Summary of Argument

Experience, science and this Court’s precedents all recognize that children are fundamentally different than adults. One of the most significant aspects of this difference is that children who commit criminal offenses are less culpable than adults. Roper v. Simmons, 543 US. 563, 569-70 (2005). These principles bear directly on the constitutionality of juvenile life without parole sentences. Such sentences fail to comport with the requirements of the Eighth Amendment for the reasons raised by the Petitioners and supporting amici and because the unique characteristics of youth can critically undermine defense counsel’s ability to effectively assist their teenaged clients, and the compromised attorney-client relationship contributes to an increased likelihood of unreliable sentencing outcomes that fail to reflect culpability and guilt. Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 320 (2002). For these reasons, individuals younger than age 18 at the time of the offense should not be subject to life without parole sentences.

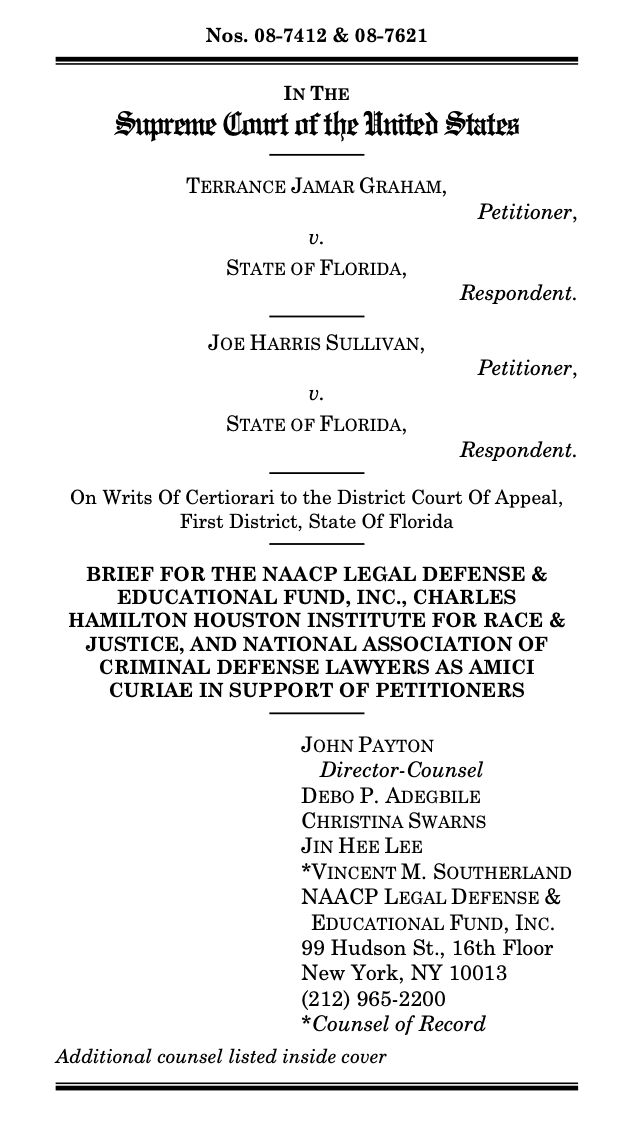

Open Amicus Brief as PDF