[PROPOSED] BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE DEVELOPMENTAL SCIENCE SCHOLARS AND NONPROFITS

STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED

Should People v Parks, 510 Mich 225 (2022)—which held that the Michigan Constitution prohibits mandatory life-without-parole (“LWOP”) sentences for late adolescents aged 18 due to their incomplete brain and behavioral development— apply equally to late adolescents aged 19 and 20 undergoing identical development?

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

People v Parks held that Article 1, Section 16 of the Michigan Constitution prohibits the Government from condemning late adolescents aged 18 at the time of their offenses to mandatory LWOP because the “fail[ure] to take into account the mitigating characteristics of youth, specifically late-adolescent brain development” renders those sentences disproportionate and unlawful. Parks, 510 Mich at 232.

Parks centered on the modern scientific consensus, detailed in amici’s brief filed in Parks as well as this Brief, that “[t]he brains of 18-year-olds, just like those of their juvenile counterparts, transform as they age, allowing them to reform into persons who are more likely to be capable of making more thoughtful and rational decisions,” such that those “same features that characterize the late-adolescent brain also diminish the culpability of these youthful offenders, rendering them less culpable.” Id. at 258–59. As amici’s earlier brief explained and as Parks expressly found, brain and behavioral maturation throughout late adolescence means that late adolescents, “like their juvenile counterparts, are generally capable of significant change and a turn toward rational behavior that conforms to societal expectations as their cognitive abilities develop further.” Id. at 258. These findings led this Court to conclude that, given “the dynamic neurological changes that late adolescents undergo as their brains develop over time and essentially rewire themselves, automatic condemnation to die in prison at 18 is beyond severity—it is cruelty.” Id.

Parks addressed an as-applied challenge, and so this Court only had occasion to extend the Michigan Constitution’s protections for late adolescents aged 18 like defendant Kemo Parks at the time of his offense. Yet, there is no question that every ounce of the Court’s findings and reasoning in Parks involving late adolescents aged 18—i.e., the scientific consensus on their ongoing brain and behavioral development during late adolescence; its impact on their propensity for risky, impulsive, and peer induced behavior; its implications for their remarkable rehabilitative potential; and the constitutional protections guaranteed to them by Article 1, Section 16—“applies in equal force” to all late adolescents aged 18-20. Id. at 241, 249–52, 257–59, 264–66. Indeed, the leading studies in developmental science, many authored by amici themselves and cited favorably throughout Parks, focused on and made findings for late adolescents aged 18-20 as a group, without distinguishing 18-year-olds.

Given all this, the Government’s position here, that this Court should forsake Michigan’s constitutional safeguards against mandatory LWOP for late adolescents, is simply irreconcilable with developmental science and with Parks itself. The Government’s arguments also stand in stark tension with its implicit concession in Parks “that, in terms of neurological development, there is no meaningful distinction” between adolescents under 18 and late adolescents. Id. at 252. So just as mandatory LWOP constitutes a disproportionate sentence for 18-year-olds because it fails to account for their mitigating attributes of late adolescence, such a harsh sentence equally offends Article 1, Section 16 when imposed on late adolescents aged 19-20 who share those same mitigating characteristics.

Accordingly, amici respectfully submit that this Court should invalidate Appellants’ mandatory LWOP sentences and reverse the judgments below.

ARGUMENT

I. Transformative Neurological and Behavioral Changes During Ages 18-20 Establish Mandatory LWOP as a Disproportionate Sentence for Late Adolescents in Violation of Article 1, Section 16.

A. Scientific Research Shows Profound Maturation in Brain, Behavior, and Personality Throughout Late Adolescence.

In evaluating whether sentencing late adolescents aged 19-20 to mandatory LWOP violates Article 1, Section 16, this Court “must consider the scientific and social-science research regarding the characteristics of the late-adolescent . . . brain.” Parks, 510 Mich at 248. Amici are part of a scientific community that universally recognizes late adolescence—i.e., the period of transformative growth encompassing ages 18, 19, and 20—as “a key stage of development characterized by significant brain, behavioral, and psychological change.”2 Parks, 510 Mich at 249. “This scientific consensus arises out of a multitude of reliable studies on adolescent brain and behavioral development in the years following Roper, Graham, Miller, and Montgomery.” Id. at 249. Many of these studies assess brain structure and function in large numbers of individuals of different ages and over multiple time points, enabling researchers to use averages to measure accurately the age at which changes in specific brain structures and functions show relative leveling-off or stability.

These “multitude of reliable studies” conclusively establish late adolescence as a “pivotal developmental stage that shares key hallmarks of adolescence.” Id. Late adolescence is marked by ongoing brain maturation in areas that govern emotional arousal and self-control regulation.3 The scientific evidence regarding neurocognitive and behavioral maturation throughout late adolescence powerfully demonstrates that adolescence undoubtedly extends through at least age 20. Accord Parks, 510 Mich at 252 (“[I]n terms of neurological development, there is no meaningful distinction between those who are 17 years old and those who are [late adolescents].”).

Moreover, brain development during late adolescence does not merely entail minor changes in brain structure or function, but rather “a series of developmental cascades” of neurological transformations across multiple brain networks that, in turn, enable late adolescents to transition to the more rational control of behavioral impulses seen in neurological adulthood.4 Given this, from a scientific perspective, a late adolescent’s 19th or 20th birthday is simply not a rational dividing line, as the same mitigating attributes of diminished culpability and capacity for rehabilitation persist throughout late adolescence.5

1. The late adolescent brain has exceptional neuroplasticity between ages 18-20.

“The key characteristic of the adolescent brain is exceptional neuroplasticity.” Parks, 510 Mich at 250. While the human brain has capacity for change (known as “plasticity” or “neuroplasticity”) throughout a person’s life, the brain shows truly remarkable potential for positive transformation throughout late adolescence.6 Influenced by genetics, cognitive development, and upbringing (including trauma and chronic stress), plasticity can radically reshape neural pathways.

During adolescence, the brain undergoes substantial synaptic pruning, in which unused excitatory synapses (connections between neurons) are eliminated to increase efficiency in communication among the remaining neuronal connections, which supports learning, cognition, and reasoned decision-making.7 A “hallmark of the brain transformations of adolescence,” synaptic pruning during adolescence— which continues through late adolescence—removes approximately half the synaptic connections in certain brain regions.8 This marked reduction in synapses corresponds with “the ‘rewiring’ of brain connections into adult-typical patterns.”9 Parks, 510 Mich at 250 (the brain “essentially rewires itself” during adolescence). Late adolescents “are at the peak of their risk for criminality because of the neuroplasticity of their brains, causing a general deficiency in the ability to comprehend the full scope of their decisions as compared with older adults.” Id. at 259.

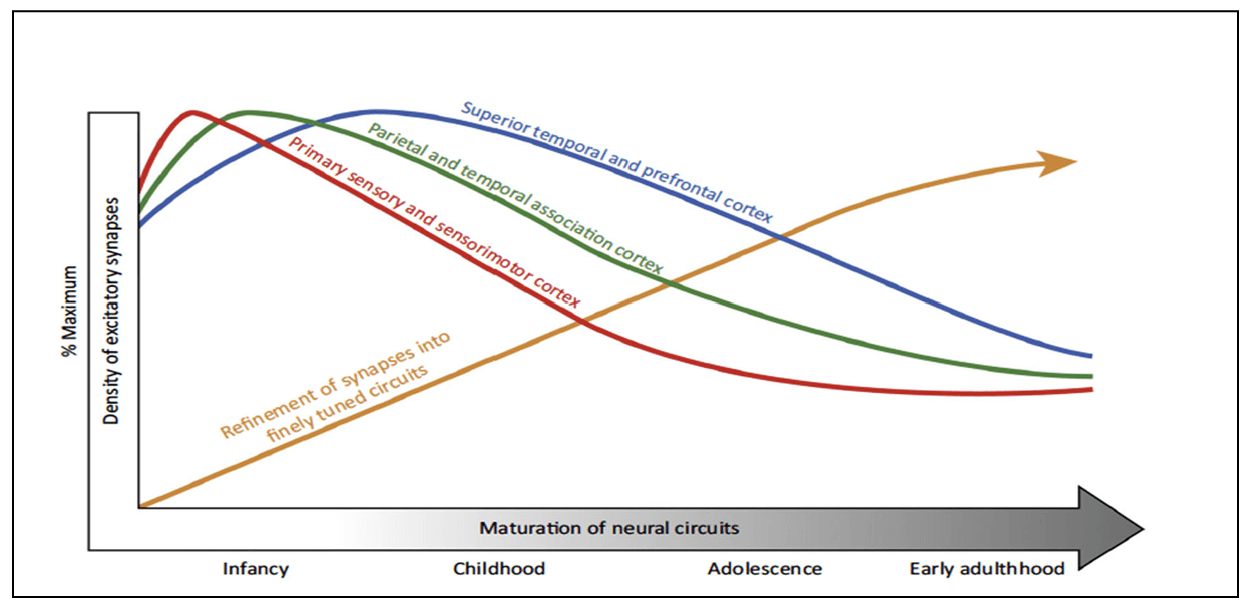

Adolescent brains simultaneously undergo gradual myelination, in which axons (the parts of nerve cells along which nerve impulses are conducted to other cells) become insulated with fatty, insulative tissue known as myelin. Myelination increases the transmission speed of electrical signals. Myelination thus enables the remaining connected neurons to communicate with greater speed and efficiency, even between distant regions of the brain.10 Through at least late adolescence, these developing pathways facilitate greater dialogue among different brain systems that process cognitive, emotional, and social information important for self-control. As shown in Figure 1, these processes together prime the brain for learning and change during late adolescence, especially in pathways involving the prefrontal cortex that supports decision-making and self-control.

Figure 1 - The density and maturation of various neural circuitry over time. Jennifer K. Forsyth & David A. Lewis, Mapping the Consequences of Impaired Synaptic Plasticity in Schizophrenia Through Development: An Integrative Model for Diverse Clinical Features, 21 Trends Cogn Sci 760–78, 765 (Oct. 2017).

2. Brain imaging provides definitive evidence of crucial neurological development for late adolescents aged 18-20.

The brain shows dynamic changes in structure and function throughout late adolescence. Imaging tools like functional magnetic resonance imaging (“fMRI”) provide researchers with the ability to see structural changes in tissue (gray and white matter) related to processes at the level of the synapse and myelin sheath and functional changes related to neuronal activity.

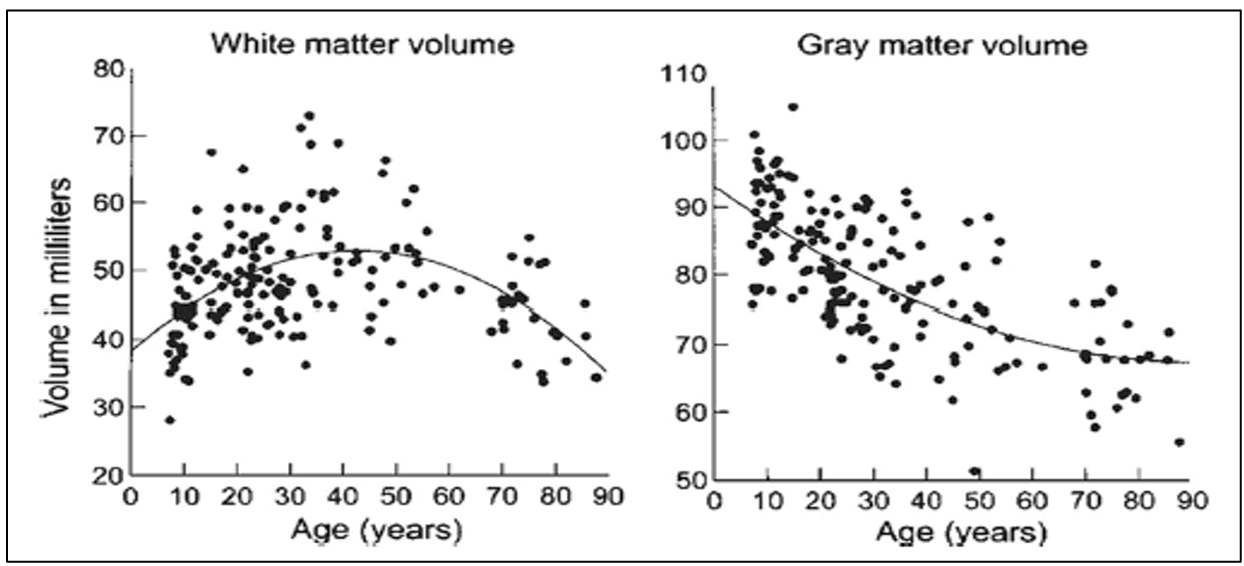

This increased visibility into late adolescent brain development shows significant changes in gray and white matter that extend through ages 18-20. Figure 2 below demonstrates findings across white and gray matter volume, which are key brain metrics related to changes in cognitive abilities (including decision making, self-control, and social and emotional behavior):

Figure 2 - Changes in white and gray matter volume through life. Elizabeth R. Sowell et al., Mapping Cortical Change Across the Human Life Span, 6 Nature Neuroscience 309–15, 314 (Jan. 2003)

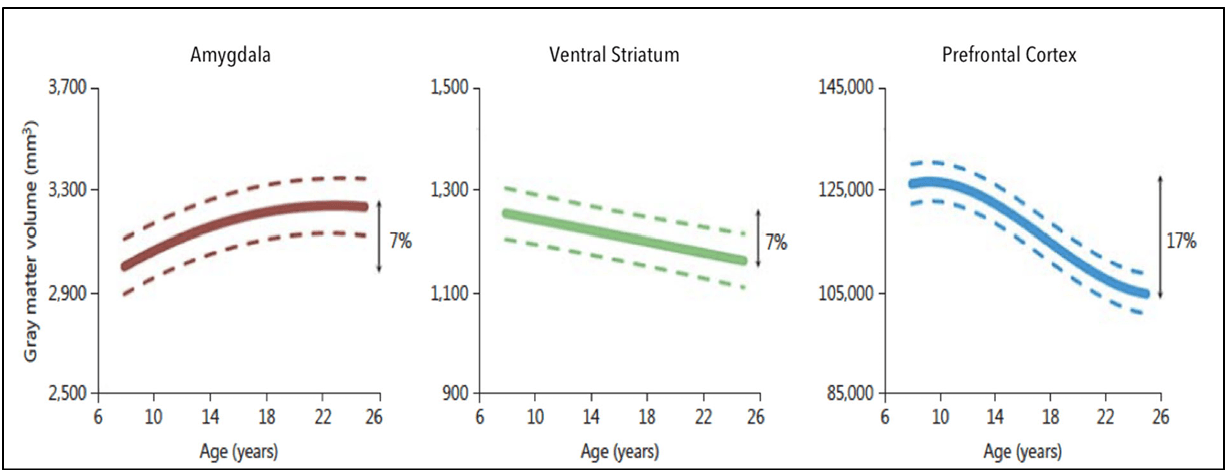

Gray matter development: The thinning and refinement of cortical gray matter (the regions containing most of the brain’s neuronal cells) is correlated with improved decision-making and self-control. That refinement continues through an individual’s late twenties and beyond—and is associated with continued synaptic pruning during late adolescence.11 Gray matter changes also demonstrate disparate regional development as shown in Figure 3 below. The prefrontal cortex that modulates cognitive control shows a dramatic 17 percent reduction in gray matter volume between ages 6 to 26. By comparison, over the same period, the subcortical regions implicated in emotional and motivation processing, the amygdala and ventral striatum, exhibit a 7 percent reduction.12 These results track a developmental mismatch during late adolescence between (i) the less developed brain regions controlling foresight, planning, self-control, and risk-aversion, and (ii) the more developed and dominant brain regions implicated in states of emotional arousal.

Figure 3 — Gray matter volume in the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex from childhood to early adulthood. Mills, supra note 12 at 153.

White matter development: White matter increases throughout late adolescence, including ages 18-20, and is thought to reflect heightened brain processing, impulse control, and reasoned decision-making.13 Associated with gradual myelination and the brain’s stimuli processing speed, the incomplete development of these connections throughout childhood and late adolescence has been implicated in diminished self-control and increased impulsive and risky behavior.14 During late adolescence, white matter connections between the prefrontal cortex and subcortical regions multiply and mature, contributing to improved self-control needed for neurocognitive adulthood.15

Functional brain development: Functional brain development is assessed during rest or during a task. Resting-state functional MRI (“fMRI”) measures correlations in spontaneous activity between brain regions over time when resting and is referred to as functional connectivity. Task-based fMRI looks at regional changes in brain activity in response to stimuli or performance of a task. Functional connectivity, believed to inform reasoned decision-making and self-control, shows continued improvement through at least age 20.16

During adolescence, including late adolescence, a transition occurs from a state that features more local connections to one that exhibits strengthened distal connections. Both functional connectivity and task-based prefrontal activity appear less mature under conditions of emotional arousal (e.g., threat anticipation) relative to non-arousing ones. Under emotionally arousing conditions, adolescents under 18 and late adolescents aged 18-20 exhibit more impulsivity and riskier preferences compared to neurological adults, suggesting greater susceptibility to situational diminished capacity in late adolescence.17 Accord Parks, 510 Mich at 250 (“late adolescence is characterized by impulsivity, recklessness, and risk-taking”).

These studies collectively show that late adolescence is a time of substantial ongoing maturation and development in the regions and circuits of the brain that process information associated with rewards and emotional reactivity. This is especially true for regions of the brain, like the prefrontal cortex, that are important for decision-making and impulse control.18 Thus, Parks correctly found that “late adolescents are hampered in their ability to make decisions, exercise self-control, appreciate risks or consequences, feel fear, and plan ahead.” Parks, 510 Mich at 250.

As the brain matures, particularly from late adolescence into early adulthood, changes in subcortical and cortical pathways are associated with improved cognitive capacity in social and emotional situations and a substantial reduction in a late adolescent’s propensity to engage in reckless behaviors.19 “[T]hese hallmarks of the developing brain render late adolescents less fixed in their characteristics and more susceptible to change as they age.” Parks, 510 Mich at 251. So while the transformations during late adolescence make them particularly vulnerable to certain forms of transient mistakes and misconduct, those processes do not freeze them in this state permanently. To the contrary, their brains develop into neurological adulthood, at which point they are more mature, more in control, and less likely to engage in wrongdoing.20 Parks, 510 Mich at 258 (“The brains of [late adolescents], just like those of their juvenile counterparts, transform as they age, allowing them to reform into persons who are more likely to be capable of making more thoughtful and rational decisions.”).

3. The brain undergoes lopsided development rendering late adolescents aged 18-20 uniquely vulnerable to risk-taking and peer-induced behavior.

Brain development is a dynamic and hierarchical process that occurs throughout life, and especially during late adolescence. Recent scientific findings demonstrate that, due to the uneven timing of certain brain development processes, late adolescents are particularly susceptible to maladaptive behavior, and their proclivity for such behavior recedes upon reaching adulthood.

Brain systems and the connections between them undergo substantial refinement with age. The timing of these changes, however, varies for different brain regions and networks. Subcortical regions including the ventral striatum and amygdala, which are important for reward perception and emotional input, show earlier structural and functional development than cortical regions.21 By contrast, the prefrontal cortex, which guides self-control and reasoned decision-making, continues to mature throughout late adolescence into neurological adulthood.

At the tail-end of late adolescence, the brain’s development exhibits a crucial shift. Where the younger brain predominantly relies on emotional, or limbic, circuitry, this period facilitates the transition to a neurocognitively adult brain that relies more on the cognitive control, or prefrontal, circuitry.22 While both brain systems play important roles in decision-making, limbic circuitry dominant in adolescence governs short-term reward/pleasure (through the ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex)23 and emotional arousal (through the amygdala, hippocampus, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex).24 By contrast, the prefrontal circuitry (lateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex) dominant in adulthood regulates cognitive control responses such as reasoning, attention, planning, and memory retrieval. When fully developed, this brain system facilitates a person’s ability to efficiently engage in complex decision-making by weighing alternative choices and actions based on future objectives and consequences.

This extended window of prefrontal maturation parallels the prolonged social, emotional, and cognitive development that marks late adolescence.25 Because the prefrontal cortex is more developed during late adolescence than in earlier stages of adolescence, late adolescents have somewhat better cognitive control and decision making skills than they did when they were younger. However, because the brain’s motivational and emotional systems are hyper-responsive through late adolescence, late adolescents tend to be more vulnerable than neurological adults to lapses in self control or impulsive decision-making—especially when in emotionally heated situations.26 In other words, late adolescents are predisposed to behave immaturely or impulsively under emotionally heightened circumstances.27

Late adolescents aged 18-20 are uniquely vulnerable to impulsive and risky behavior because their more developed emotional circuitry induces outsized response to short-term rewards and overreaction to perceived threats. Accord Parks, 510 Mich at 251 (Late adolescents “have yet to reach full social and emotional maturity, given that the prefrontal cortex—the last region of the brain to develop, and the region responsible for risk-weighing and understanding consequences—is not fully developed until age 25.”). For late adolescents, dramatic changes are believed to occur in the prevalence and distribution of dopamine receptors across the brain.28 These neurological changes favor fleeting rewards and pleasure and correlate with a spike in risk-taking and peer-influenced behaviors.

When faced with acute stress or emotional arousal, late adolescents’ supercharged threat and stress response and eagerness for short-term rewards are more likely to culminate in poor decision-making, weak impulse control, and limited regard for future consequences. Parks, 510 Mich at 251 (late adolescents “are more sensitive to the potential rewards as opposed to the potential consequences or costs of a decision” and are “more susceptible to negative outside influences, including peer pressure”). This is equally true for late adolescents aged 18-20. The conflicting interactions within and between their more developed limbic system and their less developed prefrontal system contributes to a heightened propensity to engage in irresponsible conduct.29 The cognitive control system begins to develop in infancy through at least late adolescence via a slow process that requires multiple systemic changes, and only by neurological adulthood better moderates such impulses.30

As brain imaging studies suggest, the ability to engage in mature decision making through effective impulse control, risk avoidance, and coordination of emotion and cognition is not fully developed until after late adolescence is complete.31 After that point, the brain systems are more evenly developed, such that the systems and the neural pathways linking them can interact to enable suitable regulation of perceived incentives, threats, and consequences. Parks, 510 Mich at 258 (Late adolescents, “as they age, are likely to begin to take fewer risks, further understand consequences, become less susceptible to peer pressure, and have decreased aggressive tendencies.”). This understanding from contemporary neuroscience offers a powerful explanation not only as to why late adolescents aged 18-20 are uniquely vulnerable to engaging in risky and irresponsible behaviors, but also as to why their proclivity for doing so naturally recedes upon reaching neurocognitive adulthood.32

4. Late adolescent brains, especially under stress, resemble under-18 adolescent brains.

Neuroscientists have discerned age brackets for which brain imaging data indicates greater neurological similarities than differences, notwithstanding marginal differences in physical or neurocognitive ages. It is exceedingly difficult to differentiate the brain images of adolescents aged 17 and late adolescents aged 18 20.33 Parks, 510 Mich at 252 (“[L]ate-adolescent brains are far more similar to [under 18 adolescent] brains . . . than to the brains of fully matured adults.”). This is due to strong similarities in brain immaturity as well as changes in functional connectivity between brain systems that persist throughout this developmental period.34 Late adolescent brain images also reveal indistinguishable levels of underdeveloped functional connections, and that incomplete maturation manifests most acutely under emotional arousal and stressful states where serious offenses tend to occur.35

These findings suggest that, in emotionally charged and peer-influenced situations, the late-adolescent brain manifests as less mature than in calm, controlled environments, and that this immaturity is linked to risky behaviors.36 “This results in a late adolescent often behaving more similarly to a 14- or 15-year-old, as opposed to an older adult, when in the presence of their peers.” Parks, 510 Mich at 251. The neuroscientific evidence demonstrates that brain function and cognitive capacity vary as a function of emotional and social contexts and that full adult capacity in these contexts is not generally observed until after late adolescence—even though late adolescents may appear, from external appearances, to be fully mature.

5. Psychological capacity matures throughout late adolescence.

The brain’s transformative development during late adolescence is intertwined with changes in psychological and cognitive abilities, as well as social and emotional responses, which, in turn, impact sentencing considerations such as culpability and capacity for change. See Parks, 510 Mich at 250–51; Graham v Florida, 560 US 48, 68 (2010).

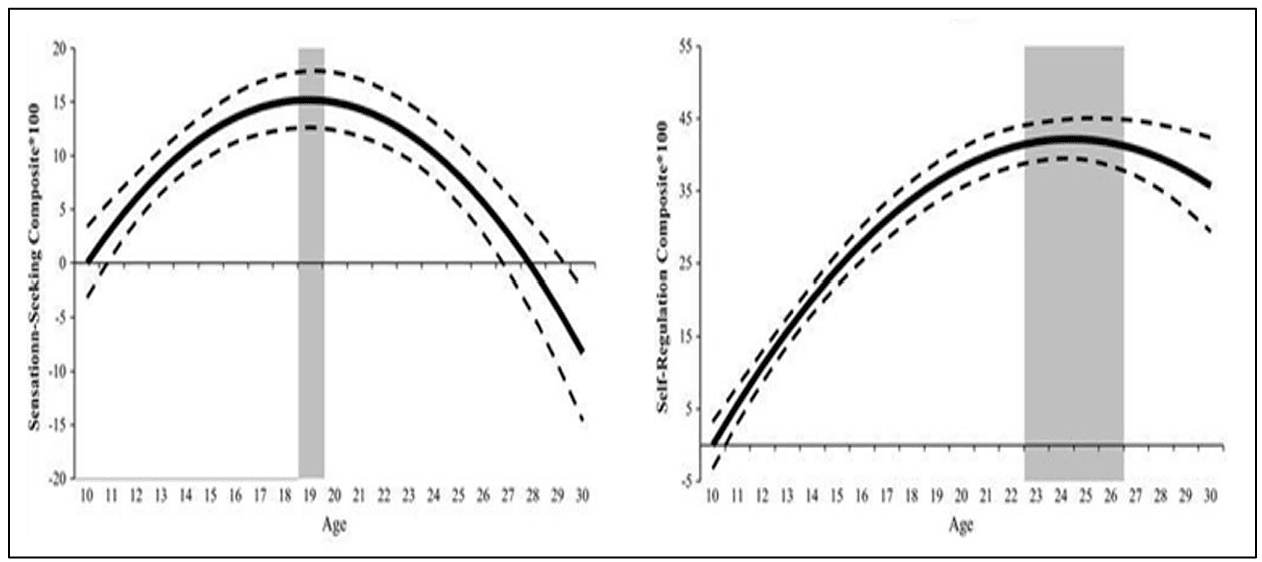

The scientific literature makes clear that different psychological abilities develop at different times, in keeping with gradual biological changes in the brain. Strategic behaviors involving planning and decision-making under demanding and emotionally arousing conditions show steady improvements beyond 18 years.37

Adolescents, including late adolescents aged 18-20, still show diminished capacity in such scenarios, exhibiting heightened sensitivity to rewards, threats,38 social cues,39 and peer influences40—combined with an underappreciation of risks, consequences, and self-regulation.41 Figure 4 below provides a visual representation of these changes in sensation-seeking and self-regulation.42 This heightened sensitivity can distract individuals and bias decisions in suboptimal ways for late adolescents, such as placing them at a greater risk for criminal activity.43 Under situations of threat, their cognitive capacity is diminished and does not exhibit mature levels by age 20.44 Indeed, distinguishing the capacity of a 17-year-old from a late adolescent aged 18 - 20 in these situations would be functionally impossible.

Figure 4 - Sensation-seeking peaks in late adolescence (left). Self-regulation stabilizes in young adulthood right). Steinberg et al., supra note 42.

This Court rightly recognized that “this period of development also explains why a [late adolescent] is more susceptible to negative outside influences, including peer pressure.” Parks, 510 Mich at 251. See also Graham, 560 US at 68 (vulnerability “to negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure” is a mitigating attribute of adolescence). Several studies have found heightened risk-taking by late adolescents in the presence of peers compared to being alone or with neurological adults, whereas peer pressure has little impact on risk-taking among neurological adults.45 “This susceptibility to peer pressure exacerbates late adolescents’ predisposition to risk-taking and deficiencies in decision-making.” Parks, 510 Mich at 251.46

This wealth of literature addressing the development of psychological abilities confirms there is little difference between adolescents under 18 and late adolescents aged 18-20 regarding cognitive capacity in demanding and emotionally charged situations. Three key findings emerge. First, as a group, late adolescents show immature psychological abilities relative to neurological adults. Second, cognitive, emotional, and social abilities do not develop on the same timeline. Third, these abilities fully coalesce only after late adolescence.47 As such, late adolescents aged 18-20 may make rational decisions in some contexts, such as choosing to attend college or voting, but still struggle with mature decision-making in charged scenarios where peer influences, threats, or short-term incentives are acutely felt.

6. Trauma and chronic stress impact brain and behavioral development through late adolescence.

Adversity in adolescent experiences and related traumas can alter standard brain development and cognitive and perceptual processes.48 Such events increase the risk of neurocognitive immaturity during late adolescence,49 stunted emotional development, and limited self-control and other regulatory processes—all of which exacerbate poor decision-making and maladaptive behaviors (including criminal conduct).50 Late adolescents aged 18-20 who have experienced significant adversity may present a much lower neurocognitive age, given the resounding impacts of prior trauma on their cognitive maturity.51 This important evidence highlights the lack of a scientific basis for treating late adolescents aged 18-20 differently from adolescents under 18, especially if they have experienced trauma.

Thankfully, the brain shows remarkable plasticity in its potential to adapt to changing environments, even extreme ones (including chronic stress, neglect, and abuse)52 throughout the lifespan.53 Consequently, even with significant prior trauma, studies have shown that sufficient time in healthier environments and exposure to effective rehabilitative interventions can mitigate the past effects of adverse environments54 and curb impulsive behaviors into neurological adulthood.55 The brain’s long-term capacity to remedy the effects of past adversity when met with appropriate rehabilitative frameworks is remarkable and reveals potential for redemption for all late adolescents aged 18-20.56

7. Personality matures throughout late adolescence.

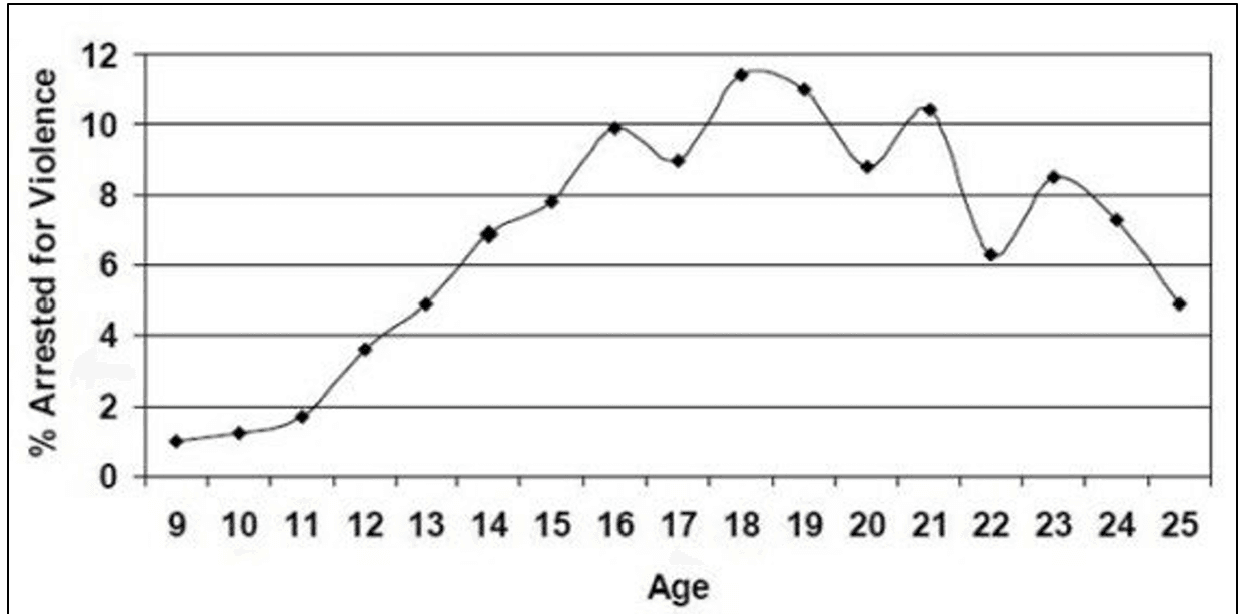

Numerous studies have dispelled the once-fashionable idea that personality emerges early and remains stable from age 18 onward. Research now demonstrates that people generally show increased self-control and emotional stability as they age, with dramatic increases throughout late adolescence.57 See Sections I.A & I.B, supra. The classic “age-crime” curve illustrated in Figure 5 reflects, among other things, individuals’ growing self-control and emotional stability over time. Statistics consistently show that criminal conduct—especially the incidence of violent offenses—peaks during late adolescence and declines significantly after age 21.58

Figure 5 — Distribution of persons arrested for violence by age. See National Institute of Justice, From Youth Justice Involvement to Young Adult Offending (Mar. 2014)

Psychological studies track a similar pattern and show that extreme forms of antisocial behavior and pathological personality traits naturally diminish after late adolescence.59 After late adolescence, antisocial behavior and callous-unemotional and psychopathic traits decrease for the majority of neurological adults.60 When individuals age out of late adolescence, their brain and psychological development naturally reduces their propensity to engage in criminal acts. As a result, mandatory LWOP sentences for late adolescents are not justified based on the flawed premise of a “pathological” personality or purported need to deter future crimes or protect members of the public.

B. Parks and Lorentzen Compel the Conclusion that Const 1963, Art 1, § 16 Shields Late Adolescents Aged 18-20 from Mandatory LWOP Sentences.

Given the scientific consensus in Section I.A supra, the reasoning in Parks leaves no question that Const 1963, art 1, § 16’s protections against mandatory LWOP for late adolescents aged 18 apply equally to late adolescents aged 19 and 20. “[T]he same features that characterize the late-adolescent brain also diminish the culpability of these youthful offenders, rendering them less culpable than older adults.” Parks, 510 Mich at 258–259. That is because late adolescents aged 18–20 “are at the peak of their risk for criminality because of the neuroplasticity of their brains, causing a general deficiency in the ability to comprehend the full scope of their decisions as compared with older adults.” Id. at 259. Late adolescents “transform as they age, allowing them to reform into persons who are more likely to be capable of making more thoughtful and rational decisions.” Id. at 258.

Despite compelling scientific evidence of ongoing brain and behavioral development and rehabilitative potential for all late adolescents aged 18-20, Michigan’s “sentencing structure mandatorily condemns all [late adolescents aged 19-20] who are convicted of certain crimes to [LWOP] without considering whether they are capable of positive change and without any consideration of their lessened culpability, both of which are undeniable neurobiological facts.” Id. at 259. Simply put, the “current sentencing scheme fails to consider whether [late adolescents aged 19-20] are irreparably corrupt, whether they have the capacity to positively reform as they age, and whether they committed their crime at a time in their life when they lacked the capability to fully understand the consequences of their actions.” Id. This callous sentencing regime, in which all 19-20 year olds are reflexively presumed incorrigible, as it stands, squarely contradicts the Michigan Constitution’s “important belief that only the rarest individual is wholly bereft of the capacity for redemption.” People v Bullock, 440 Mich 15, 39 n 23 (1992) (cleaned up).

So, just as this Court made clear in Parks for late adolescents aged 18, amici respectfully submit that, “[b]ecause of the dynamic neurological changes that late adolescents undergo as their brains develop over time and essentially rewire themselves, automatic condemnation to die in prison at [19-20] is beyond severity— it is cruelty.” Parks, 510 Mich at 258. “Such an automatically harsh punishment without consideration of mitigating factors is unconstitutionally excessive and cruel.” Id. at 259–60; cf. Graham, 560 US at 70 (LWOP “is an especially harsh punishment” given the mitigating attributes of adolescence). Under the current regime mandating LWOP for late adolescents aged 19 and 20, late adolescents must “spend more time behind prison bars than any other adult defendants convicted of the same crime or similarly severe crimes” which is “disproportionate.” Parks, 510 Mich at 260.

To assess whether a given sentence constitutes cruel or unusual punishment, Michigan courts apply the four-factor test in People v Lorentzen, 387 Mich 167, 176 81 (1972), scrutinizing: “(1) the severity of the sentence relative to the gravity of the offense; (2) sentences imposed in the same jurisdiction for other offenses; (3) sentences imposed in other jurisdictions for the same offense; and (4) the goal of rehabilitation.” Parks, 510 Mich at 242, 254–55; see also Bullock, 440 Mich at 33–34. As analyzed below, each of these factors applied here “compels the conclusion that mandatorily subjecting [late adolescents aged 19-20] to life in prison, without first considering the attributes of youth, is unusually excessive imprisonment and thus a disproportionate sentence that constitutes ‘cruel or unusual punishment’ under Const 1963, art 1, § 16.” Parks, 510 Mich at 255.

First, relative to the offense, mandatorily sentencing late adolescents aged 18-20 to LWOP reflects unduly severe punishment. Parks, 510 Mich at 256–57. Even for serious offenses, the permanent and unforgiving nature of mandatory LWOP is “particularly acute” for late adolescents aged 18-20 because it (1) condemns them to “a greater percentage of their lives behind prison walls than [neurological] adult offenders,” id. at 257, and (2) wholly disregards their mitigating attributes of late adolescence, despite the scientific consensus on late adolescent brain and behavioral development. See Section I supra. Starting with the severity of the sentence, “other than the death penalty, [mandatory LWOP] is the most severe sentence still available in the whole country” and means that “late-adolescent defendants [aged 18-20] are faced with a prison sentence to be served for the remainder of their biological lives, with no possible hope of release.” Id. at 258 n 11; see also id. at 260 (reasoning that mandatory LWOP is only justifiable for “those whose criminal culpability mandates automatic, permanent removal from society”).

Turning to the mitigating attributes of late adolescence, this Court clarified in Bullock that all sentences “must be tailored to a defendant’s personal responsibility and moral guilt.” 440 Mich at 39 (quotation marks and citation omitted). And yet, for late adolescents aged 19-20, the “automatically harsh punishment” of mandatory LWOP precludes courts from taking into account “undeniable neurobiological facts” regarding their incomplete brain and behavioral development. Parks, 510 Mich at 259–60; see Section I.A supra. Those neurobiological facts reduce their “personal responsibility and moral guilt” in light of their situational diminished capacity, especially in stressful and peer-influenced situations, and demonstrate their exceptional “capacity to positively reform as they age.” Parks, at 259, quoting Bullock, 440 Mich at 39. As Parks explained, mandatory LWOP’s failure to consider these mitigating attributes of late adolescence renders these sentences “unconstitutionally excessive and cruel.” Id. at 259–60.

Second, the sentences imposed for other offenses in Michigan further reveal that mandatory LWOP constitutes disproportionate punishment for late adolescents aged 18-20. Under Const 1963, art 1, § 16, “the length of time an offender will spend in prison is undoubtedly a relevant consideration in determining the constitutionality of mandatory [LWOP].” Id. at 257. For individuals who were late adolescents at the time of their offenses, “it is highly probable that [they] will spend more time behind prison bars than any other adult defendants convicted of the same crime or similarly severe crimes. This is disproportionate to other offenders in this state.” Id. at 260 (internal citation omitted). Since their offenses tend to be “reflective of . . . diminished capacity as a late adolescent” as compared to the same offense committed by a neurological adult, “the disproportionality is apparent.” Id. at 261. Therefore, “[i]t is cruel that our current sentencing scheme requires [late adolescents aged 19-20] to, on average, serve far more severe penalties than equally or more culpable” neurological adults. Id.

The gross disparity between Michigan’s bar on mandatory LWOP for late adolescents aged 18, while condoning the punishment for late adolescents aged 19 20, further underscores the untenable nature of those sentences. It is simply “cruel” that those aged 19-20 receiving mandatory LWOP will “spend more time in prison than most of [their] equally culpable” peers, including adolescents under 18 and late adolescents aged 18, even though the Government does not appear to dispute, and this Court has found, that adolescents and late adolescents generally share “equal moral culpability neurologically” based on the mitigating attributes arising out of their incomplete development. Id. at 261–62.

Third, the fact that some states have moved further away from LWOP (whether mandatory or permissive) for late adolescents tips the scales even further against mandatory LWOP’s proportionality here. As an initial matter, as Parks observed, “Washington, with a similarly broad punishment provision in its constitution, judicially found the neurological differences between juveniles and 18 year-olds to be nonexistent and mandated that young adults through the age of 20 also receive the same individualized sentencing protections as juveniles.” Id. at 262 63, citing In re Monschke, 482 P3d 276 (Wash 2021). And perhaps most significantly, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court earlier this year concluded that its state constitution prohibits both mandatory and permissive LWOP for late adolescents aged 18-20, and it did so by contextualizing the same powerful brain and behavioral science that amici proffered in that case, and here. Mattis, 224 NE3d at 421, 423. So, while the Court in Parks already characterized the third Lorentzen factor as “slightly weigh[ing] in favor of an individualized sentencing” for late adolescents aged 18 at the time of Parks, the recent judicial development in Massachusetts since Parks, at minimum, moves the needle “slightly” more in favor of protecting late adolescents against mandatory LWOP. Parks, 510 Mich at 262.

Fourth, the fundamental goal of rehabilitation makes abundantly clear that mandatory LWOP for late adolescents aged 18-20 contravenes Const 1963, art 1, § 16. Rehabilitation is a “criterion rooted in Michigan’s legal traditions” and, [w]ithout hope of release, [late adolescents aged 19-20], who are otherwise at a stage of their cognitive development where rehabilitative potential is quite probable, are denied the opportunity to reform while imprisoned.” Parks, 510 Mich at 265, quoting Bullock, 440 Mich at 34 (internal quotations omitted). Here, “it cannot be disputed that the goal of rehabilitation is not accomplished by mandatorily sentencing [late adolescents] to life behind prison walls without any hope of release.” Id. at 264–65. This is because the scientific consensus unequivocally establishes that these late adolescents remain uniquely amenable to transformative rehabilitation pursuant to cascading changes to their brain and behavior—including neuroplasticity, prefrontal development, psychological growth, and personality maturation throughout late adolescence. See Section I supra; accord Parks at 264–65. In other words, the current sentencing system that deprives late adolescents aged 19-20 of the opportunity for rehabilitation many years down the line, extinguishing any hope for future parole consideration, stands as “antithetical” to the Michigan Constitution’s “professed goal of rehabilitative sentences.” Id. at 265.

Accordingly, just like this Court found in Parks, applying the four Lorentzen factors here compels the finding that Michigan’s current sentencing scheme—which categorically condemns all late adolescents aged 19-20 to LWOP without necessary and appropriate acknowledgment of their mitigating attributes and rehabilitative potential—fails to satisfy the constitutional rigors of Const 1963, art 1, § 16.

II. HALL HAS NO BEARING ON CONST 1963, ART 1, § 16’S PROTECTIONS FOR LATE ADOLESCENTS AGED 19–20.

A holding by this Court that Const 1963, art 1, § 16 prohibits imposition of mandatory LWOP on late adolescents aged 19–20 would not require reconsideration of People v Hall, 396 Mich 650 (1976) for at least three reasons. First, Hall “was decided before the United States Supreme Court decided Miller and its progeny,” which introduced the mitigating attributes of adolescence and underscored the constitutional significance of neuroscience and psychology in informing whether mandatory LWOP constitutes disproportionate punishment. Parks, 510 Mich at 355 n 9, citing Hall, 396 Mich at 657–58. Second, when Hall was decided nearly 50 years ago, this “Court did not have the benefit of the scientific literature” authored and proffered by amici, and which this Court cited in Parks. Id.; see Section I.A supra. Third, Hall’s thread-bare scrutiny of mandatory LWOP, with zero regard for the mitigating attributes of adolescence or late adolescence, firmly establishes Hall as inapposite to the constitutional question presented here.

Consequently, Hall “does not preclude” protections against mandatory LWOP for late adolescents aged 18, nor does Hall “foreclose future review of [LWOP] sentences for other classes of defendants,” including late adolescents aged 19–20. Parks, 510 Mich at 255 n 9. However, to the extent that the Court believes it must reconsider Hall to issue the protective holding compelled by Const 1963, art 1, § 16, reconsideration is necessary and amply justified here given the neuroscientific evidence in this Brief concerning the mitigating attributes of late adolescence and the disproportionate nature of mandatory LWOP for late adolescents.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amici respectfully submit that the Court should find, consistent with Parks, that imposing mandatory LWOP sentences on late adolescents aged 19-20 constitutes cruel or unusual punishment in violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Michigan Constitution.