard errors (Pustejovsky & Tipton, 2022). Several meta-analyses have found that the RVE method applied a posteriori yields confidence intervals with acceptable Type I error rates even if the form of the dependence is unknown (Fernández-Castilla et al., 2021; Giletta et al., 2021; Pustejovsky & Tipton, 2022). Statistical analyses for the mean effect size and moderating effects were based on RVE, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and Satterthwaite approximation used to find the effective degrees of freedom in the t-statistics.

The combination of RVE and a four-level random-effects regression model explicitly accounts for the potential dependencies among the multiple effect sizes (Giletta et al., 2021). Level 1, random sampling variance, is also included in traditional random-effects meta-analyses and describes the variation of the observed effect size around the ‘true’ effect size, as a function of sample size. Level 2 represents within-study within-wave variance (e.g., effect sizes for both alcohol and tobacco use measured in the same study from Time 1 to Time 2). Level 3 reflects within-study between-wave variance (e.g., effect sizes for alcohol use measured in the same study from Time 1 to Time 2, Time 2 to Time 3, and Time 1 to Time 3). Lastly, Level 4 is between-study variance (e.g., variation between effect sizes from different studies).

First, the weighted-mean effect size of peer influence effects was estimated from an unconditional four-level random-effects model with RVE correction. Heterogeneity in the effect sizes was examined, with attention to the distribution of the total variance across the four levels. The median sampling variance was used in heterogeneity calculations. Next, each moderator (i.e., substance use behaviour, peer influence measure, mean age at baseline, time lag, and gender) was analysed separately as a predictor in the four-level model. Finally, a multivariate conditional model analysing the effects of the main five moderators simultaneously was conducted. This was to account for possible correlation between moderators (e.g., older adolescents reporting greater substance use) masking effects or yielding illegitimate results.

The meta-analyses were conducted in R for Mac (Version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022). The metafor package (Viechtbauer, 2010) was used to estimate multilevel metaregression models, using the restricted maximum likelihood method (REML) with effect sizes weighted by inverse sampling variance (Giletta et al., 2021). RVE correction was applied using the packages clubSandwich (Pustejovsky, 2018) and robumeta (Fisher et al., 2017).

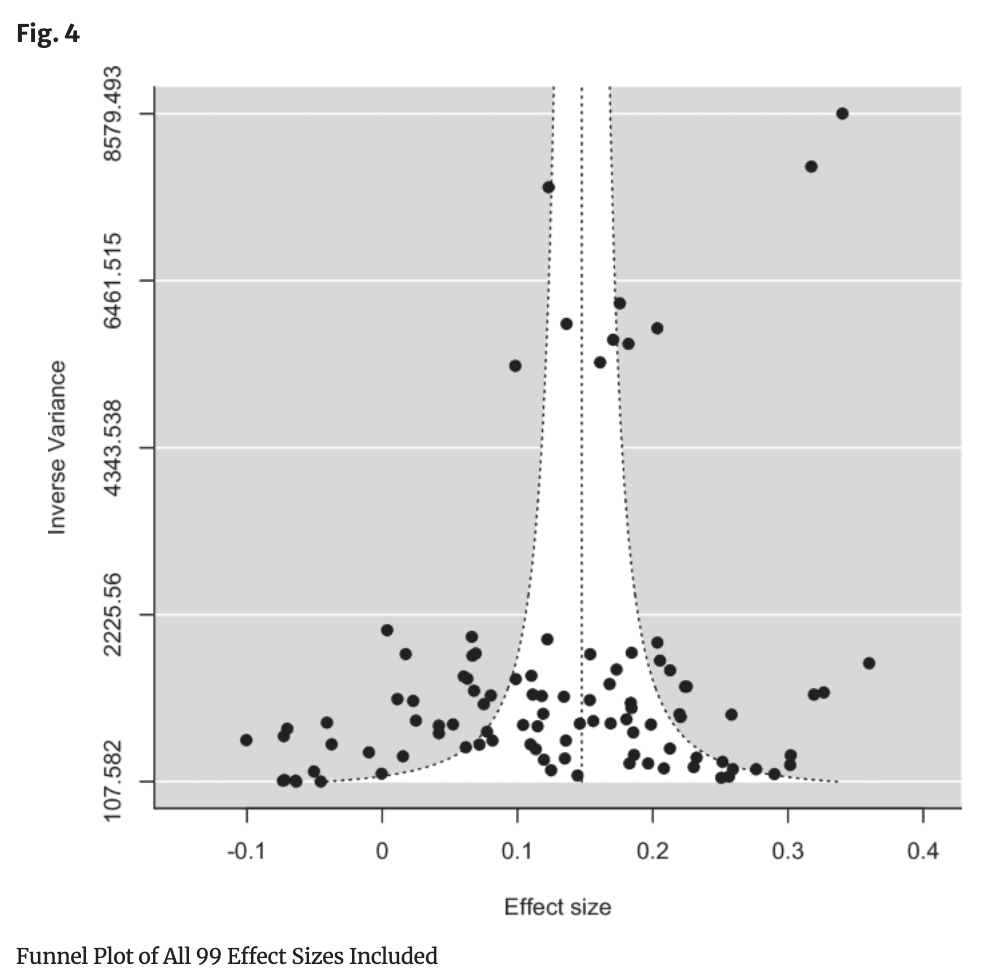

Publication bias was examined in two ways: visual inspection of a funnel plot and moderation analyses of the inverse sampling variance. Funnel plots are a scatterplot with the inverse variance on the y-axis and the effect size on the x-axis. In the absence of publication bias, the studies form a symmetrical funnel shape, with the assumption that studies will scatter centrally around the total overall estimated effect. Asymmetry in the funnel plot suggests that studies with non-significant or negative results were not published, although it could also indicate inadequate screening in the systematic review or reporting bias. As visual inspection might be subjective, it is not considered a reliable method of estimating publication bias (Liu et al., 2017). As a more robust measure, moderation analyses of the inverse sampling variance were conducted. Publication bias is suggested by a significant association between inverse variance and effect sizes, with the assumption that small effect sizes with small inverse variances are less likely to be reported. If publication bias is detected, the validity of the current study’s results is threatened, as the results of the meta-analysis may not represent the reality of peer influence processes.

Results

Sample Characteristics

This systematic review identified 27 independent studies, yielding 99 effect sizes, dating from 1978 to 2022 (Mdn = 2008). Included studies were conducted in five different countries, most in the USA (n = 22), followed by the Netherlands (n = 3), Sweden (n = 1), Australia (n = 1) and China (n = 1). A total number of 28,325 participants (M = 44% boys) were included in the meta-analysis, with sample sizes differing from 126 to 7,108 participants across studies. Participants’ mean age at baseline ranged from 10.50 to 16 years (M = 13.73, SD = 1.41). The average length of time between follow-up assessment in consecutive waves of the longitudinal studies was 15.25 months (SD = 16.45, Mdn = 12 months, range = 6–96 months), with a majority of studies assessing peer influence over a 12-month period (68.8%). Substance use behaviour was classified according to the substance investigated, which comprised alcohol (n = 43), tobacco (n = 26) and marijuana (n = 3). Studies that did not distinguish between different substances (e.g., asked participants how often they used drugs and alcohol), were classified as composite substance use (n = 27). One of the aims of this meta-analysis was to quantify any significant differences between studies that used the target adolescent’s perception of their peers’ substance use and studies that used survey data from actual peers. Across the 99 effect sizes included, 54 used perceived measures of peer substance use (54.5%) and 45 used actual peer measures (45.5%). See Appendix A for a summary of the main descriptive characteristics of the studies included in this review.

Weighted-Mean Effect Size and Heterogeneity

For the total sample of 99 effect sizes, cross-lagged effects of peers' substance use on subsequent target adolescents' use controlling for initial similarity ranged from -0.10 for tobacco to 0.36 for composite use (i.e., alcohol and/or tobacco and/or marijuana), which is displayed in Fig. 3. The multivariate meta-regression model with RVE correction to allow for multiple potentially dependent effect sizes from the same study generated a significant weighted mean cross-legged regression coefficient, ββ¯= 0.147 (SE = 0.016, 95% CI [0.115, 0.180], p < 0.001). This result indicates that adolescents changed their substance use behaviour over time in the direction of their peers’ actual or perceived substance use.

Examining heterogeneity in the effect sizes revealed significant variation. The median sampling variance was 0.001 and represented 11.24% of the total variance. The Level 2 variance, 0.003, χ2(1) = 61.91, p < 0.001, represented 28.43% of the total variance, indicating that within-study within-wave variance (i.e., differences in effect sizes between the same wave of a particular study) were larger than expected due to sampling variability alone. The Level 3 variance, 0.001, χ2(1) = 1.76, p = 0.18, represented 11.42% of the total variance, although it was not significant, meaning that within-study between-wave variance (i.e., differences in effect sizes between different waves of a given study) was within the range expected by random variance. The Level 4 variance, 0.005, χ2(1) = 12.84, p < 0.001, represented 48.92% of the total variance, indicating significant between-study variance (i.e., differences in effect sizes between different studies). Heterogeneity at both the within-study within-wave and between-study levels suggests that there are likely moderators of the effects observed, which will be explored in subsequent moderator analyses.

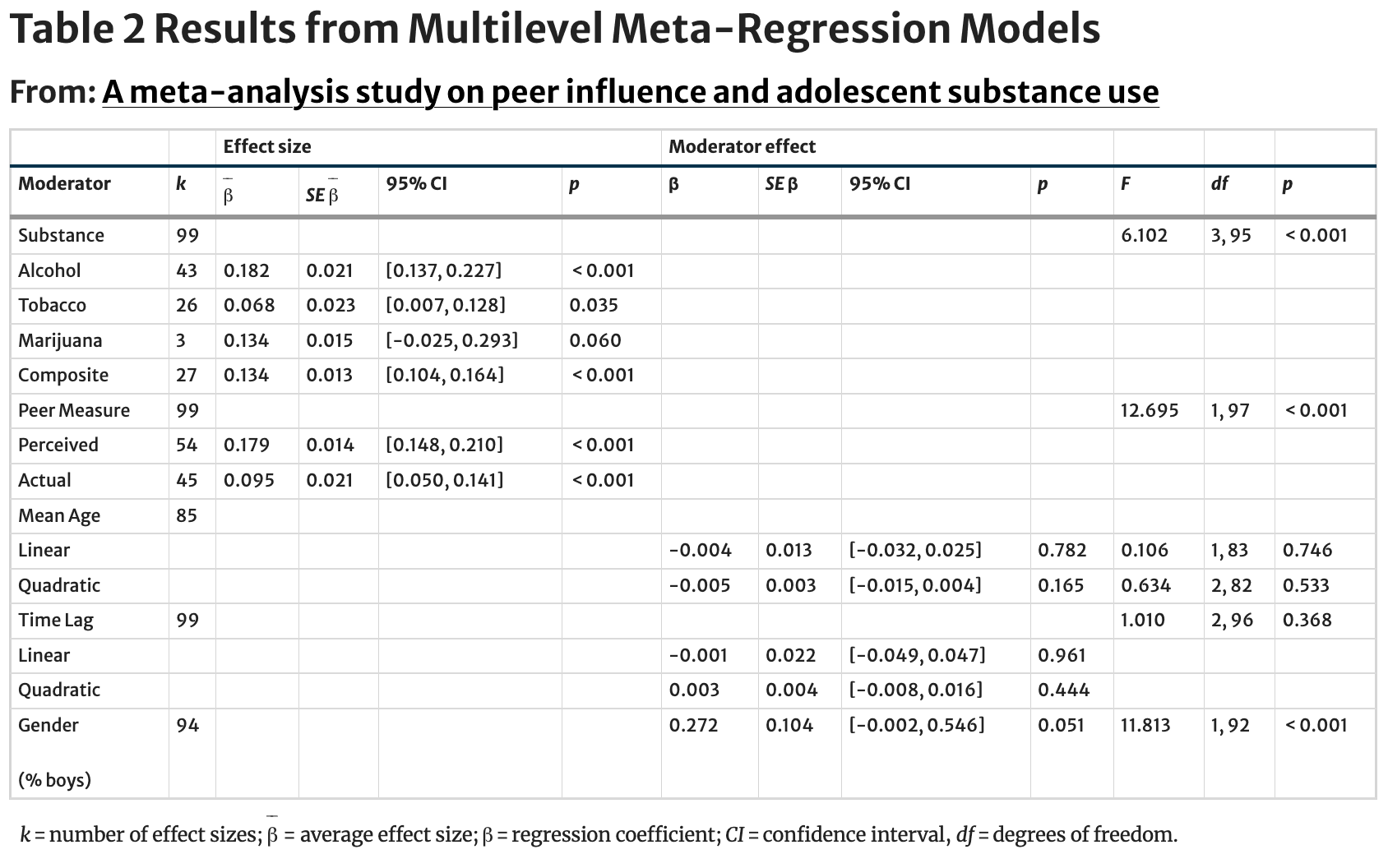

Moderator Analyses Substance Use Behaviour

Moderator analyses were conducted to explain the effect size heterogeneity. First, substance use behaviour was examined to determine whether the specific substance, categorised as alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or composite substance use in cases that didn’t differentiate between substances, might affect the magnitude of peer influence processes. Moderation analyses revealed significant differences between the substance use behaviours, F(3, 95) = 6.102, p < 0.001 (see Table 2). The average cross-lagged correlation coefficient was significant for alcohol (k = 43, ββ¯= 0.182, SE = 0.021, 95% CI [0.137, 0.227], p < 0.001), tobacco (k = 26, ββ¯= 0.068, SE = 0.023, 95% CI [0.007, 0.128,, p = 0.035), and composite substance use (k = 27, ββ¯= 0.134, SE = 0.013, 95% CI [0.104, 0.164], p < 0.001).

Peer Influence Measure

Substantial research on peer influence has established that, consistent with social norm theories, perceived substance use, acceptance or approval is associated with adopting substance use behaviours (Trucco, 2020). This is especially problematic considering that adolescents tend to overestimate peers’ engagement in substance use, with the size of these misperceptions amounting to large effect sizes (Trucco, 2020). This meta-analysis sought to determine whether there is a significant difference between studies that used perceived measures of peer substance use (i.e., target adolescent’s estimations of their peers’ substance use) and studies that used actual peer measures (i.e., nominated peers record their own substance use). A significant moderation effect was found, F(1, 97) = 12.695, p < 0.001 (see Table 2). Both perceived and actual peer measures were found to be significant, with perceived measures having a larger average effect size (k = 54, ββ¯= 0.179, SE = 0.014, 95% CI [0.148, 0.210], p < 0.001) than actual peer measures (k = 45, ββ¯= 0.095, SE = 0.021, 95% CI [0.050, 0.141], p < 0.001).

Mean Age at Baseline

To examine the moderating effect of participants’ age, a linear and a quadratic model were executed. This was due to evidence suggesting that peer influence effects operate in both a linear manner, with an overall increase from childhood to adolescence, and in a curvilinear way, peaking during mid-adolescence (Trucco, 2020). As shown in Table 2, neither model yielded significant results. This suggests that the strength of peer influence effects does not differ with participant age.

Time Lag

The time lag between assessments was examined following the Lag-as-Moderator Meta-Analysis approach (Card, 2019). This model yields both a linear (i.e., peer influence becoming larger or smaller with longer time spans) and quadratic (i.e., peer influence reaching a maximum effect at a particular lag length) moderation of lag, which is centred on the weighted mean. These analyses revealed no significant effect of time lag for neither linear nor quadratic term (see Table 2).

Multivariate Moderation Model

A multivariate moderation model simultaneously examining all five main moderators (i.e., substance use behaviour, peer substance use measure, time lag, age, and gender) revealed no significant differences.

Publication Bias

Publication bias is a potential threat to all systematic reviews, despite efforts to locate unpublished effect sizes. To evaluate and quantify the impact of publication bias, inverse sampling variance moderation analyses were conducted, and a funnel plot was assessed (see Fig. 4). In the absence of publication bias, the plot should present a symmetrical funnel shape centred on the mean effect size. This means that studies with smaller sample sizes or larger standard errors will scatter widely at the bottom of the plot, while those with larger sample sizes or smaller standard errors have a narrower dispersion. Visually inspecting the funnel plot reveals that the effect sizes (indicated as dots on the plot) largely fall in the inverted funnel shape. For a more robust evaluation, the moderating effect of the inverse sampling variation was calculated, which yielded nonsignificant results (β = 0.000013, SE = 0.00001, 95% CI [-0.00002, 0.00004], p = 0.264). Taken together, the funnel plot and inverse sampling variance moderation suggest that publication bias is not significantly contributing to the results.

Discussion

As hypothesised, the results revealed a significant positive effect (ββ¯= 0.147) of peer influence on adolescent substance use, suggesting that adolescents will change their substance use behaviour in the same direction as their peers. It is important to recognise that this finding also implies that target adolescents with peers using substances at low levels are likely to decrease their substance use behaviour over time (Allen et al., 2022). No significant results emerged to suggest that publication bias is prevalent in this study. In line with the hypotheses, significant differences emerged between the substance use behaviours. As expected, target adolescents significantly changed their alcohol, tobacco, and composite substance use over time in accordance with the level of substance use behaviour of their peers. Alcohol use emerged as having the largest average cross-lagged correlation coefficient (ββ¯= 0.182), which was predicted due to it being the most normalised and prevalent substance use behaviour. The smallest effect size was for tobacco (ββ¯= 0.068), which is likely due to small populations of participants engaging in tobacco smoking behaviours. Only a few studies (k = 3) differentiated marijuana use, with majority of studies that used a composite substance use measure including marijuana. Composite substance use emerged as significant with the same effect size as marijuana (ββ¯= 0.134), although marijuana use was not significantly different. Recent Australian survey results found marijuana to be the most commonly used illicit substance among 12–17 year olds, with 8.2% of 14–17 year olds reporting recently using marijuana in 2019, which was an increase from 7.9% in 2016. It is likely that marijuana use not being significant is due to the small number of studies examining it, and that the composite measure is a better representation of peer influence effects on marijuana use.

Consistent with the hypotheses, a significant moderation effect was revealed for perceived vs. actual peer measures, and perceived measures estimated a larger average cross-lagged correlation coefficient (ββ¯= 0.179) than actual peer measures (ββ¯= 0.095). This is consistent with social norm theories, which suggest that adolescents tend to overestimate their peers’ substance use behaviour and that this perception is sufficient to influence target adolescent behaviour (Trucco, 2020). This was reinforced by Helms et al. (2014) who found that adolescents significantly misperceived the substance use of popular peers; however, it contradicts Urberg et al. (2003) who found that adolescents would only conform to peer substance use behaviour if the friendship was positive and reciprocated. This contradiction captures many of the debates about peer influence and lends support to Allen et al.’s (2022) theory that peer influence effects are normative and adaptive; different from the maladaptive effects that can occur from interaction with a problematic subculture or norms. Contrary to the hypothesis, the results showed no linear or quadratic effect of age on peer influence. This finding may be due to the limited variance in age range and variations in the age of puberty, rather than no actual difference. Additionally, no significant effects emerged for time lag or gender. The multivariate moderation model which examined all five moderators simultaneously revealed no significant differences, which was contrary to the univariate analyses for substance use behaviour and peer influence measures. This contradictory result raises questions about the robustness of the moderation analysis results and suggests that peer influence is a complex phenomenon with interacting factors.

Strengths and Limitations

While great effort went into ensuring this study was a comprehensive synthesis and robust meta-analysis, there are significant limitations to consider. Firstly, this study addressed peer influence processes in general, rather than specifically investigating whether the nature of the peer relationship moderates the effect. Considering that the included studies used measures from peers of varying degrees of friendship to the target adolescent, there remains the question of whether the closeness of friendship impacts peer influence processes. Additionally, broader group influence processes may behave differently, with groups of peers exerting an amplifying effect on behaviour. Secondly, the study did not consider differences in the degree to which a peer may actively attempt to be influential. It is suggested that adolescents are more influenced by supportive peers, rather than those who are more coercive and pressuring; however, it may be that coercive peer behaviours have a short-term impact on behaviour in a given situation but aren’t captured by the time lags in the included studies (Allen et al., 2022). Thirdly, while care was taken to collate studies from a variety of nationalities, almost all the records included in the meta-analysis are from cultures that value individualism more highly. A meta-analysis by Liu et al. (2017) found a significant effect of individualism-collectivism, with adolescents from cultures scoring more highly on collectivism being more likely to conform to normative influence from peers. The current review only included one study from a country that scored equal to or above 50 on collectivism, as per Liu et al. (2017) measure, which was Li et al.’s (2017) investigation into tobacco use by Chinese adolescents. This suggests that the results attained in this study may not be representative of peer influence effects in more collectivistic cultures. Additionally, individualism-collectivism is not the only cultural consideration, as peer influence processes may operate differently among adolescents from different countries due to variations in the prevalence of substance use, the availability of substances, laws and policies, social norms, and other cultural factors.

While the results suggested that publication bias was not significantly impacting the results, it is an important consideration in systematic reviews, as many studies that find no significant results or negative results are not published. This ‘file drawer problem’ leads to effect sizes generated in meta-analysis being overestimated. Therefore, it is best practice when conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis to conduct a ‘snowball’ search of reference lists and contact prominent authors on the research topic and request any unpublished studies. Unfortunately, due to the time restraints and scope of this study, previous authors were not contacted, although several unpublished manuscripts were identified and included through reference list searches. It is therefore possible that unpublished data that would contribute to this topic was missed.

Future Research

As social media continues to grow and evolve, future research should look at the processes of online peer influence. Social media has created a new context through which adolescents interact with their peers, as well as perceive peer behaviours and norms (Choukas-Bradley & Nesi, 2020). Additionally, social media is now populated by ‘influencers’ who earn money based on their ability to impact the purchasing decisions of their audience. Influencers present an interesting case, as the influence processes occur exclusively online and often without any direct interaction or reciprocal exchange with users. Research into the impact of social media influencers on adolescents’ decisions to engage in risky behaviours would be worthwhile. Hamilton et al. (2022) noted the potential for online peer influence to be both positive and negative in the context of COVID-19, with images and videos shared by peers practicing safe social distancing practices influencing adolescents to also engage in pro-social health behaviours, while the opposite was also true. Developing a more nuanced understanding of influence processes through social media and identifying the factors that moderate both problematic and productive social media use would be an important area for future research. Additionally, another concerning trend is that of smoking electronic cigarettes. While cigarette smoking is declining overall, with only 5% of Australian secondary school students aged 12–17 reporting being current smokers in 2017, 14% of those students had tried e-cigarettes and vaping e-cigarettes is significantly increasing (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2022). Future research into e-cigarette use in adolescents and whether normative peer influences are greater for vaping than for traditional tobacco smoking would be valuable.

As is common in psychological research, the systematic review yielded few studies in non-Western countries. As mentioned previously, a significant limitation of this study was the overreliance on studies based in Western individualistic cultures, with Li et al.’s (2017) investigation into tobacco use in China being the only non-Western record included. A review by Liu et al. (2017) revealed significant differences in smoking initiation and continuation based on the country’s collectivism-individualism measure, indicating a need for studies with diverse populations. Lastly, future research that conceptualises peer influence as an overall adaptive phenomenon with a neutral valence and investigates the broader subcultures that may be contributing to adolescent substance use would be worthwhile (Allen et al., 2022). With the wealth of research on peer influence and findings that peer influence effects can often overcome targeted interventions, looking past the question of the magnitude of these processes, and instead focusing on the adaptive and maladaptive norms within peer contexts may provide better information about how to prevent adolescents from engaging in substance use behaviours.

Conclusion

The main aim of this study was to systematically review the large body of literature on peer influence from the past 50 years and quantify the magnitude of peer influence on adolescent substance use behaviour using the best available methodologies. The results revealed a significant positive effect (ββ¯= 0.147), indicating that adolescents whose peers engage in greater or lesser substance use behaviour are significantly likely to alter their own substance use accordingly over time. These findings support the existing literature which identified peer influence processes as contributing to adolescents’ decisions to engage in substance use behaviours. Significant heterogeneity was found between the effect sizes across multiple levels, suggesting that unexamined contextual, individual, and methodological factors may modify peer influence effects. Moderation analyses revealed significant differences between different substance use behaviours and between studies that used perceived vs. actual peer measures; however, when assessed simultaneously no moderators emerged as significant. This suggests that peer influence works through complex processes across substance use behaviours, and that attempting to quantify its magnitude may be innately flawed. Overall, findings from this meta-analysis reveal a significant and robust positive effect for peer influence on adolescent substance use. Definitively establishing the impact of peer influence across multiple substance use behaviours and peer measures of substance use has significant implications for adolescent substance use prevention. This includes the potential of harnessing peer influence as a positive force and the need to target misperceptions of substance use, as well as providing an opportunity to focus on the adolescent subculture and norms that are contributing to risky health behaviour. Research has demonstrated that interventions targeting peer influence are largely ineffective in preventing substance use behaviour in adolescents, potentially due to peer influence representing an overall adaptive developmental phenomenon. Therefore, the emphasis of future studies in preventing dangerous substance use behaviour should look less at peer influence and more at the adolescent subcultures that support problematic behaviour.